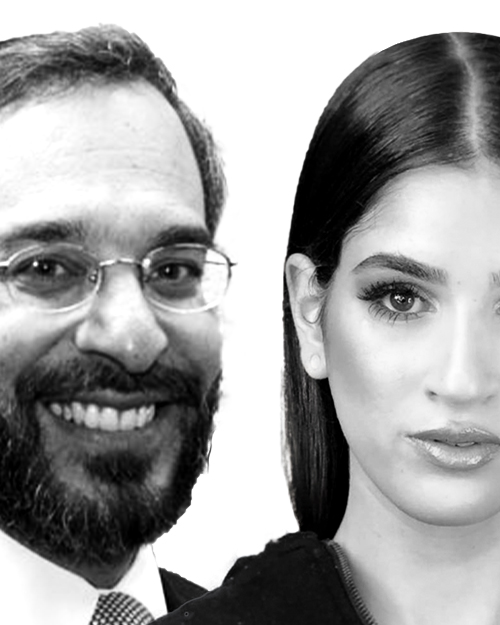

Moshe Weinberger: ‘The Jewish People are God’s shofar’

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger joins us to answer 18 questions on Jewish mysticism, including prayer and the smallness of mankind.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

In order to study Kabbala, argues Rabbi Moshe Weinberger, one must approach it with humility, holding one’s hands out in the form of a cup as though they are ready to receive.

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger has served as mashpia at Yeshiva University since 2013, and he is the founding rabbi of Congregation Aish Kodesh in Woodmere, NY.

Today, he joins us to answer eighteen questions with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy on Jewish mysticism including the smallness of man, prayer as dialogue, and his transformative introduction to the world of Kabbala.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Rabbi Moshe Weinberger, the Rabbi of Aish Kodesh and really an incredible inspirational leader for so many Jews around the world. Thank you so much for joining us here today.

RABBI MOSHE WEINBERGER. Thank you for having me.

LEVY. So, Rabbi, what is Jewish mysticism?

WEINBERGER. So first, the term that I prefer is Pnimiyut haTorah or ohr haTorah. Kabbala is something that, as the word implies, something that we received from the very beginning, even before the Torah. From the time of Adam, of Adam Harishon. Just as everything in the world exists in two forms, it has – there’s a body and there’s a soul.

The Zohar in parashat Behaalotcha calls mysticism nishmata d’Oraita, the soul of the Torah. That means that we have the laws of the Torah, we have the stories of the Torah. But just as a body would be inanimate and lifeless without a soul, Judaism and the Torah doesn’t have a life without that soul that was handed down. When God gave, when Hashem gave us the Torah, it says anochi Hashem Elokecha, I am Hashem your God. And our rabbis, our sages, Chazal teach us that anochi are the letters – contains within it the letters – ana nafshi ktavit yehavit. That God said, I have given My soul in this book. I have infused this book, the Torah, with My very soul.

So, whereas the body of Torah is mostly concerned with the question of ma, what, what is the law? What happened to Abraham? What? The soul of Torah is mostly concerned with mi. Who? Who is He? Who is the one who gave us this? How can we connect to Him on a deeper level? That’s the soul of the Torah.

It’s interesting. Everybody is familiar with the Pesach Haggada, the Passover Haggada. We begin with ma nishtana. That’s ma, what is it? How is this night different? But by the time we get to the end of the Seder, it’s echad mi yodea. Who knows? Mi, who is He?

And in the introduction to Zohar, much of it is based upon a verse in the Prophets. Se’u marom eineichem u’re’u mi bara eileh. Lift your eyes up to the heavens and see Who created all of this. That’s really the introduction to mysticism, the question of Who.

LEVY. Beautiful. It’s like we see creations in the world, but Who’s the Creator behind that creation?

WEINBERGER. To get to know the Creator, to connect to the Creator. That’s really what mysticism is all about.

LEVY. And so, how did the Rabbi connect to that? Where did – was there a moment in time when you remember connecting to this deeper form of Torah?

WEINBERGER. I remember when I was, I think at that time fourteen years old. And I lived in Israel, in Eretz Yisrael at that time with my family. And a relative of mine took me to a very, very great rebbe, to a great tzaddik. And I was just an American kid that was mostly concerned with the Yankees and reading the Mets and that’s, of course I was observant. I was raised in yeshiva. But until that time, my entire study of Torah, my connection to Judaism was the black letters on the parchment. And I was absolutely overwhelmed and transformed by the exposure to this huge Hasidic gathering and this rebbe, this rabbi. And he hadn’t yet even opened up his mouth. He hadn’t said a word. So I had this sudden feeling that there’s much more to Judaism than the written words. There’s something else going on. And it ignited within me a fire to look into that. And I began from the time I was fourteen, really, to search for something deeper.

LEVY. It’s so amazing to me that it wasn’t even what he said.

WEINBERGER. No, it’s what he didn’t say. His presence.

LEVY. The white fire around.

WEINBERGER. It was the white fire. Exactly.

LEVY. In an ideal world, would all Jews be studying this type of Torah?

WEINBERGER. The ideal world is around the corner.

We’re davening, we’re praying for it. We’re looking forward to it. I hope when we walk out of here it’s going to be upon us. Absolutely. The navi, Yeshayahu, Isaiah the prophet, the prophet said, ki kulam yedu oti. That all are going to know Me. Knowledge of God, this goes back to what I was saying. It’s the answer to the question of mi ata, who are You? We say in every blessing, Baruch ata. Every one of you says Baruch ata. Blessed are You. Who are You? So, when the prophet told us that the time will come, u’mala haaretz deia et Hashem kemayim layam mechasim, that awareness and knowledge of God will fill the world like the oceans, the waters cover the ocean bed. It means that every single Jewish man, woman, and child, and in truth, everyone in the world is going to be awakened to a new awareness of the secret of the spaces in between the letters, of the secret of God’s presence, that presence and to the extent that the human mind is capable of understanding, we will know Him. And that’s what mysticism is about.

LEVY. So what does the Rabbi think about when we say the word God or yud, kei, vav, kei or these different expressions. What is God? When the Rabbi closes his eyes and he’s praying or experiencing God in a moment, what is God?

WEINBERGER. That’s a fantastic question because it raises a theological problem of envisioning something when speaking of God. It’s a very, very big debate among the rabbis, the scholars, and so on. But my direct answer to the question of what do I think of, absolutely nothing. Now, what I mean by nothing, I don’t mean nothing the way it’s used. I mean, I think of ayin [nothing]. I think of absolutely everything, but nothing. And from that vastness that is infinite there come all kinds of images. It switches in my mind.

Sometimes it’s the ocean and I’m a drop in the ocean. Sometimes I’m a particle that’s in the sky and that I’m embraced in that reality of God’s existence. And then within five minutes, I could see, I’m being honest, you asked me, I see my father’s face. Because that’s how I connect to God for the time I was in this world. That doesn’t mean that I think that God is a body, a physical form, God forbid. But all the kindness and all the love and all the connection, I bring it down from that place of vast oceans and spacious skies and the infinity and I bring it into my father’s arms. I bring it sometimes like Rabbeinu Yonah, one of the great sages, taught us. I see myself standing at the wall in Jerusalem and feeling a light that surrounds me.

Truth be told, there were great rabbis who believe that one can imagine some sort of an image. But that’s not the most theologically sound and accepted view. But I’m sharing with you my personal thoughts.

LEVY. But I think that’s very relatable for people and especially, you know, the vastness of the ocean and to juxtapose that with the loving kindness that your father represents.

WEINBERGER. Because I feel that I need to bring it into something that I can relate to in a very, very personal way. And with all the teachings and what I’ve studied my whole life about God, but that nearness, again, not God forbid making it a physical form, that’s the Golden Calf. I’m not talking about anything like that. But the love in the eyes and the smile and the warmth, I just try to bring it into that vessel to connect.

LEVY. Beautiful. What is the purpose of the Jewish people?

WEINBERGER. In the 43rd chapter of Yeshayahu, of Isaiah, I believe it’s the 43rd chapter, I believe so. You have a couple of words. It says, Am zu yatzarti li, tehilasi yesapeiru. Some of you might pronounce it tehilati. Am zu yatzarti li, tehilasi yesapeiru. I created this nation, this people, to tell my story, to tell the story of God. We were given the tools, the wisdom, the souls. We’ve been wired to be able to tell that story. We are uniquely equipped with the ability to tell the story.

Therefore, atem eidai, you are My witnesses. We are witnesses from the beginning of time. We are witnesses to that greatness of Hashem. And Hashem wants us to bear witness, to tell the story. We tell the story through the books of Tanach of the Bible, through the teachings of Talmud, through the deepest, deepest secrets of the Zohar and other books of holiness. But our purpose in this world is to be like, you know, when you blow the shofar, the voice of the person who’s blowing, the soul of the person who’s blowing, it goes through that physical vessel. That’s called the shofar and we hear. The Jewish People are God’s shofar. Hashem exhales His being into this universe through the shofar. We’re His shofar. And we say it with words, our crying, even our suffering. Even our suffering, our loving each other, it’s God’s story. We’re the storytellers.

LEVY. So how does prayer work?

WEINBERGER. Man was created in God’s image. That’s the very beginning of the Torah. Tzelem Elokim, God’s image. And there are many opinions; what does that mean? What is God’s image? Rabbi Saadia Gaon said it means that man can control the animals or can take hold of the world and use the world for his own purposes and so on. Nachmanides says that man has the ability to change things and to create. And Sforno says that that man is the only creature that has the ability to have free choice, to choose, to to make decisions and choices. The Kabbalists say that man has a soul. The Baalei Mussar [Mussar masters], Rabbi Dessler says that man has the ability to be kind and to give. But they’re not talking about what the purpose of all of this is.

The purpose of all of this is, we say in the final prayers of Yom Kippur by Neilah, where we say: Ata hivdalta enosh meirosh, vatakireihu laamod lefanecha. Translated, you have separated man from the beginning. You, meaning God, have separated man from the beginning, vatakireihu laamod lefanecha, and You have given him the ability to stand before You, to stand in His presence. Prayer, davening, is the gift that God gave man to be able to stand in His presence where the entire world doesn’t exist, only Him.

What you do with those moments, there are many words, some of them were given to us. You could have your own. But the yesod of it is, the essence of it is that this creature that’s the image of God has been given the privilege to stand in the presence of God and to be able to speak to God as a friend, as a father, as a husband, as a wife. We see in the Bible different ways that Hashem relates to us. And it’s an opportunity to reach the deepest part of who I am, to uncover myself and to feel that I’m safe talking to my father, to my king, and pouring my heart out to Him, telling Him everything about my life and trying to find out more about His life and having this dialogue with Him. That’s what tefilla is to me.

LEVY. It’s this intimate expression of a relationship.

WEINBERGER. A conversation, a dialogue. It’s not one-sided.

LEVY. Beautiful. So what is the goal of Torah study then?

WEINBERGER. According to the Hasidic masters, and this is explained at length in Tanya and other great texts as well, the ultimate objective of Torah is that the finite human mind is actually able to connect to the infinite mind of God. When I’m studying Torah, even though I might be involved in some mundane argument that’s thousands of years old about who owns this piece of property, who owns this coat, I could be involved in something like that. But that somehow, in some way, on some level, if I enter into the into the depths of this discussion between the rabbis, and I study this text with the intention to connect my mind to the infinite mind of the Creator, and through the study of Torah, with that belief that I can accomplish this, my mind is actually sort of interfacing with the infinite mind of God. Therefore, the ultimate goal of that is to achieve a very high level of connection, of attachment to God.

Not everybody sees that as the goal of study of Torah. I’m talking about the Hasidic approach. And the Hasidic approach is that the ultimate goal of Torah is dveikut, bo sidbak – is binding oneself through the through the most exalted part of my being, which is my mind, being able to connect my mind in ways that I don’t even understand intellectually, because it’s not a matter of intellect. It’s something much deeper than intellect. It’s much more than just understanding what the Talmud is saying or understanding what the verse in the Bible is saying. It’s every moment remembering who’s the one that gave this to us and who’s teaching this to us. And therefore we have a tradition that when we begin to study, when we sit down to study, we pray for a moment, we daven for a moment that this should be an experience that transcends my understanding with the intellect.

The same way that the great rabbis said that you could paint a painting of a bird but that doesn’t mean it’s a living bird. When you read a verse, when you study something in Torah, it appears like something lifeless on a page. But the truth is that when you ascend from world to world, to a higher world and a higher world, it’s a living organism. That verse, that teaching is something that’s alive. And you’re connecting to it.

LEVY. Your eyes even come alive when you say it. And then unfortunately, sometimes I see in classrooms, you know, it becomes a rote process that people are not seeing as animated as what you describe. Is there any advice to give educators, to give parents, or to give students for when they learn Torah to to have this experience of dveikut, of that cleaving that you described?

WEINBERGER. I think it goes back to what I said a moment ago. We already have received the tradition that it’s, we see already in the Talmud that it was, that there were prayers that were established when you’re entering into the study hall of the beit midrash. The purpose of those prayers was not just to be successful. If you look at them, you’ll see it’s not just a matter of being successful and understanding what you’re learning. It’s being able to experience what you’re learning.

When God gave us the Torah at Har Sinai, at Mount Sinai, there were a lot of special effects. There’s thunder and lightning and we’re told that God opened up the seven firmaments of the sky. Like, what’s all the drama? Because [when] studying Torah, parents and teachers need to expose the kids not just to the words that were spoken on Har Sinai but to the thunder and lightning of Har Sinai. To the special effects of Har Sinai. And the way to do that is children especially are able to pick up very quickly when the teacher, whether it’s the the mora or the rebbe, the woman who’s teaching or the man who’s teaching, or the father or mother are talking, children pick up very quickly whether my parents are just reciting the words that were given to us on Har Sinai or they’re giving me the fire of Har Sinai. They’re giving me the thunder and the lightning of Har Sinai.

So, when we were growing up, when my kids were growing up in the house, so Shabbos [Shabbat] was a dance at the Shabbos table. Saying over a piece of Torah wasn’t about making just pasuk aleph and pasuk bet, the first verse and the second verse, work out. It was, what is it that, what does God want us to experience through this? What are we supposed to feel through this?

So, when the Baal Shem Tov’s greatest disciple, the Mezritcher Maggid, first came to him, the Mezritcher Maggid was a great master of Torah. And of the revealed Torah and the hidden Torah. And when he came to the Baal Shem Tov, the Baal Shem Tov was studying a certain piece of the Zohar and he asked the Mezritcher Maggid, he showed him this piece of the Zohar and to please explain. And the Mezritcher Maggid looked it over for a few minutes, he was a genius and a great mystic, and he offered a profound explanation. And the Baal Shem Tov was not impressed. Even though certainly it was unbelievable what he said. And then the Baal Shem Tov began to expound on that piece of the Zohar. And the Mezritcher Maggid described what that – he described it. He said that the room became entirely dark and the Baal Shem Tov was engulfed in flames, and the entire room was engulfed in flames. And I can’t discuss what happened, what that was. And what that means is that the Baal Shem Tov said, when you learn Torah, we’re going to learn this piece of Zohar, but we’re going to go there. We’re not just going to talk about it. I’m taking you there. We have to take our kids, our students to the Torah, to that experience, to that joy, to the dancing, to the singing, to the thunder, the fire, the lightning. There’s no other way.

LEVY. Beautiful. You talked about the mora and the rebbe, mother and father. In Kabbala, Jewish mysticism, there are discussions of the male and the female. Are men and women different or the same in that tradition?

WEINBERGER. So, here in America, we have a new administration, so it’s safe to talk about this. And yes, male and female are of course different. It says that at the very beginning of creation, when Hashem created man, zachar u’nekeivah bara otam. Hashem created male and female. And the difference, however, is you can get caught up in all kinds of arguments about gender when you’re talking about the surface of things.

But Pnimiyut HaTorah, the inner light of Torah, of course, addresses the deeper significance of two types of energy. There’s male energy and there’s female energy. There’s the sun, there’s the moon. There’s the energy that is of giving, and there’s the unbelievable koach, the energy of being able to absorb and to receive. These are two diametrically different levels of creation, male and female. How they’re embodied in this world, that’s the issue of zachar u’nekeivah, male and female.

But it was taught to us by the Kabbalists, going back to the Torah itself in many places in the Torah. So for instance, the right side and loving kindness is a male [characteristic]. Chesed is a male characteristic. The left side, which is gevura, which is strength, is a female characteristic.

So many people would say, I don’t understand that. My mother is the most loving person in my life, and my father is the strongest person in my life, traditionally, conventionally, everybody should forgive me. But these definitions and the way Kabbala treats these two worlds of zachar u’nekeiva transcend all of our silly interpretations of what does love mean and what does strength mean. When one enters into Pnimiyut HaTorah, into the inner world of Torah, you begin to see what is really a male and what is a female. And neither one has anything to be ashamed of.

LEVY. Beautiful. What is the greatest obstacle to living a more spiritual life? You hear from so many different people, you field thousands of questions. Is there a theme that comes to the surface that feels like an obstacle?

WEINBERGER. I would say there’s one word in Hebrew that I would use to, I think, to sum up what I’ve encountered over the past forty-five years of trying to reach out to people. Jews and, many times in my life, non-Jews as well.

The one word I think would best express it would be katnus. Katnut. Katnut means smallness. A smallness in an emotional, spiritual sense, not necessarily intellectual – people are more educated than ever before. But when we look into the Zohar again, we see that the Zohar talks about a song that has different parts or different levels of song. There’s a shir pashut, a shir kaful, a shir meshulash, and a shir meruba. That means like a single-chord song, there’s a double, triple, four [-chord song].

And Rabbi Kook, Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaKohen Kook, spoke about the ultimate song, which is: Shir hashirim asher l’Shlomo, the Song of Songs. So what does that mean? It means katnut is when a person’s song, he has one chord, it’s all about himself. It’s all about himself, it’s a selfie. It’s about himself. It’s about his little world. Now he might be a brilliant person, or she might be a genius, but it’s about what can I do for myself? What can I – how can I be satisfied? You know? It’s indulging in the self. A baby, when a baby’s born, the baby only thinks of himself or herself and I’m hungry, I’m tired.

Slowly the song, hopefully the song develops into something more complex and something more beautiful, where the child begins to recognize that this lady, this man, they’re good to me. I love them. I don’t know what love means, but I know that I’m connected to them. That’s already a song that’s becoming more complex, it has two notes.

And this grows, so a person is able to feel a love for his people. Rabbi Kook speaks about this in Orot Hakodesh. A love for the Jewish people. Then ultimately even grow to a sense of love for all of mankind, the entire world, and a love for all of creation. And at the top of all of that is Shir Hashirim, is the love of God.

So, what Rabbi Kook and the way he explains the Zohar is that if you’re stuck in smallness, if your whole life is about selfies and scrolling and that’s your whole life, is what makes me laugh, what makes me cry, what makes me feel good, I’m not really able to to compose that type of music. And if I can’t compose more complex and more elegant music, beautiful music, I’m not getting to God. I’m not really getting to God.

So, we see for instance that when we begin davening according to the Arizal, when we begin praying in the morning, our prayers we should begin by saying, Hareini mekabel alai mitzvat asei shel ve’ahavta le’reacha kamocha. I accept upon myself the mitzvah to love other Jews. To love another person like myself. Ve’ahavta le’reacha, to love my friend like myself. Why? I’m supposed to be – this is spiritual, I’m supposed to be talking to God. This is the most spiritual time, the time of prayer. Why am I talking about loving my parents and my sister, my brother, my community, mankind. Why not just get spiritual right away?

Spirituality is a ladder. And in order to climb that ladder, the first rung is getting out of your tiny, miserable little world even though you might have a billion people on your web or I don’t know what it’s called.

LEVY. On social media.

WEINBERGER. On your social media thing, you might have, you might have half the world. You could still be a pathetically tiny person. Therefore, we begin by climbing out of ourselves.

Rabbi Kook explains how Rabbi Akiva was a lonely shepherd that was wrapped up in his own life. According to the Talmud, he detested the sages when he was a young man. But then the Talmud describes to us in Yevamot that Rabbi Akiva fell in love with Rachel bat Kalba Savua. His heart began to open up to something besides himself. And from there, he was the one that taught ve’ahavta le’reacha kamocha zeh klal gadol baTorah, the great principle of Torah is loving other people. And then from there, he went to war to fight for the entire nation against the Romans and so on. And then ultimately, he was burned alive by the Romans. And the words that were on his lips were ve’ahavta et Hashem Elokecha, Shema Yisrael – to love God with all your heart and all your soul. That’s a spiritual person.

LEVY. Wow.

WEINBERGER. Not someone that just talks about God. A person who knows how to talk to his parents, knows how to talk to your sister, your brother, knows how to talk to another human being in a dignified, loving way. That makes you into somebody who’s beyond the smallness of your physical, emotional, intellectual, selfish needs. It takes you to a world beyond yourself. When you get really beyond yourself then you’re at a place of everythingness. And everythingness is ein sof, is the infinite one Himself, is God.

LEVY. Really, really beautiful. And I think it expresses the truth of Judaism is if I give to others, then I can go beyond myself.

WEINBERGER. That’s spirituality.

LEVY. And ultimately that leads me to God Himself.

WEINBERGER. Right. Giving a call to your grandmother when she could use it is very spiritual. It’s a very spiritual thing.

LEVY. I think it’s very important that someone of your stature shares that for people to hear because unfortunately, sometimes we get distracted with certain rituals, which of course are critically important, but so is that conversation to your grandmother.

WEINBERGER. Absolutely.

LEVY. Why did God create the world?

WEINBERGER. Okay, the creation of the world and God’s point in creating the world is of course, this has been discussed in great detail by our masters, our teachers. So we have the Ramchal and we have the Arizal and many, many great teachers that [say that] God is the most absolute, altruistic being. We can’t understand who He is, but we know that His entire being is to give and to love. And the greatest act of love is to be able to create human beings, to create those who are able to delight in experiencing that oneg, that pleasure of being able to have a transcendent relationship with the one who created them.

Ultimately, the Hasidic masters, again, going back primarily to the author of Tanya, but all the righteous tzaddikim speak about this. Nitavah Hakadosh Baruch Hu lihiyot lo dirah b’tachtonim. Hashem desired. Now desire is not something that we can understand. We don’t understand God’s infinite mind, but Hashem desired to have a dwelling place in this world. Therefore, the point of creation is something that was actually very well told in a story that was shared by one of our friends, our mutual friends, from the Frierdiker Rebbe. When the Frierdiker Rebbe was trying to help one of one of his messengers, the Frierdiker Lubavitcher Rebbe was trying to instruct one of his messengers to go to some some outpost where there were a few Jews and to bring Judaism to that outpost and to leave his comfortable study hall, and his familiar family surroundings in Brooklyn, and to go out somewhere to bring Torah. So that person really didn’t want to go. He was satisfied staying in the study hall. And the Rebbe held his finger up and he said, and he was showing his finger going down like this. He said, the soul doesn’t want to come down. The soul doesn’t want to be in this world. The soul doesn’t want creation. Because why? Because in that world with God, how is this varm and lichtik. Everything is warm and sunny and good. I don’t want to go out to that place. I don’t want there to be a world. But Hashem tells the soul, you have to go down. But the soul says, but down below is kalt and finster. In Yiddish it means it’s cold and it’s dark. I don’t want to be in a cold and dark world. And the Rebbe is going further down with this figure and he tells the rabbi. In Yiddish he tells him, machten dort to make over there, down in that physical world to make it warm and bright in that world.

And the rabbi said that when he went, he was in that community for over fifty years. And many times it was very challenging for him to stay there. He would always close his eyes to see that creation that took place, how creation took place. That point of creation is to come from a warm and illuminated existence, to come into the coldest, darkest existence and to give it the greatest pleasure of all, which is to be illuminated by that light and to be warmed by that light of the Creator. That’s creation.

LEVY. Amazing. Does free will exist? And what is it if it does?

WEINBERGER. Okay, that’s a twenty-four hour, seven-day week, seven-day conversation. Rebbe Noson [Rabbi Natan] from Breslov once asked his teacher, Rebbe Nachman, what is the mystery, the secret of free will? Because after all, God knows what we’re going to do. So what is – that is the ultimate question of Judaism. How do we reconcile our free will with God’s foreknowledge? Maimonides, the Raavad, everybody, this is the topic, the hot topic, by the Middle Ages and before and after.

So Rebbe Noson asked Rebbe Nachman. So what is this? What’s the secret, Rebbe? What’s the secret? What’s this? No, he wanted to know the deepest kabbalistic mystical teaching. And he was capable of grasping it. And Rebbe Nachman was quiet for quite a few minutes. Now, when Rebbe Nachman would think for let’s say ten minutes, that’s like regular people like us spending an entire lifetime, at least [with regard to] thinking. So Rebbe Nachman is thinking for like ten minutes. And then he looked at Rebbe Noson, his student, and he said, if you want to do something, you do it. And if you don’t want to, then don’t do it. That’s the secret of free choice. That’s what Rebbe Noson said he heard from his rebbe.

So, now you have to understand that when Rebbe Nachman said that, he went through all of the philosophy, all of the Kabbala, everything he went through. And he said, if you want to do it, [do it], if you don’t want to, don’t do it. Now, let me just explain for a minute. Therefore, there is free choice. However, free choice, the free choice that Rebbe Nachman was talking about, that we feel that we can exercise. It’s overrated. There are limitations to it, but I want to explain. Again, I can’t in a minute, but mashehu, a drop, a drop.

There’s a book of the teachings of the Arizal called Arba Meah Shekel Kesef. Arba Meah Shekel Kesef, Rebbe Chaim Vital, one of the great masters of Kabbala. And he basically says over there that there is a level of existence that’s called atzilut that transcends its eternal level of closeness to God, of His world. In that reality of God Himself, everything is known. In that reality, there’s no reward, there’s no punishment. There’s no such thing as good, evil, as Haman, as Mordechai, as there’s no – it’s something we can’t, the human mind can never, ever reach, can never touch. Even the greatest, even Moshe Rabbeinu, even Moses didn’t understand.

But that world that’s called atzilut, the Arizal taught, in other words, God’s knowledge is not machria, it does not force you and I in this lower level of existence in assiah, in the lowest realm of creation. It does not force you or I to make this choice or that choice. However, God has a plan. And God, there are times when all of a sudden, the lights sort of go out, like for instance when the Red Sea was parting. So people were scared, Egyptians are chasing us, we don’t know what to do, and everybody’s crying. What’s going to be? So Moses, Moshe is praying, was davening. And Hashem says, no be quiet. Ma titzaku, what are you davening? What, am I davening? What else is there to do? What do you do when you’re in trouble?

So that was a moment of something else happening. There was a moment of atzilus. In other words, God makes cameo appearances from that level of atzilus of His foreknowledge when the world is messing things up and everything could go off track with our choices, like the Egyptian choices, whatever. Things can go off, can be derailed. And then there is a sudden explosion from that higher world. Atika Kadisha, suddenly the ancient one that transcends all creation, and He has His knowledge and He has His plan of what must be. All of a sudden, everything just stands back and the ocean splits and we are just taken along for the ride. So, does that happen to me and you in our individual lives? There is such a thing, but we don’t know.

And our job is not to try to predict or to figure it out. Our job is to do what Rebbe Nachman said. Try to do the best that you could do and believe that that choice is within your hands. Are there some things that are beyond the level of choice? Even sometimes, is [it] possible, sin itself? Yes. The Baal Shem Tov has a teaching that in the word sin, chet, chet, tet, alef. The alef is silent. Means alef stands for God because he’s Ado-shem, and Alufo shel olam, the Master of the Universe, the alef. That means even when man sins, there’s some great divine plan that’s part of it. There’s something there.

Was it a matter of your choice? Are there consequences? Yes, but we don’t understand. Only God knows the life that He brought you into. So He set you up in a certain life where it could be that you were almost doomed to fall in that way. There are things like that. But our job is, that’s not our cheshbon, that’s not our job to calculate. Our responsibility is to do the best that we can. When this world is finished, when it comes time for the end, then God will reveal to us that there were certain things that were not a matter of our choice. There was a light that came from atzilus and higher spheres.

LEVY. You talk about, when it comes to the end, when God will reveal to us, we know that as the time of Mashiach. I found it very moving when you described what you imagine when I say the word God. What do you imagine when I say the word Mashiach?

WEINBERGER. So, Mashiach, of course, as a child growing up, it meant that Mommy and Daddy are not going to have to be in Auschwitz and Mauthausen anymore. It meant in our context now that there won’t be any more an October 7th, it won’t happen again. It meant that everybody’s, all the soldiers will come back to life and all the ones who are injured, their limbs and organs are going to appear and life [will] be good, and now as a kid it meant that I’d have a fiberglass backboard to play basketball on whenever I wanted, you know, not a wooden cheap thing or on somebody’s garage, you know, fiberglass backboard in a polished beautiful floor to play on. That was Mashiach. Anything that it can’t get better than that, that was Mashiach.

When you look into the deeper teachings of Torah, you understand that, of course, life will be good. And we know that wars will end and there’ll be peace in the world. All that the prophets have promised through God will take place, 100%. But the truth of the matter is, the same way we’re taught that when a person leaves this world there are a number of questions he’s asked, there’s sort of an interview at the end. And that interview at the end is, I mean, how those could be a podcast, but there’s an interview at the end. And the interview at the end, the big question is, tzipita liyeshua? Did you long for salvation? That question, did you long for salvation, it didn’t mean for the, just for the basketball court, or even for the peace, or even for the people coming back to life. It means, did you long, did you long throughout all the difficulties of your life, were you a person that was filled with hope?

Mashiach, the Me’or Einayim teaches us, other tzadikim, other great, righteous masters taught us that Mashiach exists in the world. Mashiach exists even within us. That soul, that reality of Moshiach since the beginning of time. To be able to believe in the ultimate purpose of creation, that it’s good, and that God is good, that there’s a reason for all of this. And [it is] all for something so great it’s beyond anything we could imagine. Anything great that was promised us, infinitely greater. And that hope that I had gave me life and light through the most difficult times of my life. That’s called believing in Mashiach.

So what will it be when Mashiach comes? Going back to the beginning of our conversation, it will be the answer to all my prayers. Opening my eyes and seeing that I’m standing in His presence. Again, it’s not a physical thing, but it’s that absolute clarity. That’s when Mashiach is there for. You see that the word Mashiach is brought down from the sefarim [books], the old ones, that Mashiach is a lashon [language] of lasiach, lasuach, which means a conversation. It means to be able to come to that place and that time [with] that awareness of who God is. And also [to be] looking at everybody in the world to be able to see who that person really is. Not all the masks and all the masquerades, but to see that person’s soul, who that person really is. That’s what Mashiach is.

And even now we can work on revealing that Mashiach point within ourselves. When we study the inner teachings of Torah, we’re connecting to Torat HaMashiach, to the light of Mashiach tzidkeinu. Mashiach is a person and he’s going to come and we’re going to have the king and there’s going to be redemption. But it’s a process. And that process depends and that process is fueled by our living as people of hope despite all the things that we’ve gone through, each person in his life, continuous, continuing tzipita liyeshua, to believe and to hope for salvation, for the good ending. And while I’m alive in this difficult world that I’m in of free choice and darkness and light and so on, to believe that at this very, very moment, by my making the right choice I’m contributing, I’m bringing about on some level the revelation of that light of Mashiach that will ultimately be revealed with our full redemption.

LEVY. Is the State of Israel part of that process towards the final redemption?

WEINBERGER. It’s also a matter of great controversy. How do we define the political State of Israel? And in my lifetime, I’ve gone through different periods where I felt more connected to different opinions.

There are those who would like to define it as being aschalta d’geula, the beginning of redemption, or the beginning of the unfolding of redemption. There are those who say that no, we can’t really speak in such terms. We’re not able, we’re not on such a level to define this. So the way that I see that is the State of Israel is as an imperfect, unbelievable smile from the Creator of the world after that time, at the end of history, which I see the Holocaust as the end, as the end of that darkness and what we’re going through right now as a people, what’s happening to us now, the resurgence of that antisemitism and so on. These are afterquakes of – I believe the Holocaust never ended. I believe that it will end. But that smile, in 1948, I’ve come to believe that was a smile from the Creator.

To say that this is already redemption itself would be ludicrous. There are so many difficulties, there are so many challenges yet and there’s unfortunately so much fighting going on among Jews in Israel. And we can’t speak of it being the beginning of redemption, but is it the smile, is it the wink or the murmurings of the end of our exile and the awakening of Mashiach? I believe so.

LEVY. So what is the greatest challenge facing the world today? You talked about many of these darkness issues. Is there something that stands out?

WEINBERGER. Well, I think that I tried to address that before when I was describing katnut.

And then I see that, I see the shrinking of man as being the greatest challenge. And the consequence of that shrinkage with all of the expansiveness with technology and so on, but the greatest challenge I see is being small and selfish and preoccupied with oneself, with one’s own turf, with one’s own country, with one’s own place, one’s own life. I see that as being the greatest challenge on a very, very more basic level.

Something that I spend a lot of time talking with with the fathers and the young men in particular in our shul, in our community, is the immorality of the world that we’re living in right now, the depravity, the immorality when it comes to holiness, a lack of a feeling now, a lack of holiness, of basic refinement and civility and respect for privacy.

But all this comes from again, a certain katnut, a smallness. I think I see this as the greatest challenge. The repercussions of that, it all comes out and then a loss of identity, a loss of a sense of purpose and meaning. People are looking for meaning, they’re looking for purpose. We would not have had such a conversation twenty, ten, five years ago.

LEVY. Yeah.

WEINBERGER. The world is ready for it now because people feel the katnut, the smallness. They’re looking for something bigger, they’re looking for something meaningful.

So, like Rabbi Kook said, that on the one hand, this is a very, very small generation. On the other hand, there’s never been a greater generation. There’s such an openness, there’s such an honest desire to find something bigger because I think that people are just tired of the emptiness. So it’s this emptiness and smallness that is characterized by immorality and getting lost trying to find some gratification in physical things where those who are most honest are already able to to surrender and say, I haven’t gained that satisfaction and that joy that I’m looking for.

LEVY. Has modernity precipitated any of this in the last few decades? What has modernity done to Jewish mysticism? Has it changed it in any way?

WEINBERGER. Rabbi Kook said that as the world becomes more sophisticated, we have to be careful. We have to be very careful because we’re not living anymore in little shtetlach, little villages with unsophisticated peasants. The world has become more sophisticated. Therefore, there is a benefit to the fact that modernity opened up the gates of the ghetto and exposed the world to much bigger and broader ideas, more sophisticated ideas. Therefore, what’s crucial is that we now expose our own children, our students, and ourselves to much more sophisticated, greater, and broader ideals and ideas of our Judaism and of self-awareness.

So modernity has brought tearing down those walls of the ghetto, so to speak, and the whole process of modernization has taken man beyond, has tried to take man beyond the small confines of that katnut that we’ve been talking about.

LEVY. Yeah.

WEINBERGER. There are some that all they’re looking for is the next level of an iPhone. That’s what they find most gratifying. But on a deeper level, the sophistication, the broadness, the expansiveness that comes with modernity has made it possible for us to have this conversation.

LEVY. And to share with the world.

WEINBERGER. And to share with the world. My parents and grandparents would not even have been…But it brings danger. Of course there’s tremendous dangers that come with that because it’s an exposure to a lot of stuff that’s not healthy. But the underlying essence of it is expansiveness.

LEVY. Amazing.

WEINBERGER. Which is great.

LEVY. Is Jewish mysticism different to other forms of mysticism? And if so, what is the unique difference? What’s special about Chasidut, Kabbala, Pnimiyut HaTorah in this sense?

WEINBERGER. Okay. My dear friend, I want to tell you something. From the time that I first became interested in studying these things, I was tempted to dabble in the mysticism that is out there in the world outside of Judaism. And I’m very grateful to the Creator of the world that an angel was sent to me, not from heaven, but on earth, who saw me once with a book by a very famous, non-observant student of Kabbala. And they had a long conversation with me and I accepted upon myself many, many years ago not to taste any of the fruits outside of the Tree of Life. The Tree of Knowledge caused enough damage, [the Tree] of good and evil caused enough damage at the beginning of time. Therefore, even though unfortunately there are certain things that I remember from when I was young that I did read, and I’ve been trying to delete all of them for so many years. Unfortunately, I do have some knowledge from that early time.

But it goes back to what I said before. There are mystical teachings. There are people who are trying to find the truth, and I respect people who are looking for something bigger. But they don’t have the Shaar HaKavanot. What I mean is they don’t put on tefillin, they don’t put on tzitzit. They don’t study the Torah that was given at Har Sinai. They don’t blow the shofar, they don’t sit in the sukka. They have good intentions. But intentions, intentions. Shaar HaKavanot means that Jewish mysticism is what I said about the Baal Shem Tov and the Mezritcher Maggid. Jewish mysticism is not about studying something or even being in a state. Jewish mysticism is about going there, about being there. It’s not seeing a painting of a bird but a living, flying bird. Only in our world of Kabbala is there such a thing. And I wanted to be with the Etz HaChaim, the Tree of Life, not with the Tree of Knowledge, of good and evil.

LEVY. So does one need to be religious to study this thought?

WEINBERGER. One needs to be humble to study this. Even if someone is not religious and he humbly puts on proper head covering, if it’s a male, right? And he humbly does not watch this on a computer on Shabbos, on the Sabbath. And he understands that we’re not talking here about a body of knowledge, but an experience of God. And one approaches that with great humility, he doesn’t necessarily have to be there yet religiously, he might not be Orthodox, but he’s humble.

Kabbala means to receive. One of the most beautiful things is that when you bless a Sefardi Jew, they hold their hands as a cup to receive. It’s beautiful. We Ashkenazim, we picked up some European arrogance. They hold out their hands as a cup. If you want to study these teachings, you have to hold your hands out. Holding your hands out like this means to humbly acknowledge something that’s higher than you, you want access to a certain reality. You’re asking for entrance into a certain world. You’re not asking to take a book out of a library. If you’re asking for entrance into a certain world, it has to be with humility. Does that mean you have to be fully observant? There are those who have written a number of conditions for being able to study these things, but in our times the main prerequisite is humility and a belief that there’s something greater than you, and you’re trying to enter into that and gain entrance into that secret of something much bigger than yourself.

LEVY. Can it be dangerous?

WEINBERGER. It could absolutely be dangerous. When a person studies these things without the hands held out, then it could become a matter of pure intellect. And as a matter of pure intellect, it could be unbelievably confusing. And not only could it be confusing, it could cause a person to get lost in the opposite, in arrogance and haughtiness, and we had false messiahs throughout time. And there are big false messiahs and then there are little false messiahs, little meshichelech, little meshichelech. When you think that you understand and you don’t understand, because without humility there’s no understanding.

When you asked me, what do I think of when I think of God? I said nothing. But I said it means everything. But it means you’re being able to dissolve as a nothing into that everything. It’s dangerous when you think that you’re the ocean, when you think you’re the sky, you could begin to look at yourself in a very, very inflated way and look at other people in a very deflated way. There are many other dangers: theological, philosophical, emotional, and many people have suffered from studying these things at the wrong time in the wrong way and without their hands, without humility.

LEVY. So, you’re an incredible teacher and rebbe to many. And you’re also a human being. And to many of us, we see you as this great rebbe, but I’ve been blessed in our conversations to see at least how human you see yourself. And that can be expressed through relationships. And mysticism, as you explained before, is in that conversation with the grandmother, is in the day-to-day. Is there anything personal that you can share of how the study of these teachings has influenced relationships or even a relationship in your life?

WEINBERGER. That’s a terrific question. Here’s why I found that it was very, very important for me to continue on with my studies of Kabbala into the world of Chasidut. Because Chasidut is all about earthiness and relationships. And I found it to be unbelievably helpful in my way of looking at my children in a lichtige way, in an illuminated way of trying to see them from the perspective of who they are as opposed to how they sometimes act. I wouldn’t, I don’t think I would have gotten that just by studying, I mean, other people do, but I don’t think I would have gotten that by just studying Kabbala or what’s called mysticism. I don’t think I would have gotten that.

But by combining Kabbala and then continuing on with the study of Chasidut, where Chasidut takes you down, as we said, that God wants to dwell in this world. And Chasidut takes these very, very, very great and deep teachings and brings them into the simplest teachings of how to connect to other people.

The Baal Shem Tov was a man of the people. He loved people. He went out to the people. You know, there’s a famous story about Rabbi Levi Yitzchak from Berditchev that people were all upset. They saw that this guy, Yankel, he left the shul, davening wasn’t over, he left shul because he wanted to get an early start to the day and he was oiling his wagon, the wheels of his wagon, the horses, he was oiling the wheels with his tefillin on, he was. And people looked out the window and they were shocked and they wanted the Rebbe to run out and to [talk to] him. And the Rebbe, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, went out there and he looked at him, and he said, Yankel, even when you’re oiling the wheels of your wagon, you can’t separate yourself from the Creator. Wow. Wow. That helped me a lot. I work on this all the time. It changed me from a pessimistic person into a very optimistic person. I am filled with optimism. Not only in how I look at the future and how I look at each person, I’m filled with such hope and such optimism because I got that from the Baal Shem Tov. I didn’t get that from the study of Kabbala.

Kabbala is a complicated geometrical, mathematical world. But being out there with the wagon driver, that’s the Baal Shem Tov. That’s a beautiful world.

LEVY. Beautiful. So just to end, you’ve shared these incredible ideas through these theological and practical questions. I’d like to ask you just to share an idea. Is there any short thought, an inspirational teaching from Chasidut, from Kabbala that you can share with us?

LEVY. Sure, a couple million. I’ll tell you. So I’ll just share with you something I was thinking about last week, the whole week, because last week was Purim. So, it was on my mind a lot.

There’s a teaching that says, Vatosef Esther vatidaber lifnei hamelech, Esther realized that in order to carry out this plan to undo the final solution of Haman, she would have to speak to the king about some other things and to continue on with some requests and so on. So it says, vatosef Esther, that Esther added, vatidaber lifnei hamelech, and she pleaded before the king.

Now, everybody knows that when it says hamelech, the king, in the Book of Esther, it’s a hint to the King of all Kings. So one of the great teachers taught, vatosef Esther means when you feel in your life that there’s more and more Esther. Esther means hester panim, when you feel lost, you feel that God is so hidden from you, you feel such darkness in your life, something horrible has happened to you. Vatosef Esther. Here you hear another story about a hostage that is dead or something. Vatosef Esther, there’s more Esther in your life. It says Vatosef Esther vatidaber lifnei hamelech, there’s only one thing you could do. Speak to the King of all Kings. Pour your heart out, vatidaber lifnei hamelech. Speak to the King of all Kings. Vatosef Esther, when there’s more darkness in your life, don’t run away from God. Vatidaber lifnei hamelech, talk back to Him.

LEVY. Beautiful. Well, Rebbe, I want to be honest that this entire conversation I’ve wanted to sit like this because it’s just felt like a blessing. It’s interesting, the words you’ve said have actually come to life because there’s been a revelation. It’s been like a thunder and lightning show, the passion that you’ve shared. And it’s because you mamash live it. And it’s such an incredible thing to be able to see firsthand and to be able to share with the world. And we just give you a bracha [blessing] back that you’re able ad meah ve’esrim [until 120] and beyond to just share your incredible passion and fire for Torah. Not just the white fire but the black fire. And these experiences that you’ve been through, we can all really get a sense of dveikut to Hashem through his incredible shlichut of yourself.

WEINBERGER. Amen, amen, all of us together in good health.

LEVY. Amen. Thank you, Rebbe. Thank you so much.

WEINBERGER. Shkoyach.

LEVY. Thank you.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Dr. Ora Wiskind: How do you Read a Mystical Text?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Dr. Ora Wiskind, professor and author, to discuss her life journey, both as a Jew and as an academic, and her attitude towards mysticism.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Debbie Stone: Can Prayer Be Taught?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Dr. Debbie Stone, an educator of young people, about how she teaches prayer.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

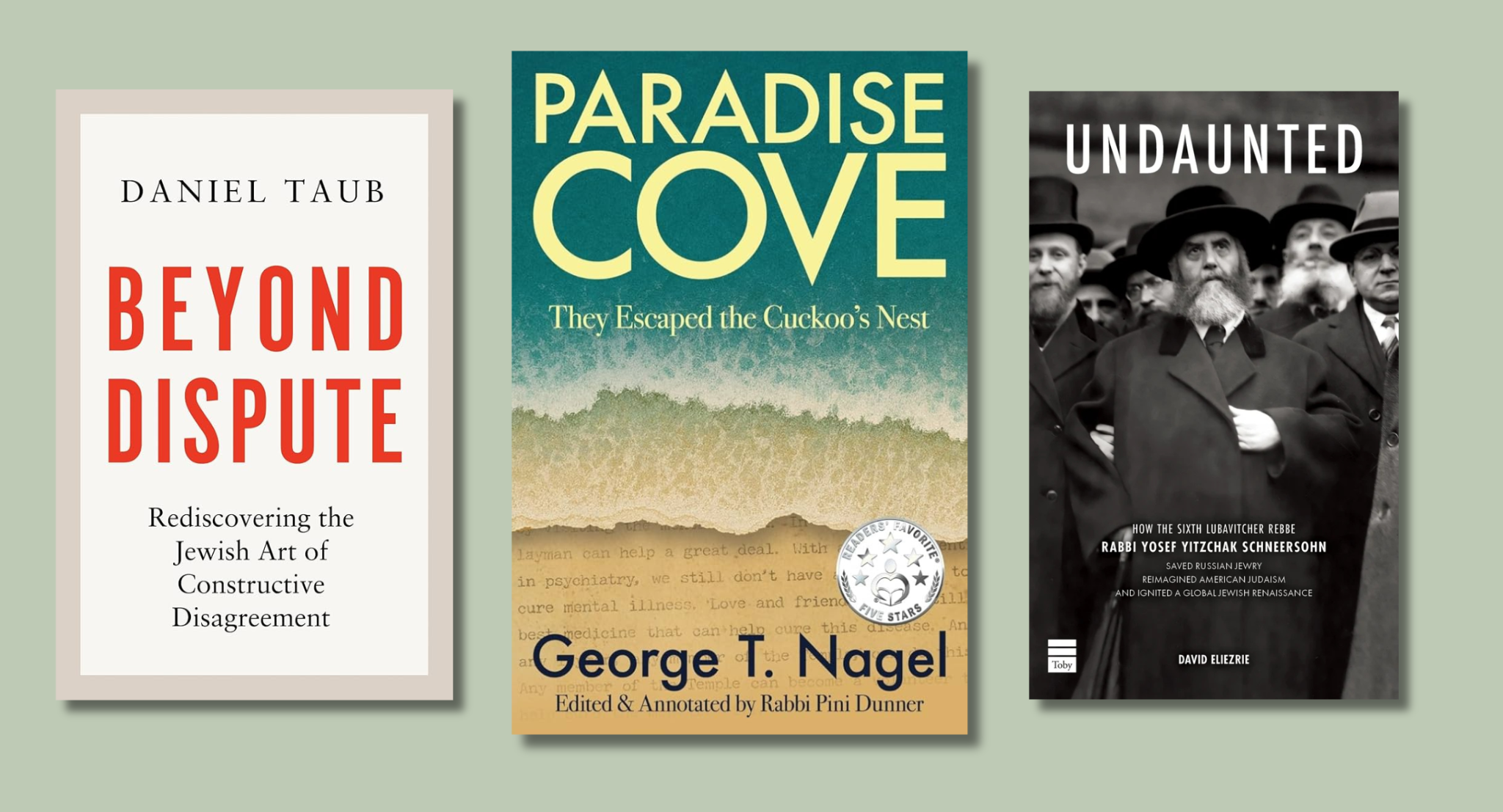

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

5 Lessons from the Parsha Where Moshe Disappears

Parshat Tetzaveh forces a question that modern culture struggles to answer: Can true influence require a willingness to be forgotten?

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

Rav Tzadok of Lublin on History and Halacha

Rav Tzadok held fascinating views on the history of rabbinic Judaism, but his writings are often cryptic and challenging to understand. Here’s…

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.