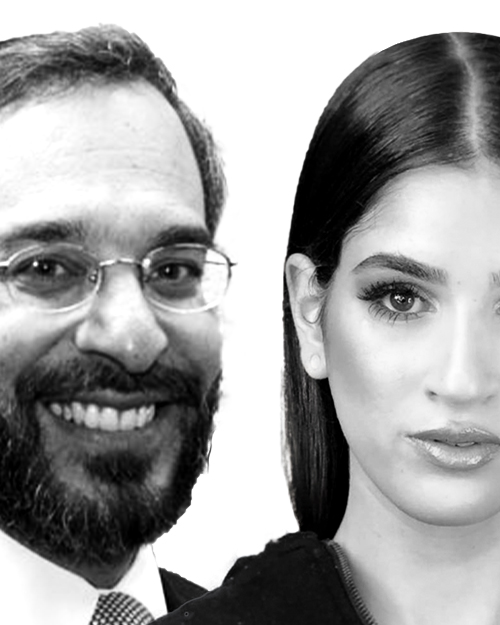

Joey Rosenfeld: ‘All Jews are by definition mystics’

Rav Joey Rosenfeld’s entryway into mystical thought began with the writings of Franz Kafka and Albert Camus.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld’s entryway into mystical thought began with the writings of Franz Kafka and Albert Camus. Discussing Jewish mysticism with Rabbi Joey is not just a conversation about ancient texts and ideas, but it is a journey into the soul, wherein he describes how mystical principles can transform relationships, heal trauma, and guide us in a modern world.

Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld is a practicing psychotherapist in the field of addiction, focusing on the interface between philosophy, spirituality, and psychology. He regularly gives classes on Jewish philosophy, Kabbala, and the inner workings of the human soul.

Here, he sits down to discuss eighteen questions on Jewish mysticism with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy including the various dimensions of redemption and the paradoxical nature of God.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld, it’s such a privilege and pleasure to be sitting with you here in the heart of Jerusalem. And you’re an incredible mystic, you’re a psychotherapist, an amazing teacher, and now a Share scholar. I can’t believe our first conversation is going to be recorded after all these times that we’ve been connecting together. So thank you so much for joining us.

RABBI JOEY ROSENFELD. Thank you. It’s a tremendous opportunity to sit here with you finally and to begin the process of sharing.

LEVY. Amen. It will never end.

ROSENFELD. Amen.

LEVY. So tell us, what is Jewish mysticism?

ROSENFELD. Al regel achat, which is a real way, on one leg, to try and approach the subject of Jewish mysticism with a definition, would be the basic awareness that there is more going on beneath the surface than that which meets the eye. Mysticism propels the individual to gaze deeper than that which they see with their naked eye.

LEVY. So how were you introduced, sort of under the bonnet, below where the naked eye can see, how were you introduced to Jewish mysticism?

ROSENFELD. Part of it is conditioning in the sense that as a child of Holocaust survivors and growing up in a Modern Orthodox healthy household, I became fundamentally aware of a split between the external functioning of Judaism and the underlying trauma that rests underneath upon which the functioning is built.

And so I became very aware quickly that there was an unrevealed aspect of experience that was giving birth and allowing the revealed part of experience to function properly. And that’s when I became aware that there was really a depth beneath the surface that needed examination.

LEVY. So specifically in the conditioning, there wasn’t a specific catalyst that sort of brought you into this? Was there a moment?

ROSENFELD. There was a moment. When I came to Eretz Yisrael and I learned in Or Yerushalayim in Moshav Beit Meir, my father sent me with books of Kafka, Camus, and other existential authors. And he said, this is what I read in my first year in Israel and I think you should be exposed to it as well. And once I began reading those texts, I began to think about different ways of relating to the world that I lived in. But it was only until after my studies in Israel that I began really learning the teachings of the Maharal, which was the opening for me.

LEVY. Interesting. And Kafka and Camus are not the obvious choice. If you were inviting someone else on this journey, where should they start?

ROSENFELD. When it comes to understanding Pnimiyut HaTorah, Jewish mysticism, I don’t necessarily think I would recommend Kafka and Camus. But the idea that my father was beckoning towards is a hyper significant one. That depth is only necessary for somebody who has come to terms with the fact that the surface is no longer enough for them. It’s only when the surface level appears to crack open that a person is forced into a posture of either pretending that there’s no crack on the surface or allowing themselves to look deeper. So the existential perspective that these authors or mindsets ascribe to revealed that when you look at life on the outside, it’s very often not enough. And there’s a need to penetrate deeper in order to develop one’s own personal meaning.

LEVY. So you’re really suggesting any existential sort of gateway to this is a way in. Is there a specific book or work or school of thought through which one should approach it?

ROSENFELD. So in terms of the opening towards a person’s feelings and the awareness that I need more for myself in order to feel comfortable, I think that Rabbi Soloveitchik’s, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s, books are a really, really good place to start. Lonely Man of Faith, not Halakhic Man per se, but especially and from Uviikashtem Misham. These two books from Rabbi Soloveitchik really provide the existential basis and then the leap towards mysticism that offers itself as comfort.

But in terms of introductory texts that give a person insight into the language of Pnimiyut, that’s not the type of book that I would recommend. That might be a different library of recommendations. But for the books that open a person up to enter in, books that allow the soul to be aware of the fact that something is not right on the surface…

LEVY. I find it fascinating. You know, I wrote my PhD on Rabbi Soloveitchik on Kol Dodi Dofek on looking at conversion and Jewish identity. And I would have not have sort of pitched him as the most mystical type, more and more [I would consider him a] rationalist type. There are certain texts of his when he describes when he was praying and he talks about holding onto the knees of God and begging.

And you’re exposed to a certain depth, you know, that complements the rational side. But it’s amazing that you saw that side of Rabbi Soloveitchik.

ROSENFELD. I think that what I loved most about Rabbi Soloveitchik was that all of the vessels of rationalism read to a place beyond rationalism. That Rabbi Soloveitchik was utilizing all of the constructs of reasonability and graspability. And the conclusion that he came to was that it remains ungraspable and it remains unreasonable. And in that sense, it wasn’t simply the existential posture that said life is absurd. It was a theological existentialism that said life is absurd, but that’s the way that God has created the world. And that’s the point at which a person is meant to cultivate meaning.

And so Rabbi Soloveitchik revealed to me an understanding of a statement that’s attributed to Rabbi Nachman as well as to Rabbi Chaim Volozhiner, that Kabbala begins where philosophy ends. It does not stand in stark opposition to the rational approach. It utilizes rationalism to prove its point, to show that rationalism is not enough. But we must utilize every step and tool of rationalism to get to that place of wonder.

LEVY. It’s interesting how you see that place of wonder from such a kaleidoscope of different thinkers. You’ve quoted, even so far, such a vast range. In an ideal world should all Jews be mystics?

ROSENFELD. All Jews by definition are mystics in the sense that each and every Jew has a layered expression of themselves. And each and every layer of that soul garment that represents our personality is attuned to a particular form of Torah and the understanding of the Torah.

And there exists an inner point of the soul, which is a defined concept. It’s not simply something that is kind of a spiritual idea.

It’s built upon a systematic way of thinking that the kabbalists and the mystics have conveyed from generation to generation. But there exists a part of the soul that is perpetually attuned to the deepest elements of reality, whether we know it or not.

So each and every Jew has within themselves the capacity to tune into the depths of the secrets. And in our generation there were already teachers who said it’s time to actually do that.

LEVY. Wow. And so, really it’s all connected ultimately to the oneness of God. But what do you think of when one says God?

It’s such a broad, abstract, and tangible concept at the same time. What is God?

ROSENFELD. What is God? God is what? Meaning to say God is a question that can’t fundamentally be answered. And it’s one that pushes a person into a posture of acceptance of my own human limitation. It is the idea that comes about when a person is searching for comfort and can’t necessarily find comfort. And it’s the invisible connectivity that exists between the systems that function. Systems function not because of the functional parts but because of the invisible stuff that holds it together. God is the concept that will perpetually be unknowable to the nth degree. Nowhere will we come to a place of fully knowing God. And therefore it is the wonder and the faith in God that becomes the vessel in which we can serve Him best.

So God is, number one, it’s an idea that a person attaches their mind to. It’s a set of principles in accordance with a person’s choice of path in theology. In accordance with the pathways of the theological systems that one ascribes to is going to be the shape, so to speak, the measure of how a person relates to God.

But God is the source of hope. God is the possibility of more and revelation in a world that feels like it’s always perpetually less and a place of concealment.

LEVY. So is there any sort of physical, tangible expression that you imagine when we say the word God?

ROSENFELD. Depends. And what the mystics did was they revealed to us that once we’re speaking about a singular God that is completely ungraspable, and once we’ve accepted that as the first postulate, now we can descend down into the particular names and attributes of God, which reveal God so that we can have a relationship to him on a human-to-human level.

And so every way of grasping God, and there are many ways of grasping God and experiencing God through love, through fear, through concern, through anticipation, through hope, through endurance, through the ability to be victorious over struggles,all of those are different ways of encountering an expression of God. But those expressions of God are only meaningful if we’re fundamentally aware that they are not God Himself, that they are reflections of the Infinite that are somehow conveying the Infinite without being the Infinite.

LEVY. Fascinating. It sounds like a paradox in and of itself.

ROSENFELD. This is what sod does. This is what Pnimiyut does. It basically looks at the law that determines philosophical thought from Aristotle and on up until around Hegel or after Hegel, which was the law of non-contradiction, that two opposing postulates cannot function at once. And if A equals C and B is the opposite of A, then B is not going to equal C.

But in Pnimiyut HaTorah and mysticism, we do not just deny the law of non-contradiction. We take the law of non-contradiction and we place it at the very crown of the entire system.

LEVY. Sounds like a contradiction of the non-contradiction law.

ROSENFELD. It’s an undoing of paradox and being able to live with it because that’s what every element of human experience is. It’s not just mystical speculation that brings one to this. It’s waking up in the morning. It’s serving your children cereal. It’s getting into the car. It’s starting the car. It’s being stuck in traffic. Every expression of human experience is a split between this ungraspability, and the desire to have graspability, and the attempt to wed the two together.

LEVY. So what about the Jewish people? What’s our purpose?

ROSENFELD. The Jewish people’s purpose is to be chosen for a particularly significant task, which is revealing God in the lowest place imaginable, which is this world.

The Jewish people represent the guardians of limitation.

The Jewish people are the ones who have perpetually kept their eye on the singular truth, which is that perfection is an impossibility. If we look at other offshoots that have either been perversions of Judaism or have tried to circumvent the issues that Judaism leads a person into, they try to bring about a future that is not yet here. They try to bring about an end that is not yet here, a completion that is not yet available.

Judaism at the heart of the Torah itself, at the heart of Pnimiyut HaTorah especially, is the recognition that there will always be a gap between the Infinite and the finite. And that gap is not meant to be bridged by way of collapsing it. It’s meant to be traversed by way of radically jumping over it with faith, but [we are] never [meant] to claim that we have reached perfection. So Judaism is this ancient kernel of existence that is keeping watch on the fact that we will never become as perfect as God.

LEVY. That goes to the heart, by the way, of the name Yisrael.

Because you wrestled, so to speak, with God and with man and prevailed. And that’s our namesake.

ROSENFELD. Yes, it’s exactly that. And it’s interesting that you said that because I was just thinking the name Yisrael in my mind represents this in a kabbalistic way as well. And I’ll make reference to a deeper idea because in the nature of Kabbala, there’s a principle that we must be exposed to the language prior to fully understanding what the language is saying. Because like any new wisdom, we want to be exposed to a language that we might not yet have at our disposal, but there’s no other way to learn the language without exposing ourselves to it.

LEVY. That is how a child learns language.

ROSENFELD. Exactly. It’s how a child learns language.

And so Yisrael also stands for an acronym, yesh reish lamed aleph, [which means] there is 231. When we look at the ancient texts of the book of creation, Sefer Yetzira, when it talks about the creation of the world, one of the ways in which God creates the world is through speech and the utterance of letters. And again, letters in mysticism represent everything, and it’s a much deeper conversation than we’ll be able to go over. But suffice it to say that you take one letter with another letter, so you have 22 x 21 because you have 22 letters of the aleph-bet, and you can multiply each letter against the other letter, and you get 231 shaarim, gates of letter combinations.

So yesh reish lamed aleph means that Yisrael represents the fact that there are letters in the world, there are vessels, there is concealment, there is tzimtzum. This world is not an expression of the Infinite light in a revealed way. Of course the infinite light is there, no one’s denied that, but when it comes to the graspability, Judaism is guarding the boundary.

We’re the shomrei hayichud, we’re ensuring that no one can enter directly into the yichud room, like you have when a husband and a wife get married. There’s the notion of going into that place of unity, and then there’s the guard that stands outside to ensure no one else enters in.

Let’s say God rests in the cheder hayichud, in that room of unity, and the Jewish people are the shomrei hayichud, which ensures that people don’t misunderstand or misinterpret what God’s unity means.

LEVY. Amazing. And so how does prayer work?

ROSENFELD. How does prayer work? So in this context, prayer, we’ll look at a famous way of looking at prayer through the Sefer HaIkkarim by Rabbi Yosef Albo, and this is made popular by the Maharal, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, in his Netiv HaAvodah, one of the fundamental treaties. Again, this is a very important book, a small kuntres for a person to learn, a small booklet for a person to learn. He says that the entire purpose of prayer is ultimately for the creation to remember that it’s a creature and not a creator. That prayer is ultimately about cultivating an awareness of dependency, which is an acknowledgement of deficiency.

There’s a teaching from the Bais Yaakov of Radzin, where he says that someone who’s intoxicated is not allowed to pray. Now why is someone who’s intoxicated not allowed to pray? Because the Gemara tells us that for one who is intoxicated, it appears to them as if the entire world is a straight plane without any issue. Everything is fine. And that stands in stark opposition to the notion of prayer, which is about the recognition of deficiency and imperfection. And the awakening that comes out of that imperfection and the yearning upwards in the hopes of drawing down more awareness, that’s the practical purpose.

LEVY. So I have to be of sound mind to be able to get to that stage, which prayer is there to achieve. So prayer isn’t just there for me to pour my heart out to God. That’s part of it, but it’s really there for me to be able to appreciate that God is there and who I am in that experience.

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. It’s the recognition of deficiency. And then if I’m just forced to acknowledge my deficiency without being given a tool to deal with being a deficient creature, that’s a terrifying thing.

LEVY. So prayer is my lifeline.

ROSENFELD. Prayer is the lifeline, as Rabbi Soloveitchik describes so powerfully in Worship of the Heart. And this is a famous kind of argument that Rabbi Soloveitchik brings out.

And it’s interesting. Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Morgenstern shlita also brings it out similarly, that there seems to be an argument about whether prayer is of biblical import or not or whether it’s a rabbinic dictum. And so there seems to be an argument between Maimonides and Nachmanides as to whether it is biblical or not. So for Maimonides, it is biblical. For Nachmanides…

LEVY. The obligation to pray.

ROSENFELD. The obligation to pray is only a biblical commandment in times of difficulty and pain. And so Rabbi Soloveitchik analyzes this conversation or disagreement, and he says: In truth, they’re not disagreeing. Even the Rambam, Maimonides, who says that there’s always a biblical commandment to pray, not only in moments of difficulty, he’s not denying that moments of difficulty awaken the need for prayer. He just feels that being a human being is a moment of difficulty. That’s the existential state of being separate, of being born, of being a creature that is no longer subsumed within an original unity that we can’t gain access to.

LEVY. Amazing. So what about Torah study? What’s the purpose of Torah study?

ROSENFELD. So the purpose of Torah study, and ultimately when we talk about purpose it has to be written with an asterisk in the sense that each and every person comes with their own lens and framing of the purpose, and each person’s purpose orientation is going to be unique to their standard kind of setup. And so one person’s purpose doesn’t mean that the other person’s purpose has to be the same exact [goal], so what you’re hearing is from me.

But the purpose of Torah study is ultimately to connect to the divine will that expresses itself by way of infinite gradations of concealment so that the human mind can comprehend it. What the Torah represents in its ideal form goes back to what we discussed earlier in terms of the purpose of the Jewish people. Most nations of the world, most paths of spirituality will claim that I can go directly to the Infinite. I can go and directly develop a relationship with God.

The Jewish people say you can’t do anything without the Torah. The Torah is this dividing text, this moment of revelation where it’s not God that is revealing Himself, but rather it’s God revealing Himself in something that has the semblance of being other than Him. But the radical secret and paradox is that even though it’s other than God, it still contains the irreducible remnant of God’s infinite light so that when I am engaging in the Torah, I am actually calling out to that infinite light of God that I don’t have access to.

And so the Baal HaTanya, for example, says, why do we call reading in the Torah kriat haTorah? Because it’s just like somebody who calls their friend by their name if you want to gain their attention. When you’re reading the Torah, you’re calling out to God because this is the name that God has revealed to us. As Nachmanides quotes in the beginning of his commentary on the Chumash, the entirety of the Torah as it stands in front of us right now is in truth just different permutations of divine names, meaning it all represents revelation.

LEVY. Well, there’s a tradition that the longest name of God is the Torah itself.

ROSENFELD. Yes, exactly. That the whole Torah itself is just an expression of Hashem’s revelation. It’s a revelation. And the same way we can’t grasp the essence of God, we can’t grasp the essence of the Torah itself. Because if the Torah is a reflection of God’s infinite light that has come down into the world in a concealed way so that we can engage it, so it’s a vehicle to reveal the infinite light of God, this is where the paradox becomes funny: because on the one hand the Torah is this vessel that’s holding a light, but at the same point, if you apply your wisdom to what the vessel actually is, it also contains the properties of the infinite. And therefore, the Torah itself, even though it’s a congealment of the infinite to a certain degree, it nevertheless remains inherently connected to the infinite light that it’s coming from.

So the Baal Shem Tov and the Gra, the Vilna Gaon, both make a comment on the pasuk (verse) in Psalms where it says that the Torah of Hashem is perfect. What that means is that when all is said and done, [with regard to] all of the books of Moses down to all of the last iterations of Torah novelty coming from you and I in this very moment, if we were to weigh all of that on the scale versus the Torah itself, the entire Torah would be as if it has still not been opened. We haven’t even begun to scratch the surface.

And part of what will be revealed in the incoming future revelation of Torah is a graspability that is not subject to learning. It’s not something that can be intellectualized. It’s not something that can be received from somebody else. It’s something that can be spoken around but can be only experienced vis-à-vis one’s innermost point of their soul and their personal relationship with God.

LEVY. So there are different souls, and one of the classic differences is women and men. But ultimately, we’re all unified. So does the Jewish mystical tradition see women and men as the same?

ROSENFELD. So from a historical sociological framework, no. Because these were books that were written by Jewish males for Jewish males, and the politics of secrecy and the process in which these teachings were revealed in accordance with the functional cultural framework of the time need to be taken into consideration, and to deny those are disingenuous. To claim that these books were written equally for everybody on an equal level [isn’t true] because that’s not what the historical context was.

But that’s something we call Galut HaTorah, the exile of the Torah. The unfortunate historical circumstances through which wisdom has to come down is not because that’s the main way it was meant to come down. It’s just that that is the way that it has to come down because otherwise it would be too revealed. And therefore, all of the circuitous routes of the various misutilizations of these ideas, the misappropriation of the ideas, some of the negative elements that might seem to impose hierarchies in a stronger way, all of those things, as I understand them, are symptoms of Galut HaTorah, the exile of Torah, which has to be the framework in which the innermost teachings are revealed.

When you look at the innermost teachings themselves, gender valence takes on a completely new perspective. Masculine and feminine are not necessarily seen as gendered expressions of the way a person functions but rather soul states that each and every person has within themselves. That there’s nothing that does not contain everything within it. Under the principles of unity, each and every piece holds everything in it.

And so every male has a feminine principle within him, and every feminine has a masculine principle.

LEVY. By the way, it’s like human biology and DNA. We contain cells.

ROSENFELD. Yes. You’ll see in the Arizal, Rabbi Isaac ben Solomon Ashkenazi Luria, the more and more you go into the etz chayim [the tree of life], it becomes cellular. Biology became a really significant metaphor, and it’s not meant to be reductive because the body, we’re told, keeps the score not only of the traumas of the past but the redemption of the future.

Hasidut teaches us that the body is the one that’s going to be teaching the soul in the future. So obviously, the body knows an intuitive truth of the interconnection between these different valences of giving and receiving, receiving and giving, or, you know, higher and lower, and allows them to unify themselves properly to give each role its particular space.

But there’s nothing that is given over in Pnimiyut HaTorah, especially when Kabbala is seen through the lens of its later commentaries, that it is available only for a male and not available for a female.

Now, I’m not speaking about the practice or ritualistic engagement. That depends on where a person finds themselves in the world. But spiritually, in fact, the feminine represents something that’s far higher.

LEVY. What is the obstacle to living a more spiritual life?

ROSENFELD. The body, being alive, having a heart, feeling things, having emotions, responsibility, but primarily it’s the concealment of God, which is necessitated by existence. Meaning existence necessitates the absence of God. And once God removes himself, at least on a certain level, then we’re in the dark. And that’s where the struggle starts.

LEVY. So what do we do about it?

ROSENFELD. What we do is we first and foremost acknowledge the problem. There’s a danger when making usage of Pnimiyut HaTorah that it’s going to answer the problems of divine concealment and all of the symptoms that abound.

Because, in truth, divine concealment is the source of all symptomatology that a person is going to experience in their day-to-day physiological, emotional, spiritual lives. And so we first and foremost have to acknowledge that this is the way that God wanted to create the world. Prior to trying to run and find the solution, we have to appreciate the fact that the issue is part and parcel of the model itself.

Divine concealment is the birthplace of mystical engagement. It’s the birthplace of prayer. It’s the birthplace of spiritual engagement. And once a person makes room for spiritual concealment in their lives and makes room for the fact that, wow, there must be something off if existence can exist and I believe deeply or I’m told to believe deeply in this infinite thing that denies the possibility of anything separate. So by first and foremost accepting the fact that, okay, there is a paradox that is blocking my mind from being able to grapple with this, and I have to accept that.

Then a person comes to terms with the fact that [regarding] all of those places that I felt I needed to be perfect, or I needed to have absolute grasp, suddenly they shift because now, maybe that’s not what I’ve needed all along. Maybe the fact that there’s divine concealment implies that human experience is something that has to go through a process of concealment towards revelation rather than an abundantly clear revelation. When we can undo that miseducation of what God is, we give ourselves the ability to accept ourselves and find Hashem wherever we are.

LEVY. Is there a way to educate someone like that a priori?

In other words, is there a way to not have to assume there’s a miseducation and therefore create a paradigm shift, like with your own children or if you had a school. Is there a way to do that?

ROSENFELD. It’s a great question, first and foremost, and I do believe that there’s a way to do it. But I do not believe that one can come to the benefit of these teachings without the urgency that precedes them. And urgency is born out of a moment of constriction. A person has to feel that they need something more in order to allow themselves to be a vessel that is worthy of receiving spiritual relief that comes about as a result of these teachings.

Can we teach about the mystical import of mitzvot so that ritual, kind of, boredom shifts and becomes a life-changing experience? Absolutely.

Can art and music and experience be returned back into the process of spiritual worship in a very healthy way? Absolutely. Can a person teach the utter necessity that comes about by being aware of the fact that without God, I don’t have anything in my life? That a person has to come by on their own, but there can be space given to it. This is really what the 12-step model is based on.

LEVY. Can you unpack that a bit? Even as a therapist –

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. Absolutely. And also addiction is the area that I work in and it’s one where I see a very strong expression of the inner teachings of Torah. In fact, when I worked in St. Louis in a rehab for ten years, it was with non-Jews completely and I utilized 12-step theory as well as Pnimiyut HaTorah. The only difference was that they didn’t need to know who Rabbi Nachman of Breslov was, they needed to know Nahman of Bratslav. And they didn’t need to know the Arizal, they needed to know Isaac Luria. And so these became theorists in their mind. And I found that the insight provided by our tzaddikim and teachers is so potent for each and every person. And there is a model in which these teachings have the capacity to reorient everything. In particular because of this mindset of, it’s the acceptance of imperfection, the acceptance of concealment. So when it comes to the 12-step model, Bill W., who was the founding member of Alcoholics Anonymous, understood from Carl Young and different thinkers that in order for a person to recover from this absolute need for relief, [one needs to] find relief from something higher than that, which is a higher power. A spiritual experience.

But what he was working with was William James. Now William James, in The Varieties of Religious Experience, basically set out on a particular path to figure out if there is any singular core at the heart of all mystical experiences as described throughout the cultural frameworks of history. And utilizing what he had access to, so there were limitations, but he really got a full picture. And he came to a point and realized that yeah, there is a similarity and it’s “ego collapse” at depth. That the individual faces a situation where they feel helpless.

LEVY. Is that, in Hasidic thought, bitul?

ROSENFELD. It is bitul.

LEVY. And nullification.

ROSENFELD. It is bitul. It’s nullification of self, it’s letting go of self, it’s acknowledging the limitations of self. Not by way of beating myself up because of things that I’ve done, but built into the very feature and fabric of being a human being is this imperfection. And once a person is exposed to that place then they are ready. They’re ready for spiritual experience. And so William James identifies the source of spiritual experience or revelation, on whatever degree it applied to individuals, as being this thing that happens right after hopelessness. And Bill W. basically said, let’s create this wholesale experience of hopelessness and help addicts or alcoholics confront their hopelessness immediately so that they’ll become ready for a spiritual experience.

LEVY. So it’s an acknowledgement of the void. It’s to fill the void in a certain way.

ROSENFELD. Yeah, exactly.

LEVY. And this is a way that everyone should fill the void.

ROSENFELD. But it’s the wholesale process of helping people come in contact with the void. And I think that’s the quickest way to give a person the sense of urgency in terms of Pnimiyut HaTorah. Because Pnimiyut HaTorah is medicinal. It’s a medicine. And if a person doesn’t realize that there’s a sickness that needs to be cured, then it will sit on the shelf.

LEVY. So, you know, before people become addicts, once they’re addicts, after they’re addicts – I’ve had many conversations that sort of question, challenge, or embrace free will. From a Jewish mystical perspective, does free will exist? And what is it?

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. Absolutely free will exists and we have no idea what it is. That’s how I would answer the question and I like how you phrased it.

LEVY. I need you to unpack that.

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. So we have, first and foremost, an ancient machloket between the Maimonides and the Raavad.

LEVY. A dispute.

ROSENFELD. A dispute between Maimonides and the Raavad. And it’s based on a statement from Rabbi Akiva that when it comes to free will, we have a notion that permission is granted but everything is foretold. And that already is like a Zen Koan, lehavdil, a short paradoxical statement that helps us face the paradox that is the free will conundrum. The notion that it can be settled is, I think, what has created all of this noise in our minds.

Because Maimonides says, we don’t know how it works, we don’t know what it is, but ultimately we must demand for ourselves that we hold onto this principle of free will because all of religious life stands upon it.

And the Raavad answers, he says: Why are you saying something if you don’t know what you’re saying?

Meaning to say, I agree with you there’s no way of explaining it, but in a place where something can’t be explained, it’s better to remain silent. So there in that argument between Maimonides and the Raavad of speech and silence, Maimonides is speaking and the Raavad is saying it’s better to remain silent. It’s [something] within the speech and the silence that gives birth to the vessel needed to understand free will.

Because free will, on the one hand, is the radical reality that in this moment I have the ability to do what I want to do in accordance with my best reasoning and my best thinking, and it’s up to me. The realm of yedia, or foreknowledge, can best be explained by human conditioning. Meaning, even within the realm of a perspective that says a person has complete free will, in accordance with one’s behavioral conditioning and the micro and macro systems that have influenced their lives, a person’s free will is a very limited swath of space. Very similar to what Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler explains as the point of free will, that each and every person has a relative position in where they have yet to decide what they need to do. But it is determined by things that have taken shape beforehand, and when it comes to the determination of things by way of what the future will look like, that’s where we lose our ability to fully grasp it.

The best answer to this is [that a] person has to look in the books to read everything that’s written about free will and determinism, but the formula is as follows: A person has to choose to live from a perspective of the foreknowledge of God, that we always have the choice to relinquish our sense of control and the volitional freedom that we actually hold when we give it over to God, and we realize that even this part of my life that I feel is devoid from You is also connected to You, and that is the choice that remains present in front of a person at every moment.

LEVY. So we talked about the future and what that holds. We have a fervent belief in Mashiach. What does the Messiah, what does Mashiach mean to you?

ROSENFELD. What it means to me is a radical shift. A radical shift from negativity towards positivity in the most general of ways.

How or why? Then a person has to begin to look at Maimonides and see the political and historical timeline in which the various stages take shape. And there is an immense amount of material and statements of Chazal and the rabbis that go on to determine the historic process exactly.

But from an inner perspective, what the Baal Shem Tov came along to say is that once we have this unity principle that basically operates from a holographic perspective, where because everything is coming from the infinite, everything contains within itself the residual lights of the infinite. And if everything contains within itself the residual lights of the infinite, then everything in earnest contains an element of the infinite within itself.

This gives birth to an equality of the whole and the part, almost like on a fractalized level.

Mandelbrot’s fractals basically teach us that no matter how different the size quantity of an expression is, on a qualitative level you will come to find that it’s the same simple substructure at the heart of all things.

This is basically what the Arizal is describing with the process of the sefirot, [the ten attributes of God], that everything in the end of the day has its own subset of ten sefirot that make it what it is and not some other thing, and then through the process of individuation each thing becomes its own thing.

That’s all to say that if there’s a redemption in the future, then there’s also a redemption in the present. And if there’s a general redemption, that means that there’s a possibility of redemption that exists within the particular as well. So first and foremost, the person wants the particular redemption. Particular redemption means relief. It means nechama, it means calmness. It means comfort. In truth, it means whatever a person expects it to mean in their best thinking.

There’s a teaching that in the future we will be like dreamers, that when Mashiach comes we will be like dreamers, and we learn in the parshiot of Vayeshev, Vayishlach, Vayeshev, and all of those different stories of Joseph and his brothers, that dream interpretation follows the interpretation of the interpreter. That I’m going to see in accordance with what I expect, and so too with redemption. In accordance with what I expect is what I’m going to receive.

That’s the inner redemption, and then the historic redemption is the thing that we hope towards. The real redemptive quality that Mashiach brings into our consciousness now is the possibility of hope towards a future that is radically different and better and more redeemed than what we experience now, and in that, the hope towards redemption is far more of a radical notion than even the arrival of redemption itself.

LEVY. So you talk about this hope towards redemption in the sense of a historic process, and then you’re able to look at it in the individual sense where I am in the here and now. How does this fit on a national level for today, i.e., the state of Israel and the final redemption?

Is this part of the process?

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. If we’re here, it’s part of the process. Everything that’s taking shape in Jewish history is part of the process.

Jewish history does not run in accordance with human reasoning. Jewish history has a split screen to it, and this is something that the Ramchal, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, and Rabbi Shlomo Elyashiv, the Leshem Shevo V’Achlama, explain most powerfully, although it’s something that’s expressed throughout the writings.

That there are two expressions of the historic process: there is the consciousness of Jewish history and there is the unconsciousness of Jewish history.

And on the unconscious level God is running the show from beginning to end, and every act that appears to be a descent is ultimately for the sake of an ascent, and there is no limitation. There is nothing that is actually going wrong. In truth, everything is building itself up. It’s referred to as Nora alila al-bnei adam, that God works with history in kind of this circuitous way where He is ultimately the one in control of history.

From this perspective, Adam didn’t have much of a choice as to whether he was going to partake in that first transgression. It was built into the narrative. Cain and Abel didn’t have a choice. Egypt had to happen. Joseph and the brothers, all of that had to happen. All of the gradations and exile had to happen. So from that perspective, everything that is taking shape in the Jewish people’s history is a fundamental part.

And what has to happen throughout history is refinement after refinement after refinement after refinement. So there are ideas that are developed, and then there are antitheses to those ideas, and then there’s a synthesis that comes and helps an idea refine itself and grow beyond itself.

And I believe that what we’re seeing far more in an open way right now is a re-attunement to how we thought a lot about previous ideas, and people are now opening themselves up to reorienting themselves to new ideas.

So, what belongs in a person’s framework of redemption will continue with them. And so, the elements of the Jewish State, the elements of the Jewish unity that come with having a homeland, the elements of Jews being protected in a homeland, the elements of camaraderie and unity and a sense of homeliness, all of these fundamental aspects are redemptive qualities that belong at the heart of Klal Yisrael, the Jewish people.

And then there are going to be other elements that a person might be exposed to when they’re exposed to states and governments that they’ll come to question as to whether those are ideas that they see fit as being revealed in the final product of Klal Yisrael. But there’s absolutely no question that the State of Israel and the process of the State of Israel is a fundamental revelation of God’s desire throughout history.

And I mean, even if I didn’t agree with this, I saw it in my grandfather coming out of Auschwitz, and my older brother was in the IDF. He learned in Yeshivat HaKotel, and then he became a chayal boded [lone soldier], and they were staying at the Prima Kings Hotel, my Saba and my Safta, my grandparents, and my brother came to visit them in uniform, and my Saba’s body reaction was ultimately of such import and such revelatory significance that he said these were the malachim [angels] that we davened for. And so, at a certain point, that’s undeniable. It’s undeniable that the nature and the status of Klal Yisrael right now are, in a way, far closer to the vessels needed for redemption.

But again, the problem, like anything else, is if we forget our main mission, which is to remember that the end is not complete yet. The end is not complete until the end is complete. And the danger is identifying an unfinished product with something that’s complete.

LEVY. It’s almost like God has hastened this redemption and now requires us as partners to be able to help complete it in this partnership.

ROSENFELD. Absolutely, right? The hastening, there’s a speed at which history is taking shape now, right? Each day is a thousand years. And this comes back to a simple notion of the messianic advent and the arrival of Mashiach, which can take place in two different ways: be’itah, in its time, or achishena, if we hasten it.

These two models of redemptive consciousness and the arrival of redemption, something that the Vilna Gaon and his beit midrash [study hall] spoke so much about, are that from the framework of messianic redemption in its proper time that God has ascribed, that Chazal have calculated in their own ways, that means that history will do its work but eventually we’ll get to that final product. History doing its work means that it won’t be too intense at every moment. There will be pockets of intensity, but history will do its work. Achishena, meaning hastening it, is that no, we want it now, and we don’t want to wait, but what that lends a person to be exposed to is the fact that those historical rectifications need to take shape.

And so, what happens if you truncate the time period is that we open ourselves up to the possibility that more intensity, more difficulty, more historic significance in shorter amounts of time will be needed in order for the accounting to be done properly. All of those are sugyot that belong to the tzaddikim. Ultimately I try and follow the Lubavitcher Rabbi on this matter, which is that everything is kind of done and fixed, and it’s our job right now just to demand from God actual redemption because a person can give Torah on everything in the world, Pnimiyut HaTorah can reveal everything, but when it comes to the suffering of another Jew, there’s really no Torah to be said about it. And at that point, you just need redemption.

LEVY. I love how you weave together the historic process of the State of Israel, what it means, as well as the books. And what I find most visceral is a recollection of your brother coming in Israeli army uniform to your grandfather who came through the Holocaust.

And I guess that’s your life, right? On the one hand,you’re deeply immersed in these books. On the other hand, you’re sitting with people that are broken and trying to help them to rebuild themselves. And I guess if you can, can you extrapolate from that in terms of what is the greatest challenge that’s facing the world today? Can you take a meta look from the personal, specific look and say what is the challenge today? What is our greatest challenge in the world?

ROSENFELD. It’s an amazing question, and I think that the greatest challenge is a lack of belief in self, which stems from a lack of knowledge of who we are and what we are.

Rabbi Nachman has a way of describing it, that the greatest rachmanus, the thing that evokes the most sympathy because of the pathos inherent in it, is when a Jew is unaware of what rests inside of them. That the Jewish soul is a technology that God has placed into the world in order to allow the world to enter into its purposeful state. This is what we’re guardians of. Each and every one of us carry within ourselves vistas of meaning and interpretation and significance and value to the degree that each person is the reason the world was created, and each person is the reason that the Torah has been created, and if a person saw themselves as the only Jew in the world, no matter where they find themselves, then the mission remains solely on their shoulders. And Maimonides says we have to see ourselves as in a state in the world where the valence of the world depends on our behavior.

All of this is there to build us up. Moshe Rabbeinu [Moses] has already gotten rid of the guilt and the shame for us. When Hashem wanted to destroy the Jewish people after Chet HaEgel [the sin of the Golden Calf], Moshe Rabbeinu basically said: God, do you want to know what this is like? And Moses is always very docile, and he doesn’t argue with God. But when Hashem wants to punish the Jewish people, Moses acts like the parent that he is, and he says: This is like a young child who has money placed around his neck, and he’s sent in front of the brothel. Are you going to blame the child for sinning?

And yet, historic consciousness, no matter where a person falls on the line of Jewish identity, something that we’ve all received robust portions of is that shame that comes about by feeling that we’re at fault, that there’s something not right with us and that we’re incapable and [have] a certain meekness or weakness, etc. And what Pnimiyut HaTorah and what the Torah comes to do ultimately is reveal the profound level of strength and responsibility that a person has.

That doesn’t mean each person will build a building, but it means that any time that I get out of bed, sometimes in the morning, that victory might be the thing that history needed to push it to the finish line.

Each and every person is fighting their own battle, and each and every person has untold strengths, and what Pnimiyut HaTorah does is it gives us insight into what the neshama [soul] is.

LEVY. So I asked what the greatest challenge for the world at large is, and you said essentially it’s that every single individual in the world needs to believe in themselves more and have the capacity to be able to face those challenges.

ROSENFELD. Yes.

LEVY. So really, we can each conquer that challenge as individuals, and collectively then we’ll succeed on a global scale.

ROSENFELD. Yes, and again, this interpersonal realm is fundamental when it comes to Pnimiyut HaTorah. One might think that if you look at Pnimiyut HaTorah, you’ll come to the inter-divine realm where it’s me and God or me and myself, perhaps. But self and other and community, that seems to almost run away from the notion of mysticism, which is more of an isolationist kind of perspective.

One of the unique things from the Zohar HaKadosh and on, and it applies to nearly all of the groups of tzadikim [righteous people], is that there were chaburot and there were chavrayas, there were companions, and there was friendship, and there were teachers, and there were students, and there was engagement. There was wisdom being shared and wisdom being cultivated, and so other than just the educational model, there was already an exposure to other people. And so the mystic was never left in their own isolation. They were always being exposed to individuals.

Are there certain mystics and tzadikim who hide away from the world? Sure. Enoch was a model of that. He walked with God. It wasn’t his job to engage. But nowadays, the biggest thing that we can do is face another individual and try to offer them relief. That is the fixing of the world because when each person comes to their deepest point of strength, then we realize that the most important thing to do is to do a favor for another person, to give.

LEVY. Yeah, I always found it fascinating that the place where the divine presence is revealed is between the Cherubim, and they’re facing each other. And I thought, how can you put idolatry, these images, in the Holy of Holies? But I think it’s teaching us a lesson that God is revealed [in the] interaction between individuals.

ROSENFELD. In the face. In the face.

LEVY. Looking at one another.

ROSENFELD. Yes. And it goes, just to bring it back to that 12-step model, the 12th step at the end of that 12-step process is going out and sharing the message with somebody. So is that because they need more foot soldiers? Perhaps, but what’s also inherent within that model is that sharing with another person is, in truth, the most selfless thing one can do.

But sharing with another person from a perspective of strength of self is the true secret. So that’s why when we uncover our own strength, naturally we’ll then have the strength to enter into a proper relationship.

LEVY. Beautiful. So if we look at now, I mean, you’re a scholar of modernity and even post-modernity. Has modernity changed Jewish mysticism in any way? Is it different now?

ROSENFELD. Yes. It’s given us language. I mean, when we look at the development of the printing press and we look at the development of different ideas, we can trace the trajectory of how Pnimiyut HaTorah has unfolded, but at a certain point, novelty ends and then it begins new expressions of the same ideas.

That’s one of the marks of Jewish mysticism, that it’s Kabbala. It’s something that’s being received from some place beyond. It’s not something that is intuited, God forbid. It’s not something that is developed.

It’s built on a principle that we believe rests all the way back at the revelation at Sinai. There’s the tradition that the secrets of Torah are also conveyed to Moshe Rabbeinu.

Modernity has exposed individuals to more of the world, [including] more of the temptations of the world and more of the areas of struggle, which makes the need for Pnimiyut HaTorah even more significant because, as Rabbi Steinsaltz pointed out, it’s hard to identify any real Jewish theology other than one that is based on Jewish mysticism without providing at least a comparative model of meaning-making that demands an exposure to deeper ideas, which are always going to lead one to Pnimiyut HaTorah. So then a person is going to be lost in the framework of modern ideas.

So modernity, first and foremost, adds to the urgency of the revelation of these teachings because you have to fight fire with fire, and at a certain point…

Rabbi Kook made a statement that said there will come a time in the future where it will be impossible to convey even the slightest semblance of Jewish faith without the utilization of the deepest ideas imaginable, and I imagine that time to be now.

So on the one hand, modernity unleashes a hitherto unrevealed urgency for these teachings, but language, I believe, academic study, critical study, understanding where these authors were coming from, where were they living, what was the day-to-day life there, what were the larger frameworks in which they were expressing their ideas? I think that lends a profound amount of significance to seeing the relevancy in the text and giving us the ability to translate the ideas in the text to similar metaphors or systems of metaphor that make it more practical.

LEVY. So what about Jewish mysticism as opposed to other traditional mysticisms? So many cultures and religions have mystical traditions. What makes Jewish mysticism unique?

ROSENFELD. So first and foremost, I can’t speak for a deep exposure to other systems of mysticism other than by way of a general kind of understanding. I’ve never, thankfully, had to spend time there.

I believe that when you do kind of the historic digging, you come to find that most models of mysticism that provide some semblance of, kind of, modern sensibilities to either European or American minds are ultimately rooted in the translation of Jewish mystical texts. You see that Jewish mysticism from the get-go has had a profound influence on the development of so many of the other mystical paths, and there’s an immense amount of literature and academic studies that have been done to show the rootedness that most mystical models have within certain expressions of Jewish faith.

LEVY. So there may be commonalities because it actually comes through from that source.

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. And we also have a tradition that there is a certain universal nature to divinity. In spite of the fact that the Jewish people have a unique way of grasping it and holding it and relating to it, that doesn’t mean that there’s no exposure of these general principles to others. Aderaba – the opposite is true. We understand that there’s a real notion where someone who is doing their thing in the right way, the need is not to become Jewish, but rather to do your own thing in your own way, and you can experience those same illuminations.

But other forms of mysticism, as I have come to understand them in the general and over-generalized critique, is that they provide a certain element of immediacy.

They provide a certain sense of graspability or something that is taking place right here, right now, that I can lay claim to, and I can tag it, and I can weigh it, and it becomes like an idol for me.

I think that inherent to Jewish mysticism [and] the Torah is the denial of icons, is the shattering of icons. Avraham Avinu shattered idols. Abraham entered into the unknown. Jewish mysticism is [beckoning] us more and more to what we don’t know. It’s a profoundly negative theological process that gives way to a true experience, but we’re not laying claim to anything. It opens up more and more wonder. So it’s nonviolent. It’s not trying to own anything, as opposed to other models, which are rooted in, kind of, what can I lay claim to.

LEVY. And does one need to be religious to study Jewish mysticism?

ROSENFELD. One needs to be religious if they want to study Jewish mysticism in a religious context. If a person wants to be someone who’s studying the texts in accordance with the way that they were written and conveyed, then adhering to the same framework of religious orientation and ritualistic engagement that the authors of those texts engaged in will obviously give a person far more of an accessibility to the text because of the familiarity as well as the lived experience of it in terms of the ritual framework.

That’s not to say that the ideas cannot be abstracted and translated into various forms of metaphor that provide profound levels of significance and profound levels of insight to each and every individual. Where I begin to kind of make a distinction for myself is that I will look at ideas that are conveyed by people who might not necessarily be religious as I understand it in terms of the stricture of it, but I will not look to it as a fundamental interpretation of the system that needs to be taken into consideration.

But I believe that the Torah is the lot of all Jews, and each and every person has exposure to what they’re exposed to, and the fact that there’s a proliferation of English writings [means] that it’s more difficult nowadays to not know than it is to know. Meaning there are real teachings being revealed in real time in a very graspable way, and I believe that we’re entering into a period of time where the medicinal element is so necessary that we’re willing to just throw everything in the hopes that one drop will go in.

LEVY. So now that it’s accessible to all, is there anything we should be aware of? Is it dangerous?

ROSENFELD. It is dangerous in the sense that it can cause a person to lose their mind. That’s always been the concern. The concern has always been that it causes the stories after, if you learn it before forty, etc., then you become a meshugana, [that] you lose your mind.

The loss of the mind over here is not obviously symptoms of mental health necessarily. That’s a separate category of experience. But a person can either be overwhelmed by the enormity and infinitude that is affirmed in Jewish mystical teachings to the degree that the need to do anything or put in any effort or even refrain from anything is a really hard sell because when you’re dealing with absolute infinitude and everything is okay, that can lead to certain desires.

And I think that we saw this historically with Shabtai Tzvi and that group. What took place was that these teachings did become permissive and did allow for particular behaviors, which kind of denied the stricture and the rituals of halacha and the framework of holding back.

The other danger is that a person can become too afraid and too obsessive because Kabbala can also speak about demonic forces, and it could speak about, you know, spiritual impurity, and it can speak about sensitivities that the conscious self is not aware of but that other parts of the self need to be aware of. So to a superstitious mind, it becomes dangerous.

So on those two polarities of either going too far into the light or getting too stuck in the vessels of it, it’s dangerous. On the middle level, the danger is a person can come to think that they’ve perfected something.

And this is the importance that Hasidut and later interventions of Jewish thought have introduced into Kabbala: relativizing the system of saying that because Kabbala speaks of a ceiling. But what Hasidut says is that the ceiling is just the floor of the next level.

LEVY. So how has Jewish mysticism affected your view of relationships with yourself and with others in a practical way?

ROSENFELD. It’s given room to all of the various complex and changing parts. And it’s enabled me to understand that simply because a relationship is not going in a singular way of expression does not mean that that relationship is broken or struggling. It just means that a person has to attune themselves to the various parts that compose relationships.

Because the model of relationship in the writings of the Arizal and Jewish teachings, which can really be seen as – I believe in the name of Rabbi Shlomo Twersky, a very interesting tzadik who lived in Denver and passed away not so long ago, he said that the book of the Arizal is ultimately a book of [a] relationship, and it’s the best book of [a] relationship. But every relationship is not just face-to-face. There’s a back-to-back relationship and a face-to-back and a back-to-face and all various forms of interconnections. And when I look at a relationship I have, and if I was expecting that person to be one way because they were that way before, if I only have one way of looking at the relationship, then there is something wrong here. But if I open myself up to the realization that nothing is one single way and I can open myself up to the shifts and the turns that mark human experience, I can say, okay, this is just the parts that are expressing themselves in this relationship, and it’s different but not separate.

LEVY. Can you give one practical example with your kids, with a client, with your wife, with a friend?

ROSENFELD. Absolutely. So I’ll give one with a client, which is an important piece, and then I’ll give one with a child as well. So with a client, you can, in my field of addiction, you can be talking to someone in recovery from a substance, right? And in the moment of truth, when consequences are there and they’re really ready in their most earnest depth of heart to let go of what they’re stuck in, when they say they don’t want to go back to their old behaviors, they absolutely mean it.

But when they’re exposed to their triggers again and they go back to the old hauntings and the same places that they went to and the body is kicked into gear and then they find themselves in the same old behavior, so [using] the old model that says one relationship is one way and only one way, I see someone who’s lying to me. And I’ll become frustrated and say I can’t work with this person because one moment they told me they don’t want to be doing this and now they’re doing it.

But if I open my mind up to the fact that no, there are various ways that a person functions and the various points of interpretation of where the person is holding, when the person was in a state of mind of recovery orientation, they never wanted to use again and they meant that fundamentally.

But when a person is struggling with their trigger, they’re exposed to that part of themselves that still wants to use. And instead of saying oh, you’re a split person and you’re lying, I can embrace the person as a complex set of parts that compose a whole rather than looking at them in one single way.

And I think the same is true with a child. If a child is showing you nachat, a child is doing something that makes you feel proud about them in some scholastic presentation or they’re doing well in their reading, so you could be proud of them. But then if they’re showing boredom or disinterest in the ritualistic element of Judaism as it’s being taught to them, I don’t have to say oh, this child hates Judaism or wants no relationship with it or I’m teaching it wrong. It just means that they’re connecting to the learning element of it but not the prayer part of it. And those are two different relationships.

LEVY. So to conclude, we’ve talked a lot about Jewish mysticism. Can you teach us a thought in Jewish mysticism? What’s something that you take with you, an inspiring thought or a Jewish mystical teaching?

ROSENFELD. Sure, absolutely. So there’s a model that the Arizal kind of brings down, and it’s one that rests at the core of my philosophical outlook, my spiritual outlook, my psychological outlook, and it’s just something I’m thinking about now, but it’s called Shevirat Hakelim, Shattering of the Vessels. The Arizal tells us, based on the Zohar, that in the original process of the creation of the world, God created an initial stage of functioning, and that stage of functioning shattered and it didn’t work, and it was a traumatic breakdown, and all of the broken parts of that original stage fell down into kind of disarray, and it’s specifically in the place of those fallen sparks that history and reality take shape, and that’s where our work is.

So what I love most about this is that it reorients us to the nature of trauma. We live in a generation of trauma. There’s a real argument that can be made that anybody who’s been alive long enough to have experienced [trauma], you know, for me it started with, other than being a grandchild of survivors, 9/11, rachmana litzlan, is what I remember most, but since then there’s been at least four or five capital T traumatic events just historically or globally.

So we are functioning in a state that is a post-traumatic state of being, and with the over-traumatization and the language of trauma, a person comes to misunderstand what trauma is. A person thinks things were meant to be perfect and then they broke apart. There was the trauma, things shattered, and now I’m left trying to deal with a broken world but to make meaning out of it and find the second best option.

But that’s only when we see trauma as a disruption to an original whole. What Judaism teaches is that there was never an original whole.

The only original whole is God. The moment that God decides to create the world means that we’re no longer dealing with that original whole, and then everything is by definition deficient, and therefore the traumas that come out are not destructive; they’re constitutive of the very thing. It’s a breaking that builds, and when a person sees those breakdowns in their lives as opportunities to build new levels of meaning rather than to be stuck in this post-traumatic sadness over having lost something irretrievable, then we begin to make room for God in the parts of our lives where we didn’t think he could be found, and that’s the real job of a mystic. The real job of mysticism is to reveal God where he’s not found, and the more I can incorporate the broken, difficult, concealed parts of my life, the Shevirat HaKelim of it all, and I can understand that it’s deliberate and by nature and it’s for the sake of growth and building, then I’m going to be able to multiply my experience and my relationship with him and find meaning in everything.

LEVY. Rabbi Joey, we’ve seen that really through these eighteen questions you’ve infused that sense of healing the fragmented world around us, and we give you a blessing that as a father, as a husband, as a therapist, and as really a teacher of thousands of people around the world, you continue to do that and you’re able to allow people to understand the Shevirat HaKelim, this fragmentation, but also understand that through the brokenness is the opportunity to build. So thank you so much.

ROSENFELD. Yasher Koach, Rabbi Benji. Okay. Amazing.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Dr. Ora Wiskind: How do you Read a Mystical Text?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Dr. Ora Wiskind, professor and author, to discuss her life journey, both as a Jew and as an academic, and her attitude towards mysticism.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Debbie Stone: Can Prayer Be Taught?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Dr. Debbie Stone, an educator of young people, about how she teaches prayer.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

5 Lessons from the Parsha Where Moshe Disappears

Parshat Tetzaveh forces a question that modern culture struggles to answer: Can true influence require a willingness to be forgotten?

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

Rav Tzadok of Lublin on History and Halacha

Rav Tzadok held fascinating views on the history of rabbinic Judaism, but his writings are often cryptic and challenging to understand. Here’s…

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.

videos

Talmud

There is circularity that underlies nearly all of rabbinic law. Open up the first page of Talmud and it already assumes that…