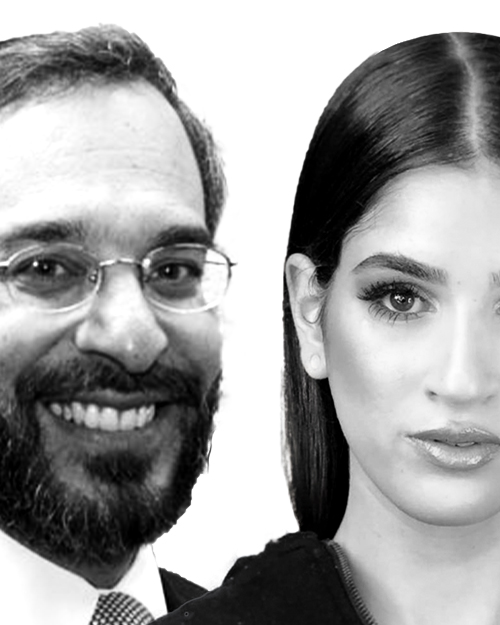

Dovid Bashevkin: A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi [Denominations 2/2]

David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko about denominations and Jewish Peoplehood.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations and Jewish Peoplehood.In this episode we discuss:

- How did David become an Orthodox rabbi with an interest in the broader Jewish world?

- Where does David get his sense of commandedness and obligation from?

- How should Israel factor into our thinking about Jewish unity?

Tune in to hear a conversation about what it would mean for us to speak Judaism as a “first language.”

Interview begins at 29:05.

Diana Fersko is the Senior Rabbi of The Village Temple, a Reform synagogue at the heart of downtown Jewish life in New York City. An internationally recognized author, speaker, and thought leader, she is a defining voice in the contemporary Jewish world, known for her clarity, compassion, and ability to bring Jewish tradition into meaningful dialogue with modern life.

For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_forty

WhatsApp: join here

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Bashevkin: Hi friends and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and today we are continuing our special two-part series in dialogue with my friend Diana Fersko about Jewish peoplehood and denominations. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 1840.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. Four years ago, I had a conversation with a mentor of mine, Moshe Benovitz, who was encouraging me to think about 1840 and where I was going to take this idea, this movement as we were just beginning.

And I remember him telling me, “You need to tell people what you are doing differently.” Meaning there’s something that I think instinctively people can understand or intuit that we talk about the Jewish people and Judaism in maybe different ways than others or maybe we have a different approach or a strategy or even a term that I loathe that is used sometimes in the Yeshiva world, a different hashkafa, which is like a religious outlook. And he was pushing me that like, “You have to tell them what you’re doing. You have to kind of explain why is what you are doing any different? Unless it’s not,” you know, he was saying, “unless it’s not, unless this is just, you know, a podcast where you interview interesting people and there’s, you know, no shortage of those and you certainly, you know, could compete in that domain if that is what you want to do. But if that’s not what you want to do, then you need to explain what you do want to do.” And I don’t know if I ever fully answered him.

I am still probably developing that answer for myself, being able to articulate what is it that we are doing differently. And I want to surface that now in this second part of my conversation with my friend Diana Fersko, who serves as the rabbi in the Village Temple synagogue in Manhattan. The first conversation I interviewed her, and this conversation she invited me to speak to people from her community and she interviewed me. What am I trying to accomplish here? And secondly, why is it that I make the case or talk about Judaism in the way that I do? If you listen to this conversation, I have no doubt that this is not normally the way people make the case for Judaism and Jewish life.

And I think that this starts to get to the heart of what we are trying to accomplish on 18Forty. As long-time listeners surely already know, we called 18Forty by its name, 1 8 F O R T Y, after the calendaric year 1840. The calendar year 1840, which is right when the Industrial Revolution is bubbling up, when a new wave of messianic expectations hit the Jewish community, and is also the anniversary of the founding of a Chassidic movement known as Izhbitz, who was the teacher of the Chassidic thinker, the Jewish thinker who I consider has influenced my thought the most, and that is Reb Tzadok Hakohen Mi’Lublin, who is a student of this rebbe, the rebbe of Izhbitz, known as Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner. What does this have to do with anything? Like, what is it that we are doing differently? So I want to try to articulate it because I think it stands at the heart of this conversation.

I think for most of Jewish history, we had a very specific way of making the case for Judaism internally to ourselves. First and foremost, most Jews were Jewish because that is the world that they were born into and they didn’t really have other options. You know, the story that they carried was a very powerful story, but in many ways was a very simple story. It is the Jewish people received the Torah at Sinai, that included a written Torah and an oral Torah, it had all of the commandments, and to be a Jew was to follow the commandments of God to the best of your ability, and that is what Jewish life became synonymous with.

There were different periods of Jewish history where levels of observance went, you know, up and down, but essentially the ideal of what Jewish life is supposed to look like was very, very uniform. There were definitely splits that began between the lands of Sfarad and Ashkenaz, different parts of Europe, different customs began to evolve, but in terms of how would people justify Judaism in their own eyes, there was a fairly basic and essential story. Maybe the word essential is easier than the word simple, though I like the word simple also. You know, we received the Torah…

Torah at Sinai, it had an oral component, it had a written component, and we are continuing to follow the commandments of God in this very time and we have enemies and we are persecuted and this was a story that was held and cultivated by Jews continuing to this very day, to this very day. If you go to yeshiva, what is the essential story of the Jewish people? It is something to do with that. We received a Torah at Sinai that had commandments and that is kind of our role in this world. Things began to become much more complex very slowly and I am simplifying the story of the simple worldview of Judaism.

But what motivated Jewish life was definitely a fear of if you break the commandments, if you don’t follow the commandments, God will punish you and your life, you did not want to be punished. And Haym Soloveitchik writes about this at length about that conception of God of striking somebody down with illness or with poverty or persecution was very visceral. It was the way people understood the world. And then modernity came and with modernity came much more intense examination of the truth claims of Judaism and that began from the very top.

That there is a God, that the Torah is of one cohesive unit, that our interpretation of the Torah is the correct interpretation. And people began to really debate about that very kind of essential picture of Judaism and people both good people and people with everybody has motives but people that had motives really to enhance Judaism were also involved in asking these questions of trying to reground the basis of Judaism for the modern era. And that most essential story when the tools of skepticism and academic inquiry and historical examination for many people though not for all people it became harder and harder to continue to grasp on the most essential story as our understanding of the world through the scientific revolution and the industrial revolution became more and more complex. I don’t think it is heresy to say that as our understanding of the world evolved in many ways our understanding in the way that we cultivate a relationship with the divine evolves as well.

When you are looking at a world a thousand years ago, not to say God forbid that we don’t believe in an active God in the world and in creation, but our understanding of the rules of nature have evolved dramatically in the last thousand years. We take them much more seriously. We understand them much more concretely. And because our understanding of the universe has become so much more complex, so much more rich, it is also necessary that our understanding of God for many, though not for all, depends what your interaction is with kind of the rapid evolution, but for many your understanding of what of God, of Yiddishkeit, of Judaism, of our own history, for many we need a more complex story as well, which is why it was during this period that people in the traditional in the Orthodox community for the first time ever began writing books of Jewish history.

Began writing books that try to make the claim through historical analysis rather than just kind of a founding story of the Jewish people they tried to really develop. A good example of this is Yitzhak Isaac Halevy wrote the book, it’s like an eight volume work of Jewish history, but it has a very clear claim that the way we understand Judaism today has remained consistent. Why did it take so long for a Jew to write a work of this nature? A work explaining kind of the evolution of Judaism. This was in response to others who told a competing vision of the evolution of Judaism and now we have these competing stories of what is the story that we have inherited? And I feel like as modernity began that is when these competing stories began to kind of evolve where you had a traditional Orthodox community that made its claims for the truth, you had a let’s call it a neo-Conservative community that made its claims for the truth and you had a Reform community that made its claims for the truth and we had these kind of competing stories.

Now I don’t think these all have equal historical basis or merit. I believe that the Orthodoxy I practice is very much grounded in history. But one of the reasons why that claim is much more difficult to make as an obvious truth claim that of course Orthodoxy is the correct interpretation of Judaism is that there are other strands and other interpretations that also claim to have that basis, that also claim and have very rich underpinnings that it is very hard to make the case based on first principles with all of the information that we have access to, how to make the truth claim of where we stand today that this is the correct interpretation of Judaism. That became much more difficult with the advent of modernity, when we began having debate about the foundational evolution of what is the story that we have inherited, what is halacha, where does it derive its authority from, how does it work? Is there kind of a core basis of the Jewish idea, what I talk about like a common Judaism? If you would have asked a Jew for most of Jewish history, you know, which version of Judaism do you practice? Scholars call it was common Judaism.

It was, I don’t know, it was whatever my parents did and there was a very rich tradition that lasted millennia. But in the modern world, it is much harder to make that justification. That is not to say that the more simplistic story is not true, but it is harder to justify based on first principles, given the amount that we have access to. If you talk to a random Jew on the street and you want to make the case for your specific model of Judaism, that has become much more difficult.

I am not saying that it is impossible and I’m not saying that others do not continue to make the case for a very specific model of Judaism to this very day. I think that’s very much the program of Jewish outreach in many ways is making the case for Orthodox Judaism as a model based on first principles. And yet, not everybody becomes Orthodox. If it was that easy to justify our 2025 truth claims of what is the model of Judaism, we wouldn’t have as much debate.

We still have a tremendous amount of debate and I don’t think it’s just because some Jews are more or less lazy than other Jews, or some Jews are more or less even educated than other Jews. I think that we live in a different era of modernity where kind of that claims to authenticity need to be articulated in new ways. That the ways that we used to justify or make meaning or make purpose out of our Judaism, the stories that we would tell ourselves and others have necessarily evolved because our understanding of the universe has gotten more complex, which necessarily means our understanding of God and Yiddishkeit has gotten more complex that gave birth to competing stories of what Judaism even is. I believe nowadays we need a new methodology, a new path that isn’t the exclusive path and it is not to the exclusion of any others, but it is a way of making a case for Jewish life that instead of having fights with just what’s the correct truth claim or what’s the correct history where scholars have been debating this for centuries right now, it is learning a new language for how to make sense of our own Jewish story and that is what I believe I am trying to do on 1840.

That is a very long way of saying I believe that the era in which we live necessarily—I don’t want to use the word requires—but there is both an urgency and an opportunity that we need to develop a new language with which we think about Judaism and Jewish life. That is not to tear down denominational boundaries, it is not to make light of the ideological differences, but it is to almost acknowledge the fact that just by our classic methodology and reasoning, it is going to be very difficult for any one version of Judaism to lay the exclusive claim on the truth. It may be that it is true that there is one community that has the truth. Maybe that’s true.

Somebody can believe that, but we need to learn how to tell our story differently. We need new language to make the case for Jewish life for ourselves and for others. Because one thing I can tell you for certain: there are a lot of people in a lot of different Jewish communities who are really struggling and suffering with their own understanding of what Yiddishkeit is. And I think a lot of the ways in which we explain what Yiddishkeit is is not working and that’s not working most obviously in the non-Orthodox community and it is not working for a lot of people within the Orthodox community.

And what I am trying to accomplish on 18Forty is develop a new methodology with which we think about Judaism and our own Jewish life that necessarily involves us reorganizing the boundaries of who we listen to, who we dialogue with, what we dialogue about, what we talk about, the questions that we are willing to ask and who we are willing to ask those questions to. But I think there is something even beyond that and it’s not just a question of what we talk about, but the very understanding, our conception of Yiddishkeit itself. And this gets into… This is not my own analogy.

This is an analogy that I first learned from a previous 18Forty guest and someone who I consider a mentor and a friend, Moshe Koppel, who wrote in Azure in the 46th issue, in 2011, this was an old journal, but he wrote an article called “Judaism as a First Language.” Many of these ideas were repeated again in his book called Judaism Straight Up. But I really like what he says and how he describes what Judaism is. And this is what he writes: Judaism in a way is not that different from English or any other language for that matter.

In fact, Judaism is a language of sorts. Its internal dynamics, the manner in which it evolves, and the powers through which it is fashioned are all startlingly similar to those of the linguistic process. Now, one can treat this comparison as a mere intellectual exercise, an interesting metaphor at most, but I believe its potential implications are great and far-reaching. It can shed light on some of the problems that keep many contemporary Jews, myself included, up at night.

If Judaism as it is currently practiced in certain circles has gone off the rails, how would we know? Is there some Archimedean point from which we could decide the matter? And if this is indeed the case, is the founding of a Jewish state likely to get us back on track? The answer to these questions, he writes in this article, I will attempt to show here, are all inextricably connected, and the key to finding them may perhaps lie in understanding Judaism as a language. Now, I am not going to share the rest of this article, but if there was a paragraph that I could say the entire 18Forty is developed as a continuation of this very question, it is that paragraph. The way that we think of our own Yiddishkeit and our own Judaism is learning how to make the case to ourselves and others, I think, in new ways that does not have to come at the exclusion or at the expense of our older, more essential stories, but it is giving new language to complement and give us greater conviction with that story as it is told. And when I think of Judaism as a language, I think first and foremost about authority.

There is nothing that gets Jews more worked up or more pearl-clutching when it comes to rabbinic authority. Who said? By whose authority? Who commanded me? Who said I have to do it this way? Who said your rabbi is right? Who said my rabbi is wrong? Who appointed you? All of these questions that Jews ask regardless of community are really important questions and they’re harder to answer based on an old methodology. But if you ask yourself, where does language get its authority from? Who said I have to speak English this way? Who said I need to talk this way? Who said I need to conjugate that way? The answer when it comes to evaluating the quality and efficacy of any language is based on the quality of what it allows you to communicate and who it allows you to communicate with. Wittgenstein, who was a philosopher of language that has had a real influence on me, would always say there is no such thing as a private language.

What we think in our hearts is not a language, that’s our own conscious process. Language begins when you are in dialogue with another. And what we need to remind ourselves is Judaism as language number one addresses the question of authority in many ways, and I believe this is true. I don’t speak English because I was commanded to speak English this way by the Merriam dictionary.

It may be that there are right and wrong ways to speak or to write, but the reason why I speak this way, the reason I write the way that I write is because who that language puts me in dialogue with, who it connects me to. When I think of how any community should be evaluating their own Jewish life and Jewish practice, I think it begins with Judaism as a language. And this removes some of the interdenominational competitiveness, the difficulty of anybody admitting wrong or right, the difficulty that people have even admitting any sort of hierarchical nature of better and worse when it comes to Jewish life, though I very much think there is better and worse when it comes to Jewish life, but we don’t like speaking that way. We know that it is harder to justify.

Why is it that we speak or write the way that we do? It is the community, it is the collective body of the Jewish people that transcends any one generation. That is who I want to communicate with. And even though in English I don’t speak the exact English of Shakespeare, it has certainly evolved over the last few centuries. The richer of a Jewish experience that we have, the richer our Jewish language becomes.

It communicates more broadly. And I think a lot of our woes in this moment is that we have had a breakdown in our common language. And so much of what I hope to accomplish on 18forty is recentering a common language of Judaism, a common language that regardless of your vantage point, how near or how close or wherever it is, we can all kind of listen in on a unifying point. We can all still have a shared conversation.

Now I am acutely aware that not all Jews speak English, and I do imagine a future where there is an 18Forty in Israel, it’s a dream of mine. I would love to set up an 18Forty, a Hebrew speaking 18Forty. I know exactly where it would go, what it would look like. Yes, this is why I fundraise and I’m not satisfied with 18Forty just as a podcast.

Yes, we need this, we need a common language where we have a place where Jews who most obviously disagree are able to be in dialogue with one another and be in dialogue not just about politics and the state of Israel, which are all important, and not just about anti-Semitism, but developing a common language for Yiddishkeit, so it is a more effective language, so it allows us to communicate more broadly and more widely with others. And that is how I evaluate and really urge everyone to evaluate their own Yiddishkeit. I don’t think every practice of Judaism is equally good or true, and that’s fine. That doesn’t mean that we can’t still work towards a common language.

I think I am an above average writer, that doesn’t mean that I can’t understand the writing or the text messaging from people who don’t have the same vocabulary as I do. I am still able to speak with them. And I think at the heart of what 18Forty is trying to accomplish and reintroduce to the Jewish people is this notion of Judaism as a language, to provide a new methodology for how we evaluate the quality of our own Jewish life and how to make the case for a Jewish life to others. I think we need a little bit of a different methodology.

I think we need a little bit of a shared methodology that allows us to even make the case for any strand of Judaism. Why do anything? It’s not enough to just say, well, Hashem said and then he told the rabbis this because then a person can, well, that’s not what my rabbi said. I have a different story. We need a shared methodology, and to me, the shared methodology to evaluate the quality of one’s Yiddishkeit is: who does it put you in communication with? And what is the experiential yield? What does your Yiddishkeit create? And most specifically the Yiddishkeit of your home.

I think the way that we evaluate the quality of our Judaism has drifted in the last 50 to 75 years to a very institutional model where we evaluate the quality of our Judaism in dialogue with the standards of any institution that we may be affiliated with. And there is certainly a place for that. But I think what we’re trying to accomplish on 18forty is develop a common shared Judaism, which is not that it’s uniform practice, but there is a uniform methodology that we’re all committed to evaluate our individual Judaism through a similar lens, which necessarily puts you in contact and in dialogue with Jews who think differently and do differently than you. But what it allows is a shared methodology that how I evaluate the quality of my Judaism is actually the same as how you’re going to evaluate the quality of your Judaism.

And how do I evaluate that? Based on the experiential yield, the same way you evaluate the quality of a language. Who does it put you in dialogue with? Does it allow you to be understood better and to understand their own story better? And I think the ultimate litmus test for anyone’s Judaism is the home. That’s why we are a religion that is founded by avot and imahot, by mothers and fathers. And the way that we should evaluate the quality of our Judaism is: what is the homelife that it yields? What happens? Is Judaism sufficiently felt and experienced? Is it overwhelming? Does it feel suffocating? Does it feel uplifting? I think we should judge the quality of our language based on how it transmits.

What does it say to the next person? How do they receive it? And while we can’t all speak to the entirety of the Jewish people, we can speak to our families. And that’s where I think it begins. And in every family, there is no exception to this rule, every family has different levels of observance, some who But the quality of our Yiddishkeit, the methodology with which we evaluate it, and I think we are creating a space that the ultimate goal that we are looking for is that common Judaism. What I think in many ways is the true and we’ll get to the end of it over here, but I want to like almost like take the mask off, this is why 18Forty in many ways was in that calendrical year and continues today to have Messianic aspirations.

This I understand is what is meant by Toras Mashiach. The Torah of Mashiach. What does that mean? We are told that there is a Torah, there is a religious system that will specifically be revealed in Messianic times. Yet we are also told that the commandments that we observe, the Jewish life as we know it is not going to change.

So how could we speak about this concept of a Torah of Mashiach? And I think in many ways this is what we’re beginning to realize and embrace. A Judaism that is fully justified and fully realized based on the experiential yield of the commitment itself. It’s where the ultimate reward of Judaism is your Jewish life. It is what Rav Tzadok writes in Tzidkat Hatzadik in the 41st paragraph, it is fairly radical but he says the reward for believing in God is the presence of God, is God himself.

Where the reward so to speak for our Judaism, for all these questions who’s right in the way to do it, the ultimate reward is the experiential yield of how uplifting, how transcendent, how inspiring, what Judaism does for our lives. What the Talmud in Tractate Berachot says and I’ll say it in the language of the Talmud and then of course I’ll translate. It says that the ultimate blessing that rabbis would give one another would be this line Olamecha tireh vechayecha. Olamecha tireh vechayecha.

That your world you should see your own world in your own lifetime. As referring to not a Judaism that is waiting for the next world to settle the scores and to finally either get your reward or your punishment for the neglect or the embrace of the Judaism that we have, but a Yiddishkeit that is fully felt, experience and uplifts us right here and right now. Olamecha tireh vechayecha. To fully see the product of our commitments, where the commitment itself is the reward, where the experiential yield of our religious lives is exactly what motivates our commitment.

That to me is redemption. That to me is a religious life that justifies itself. It’s not for something else, it’s not to get elsewhere, but it’s a Yiddishkeit like a language that right here gives you tools of communication to better experience and better enjoy life itself. So that is why I think these conversations are so important and that’s why I think the work that we do on 1840 is so important.

That I went with my friend Diana Fersko’s invitation, I went to speak and I’m not making the case necessarily for my Jewish life, but I am trying to make a case for Jewish life itself, for a common Judaism. We usually kind of stay within our own purview of our Jewish life, but I think it is specifically through dialoguing with others that we don’t normally dialogue with that actually increases the strength and the value of the language itself. I felt like a stronger and more committed Jew by being able to kind of articulate, though it was not in the classical way, but be able to articulate to others who hold on to a very different Jewish story, but be able to articulate to them what I felt was a shared language of Jewish life and Jewish practice. So it is without further ado and this very long but I think important introduction that I introduce our conversation with my friend Diana Fersko.

Diana Fersko: First of all, this is so exciting.

David Bashevkin: This is so lovely. I’m so happy to be here. Thank you so much for having me.

Thank you guys for coming out. I’m ready just to hang out with you, but to do it with friends and community, it’s great.

Diana Fersko: No, we got to be with the people. So I first want to take a minute to introduce this amazing person.

Don’t read my notes. To introduce this amazing person sitting next to me, Rabbi David Bashevkin. You have many jobs and many roles. You’re the director of education at NCSY.

That’s like the Orthodox version of Nifty or BBYO or USY, the youth movement. You’re the author of a book called Sin-a-gogue, S-I-N-a-gogue, which I highly, highly recommend. And you’re also the host of a really prominent podcast called 18Forty. Do you want to tell us just what 18Forty is really quickly?

David Bashevkin: Oh my gosh, I don’t want to lose them right up front, but we named our podcast podcast and media after the calendaric year of 1840, which is the beginning of the industrial revolution, but believe it or not, was also predicted in the Kabbalistic text known as the Zohar, because it’s the sixth century of the sixth millennia on the Hebrew calendar that people thought that there was going to be like a messianic upswelling.

So I named it after that in the hopes that we’re going through something similar, and the revelation of 1840 was really organic, bottom-up, like organic from the people rather than top-down. And I think we’re experiencing that now.

Diana Fersko: So, in addition to all those accolades, what Dovid really is, is like my friend.

David Bashevkin: Yeah.

Diana Fersko: And what we like to do is talk across differences with each other. We have some real differences, but we also have some real similarities and bonds, and I think we both find it very interesting to say like, “but how do you do this?” and “how do you think of that?” and that kind of thing. So we’re just going to have a free-ranging conversation, and I think Dovid agreed to maybe take like one or two questions at the end also, so think about what they might be.

So first, just tell us about you.

How did you grow up? How did you end up sort of where you are, being an Orthodox rabbi that’s also interested in a much broader Jewish world, and give us a little background.

David Bashevkin: So my family story is really the story of American Judaism in America. All four of my grandparents were American-born. My oldest grandfather was born in 1915, my grandmother was born in 1917, my Bubby was born in 1921, and my Zeidy, who was a World War II veteran, was born in 1920.

So it’s in that period that my grandparents were born, and my mother’s father, that’s my grandfather, did something very unusual in his family—it was in Springfield, New York—he said, “I want to become a rabbi.” So he went to Yeshiva, which was very uncommon in the 1920s to go to Yeshiva. He was the first graduating class of a Yeshiva movement that still exists today called Chafetz Chayim, named after a leader named Yisroel Kagan, and he became a rabbi. So my mother grew up in a very small community in Portland, Maine. He was the rabbi there for many, many years.

My father’s family—my father, grandfather, great-grandfather—all lived in what my Bubby affectionately called a crappy little town. That’s my—that’s my Bubby’s language, not mine. And that was in the Berkshires in a town called North Adams, Massachusetts. So North Adams, Massachusetts, is where, you know, the Bashevkins really ran that town for many, many years.

And my father was also the anomaly in his family in that he joined NCSY and decided to become Orthodox. He was Orthodox, but 1940s Orthodox, 1950s Orthodox—very different than the Orthodoxy we know today—and he decided to go to Yeshiva University. That was the big thing. So most Bashevkins are not Orthodox.

There are Bashevkins that live in Israel who are regular Israeli, secular Israelis, and most Bashevkins in America are—my father’s generation are Conservative, their children are Reform like my peers, and the ones younger we have less in touch because we’re spread around everywhere, but my first cousins who grew up in Bennington, Vermont, which is right outside of North Adams, Massachusetts, are Reconstructionists.

David Bashevkin: Okay. So we’re like all over the map denominationally.

Diana Fersko: Uh-huh.

And did you always just know you’re going to be a rabbi and live in the Orthodox world, or what?

David Bashevkin: No, I did not always know. I always knew I wanted to be an educator. I don’t even self-identify as a rabbi.

If I could give back my ordination, I would hand it right back.

I only completed ordination for my mother because she grew up in the home of a proper synagogue pulpit rabbi, and she said, “if you’re going to go around calling yourself rabbi, you have to finish ordination.” So I said, “Okay, Mom, I’ll finish ordination.” In the Orthodox world, having ordination is actually trickier. You have a lot more boundaries and structures. I’m not a congregational rabbi. I didn’t want to be a congregational rabbi because I would not be the kind of congregational rabbi that I would look up to.

So I didn’t want to run my own congregation. Instead, I love education. I love sharing ideas and education, and that’s how I got involved in NCSY.

That’s why I wrote that book, Sin-a-gogue, and I wrote a Hebrew book, I did a Haggadah, and now I have this podcast, which is one of the largest—it’s 50-50 Orthodox, non-Orthodox are listeners—but it’s one of the largest Jewish podcasts out there, and the joy of it, I look at it as Jewish education. We’re not an Israel advocacy podcast. We’re not—we don’t fight antisemitism. We educate about Judaism.

That’s what we’re all about.

Diana Fersko: You know, I’ve listened to it many times and it’s really amazing because it’s like, for me, a window into what feels like almost a different universe. There’s lots of vocabulary that I don’t use, or some of it I don’t even know. There are problems and I don’t even think about, you know, it’s a cultural lens into what’s happening in the Orthodox world.

David Bashevkin: And we try to translate. but it’s so hard to even remember because language is so cultural, so I really do my absolute best and I’m very proud of the fact that I have been criticized by our Orthodox listeners for translating so much. They say “Wait, what are you translating all these words for?” I say “No, no, you’re not the only people in the world. There are other Jews out there we’re trying to reach and we try to open it up as much as possible, but I still sometimes use the language just to be a window into that flavor of speech.”

Diana Fersko: Absolutely.

I mean you’re also conveying a sense of Yiddishkeit.

David Bashevkin: Exactly. And I use the word Yiddishkeit over, that’s what I like. I like Yiddishkeit.

It feels less like a political party than Judaism. Yiddishkeit feels warmer, homier.

Diana Fersko: Chewy. Yeah, exactly.

I like that. So here you are at a Reform synagogue and you might be the first Orthodox rabbi to speak at our synagogue. So thank you for being here. It’s a privilege.

What do you want the liberal Jewish world to know about Orthodoxy? Maybe there are some assumptions that we might have that are false or stereotypes, preconceived notions, or maybe it’s just something that’s part of the character of Orthodox Judaism.

David Bashevkin: I think first and foremost it’s really important to know what is the role of any denominational affiliation. Denominational affiliations are so recent in terms of the wider lens of Jewish history that I think it’s important to reemphasize over and over there is no denomination that has an exclusive ownership over Yiddishkeit and Judaism. But I do believe that there are things that every denomination can learn from one another.

I think in the Orthodox world I wish there were more notes taken and I would point out three things of a cultural notes that are taken that I think should be paid attention and should not be affiliated with Orthodoxy. They should be affiliated with Judaism. And those three things that I would say are number one, the emphasis on lifelong education. We are a very highly educated community.

I think the biggest barrier unfortunately right now, I’m talking in generalities between your average Orthodox Jew and your average Reform Jew, it is not about practice; it is simply about the basis of knowledge. The Orthodox community came at a crossroads in the 1950s. This was even after my parents all went to public school, but they realized that Jewish education is not in order to train rabbis, which is what my Zaydie thought. When my father said “I want to go to Yeshiva University,” my Zaydie was like “What, to become a rabbi? I thought you wanted to be a doctor.” My dad’s like “Yeah, I want to be a doctor, but I want to also be educated and deeply educated.” So the education is really lifelong and if you walk into any synagogue or Beit Midrash in the Orthodox world, you really see this hunger for knowledge.

I think sometimes the motivations could be sometimes less pure. There are people who you feel an ego, “I’m so impressed, I’m scholarly.” But in the culture there’s really a sense of lifelong learning. That’s number one. I’m almost saying the things that I wish were decoupled from Orthodoxy.

Number two is a consistent communal public Shabbos observance where Shabbos is able to be felt in the home without any, you don’t need a calendar. You can feel Shabbos in the home. And I do understand that different relationships to Jewish law and halacha are going to yield different experiences.

Diana Fersko: We’ll get into that.

David Bashevkin: Exactly. But I do think that, especially now in this moment when there’s such an encroachment on technology, when you’re reading about unplugging in your average New York Times, I think every week there’s an article in the New York Times “How do we unplug from our phones?” and there’s a part of me that wants to raise their hand very gently and very humbly and say “I’m not saying I or any community has all the answers, but it’s worth looking at that we have a community of professionals, of public people live in the modern world, have real jobs, and they’re able to sustain public Shabbos observance.” The last and final thing, and this is the thing that I think wraps everything together, and the Reform movement I think has done a lot recently to change this, but that is deep immersive culture, Jewish culture for children. I think the mistake that everyone makes is they talk to grown-ups and grown-ups are making their own, they have opinions and choices. I think that your affinity and your connection to Yiddishkeit in the formative years, I would say from the age of like three to ten, that’s the time where I think you learn the rhythm and the cadence of Yiddishkeit.

And what I think the Orthodox community, and I’m actually going to single out not my community but the Chasidic community, what they have shown the world is that if you want to sustain deep immersive culture and really connect to Yiddishkeit, excited, you need to invest in young children. They’re not the ones who get the most sophisticated ideas, but I have a three-year-old. My three-year-old like any three-year-old old on a Friday is watching Peppa the Pig like everyone else. Trust me as an Orthodox rabbi, it gave me no joy when my three-year-old son started referring to me as Daddy Pig.

So that is definitely not, definitely not the goal here.

Diana Fersko: Over the line.

David Bashevkin: Yes, that’s it. But he does.

But every Friday we turn off the television, and he cries like any other three-year-old. But then he also knows that when Shabbos starts we put out Shabbos treats and he gets excited. So we’re already educating him to something that he knows the joy, and when he’s frustrated about Shabbos—I have a nine-year-old son—when he’s frustrated and, you know, like any kid, “I want to be on my iPad, I want to be—” I said, “If you were on your iPad, what would I be doing? You’d be in your office working on your computer. I wouldn’t be out here on the couch in the living room reading a magazine, reading a book, and we’re all here together.” So I think a lot of the deep work in terms of your affinity and your connection to Yiddishkeit is happening at an age where all the communal resources—we like talking to grown-ups, they’re sophisticated, they’re smart—and I think what they’ve done really well is the camping, the experiential component of Yiddishkeit and bringing young children in.

Those are the three notes. I don’t believe that everyone can or should be Orthodox. I don’t think that it’s possible. Not everyone is fully Orthodox within the Orthodox community.

What I do think is that everyone should take the lessons of what are the ingredients that sustain lifelong, healthy Jewish connection. There’s what to learn from everyone and I would highlight those three: education, Shabbos, and youth programming within the Orthodox world.

Diana Fersko: You mentioned the word “obligation,” and I want to talk about that a little bit. Halacha, Jewish law.

What gives you that sense of obligation? I’m asking this because in our world, in a Reform universe, we have a phrase which is, “Halacha has a vote, not a veto.” Okay. Meaning like, it’s part of—Jewish law is part of how we make Jewish decisions, but it doesn’t obligate us. And that’s a very heavy sentence to say, actually, in a lot of ways. But the reason we do things often is because of personal meaning.

So I light Shabbos candles because it makes me feel closer to God. Or I light Shabbos candles because my grandmother did that and that’s important to me. Or because I see it’s part of like a communal behavior. But it’s not because God told me to, and it’s not because it’s been written down in, you know, codes.

Talk to us a little bit about how you perceive the role of obligation in your life, because I think that’s an interesting difference between communities.

David Bashevkin: It’s a really interesting difference and here’s the nice part is that I too, like yourself, have not heard God’s explicit command. He has not come to me in a dream, I have not had any prophecy. I read the Torah and the book what we say is the word of God, but even in the Torah there are a lot of ways to interpret that.

I would say two things. Number one, I don’t like the word “obligation.” I do like the notion of “commandedness.” Commandedness is really just the only byproduct. When God reveals himself to the Jewish people in the way the Torah gives it over, God does not reveal himself as a commandment. You know, the first—you could see up there, you have it right over there on the tablets, right? The first commandment is Anochi Hashem, which is, “I am your God.” God does not say, “I should be your God” or “make me your God,” it’s just like an introduction with no commandedness.

I believe that it’s not about obligation, it is about feeling that there is something beyond myself. It’s stepping out from a purely materialistic view and saying that there is purpose to life and to the world. That is where I look at commandedness. Commandedness means the world has a purpose, my life has a purpose.

Now how to find that purpose and how—that’s all afterthought. But to me it’s not about obligation, I don’t feel obligated by rabbis, I don’t keep Shabbos because my rabbi told me, I don’t keep Shabbos because I’m going to disappoint my mother, I keep Shabbos because in my life, the way that I find purpose and the way we create purpose, that’s where I feel commandedness, like I need it. I need that experience. I want to talk about just Jewish law.

I don’t even like the term “Jewish law.” The Hebrew term is not “Jewish law.” We use the term Halacha, which is about movement. Halacha is deliberately—means to holech, means to walk and to go. My understanding of Jewish law is, number one, is I look at Halacha much more as a language than a legal system. Halacha is a language.

Language is meant to transmit something. There is a way to speak very properly, you could sometimes speak more with a slang, sometimes you have people who cannot understand the language at all. Halacha is a language to bring divinity into your life. There is the codes as I would say that is the equivalent of like reading the IKEA instruction book.

That’s like the very perfect way to do that. I have not met an Orthodox Jew who lives their life according to the codes, according to any—you would be a stilted robot, there would be no rhythm to your life, you wouldn’t be able to move and Halacha… versus the way that you text versus the way that you write in email or you write a formal letter. I look at this when I read the codes, I’m looking at Shabbos in the pristine IKEA, this is what it means.

And you need that the same way we need a dictionary, the same way that you need grammar. But I also believe that grammar can be too restrictive. If you’re not able to speak, the grammar’s not working for you. You need the language that is actually able to transmit something.

What Halacha is trying to do, it is a language that is meant to preserve experience. What is the experience? It is the reminder of God and the Jewish people. That’s what Halacha is reminding us that there is a God, connecting us to the entirety of the Jewish people. And Wittgenstein says this, Wittgenstein was a philosopher of language, Wittgenstein says there’s no such thing as a private language.

You can’t invent a language with nobody to communicate to, that’s not a language. The function of a language is that other people speak it. The reason why I think the Orthodox community has done well is yes, they couch a lot of it in divine language, but I don’t think that’s what gets the community going. It’s not that you meet an Orthodox Jew and they’re like oh my gosh, a thunderbolt’s going to come out and strike me down and strike me dead.

I think what works is the fact that everyone realizes that to sustain rich language, we need a lot of people participating, which builds the language and builds the ideas. And that’s kind of how I look at the way Halacha, Jewish law, is in the Orthodox world. But I want to just say one other thing and I think this is really important, it may sound controversial, especially coming from an Orthodox rabbi. I don’t believe in rabbinic authority.

We usually think of rabbinic authority, the rabbis have authority over us and what we’re really arguing about is what level do we give of rabbinic authority? I don’t believe in rabbinic authority. The only authority that we have is communal authority. Communities endow authority into a certain way of life. What invests authority into any practice in Jewish life is about the lived body and community of the Jewish people.

So in the Orthodox community, I don’t think the main difference is the rabbinic authority, I think it’s the communal authority. That when you go into an Orthodox community, it is so communally aligned and there is this public way that we conduct ourselves. It makes the language much more rich. It also can be more rigid for some, it’s not sustainable.

But the goal is that every community should develop a language, a rich language that’s an insider language. That’s a good thing. To me, if you have a community that’s for everybody, it’s for nobody. You need to develop a unique language for your community that sustains Jewish practice.

There are some communities that it is too much for a lot of people, it becomes suffocating. And there are some communities that it’s not enough, people walk through and they said, I never got the sweetness and the richness of anything. And I think what everyone is trying to figure out regardless of denomination is basically where their personal supply and demand curve yield. There is supply and that is kind of the community that is giving you programming and teachings, and then there’s the demand, what’s my capacity, what do I need? There are some people who their supply and demand curve don’t meet each other.

I need much more than I’m getting, and there are some people who are getting much more than they need. The key is finding a community where you feel I feel inspired, I feel purposeful in my life, I feel like there’s a real sense of being Jewish that I can hand over organically. Not even hand over, it’s through the mimetic tradition, just it’s in the air, it’s in the culture. I think that’s the way Judaism has survived.

And to me, that is about shifting our minds of a legal rulebook and thinking about how fluently do we speak Jewish?

Diana Fersko: Aha. So let’s keep going with your metaphor then. Speaking of languages, sometimes there’s a language barrier between our two communities. Very much so.

And I feel like I’m going to throw out some stereotypes or things I’ve heard in the past. I’m not asking you to speak for Orthodox Judaism, just give me your sort of take on it. I feel a lot of people in our, not our community specifically but our community broadly, feel very judged by Orthodoxy. And there’s a feeling of you probably do know a lot more about Judaism than we do, about Jewish text, for example, than we do, and you’re kind of in the more end of things, more observant, more strict, more committed in some ways.

And that can feel very judgmental and like there’s a looking down on non-Orthodox Jews. And I’m wondering if you could comment on that? Have you found that to be true? And sort of the sub-question in there is about denominationalism. Do you think it’s hurting us in some ways? What are the hurdles that have sort of evolved? Because I do think it’s like actually pretty painful if you think about the landscape of the Jewish people right now. There’s lots of fracture.

It’s heartbreaking. It’s worse than painful. Yeah. And what even just a little bit of healing.

So just talk to us a little bit about, do you think any of those feelings are true?

David Bashevkin: Let’s start with the judgmentalism. Yes, of course, undoubtedly it’s true, and there’s a part of it that I look at and understand, and there’s a part of it that I look at and criticize very deeply and very vocally. The part that I understand is what I mentioned before, and that is the educational background divide, the language barrier. It is different.

You could have an eleventh grader who is in a Yeshiva high school who is already kind of comfortable reading Talmud and comfortable reading Mishna. And when they look at somebody who did not have the same educational background that they have, I understand, I think it’s immature, but I understand why they look at themselves as being superior. That I look at as extremely tragic, and I look at it as tragic because they would judge my Bubbie and my grandmother the same way. It is what I call an unearned sense of superiority, meaning you have to know how you got here.

My grandmother, who was married to the rabbi, my grandmother was not able to read Hebrew. She never went to Yeshiva. If you were born as a woman in 1917, your parents didn’t necessarily send you to the same Hebrew opportunities that the men got. So my grandmother never learned how to read Hebrew.

She could not make, at the end of what you say grace, like we bentch after meals, which a lot of kids of all denominations learn the song after camp, Baruch Ata, and she never knew how to do it. She never knew how to do it, and it was deeply embarrassing for her to be a Rebbetzin in the community and not be able to read a lick of Hebrew. And I think of my Bubbie and my grandmother, and I also think of my Zaydie. My Zaydie did not keep Shabbos.

He began keeping Shabbos when he retired. And I think of the sacrifices that they made for their life, and I tell my students this, my Bubbie used to drive an hour to Albany to Price Chopper to buy kosher meat. That’s the one thing that she did. She would drive an hour to buy kosher meat.

I tell my students, what’s the most you’ve ever done to keep kosher or do anything? Have you ever driven an hour regularly? Most kids have not. That to me is the unearned sense of superiority. You can have a sense of appreciation for the educational opportunities you were given, but you need to appreciate that they were given to you. A lot of the entitlement, you were born into it.

The second thing I would say is the triumphalism.

Diana Fersko: Because Orthodoxy is having a bit of a moment, right? There’s a lot of triumphalism right now.

David Bashevkin: Yes. I have written about this explicitly.

The triumphalism of our community to me, I understand it because there were so many years where we were on the other end. If you reverse the clock to the 1950s and you read the writings, there was a sociologist affiliated with the Conservative movement named Marshall Sklare. Marshall Sklare wrote a series of books basically saying in America, Orthodoxy is obviously going to die, like it’s ridiculous, the Reform is not strong enough to survive, and Conservative is the future. If you look at the landscape now, that is not how anything is shaping up.

When I think about the triumphalism, it’s so laughable because whatever you think of the landscape of the Jewish community, it happened under all of our watch. I don’t like the landscape of the Jewish community either. I look around and I’m not in love with the American Jewish community. I do see a lot that could use improvement.

But I don’t blame, it’s my fault too. I was also around. I’m also a Jewish leader. The problem is is that we gerrymander our boundaries.

If I gerrymander my boundaries and say, well, I’m only in charge of the people who are succeeding and everybody else is a total failure, then sure, you’re able to be triumphant, but that’s unfair. I don’t like that. I think that we have to take responsibility. The landscape of the Jewish world is all of our responsibility.

I think instead of triumphalism, I do appreciate Orthodoxy’s pride and confidence in what it’s doing. I think everyone should have a sense of pride and confidence in what they’re doing, but it should not be denominational, it should be familial. Your Jewish home, you should feel confident in your Jewish home. Not to impress your rabbi, not to impress your parents.

The litmus test of whether or not am I doing Judaism correctly, the litmus test is the next generation. The litmus test is the feeling in the home. The litmus test is how you get along with family members, with your spouse, with your children. That to me is the ultimate what we’re trying to create.

I remind people over and over again, Judaism was not founded by rabbis, Judaism was not founded by prophets, Judaism was founded by Avos and Imahos, mothers and fathers. We are a very family-based religion. And what I hope is that anyone’s sense of triumphalism should be directed at their own home. If we took a real sense of agency and responsibility in the homes that we are creating, I think we would all be much better off.

I want to start a new. But I’ve often said that each denomination contributes to a different unit of Jewish life.

Individually, I’m first going to say it and then I’ll explain. Individually, I believe we’re all reform Jews.

Familially, we’re all conservative. And institutionally, we’re all orthodox. I want to explain what I mean by that. I’m talking about the methodology.

What’s the methodology of the Reform movement? You said it yourself, it’s what resonates on a personal level. On an individual level, when I’m in the bathroom and deciding whether or not I should tear toilet paper on Shabbos or do whatever, the only thing stopping me or not stopping me is my personal choice. You know, my personal sense of commandedness or ethics or belief. The same as you.

When I’m alone, I’m a reform Jew, not in my practice, but in my methodology. What do I really believe to be true? On a familial level, I think we’re all kind of the same as conservative, which is we want the tradition, we realize that, look, you have to cater to your family, you have to kind of soften the edges a little bit to make sure. The reform movement is much more like what’s talked about as catholic Israel. What’s done? What’s normal? I think when you raise your children, you have to make sure you’re raising them in an environment in your home, it’s normal.

They’re in an environment where they see themselves and their own Jewish practice as aligned with their life and community. That’s a very conservative outlook. Catholic Israel. Not catholic like catholicism, catholic like universal Israel.

That was the methodology associated with Solomon Schechter. The orthodox movement is really all about what is the ideal standard. What is a standard? And the reason why I say all institutions are orthodox is because every institution needs a standard. You don’t come into this synagogue and it’s like, you know, you could use our siddur, you could bring in your own siddur, you could bring in the New Testament, you could bring in poetry.

Like, there’s gotta be a unifying text. Every institution has rules, every institution has expectations. And I think on the communal level, we’re all using the methodology of the orthodox movement, which is we need to just figure out, like, what’s the standard. And we need a standard that can unify the community.

Too much individuality is going to disrupt, you’re not going to be able to have that communal feel. There’s no such thing as a private language. So every community is trying to figure out what’s the standard that works for them. So I really do believe that every denomination is contributing methodologically to Jewish life.

There’s no question about it. And not just methodologically, I think if you look at the last hundred years, even in practices, even in the orthodox world, so much has trickled in from the reform world. They don’t necessarily know it, but you think of bat mitzvah practices, you think of the havdalah service. Debbie Friedman, right? That was, we love that.

And even in the initial reform sense, which was Judaism at the end of the day is always going to come down to personal choice, is true in the orthodox world, it’s true in the reform world. We have the separation of church and state that happened in the 18th and 19th century. We no longer coerce religion. This was Moses Mendelssohn’s great contribution in Jerusalem.

I agree with Moses Mendelssohn, you cannot coerce religion in the modern world. So we’re all kind of left with the same question: how do we use our soft powers of influence to help people find the right standard for themselves? And what I think the main unit that we should be focused on are families.

Diana Fersko: Okay, three things. One, like your bubby, my mother also drives far distances for kosher meat.

And I feel obligated to tell you that. So she lives on the west coast of Florida. She will drive to the east coast of Florida to get the right kosher meat. She will drive home.

She will make the brisket. She will freeze the brisket. She will fly north with the frozen brisket on the plane. There we go.

Two, last week I was at a conference with other rabbis.

It was on viewpoint diversity. And one of the questions was the synagogue is the most important institution in Jewish life. And most people agreed, but two of us disagreed and we said the family is the most important institution in Jewish life. The home.

And I think we convinced, you know, some others to come with us. But what’s interesting is that part of the feedback was from like a lot of the very liberal rabbis because this was like across the denominational spectrum. You know, a lot’s been lost in the Jewish home. Yep.

It’s not so easy. People are understandably overwhelmed or confused or like, oh, yes, of course there’s YouTube, but now I have 5,000 YouTube videos. Like, which one is right? How do I do it? And am I doing it right? You know, there’s a great deal of discomfort in a lot of Jewish homes, which I understand a lot about how things became that way. So I think that’s like part of the repair.

David Bashevkin: Oh, it’s 100% the repair. And it’s so funny that I also grew up that the importance of synagogue and the beit midrash and institutions. I think institutions are good, but they’re like cruise ships. It’s very hard to steer a cruise ship.

That’s like the big federations, legacy organizations, and even synagogues. To move a cruise ship even an inch can take an hour.

Much easier, you got four people in there and you’re able to respond to their emotional needs, their intellectual needs in a much more customized way, so my litmus test is my spouse and my children.

If you ask me am I a good Jew or not a good Jew, my answer is you have to ask my wife and my children. They know, they see me and what I’m able to create together, that’s the yiddishkeit that I put out in the world and I trust the most.

The thing that I say is synagogues are modeled after the temple in Jerusalem. The temple in Jerusalem if you look at it is modeled after a home.

It has like a kitchen area, it had a kitchen area, it had the altar, it had a place where they had the loaves of bread, then you step in, then there is literally the Holy of Holies is modeled like a bedroom. That was the place of intimacy, divine intimacy. And if you were to ask me where is the Holy of Holies of Jewish life, it’s in the places of intimacy between husband and wife, between families, where you really create a space where there is no one coercing and our yiddishkeit is us. We’re in this together and that gets to the ultimate building block of Jewish life, which is family.

Diana Fersko: That’s so beautiful. So something that I’ve always admired about you is your deep knowledge of Jewish texts. And I don’t know how you feel, I always feel like I always want more and I’m always learning more. So I don’t want to put you on the spot but I’m going to put you on the spot because I know you can do this.

Would you be willing to share with us maybe a piece of text that inspires you, whether it’s aggadah or something from Torah, something that you feel like is an animating force to your life?

David Bashevkin: Yeah of course I would love to, there are so many. There’s a story in tractate Taanit on the very bottom of 20a if you look it up, is a really remarkable story and it gets back to this triumphalism. The story is told of a rabbi who is coming back from yeshiva, literally, it says coming back from yeshiva and he’s feeling very proud of himself, feeling a little bit of an ego trip. I felt the same thing when I came back from yeshiva, I came home, I just looked at, you’re doing it wrong, you’re doing it wrong, you’re doing it wrong, you feel and he bumps into somebody, this is what the Talmud says, he bumps into somebody and he says wow it is remarkable how ugly you are.

You are so ugly. And he asks him by chance is everyone where you’re from this ugly? Real story. And the person gets very offended and he says go ask my maker, go ask God, he made me, I’m not, so then he realizes oh I offended him, I didn’t realize I just was trying, I’m just asking questions here, I didn’t realize. He just was that ugly.

So then he starts, please forgive me, I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean, I didn’t mean to offend you and he chases him until this person who just came back to yeshiva finally comes to the steps of his own community where his students go out to greet him. And this guy who’s offended sees all of his students and says you know what I wasn’t going to forgive you, I’m going to forgive you on behalf of your students, but just don’t do that ever again. And the rabbi said thank you so much and he set a teaching at that moment.

He said you should be soft like a reed and don’t be rigid like a cedar. Be soft, rach, which is soft like a reed, if you ever see a reed like it sways in the wind, it’s a very loose and don’t be tough like a cedar and that’s why he says when we write our Sefer Torah, what’s in the ark, we always use a reed, we do not use cedar tree to write it. Now this story has moved me for two reasons. It’s always moved me on a personal level because my hair started turning white when I was 16 years old and people would literally go up to me and not actually say wow you’re so ugly but by people literally walk up to me be like hey you know your hair’s turning white and I’d be like thank you so much for letting me know, I had no idea, thank you, thank you for letting me know, I’m a 12th grader in high school, so that was very painful.

But there’s something deeper that’s going on in this passage and that is the rigidity and the unearned superiority that each of us feel in our own lives when we accomplish something and then we look at others who haven’t had the same opportunities and we see ugliness, ugliness not in a literal way, but we look at them as spiritually ugly. The Talmud is criticizing that. The Talmud is saying just because you had an opportunity and you feel this sense of accomplishment and scholarship, be proud of your accomplishment, be proud of your scholarship, that does not give you a license to look at others and call them ugly because God creates people with different spiritual capacities. Not everyone has the same spiritual capacity, not everyone’s going to be a scholar, not everyone’s going to be nitty-gritty and be able to do the law ever so carefully, not everybody’s going to have Shabbat the way that you think is so beautiful.

And the key is not to look at others and call them ugly. And what the Talmud is really saying when we look at our own story and when we write our own story, when we write that Sefer Torah, which is not just the literal Sefer Torah, when we think about our own lives, we need to write it with a certain resilience, with a certain flexibility to realize that just because what worked for you, the rigidity of a cedar is not going to be able to contain your story. If you want to transmit a story, it has to be written with the flexibility of a reed that is able to sway, has slack in it. If you have that rigidity that is only my way, that’s not going to be able to transmit and you’re going to end up looking at the rest of the world and ultimately yourself as being ugly.

And that passage, that story is something that communally I see in all directions. I think there are so many misconceptions. We like to feel a sense of unearned accomplishment. We like to talk about our locus of control when things go right and when things go wrong in our life, we blame our parents and our colleagues and our boss.

The issue is we have to realize that we have to be more consistent and realize that we have our own limitations that we may never be able to break out of and other people have their limitations and so long as that we’re respectful of one another’s capacity, limitations and we’re able to create a shared language that is freeing, that is able to lift and connect to all Jews, that gives us the window to look and see the beauty in one another. And that’s really what that story of Taanit is talking about. I feel that tonight of being able to look at one another and see like look, there’s a beauty everywhere and yes, you could get caught and lost in your own rigidity, but we have to write our story with that flexibility.

Diana Fersko: First of all, that’s so beautiful.

Thank you for sharing that teaching with us. I also love that story. And one of the reasons that I love it is because do they name him? Shimon, is it? Do they name the first guy or no?

David Bashevkin: Yeah, I think it’s Rebbe Elazar bar Rebbe Shimon. I think so.

Diana Fersko: I can’t remember. But the first guy who’s coming down from the Migdal and

David Bashevkin:He’s the one that’s named. The ugly person’s not named.

Diana Fersko: The first guy.

He’s calling this guy ugly, but actually he’s having a moment of true ugliness himself.

David Bashevkin: Exactly. And then what’s interesting is that the person who’s criticized as ugly, he becomes stubborn like a cedar.

He doesn’t want to forgive him. He gets lost in his rigidity. Rigidity begets more rigidity and flexibility, understanding, compassion and empathy is going to beget a world with more compassion, empathy and understanding.

Diana Fersko: Amen.

May it be so. Amen. Thank you so much. Would you take a couple?

Question: Jewish Action Committee here at the Village Temple and I pose this question as somebody who’s recently gone to Poland to kind of reconnect with my ancestors and also as somebody who feels really, you know, this spirit of Tikkun Olam which I think very maybe outsiders know Reform Jews as like oh the Tikkun Olam people. But I really struggle and think about ways and in the world right now I feel so upset about the amount of division within the Jewish community. And so I share this just to ask you, you know, what are your ideas on ways that we can unite as Jews?

David Bashevkin: What an absolutely awesome question. It’s very hard when we talk about Jewish unity because we love it as a concept and then when it comes down to then you’re actually interacting, things like break apart.

Though every Jew be like unity we love, we love unity but the problem is when every Jew thinks of unity and closes their eyes, they just think of a lot of people who look like them all coming together. I think that this moment allows for a certain non-hierarchical conversation where we could learn to pay attention to our triggers and why we actually don’t like some Jews. I think that if we had more exposure just for like basic kindness and Chesed. I think that you find Jewish unity in one place and that’s in hospitals.

And I’m not just talking about in tragic times, I’m also talking about in birth wards, delivery rooms, you see that we’re working towards a common purpose and there’s so much kindness that happens there. When my daughter was first born, she struck a fever and she needed to go to the emergency room and I remember walking in, there’s a closet in most hospitals in New York have this that have kosher food in case you get stuck there overnight. And I remember I walked in there and I started to cry a little bit. These rooms are housed, staffed and paid for by Satmar Chasidim.

I’m not Satmar, I have nothing to do with that. I think when it comes to kindness and helping others, not helping me, going outwards and saying let’s join together not to help you or me but to help the third person, that’s where you see the real beauty of how Chesed, how kindness and acts of giving is the ultimate unifier because then we both step out of our biases and out of our differences and we focus on elsewhere. It’s almost like if you’ve ever been in a negative rumination spiral. I mean, I’m an anxious ruminator.

The way that I break out of those spirals is I need to focus on somebody else. You get so self-obsessed. I think number one is finding shared Chesed, rebuilding cemeteries, soup kitchens, all of this stuff is so holy and so many people would be willing to participate and there’s also you don’t get the educational differences because we’re helping the third person. It’s not who’s smarter, who knows more.

The other thing is I think we have to be more honest and paying attention to our individual baggage. There are Jews I don’t like and trigger me so to speak or make me feel inadequate or inferior. What I started to do is instead of immediately trusting my intuition, I think of a Torah that was said by the Baal Shem Tov who was the founder of the Chasidic movement. The Baal Shem Tov has this very beautiful read of a line in the Mishna where the Mishna says any blemish you’re able to see and identify like an impurity, a blemish that gives impurity, you can see anyone’s except your own.

Now most people read that as a cautionary tale about biases. The Baal Shem Tov reads it differently. He says any blemish that you see outside is really coming from something inside. It’s deriving from yourself.

It’s a very profound teaching because number one, it places the source of revelation inside. In here. There’s revelation happening here. And number two, it allows you to say, whenever I see an Orthodox Jew, I feel inferior in my Jewish education.

It allows you to stop and say what’s going on inside? Are you? Is that something that you’re struggling with? Meaning don’t always blame it on the outsider. Use those interactions to ask yourself what is this bringing up? I think about that concept with my own students. I teach in Yeshiva University and very often I walk in and there’s just one or two kids in the class who are like, I do not like, we’re not syncing, we’re not this. And I started to pay attention to my feelings.

Does she remind me of someone, a relative, a parent, an old bully, or whatever it is? And when you pay attention to that, you realize that a lot of the negativity we can take ownership of and we can kind of strip it away from the person and the reality that we’re interacting with. So I think those two things are helpful as practical aspects.

Question: I guess I would just also request if I can just add on, to think of us. In your work with the teens and your students, if we can partner with our students and we can get some cross-pollination going and learning from each other or just simply getting to know one another.

David Bashevkin: A thousand percent. Yeah. Yes, yes. Yasher koach.

Question: Last week a man that I know who belongs to a Conservative synagogue on the Upper West Side asked us to tune into a Zoom on Saturday. He was introducing a woman in his temple who was going to be honored because she had taken on so many roles and helped so many. And she started to speak and within five minutes I was offended by her.

She was sneering at us and it came across. She said, I went to a Reform synagogue with my friend and I was surprised that there wasn’t a sign on the door that said closed for Shabbat. That’s sneering. I don’t know who that woman is.

It wasn’t me. But she spoke beautifully. And then this came out and I found it very offensive.

David Bashevkin: Yeah, I think a lot of the denominational tension and sneering and superiority has unfortunately been…

October 7th and what’s going on in Israel has basically been kerosene and gasoline on our differences in that area and learning how to find language and build relationships that are strong enough to carry our differences is really important. What I basically found is like, you know you have friendships that like you’re not such good friends. So you’re camp friends. You went to camp together.

So if something difficult happens or you get into a disagreement, I hated that movie, I loved that movie, you’re like, you know what, forget about it. I don’t need you. The problem that I found communally of where we are in the United States of America in this moment is we don’t have a strong enough basis to actually shoulder these cosmic questions that are now being thrown our way daily. I mean, the Jewish people have been in the headlines uninterrupted for two years and it does not look like it is stopping.

It’s happening on all political sides and everywhere and I think that a lot of the frustration and the blame unfortunately is people pointing to denomination. It’s your fault, it’s their fault, it’s their fault. I don’t like that. If you’re going to blame anyone, I like just blaming nameless Jewish philanthropists who I think have just invested in all the wrong things.

I’m not pointing at anybody specifically. A lot of those investments just didn’t flourish so much. But I do think that before we navigate our differences, we have to have a strong enough foundation that can shoulder these cosmic differences. I remember I heard a rabbi talk about their son coming out as gay.

An Orthodox Rabbi who in the community that that could be tough on him, it could be tough on any family, you know, when you’re raising a kid. And he said something that to me was very profound. He said, make sure the first time you say I love you to your child is not after they come out to you. You know, that you do that big, make sure that’s not the first time.

Of course you’re supposed to say I love you afterwards, I love you no matter what and you’re my child and I’m with you and of course. But that can’t be the first time. And the problem is we as a community have not really been saying I love you to one another all that much. So when this really difficult and divisive issue comes up, which is splitting all communities—Orthodox, Conservative, Reform—what’s the vision for the state of Israel? What’s the vision in this moment? What’s the vision for the Jewish people? We don’t have the foundation that is strong enough to shoulder the intensity of these divisions.

So I think we need to almost like kind of build the airplane while we’re in the air, but we need to focus on building a foundation of just common understanding, which is like this is how you do it.

Diana Fersko: Right, I also think it is very much from the people that this change is going to come, because what’s happening is our divisions are very real, but they’re also very much highlighted in public, you know, and it’s very much leader versus leader, and institution versus institution, and, you know, denomination versus denomination. But the truth is, when you get ten teens in a room, it just doesn’t matter.

When you get ten people that are willing to fulfill a certain mitzvah to do some chesed together, like, that’s the work of the future, but it’s on us to be much more intentional about making those opportunities and crossing those bridges.

David Bashevkin: And building the foundation before we like step into the most cosmically divisive conversation.

Diana Fersko: Too late, but it shouldn’t be the first, yeah.

Question: I kind of have a question and you sort of circled around the beginning and then you’re back to it and I’m not sure where it fits in, but I am interested in institutional Jewry and I think it has failed the moment. I don’t quite see how this emphasis on family, which I get because we can control it, somehow is going to build community to take on who we are as a big community to meet this moment and I’m having trouble with those connections. I also have a hobby horse about the failure of institutional Jewry. And I also disagree with you about adult education.

I think we’re woefully uneducated and the kids are educated, but I don’t see us as an adult why I have access to the kind of strong adult ed. We had a Kollel out here in the village which met most of our needs and that was destroyed by institutional Jewry, by the way.

David Bashevkin: Yeah, we need adult ed and I’m super pro-adult education. I just think we don’t want to get lost.