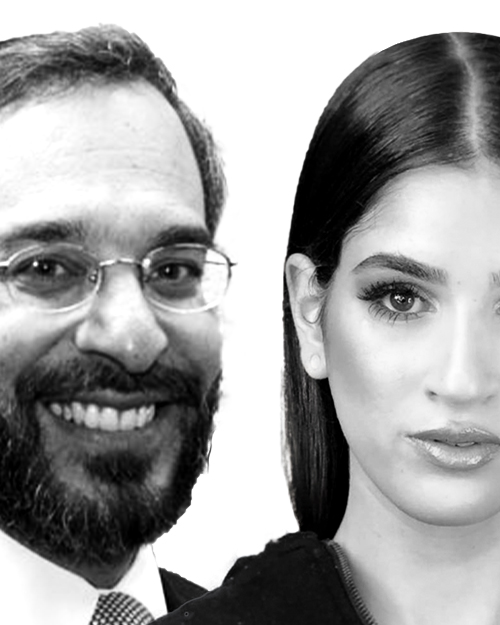

Shani Taragin: ‘It’s good that Judaism is hard’

Rabbanit Shani Taragin answers 18 questions on Jewish mysticism, including free will, prayer, and catharsis.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

Whether through the lens of Tanach or Maimonides, Rabbi Kook or the Zohar, Rabbanit Shani Taragin believes that the layers of the Torah form a unified language of divine intimacy.

Shani directs and teaches in Israel and worldwide. She currently serves on the advisory committee for the Mizrachi Olami Shalhevet program, as Rosh Beit Midrash for the women in Yeshiva University’s new academic program in Israel, and together with her husband, Reuven, as Educational Director for Mizrachi Olami.

Today, she joins us to answer eighteen questions on Jewish mysticism with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy including teshuva and free will, the significance of the State of Israel, and prayer as both worship and catharsis.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Shani Taragin, it’s a privilege and pleasure to be sitting with you here in Jerusalem. You’re a founder, a leader of so many different institutions, organizations, and learning programs across Israel, really across the world for the English speaking community and the Hebrew speaking community. Thank you for coming in today.

RABBANIT SHANI TARAGIN. It is an honor and pleasure to be here, Rabbi Benji.

LEVY. So what is Jewish mysticism?

TARAGIN. I’m so happy that I’m here as really an interviewee of Jewish mysticism. Generally people ask questions about Tanach and Jewish thought, but the truth is that if one understands even the depth of Torah, one can appreciate Jewish mysticism.

As we know, Chazal [our Sages] speak about the different methodologies of learning Torah: peshat [contextual and textual reading] and remez [allegorical or allusive meaning] and derash [deeper interpretation] and sod [secret/mystical meaning]. So sod is Jewish mysticism. Sod is that inner, literally the secret, the mystery of the Torah that is not necessarily always apparent to the eye, but throughout Jewish tradition and exegesis we see it was always a part or even a dimension of learning and certainly teaching Torah. I always like to turn to Nachmanides, who is as much as a pashtan [commentator that emphasized the literal meaning of the Torah] as he is someone who understands the pesukim [verses] in context and with such respect and high regard for Midrashei Chazal, for the homiletics of our Sages. He simultaneously will very often incorporate Jewish mysticism al derech hasod [in accordance with Jewish mysticism].

And it’s not just something that we find in the thirteenth century. The Zohar also speaks about how Torah and learning Torah is really meant to be learned on so many different levels. Oraita lagufa, it lei gufa, it lei nishmata. There’s the guf [body], but there’s also the neshama [soul].

LEVY. The body and the soul.

TARAGIN. The body and the soul. And that neshama is really the mystical dimension of learning Torah. And if one then continues through the early mystics in Sefarad [The Iberian Peninsula], the Arizal will unravel different dimensions of the Torah to teach us that there is a world that is beyond, but it’s actually part of our world and there’s a symbiotic relationship between these worlds. So when one learns Torah, one is actually learning the word of Hakadosh Baruch Hu [God]. It’s not only what’s apparent to our eyes, but it’s actually bringing in the divine dimension into this world as well.

LEVY. So with all your teaching, I feel like we’re revealing here that you’re a mystic. Not everyone sees you in that light. What was your path? What was your origin story into this inner wisdom of Jewish tradition through mysticism?

TARAGIN. I’m so happy you asked this. I was just asked this actually by a student, who’s now a teacher, who was just present at a shiur [lesson] that I gave.

LEVY. A lesson.

TARAGIN. It was at a lesson that I gave, and it was on [the Torah portion of] Lech Lecha. And I’ll share some of those torot [teachings] a little later, but in addition to the classical parshanut, the classical commentators, Rashi and Nachmanides, Ibn Ezra, and even classical Jewish thought, I always like to incorporate halacha, Jewish law. All of a sudden my student said, “You had three pages on different selections from the Zohar and Hasidic masters. What happened to you?” And basically, I’m going to share exactly what I told her, and that is that it’s clear that when one starts learning Torah, you have to learn Torat Hanigleh [the revealed aspects of Torah], you have to see what’s revealed before you. You have to learn the text. You have to learn the law. As the Rambam, Maimonides, says, that is really the basar and the lechem. The meat and the bread. I was going to say potatoes, but the meat and the bread of what Torah is [enables] us to basically understand the ratzon, the desire of Hakadosh Baruch Hu [God], for us to even expose ourselves to how to live our lives as people in this world understanding basic religious existentialism.

And the more you learn and the more you appreciate those messages, you also understand that there are other dimensions. As much as I want my students exposed to the world of peshat, of the contextual and textual reading, I want them to also bring it to life through the homiletical teachings that are, in fact, if one really understands the world of Midrash, the world of homiletics, it really is an induction of the text. It’s always based on [what is] sometimes called omko shel pshuto shel mikra, the depth of the peshat [contextual and textual reading]. Then you realize that if you go a little deeper there are even greater messages sometimes. They are messages that are relevant to one’s life.

So that was my first exposure, I would say, after not just exercising, so to speak, the methodologies of peshat and derash but teaching them in depth, then one always wants to go a little further. Hafach ba vhafach ba dekula ba, everything is there.

I think the real trigger was over, I would say, the past five, seven years or so when in addition to having been brought up in chutz laaretz, outside of Israel, and with the teachings of Rabbi Soloveitchik as the foremost philosopher of the twentieth and even going into the twenty-first century. Then you come to Israel and here, as you know very well, when you say the Rav, the connotation and the reference is not to Rabbi Soloveitchik but to Rabbi Kook, Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaKohen Kook. Teachings that outside of Israel, one generally is not as exposed to them. But the more that one lives here and the more that one learns here and the more that one, I’m going to say, even ventures into the writings of Rabbi Kook, one realizes that he’s really adapting this mystical dimension.

And everyone knew that in addition to being a tremendous Torah scholar and talmudist, he was also a mystic. And this is evident in all of his writings, especially on Shir HaShirim, the Song of Songs, especially in his writings of Orot. And I think the past five, seven years or so, and obviously the past two years in particular, have enlivened Rabbi Kook’s writings and shown us that we’re living during a time, as he speaks about, of the mystical dimensions of the Torah, that it’s time to bridge the upper worlds with this world.

And the language of geula, the language of redemption, he says, is really that Pnimiyut HaTorah, is really that inner dimension of Torah. And living through the unfolding of redemption in our time, I think we were all ready for that new language, which really isn’t a new language but a language that has to be incorporated into Torah study and Torah living.

LEVY. So in an ideal world, especially today in the context you’re describing, would all Jews be mystics?

TARAGIN. The answer would be not necessarily that we would be mystics, just as I don’t know if I would say that I’m a a full-fledged mystic in the sense of looking at everything in the world through mystical eyes, but I think that everyone should be engaged in some level of mystical study in order to enliven and enhance their religious and spiritual existence.

LEVY. So this all emanates from the source of the kabbalists. What do you think of when you think of God?

TARAGIN. I think of the infinite. I think of of both dimensions, as we know, starting from the beginning of the Torah, of Elokim, of the universal God, of the God of nature, and I think of the yud, kei, vav, kei [letters that spell the name of God], the personal God, the God who not only commands us but relates to man and ultimately to the Jewish People through a very personal, subjective dimension.

And yes, as you’re saying it, I’m thinking of yud, kei, vav, kei, hayah, hoveh, ve’yihyeh [He was, He is, He will be], and twenty-six and the kabbalistic dimensions. But really when I think of God, I don’t think of God as solely a God of the cosmos. I think of God as a God very much manifest in our world.

LEVY. So in this manifestation, what would you say is the purpose of the Jewish People?

TARAGIN. I also teach Kohelet, so I have to give the answer that I teach on a regular basis.

LEVY. Ecclesiastes.

TARAGIN. Ecclesiastes. “Sof davar hakol nishma, et ha’Elokim yera ve’et mitzvotav shmor ki zeh kol haadam. [The sum of the matter, when all is said and done: Revere God and observe the commandments. For this applies to all humankind.]” And it’s interesting that Ecclesiastes ends with literally the end of davar [the matter], which isn’t just in the context, it doesn’t just mean the end of this thing, the end of this work. He had just spoken about “sof davar hakol nishma,” that every word ultimately is going to be listened to, every word is heard in some way. So that’s what he means. “Sof davar hakol nishma,” every aspect of our being is going to have consequences, has ramifications. Definitely in the world of mystical understanding there are ramifications that we can’t see, there are ramifications that don’t just affect these – the world of the reality in which we live but the upper dimensions of the celestial spheres as well. But that’s really what the purpose of mankind is. “Et ha’Elokim yera,” to fear this God, to live with a constant cognizance of God. “Ve’et mitzvotav shmor,” and to observe His mitzvot. And it’s not just for the self-edification of man, it’s for the purpose of the world, for man’s contribution to the world. Our mitzvot actually affect this world. “Ki zeh kol haadam.” That’s the point of man’s existence.

LEVY. And how does prayer work?

TARAGIN. Oh wow. Wow. Okay, according to whom?

LEVY. What resonates with you?

TARAGIN. Exactly. So teaching Gemara Berachot, I love the sugya, the topic, on daf kaf vav, on page twenty-six of the Talmud, where we find the age-old dispute between Rabbi Yose bar Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi. Do even the beginnings of tefilla [prayer], not just historically but in terms of its ultimate significance, is it keneged avot? Is it parallel to the prayers of our forefathers, which were all spontaneous expressions of emotion? Or is it keneged hakorbanot? Is it parallel to the various sacrifices that one would bring? And we know that this dispute is going to also not just continue as an amoraitic dispute but also through the times of the Rishonim [rabbis of the eleventh to fifteenth century]. So you have the Rambam, Maimonides, who believes, like Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, that tefilla is avoda [serving God]. That tefilla is a recognition that we stand in front of God, whether we’re in the mood or not. We bring the sacrifices.

So on some level, and I think perhaps even [because of] my upbringing, as I said, very much influenced by Rabbi Soloveitchik and those formative years of learning, I think I really do walk around more with that consciousness of tefilla, of those moments where one is extremely mindful of being in the presence of God and to recognize that as I feel vulnerable before God. And at the same time I have that merit of standing before God and literally recalibrating myself, my actions, my presence before God. And even though I stand at seven o’clock in the morning and again at four o’clock in the afternoon and again at nine o’clock at night, that recalibration sets the tone for how I live my life in those interim hours as well.

But certainly, I appreciate Nachmanides’ idea of tefilla ultimately being be’eit tzara, that it’s just that spontaneous outburst of emotion to God. And I think we’ve all felt that numerous times, not only as the understanding of no atheist in a foxhole but appreciating the words, each of the words of tefilla. And here I’m focusing specifically on the Shmoneh Esrei, the Amida, the eighteen, nineteen berachot [blessings] where we express really the ideas of Tanach [Bible], the ideas of the interpretation of my relationship with God on every realm of existence with regard to to health and society and justice and righteousness and wisdom. And it’s difficult to separate oneself from that as well. So ideally, as we know, we’re really supposed to merge them and somehow synthesize both approaches.

For me, that really is tefilla, and I know that you’re waiting for me to say the kabbalistic idea of devekut. I don’t think it’s separate from this –

LEVY. Attachment to God.

TARAGIN. Of attachment to God, that through tefilla we literally bridge our worlds.

I think that it’s not even just a mystical dimension. When you’re standing before God, both with that consciousness of my relationship with God and certainly as I’m expressing myself to God, as I’m reflecting with God, as it’s also a catharsis with God, of course there is going to be an attachment with God. And I know that this has numerous ramifications. Do our tefillot [prayers] affect God? [Do] we change God’s mind? I think if we understand what this devekut [is], what these two sides of attaching ourselves and somehow gaining a greater sense of closeness with God [are], I think we can understand it. We don’t change God’s mind. Again, the infinite God, literally the incorporeal God. We don’t change God’s mind but we do change our relationship with God, and that changes all the dynamics as a result.

LEVY. I think what’s interesting is, I was just thinking when you were speaking that we know that the Talmud refers to prayer as service of the heart, avoda shebalev. And Rabbi Soloveitchik really leaned into this, talking about the service of the heart. But maybe the service of the heart I always understood is the service of the heart, i.e. that emotional space, but maybe it’s also the heart of the service. So you’ve got the heart element, that emotion that you described, like the Ramban, like Nachmanides. But you also have the service element of Maimonides bringing these Talmudic ideas together.

This is described in the Torah. What is the goal of Torah study? Your life has been about teaching. But what is the ultimate goal of Torah study?

TARAGIN. Wow, so our Sages have already told us that there are many goals and that’s first and foremost to learn, to know how to live. Lilmod al manat laasot [to learn in order to act]. But also, we don’t want to make sure that just ourselves, that we’re living an ideal existence. We know that we’re part of Knesset Yisrael, a broader existential soul really of the Jewish People, so we want to affect everyone around us. So the goal is to share the word of God with others as well, lilmod al menat lilamed, to [learn in order to] teach others. And then there is that not just instrumental good but there is that intrinsic good of the Torah that I very much relate to as well, lilmod al menat lilmod [to learn in order to learn].

There is such depth to Torah, there is a transformative, transformative process that takes place when one learns the word of God because you’re learning the word of God. You know, Professor Nechama Leibowitz would say it beautifully. It’s like reading a love letter of Hashem [God]. And when you read that love letter, you naturally, I would say, fall in love. You fall in love with God.

I can’t think of a single time that I don’t walk out of, whether it’s myself teaching Torah, learning Torah with someone, [or learning] from someone [and wanting] to sing “Moshe emet veTorato emet. [The Torah of Moshe is true and that the words are true.]” They’re not only so enhancing of one’s life, they literally tug at your heartstrings. They help every person individually recognize who they are, their own relationship with Hashem, both [what is] subjective and certainly our national destiny, our national history, what propels us to, to continue as a people.

LEVY. So one of the things that you’ve championed and really pioneered is women’s Torah study. And it specifically feels like there’s something unique about women, but is there?

TARAGIN. Yes.

LEVY. Meaning that Jewish mysticism, does it view women and men as the same?

TARAGIN. So it’s so interesting. As someone who I’m sure has heard from others and has studied Jewish mysticism himself, we know that there really are these two aspects of both our relationship with Hashem, our relationship with the world, our relationship one with the other. So I think that the male-female relationship and dimensions are the greatest microcosm. As we know from Song of Songs, but really as Rabbi Akiva [said], [he] basically was adamant about saying if you really want to understand mysticism, he who could say something as ironic as Shir Hashirim [Song of Songs], this love song between the male and the female, really is Kodesh Kadashim, he doesn’t just mean it in the conceptual, the Holy of Holies. He means it literally is the place of the theophany of God. It literally is the place of the manifestation, the revelation of God. And one can ask, how does he know that? Right? He’s not a High Priest. He didn’t go into the Kodesh Kadashim [Holy of Holies].

But we know that in tractate Chagiga we hear of how he himself learned from his own sages and teachers. Back to Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, he learned the world of mysticism. He went into this world of Pardes [kabbalistic biblical exegesis], into the world of sod, and came out also, ala beshalom veyarad beshalom [he went up in peace and came back down in peace], teaching us that, of course, he knew this world, so he could speak about this beautiful dimension of the ish [man] and isha [woman], the mekabel and the one who is literally the acceptor and the giver, the mashpia, the different dimensions of aspects of relationships.

And as we know in any relationship, but especially the male and female, not only physiologically but also, this has been studied for the past hundred years, the different psyche of the male and the female, and the more that one can understand that in one’s own relationship the more one can then take that to a relationship with Hashem [or] a relationship with others.

So yes, within the world of Torah I think there are certain aspects. When people ask me all the time, is there a different Torat nashim [Torah for women]? Meaning if we were both learning the same halachic sugya [unit of discussion in the Talmud], I should certainly hope that we would reach the same legal conclusions in halacha. At the same time, the different perspectives, I’ll call it even the meta-halachic ideas, I think we would see [them] a little differently. I think we would apply them to our lives a little differently. I think they would tug at different heartstrings differently. I think that we would relay them with different nuances. And therefore, yes, it’s important for women also, not just to learn the language of mysticism but to be involved in the discussion and interpretation so that everyone can gain much more.

LEVY. Should Judaism be hard or easy?

TARAGIN. Great question because I think about this all the time. Every time we sing, “Geshmak to be a Yid,” that it’s great to be a Jew, I’m thinking, I don’t know, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, they said it was very hard to be Jewish. And to be honest, I think I personally relate more to the struggles in the sense that I want to teach people that it is a struggle. I think if it’s easy to be Jewish then we lose some of – not just the meaning to the end. We lose the investment, we lose the inner dimensions.

Our Sages teach us that there’s value in the struggle. Yagata umatzata taamin. If you exert yourself and then you find something, believe it. Lo yagata umatzata al taamin. If you didn’t engage, you didn’t struggle, and you found something, don’t believe. And what are they trying to teach us? That you’ll gain much more. You’ll really find [more] when you struggle, when you exert yourself.

And the struggle doesn’t have to be the same financial hardships as one hundred years ago, but it does mean that we do have to struggle, we have to ask questions, we have to search for the answers. We have to live life as a Jew [and] that of course demands sacrifice: sacrifice sometimes of personal pleasures, sacrifice of other pursuits, sacrifice of different lifestyles. So yes, I think that it’s good that Judaism is hard.

LEVY. So why did God create the world?

TARAGIN. That’s Kohelet. That’s Ecclesiastes. The truth is that it’s not entirely Ecclesiastes, which is more: What is the purpose of man in this world? And Aryeh Kaplan, a great kabbalist and definitely a student and teacher of Jewish mysticism, said we’re not God. So we’ll never really know why God created the world. Our Sages provide numerous answers, whether it’s to provide for chesed, for kindness, the very fact that God literally shares godliness with the world is remarkable.

And certainly in Jewish mysticism, and I think that this is a very true idea, not just [one] that I personally believe in, but one sees it not only in the traditional sources of Hasidism, of the Tanya, that when God created the world, the point was that the world should be a reflection of God. But God can’t and is not contained within the finite. As soon as I say that even: God cannot, right, that limits God, but God can be in the finite, but not in the same manner, not in the same form as He is in the infinite. So through creating the world, through creating man, He basically has created different expressions of Godliness.

And our challenge is to bring more God into the world by expressing more of our godliness. And the greatest way is through the Torah, through following the mitzvot, through engaging in this love letter of Hashem.

LEVY. So in this journey, can we do something against God’s will?

TARAGIN. We can. We’re capable. Yes, we’re capable of dismissing godliness. We’re capable of undermining the existence of God. We’re capable even of not taking advantage of bringing more godliness, which is certainly the will of God. So we are capable.

God, as part of really the creation of a physical world, has left that space that we call bechira chofshit, free choice. God wants us to actively bring that godliness into the world. God wants us to choose a relationship with God.

Rabbi Saadya Gaon, one of the greatest philosophers, going back even to the tenth century, explained that man should have really been able to figure this out. Man should have understood the will of God. And yet, we were both individually and collectively choosing to undermine the will of God. Until God, through Abraham and his descendants, said: Okay, I’m going to give you that blueprint. I’m going to share with you how you can bring Godliness into the world. That’s the Torah. That’s the word of Hashem. But we still have that bechira chofshit [free will]. We still have that freedom of choice to undermine that will of Hashem.

I think the one component that perhaps suspends that freedom of choice is when we want to return to Hashem, when we want to return to God. And then, ideally, we should want to do this on our own. And yet, God says, if you really want to return, when we ask God: hashiveinu Hashem eilecha [return us to You], sometimes God even suspends that freedom of choice so that we can return to ourselves and ultimately return to God.

LEVY. So in this journey of return, there’s going to be an ultimate return, which is Mashiach [the Messiah].

TARAGIN. Yes.

LEVY. What do you think of when you think of Mashiach?

TARAGIN. I think of Knesset Yisrael, literally the People of Israel coming together, which we already see in our days. And I don’t just mean the unity on the streets, I mean the first expression that we find in the words of the prophets of kibbutz galuyot, of bringing the ingathering of exiles back to Israel. And that really is that geula, is that bringing of the infinite, the bringing of Godliness into the world through stage number one, as we say in our tefilla, through both of the righteous ones ridding [the world] of velamalshinim, all those who are speaking badly of righteousness, all those who are supporting evil, and I don’t think I have to elaborate too much here, and then to see the restoration of justice.

So this is all part of meshihut, all part of this ideal where we [are] still going to make mistakes. You know, after Mashiach comes we still have that freedom of choice. How much is really up to debate amongst various Sages, but then et tzemach David avdecha mehera tatzmiach [may the plant of your servant David grow quickly], then to see the blossoming. And these are words that we find by the prophets.

So my understanding of Mashiach is definitely based on on the words of prophets like Isaiah and Zechariah and certainly Rabbi Kook, who spoke a lot about the unfolding of redemption through Mashiach as – and the Rambam – as a very natural state, as the Jewish people coming together, coming to Israel, which is the last stage of the teshuva, the process of return, even the individual return. Once we come back to Israel and can keep all the mitzvot, all the commandments, including the land-based commandments, then there will be a greater manifestation of God, of Hashem, in this world through the people of Israel, the Land of Israel. And Mashiach is that state of not only peace within the Jewish People, international peace, but also the state where we have a leader who shows us, who can model for us what that perfect synthesis of living a life of Torah within a political, a natural world is all about.

LEVY. So in 1948 there was actually a physical manifestation of what it seems you’re describing from the prophets, which is still unfolding today. Do you see the State of Israel as part of the final redemption?

TARAGIN. Definitely. And I’ll quote Rabbi Kook as etchalta de’geula. It’s the beginning [of redemption]. And all you have to do is really open up the prophets of Tanach to see it, which is why I always feel badly for those who don’t have the front row during these years of seeing the unfolding of this redemption.

So that was the beginning, which really is what we speak about, of sovereignty in the Land of Israel, autonomy being restored. You open up to the fourteenth chapter of Zechariah and you see he speaks exactly about this, followed by literally the redemption of Jerusalem. So we look at 1948, we see just like the time period between the First and the Second Temple, there were nineteen years between the restoration of autonomy and the rebuilding of Jerusalem. We had nineteen years between the restoration of autonomy in modern-day eras and the rebuilding of Jerusalem, which I believe Rabbi Akiva, also a mystic and Talmudist and philosopher, and one of our greatest leaders of all time who enabled the perpetuation of a Torah shebe’al peh, of the Oral Law, he was the one to see this and laugh as he recognized not only that there will be another stage of redemption, another rebuilding. He didn’t necessarily laugh when he spoke about the rebuilding of the Temple. He laughed when he spoke about the rebuilding and the resettlement of Jerusalem. And I think he laughs because he sees that this stage of redemption literally is modeled after the previous one.

So we have our nineteen years and we have the resettlement of Jerusalem. And we know that the next stages are, in fact, kibbutz galuyot, the ingathering of exiles, and then after kabetz nidachenu [ingathering of exiles], then we have the restoration of righteousness, the continued rebuilding of Jerusalem, the final banishment of evil forces and sources. And then we have restoration of malchut [sovereignty]. One can even argue that not only 1948 with the establishment of sovereignty in Israel, but with the establishment of the Knesset, of government, that that was also the beginning. It’s definitely not a theocratic government but a government that takes Jewish law, Mishpat Ivri, into account. [It] certainly is the beginning of what’s to come.

LEVY. We spoke about Israel and the specific place of the Jewish People, but what is the greatest challenge facing the world at large?

TARAGIN. So I think the same challenge that’s facing the Jewish People that I’m sure many spoke about is also facing the world at large. And that is unity. And within the people of Israel, just a greater sense of understanding unity.

Unity doesn’t mean everyone becomes literally one and shares the same exact beliefs. Unity means that we can exist as one people with multiple ideas and thoughts and opinions within the Jewish People, although according to the precepts and principles of the Torah. In the world it means literally unifying as a people who also recognize and respect one another.

There’s so much animosity, everyone downplaying and undermining everyone else. If we would only take a few moments just to listen, to disagree but with respect, to be able to hear so many expressions.

Rabbi Kook said it beautifully when he speaks about truth and tolerance and pluralism. So it’s true, he said, that we have to be tolerant but not within the Jewish People, only tolerant of observance of mitzvot, but pluralistic of so many thoughts. He says if there is a thought in this world, if there is a political theory in this world, then it must be that God wants that theory in this world and any theory has some expression of Godliness except those that undermine God. Those different theories of Godliness, that means that if we can understand them, that doesn’t mean that we should adopt them, but if we can understand them we’ll appreciate a much broader understanding of God.

Obviously, the greatest, the most direct understanding of Godliness is the Torah. But at the same time, we could just listen and process a little more and thereby respect. I think we’d be even closer to that stage of redemption.

LEVY. I’m smiling because the first time I learned that Rabbi Kook was actually with your husband, in Yeshivat Hakotel in the Old City. And I remember him going through a beautiful – I’m sure you’re familiar with it. And then Rabbi Schachter spoke actually, and I gave him a ride home. And I remember first learning that and when you learn something it sticks with you, but it’s this unity without uniformity. It’s a difficult balance to be able to achieve.

TARAGIN. Correct. Very difficult.

LEVY. So how is modernity – we’ve talked about it in the sense of the State of Israel, but how has it transformed Jewish mysticism?

TARAGIN. So in this modern world, even though today everyone will say we’re now postmodern, but the postmodern world, which is one that’s depicted as one of multiple truths, of one where it’s very difficult to qualify a truth. On one hand, one can argue that that’s very dangerous. Everything becomes very subjective. I can qualify myself as whatever I want, whatever gender, whatever age, and as we know, that really can lead to greater confusion and undermining of some sense of truth.

But then there is the soft postmodernism, which is really, again, Rabbi Kook’s vision, and those that are taught by Rabbi Shagar, Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg, for example. I think that if we teach these ideas of not just multiple truths but different perspectives in in this modern world, I would even argue let’s go back to modern, away from postmodern, just to requalify and be able to define ideas and truths, recognizing again that there are multiple truths. That is in fact, I think, a window to mysticism that sees every aspect of this world through different dimensions.

LEVY. Amazing, so it’s given us a different platform or perspective to be able to view this.

TARAGIN. Exactly.

LEVY. What is the difference between Jewish mysticism and other forms of mysticism or mystical traditions?

TARAGIN. There are numerous doctoral theses about this. But Jewish mysticism is appreciating again that Pnimiyut HaTorah is not just looking around at the world, which many, many ancient mystics did. And by the way, Jewish mysticism incorporates certain aspects of universal mysticism, whether it’s through constellations of the stars, the study of astronomy, and we know that most Jewish mystics try to appreciate the inner dimensions of the world, just as Maimonides tells us, both through the world, getting to know the world. Scientists can ultimately be mystics and there’s more and more literature about this from the days of the Templars through modern day times. But Jewish mysticism means we’re also going to use the template that God gave us. We’re going to use the Torah. We’re going to get to know God and the inner dimensions of God, not just through nature but through every single word that God has shared with us.

LEVY. So do you have to be religious to study it?

TARAGIN. You have to have respect for Torah, and you have to believe that Torah is the word of God that was revealed to us at Mount Sinai.

LEVY. And can it be dangerous?

TARAGIN. To engage in Jewish mysticism without understanding certain core beliefs of Judaism, yes. It’s almost as if one is going to taste the ingredients of a cake without putting it together and appreciating the cake.

LEVY. Here’s a bit of a raw egg.

TARAGIN. Exactly. Thank you. Here’s a raw egg. Here’s vanilla extract, and you don’t even understand what function it has. So first you have to literally eat the cake. You have to digest the cake. You have to appreciate the cake. You have to learn the peshat [contextual and textual reading]. You have to learn, really, the words of Torah. You have to learn halacha. If you really want to understand the inner dimension, you have to appreciate how the basic dimension expresses itself in this world. And then you can go back and then you can realize, wow, this cake was really palatable. What was in this cake? Now you can begin to dissect the egg and the extract, and then you’ll appreciate it more knowing ultimately what the composition is all about.

LEVY. So this composition expresses itself in many different facets of life. And you individually wear many hats [of] many different institutions, organizations. You’re a wife, you’re a mother, you are a teacher. There are so many different areas. How has Jewish mysticism practically, and if you can give one example, that would be amazing, affected your life in terms of relationships, in terms of how you interact with certain individuals or in specific relationships?

TARAGIN. Wow. Wow. So firstly, definitely the idea of knowing that in mysticism, in Jewish mysticism, there is that expression of my relationship with God through the male and the female. And certainly, many know that one of my favorite books of Tanach, of the Bible, is the Song of Songs. And particularly as a woman, it’s told more from the woman’s voice, the raaya, the female persona. So definitely in my own marriage, appreciating that, even starting with that, appreciating that the Song of Songs really is about that physical relationship that then we know has so many mystical ramifications of whether it’s that tension between the body and the soul, the tension between myself and the sefirot, the different dimensions of the world, and definitely the more classic approach of Maimonides, the relationship between myself and God, and then the classic approach of Rashi, the relationship between the people of Israel and the God of Israel.

So, definitely through, I would say, the sources of mysticism of the – learning the words of the Torah in the book of Ezekiel, the Maaseh Merkava, the theophany of God, understanding how that expresses itself in our physical world through initially a Mishkan, a Sanctuary, and then the Mikdash, the Temple, and ultimately how we can build that in our own lives. And then through the Song of Songs as well, the way that it just manifests itself in my thinking about relationships between people and who’s running away from whom.

And by the way, in Jewish mysticism, the I, which is generally the female persona, in peshat [contextual and textual reading], many understand it as us or as we’re the capricious ones. You know, God is the constant. So we’re Knesset Yisrael [collective soul of the Jewish People]. Right, Knesset Yisrael is the feminine. In mystical terminology, the feminine is actually a dimension of God, is the Shechina. So God is the capricious one, hiding and revealing.

And we’re the ones who say, we’re here God, and we just want that relationship with You.

I don’t think a day goes by without me thinking about that. I don’t think a day goes by without literally praying for that. I think every tefilla, that’s really what I ask God for. God, please allow me, show me, show me those inner dimensions so that I can be, as you said, the best wife and daughter and mother and sister and teacher and ultimately the best eved Hashem [servant of God] that I can be.

LEVY. Incredible. So it’s amazing to see it in your life and as that expression of these teachings and the teachings as an expression of life. Just for teaching for teaching’s sake, you mentioned a term before about learning for the sake of learning. Is there a teaching that you carry with you or that resonates currently that you’d like to share to conclude this amazing conversation?

TARAGIN. So maybe because we just read it just two weeks ago, maybe because I really do think about this all the time, maybe because I believe especially today that the Jewish People belong in the Land of Israel and that’s where not only individual godliness is most expressed but our national godliness, that I really do believe that God is waiting for all of us to be here. And each one contributes in their own individual way to bringing that geula [redemption], to bringing that redemption, because once we’re here, that relationship with God is intensified.

So I think of Hashem’s call to Abraham, which really is that call to each and every one of us, of lech lecha [go forth]. “Lech lecha me’artzecha, mimoladetecha, mibeit avicha,” go forth from your land, from your birthplace, from your family, from your father’s home, “el haaretz asher areka,” to that land that I shall show you.

And the Zohar beautifully says, “Lech lecha legarmecha.” And go to you, “le’atzmecha.” Go and return to who you really are. That God commands us every day, not just through that historic lech lecha of Abraham sacrificing his past, and not only through the repetitive lech lecha of his willingness and really the imploration of God for him to sacrifice his future through the sacrifice of Isaac, but that constant lech lecha that we’re all supposed to be hearing, and that’s exactly what the Zohar is teaching us.

That God speaks to us and says, go and find yourself. That if you really want to find the land that’s good for you, if you really want to find what that future for you entails, then return to who you are. And God is basically saying, I created you as tzelem Elokim, in My image. So go and recognize that godliness within you, recognize that potential, recognize that relationship that you have with me.

And once you do that, then not only are you not really sacrificing your past, it means finding who you are in the present. And that obviously propels definitely and where we’re supposed to go, our trajectory for the future.

LEVY. So, Rabbanit Shani Taragin, it’s clear what your purpose is here, what you’ve found in yourself. And we just pray that God continues to bless you with the capacity to lean into that deeper and deeper, to find that inner dimension, and through that process, help others discover their direction and just amplify that, deepen that through everything you do. Thank you so much.

TARAGIN. Thank you. And if I can just add at the end that that’s really something to complete the first question of this journey that I’ve taken. So in teaching, I find that it’s exactly that language that you just expressed. That in addition to teaching all different methodologies of Torah, I found that today we need to develop this language. We need to develop a language of geula [redemption]. And this language of geula, this language really of Pnimiyut HaTorah [inner dimensions of Torah], is not only bringing people closer to Judaism, not only getting them to actually tasting the cake really and appreciating the depth of Judaism, but ultimately it is bringing us closer to the stages of what we as a people are meant to be.

LEVY. May we arrive there soon. Thank you.

TARAGIN. Amen.

LEVY. Thank you.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Dr. Ora Wiskind: How do you Read a Mystical Text?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Dr. Ora Wiskind, professor and author, to discuss her life journey, both as a Jew and as an academic, and her attitude towards mysticism.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Debbie Stone: Can Prayer Be Taught?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Dr. Debbie Stone, an educator of young people, about how she teaches prayer.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

5 Lessons from the Parsha Where Moshe Disappears

Parshat Tetzaveh forces a question that modern culture struggles to answer: Can true influence require a willingness to be forgotten?

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

Rav Tzadok of Lublin on History and Halacha

Rav Tzadok held fascinating views on the history of rabbinic Judaism, but his writings are often cryptic and challenging to understand. Here’s…

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.