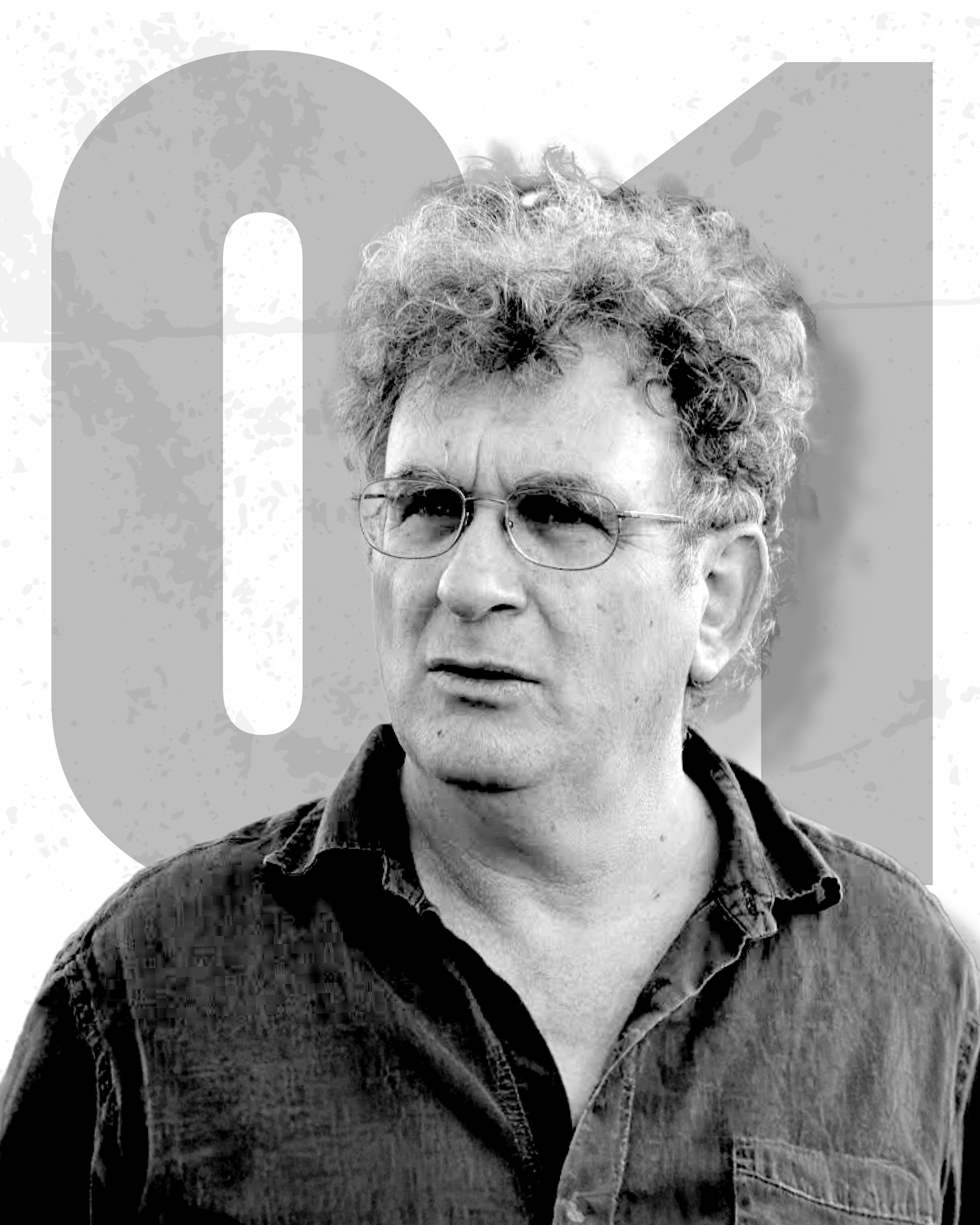

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

A lifelong seeker of truth, Dr. Chava Green has always been drawn to exploring the complexities of the world. As a college student she explored different areas of thought, eventually learning more about Judaism and strengthening her Jewish identity. In turn, Chava’s journey guided her to the rich tradition of Jewish mysticism.

Chava Green is the founder of The Hasidic Feminist Platform. She completed her PhD in religion at Emory University, writing her dissertation on Hasidic feminism. Chava is currently working on a book entitled The Geulah is Female.

Now, she joins us to answer eighteen questions on Jewish mysticism with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy including the role of women in the Messianic Era and how we can see God in the everyday.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Chava Green, such a privilege and pleasure to be sitting with you. Thank you so much for joining us. “The Hasidic Face of Feminism,” that was the dissertation of your PhD and it sums up a unique perspective that you bring as a mystic. Thank you so much.

DR CHAVA GREEN. Thank you for having me.

LEVY. So what is Jewish mysticism?

GREEN. That’s a great question to start off with. So, let’s separate the two for a moment. What is mysticism in general? So I would say there’s two main components.

One is that everything in the world has a soul and a body. And so the mystical element of every religion is the soul of it. We all understand the rituals, the practices, the community of any religion. And the mysticism is that inner core experience, the soul of it.1

The other part is that it’s esoteric. Usually it’s, you know, limited to a select few and every generation would pass down. And in Judaism we have a unique way of understanding Jewish mysticism. We call it Kabbala. What does Kabbala mean? It means to receive. And so Jewish mysticism is much more about combining a received tradition, that secret tradition, with your own personal experience of God, a direct experience of God. Whereas a lot of the rituals in the body of Judaism are mediated, like our relationship with God is mediated through that. Jewish mysticism gives us moments where we have, we pierce through that –

LEVY. It’s more direct.

GREEN. And we, and we just have a direct connection to God.

LEVY. Beautiful. So how did you get into this stuff?

GREEN. That’s a great question. I will spare you my entire life story because it is a long story.

LEVY. I know it’s a fascinating one.

GREEN. But I would say in college, I was – my English name is Vera. And as I started learning about Judaism, I realized our names have this prophetic quality.

And Vera means truth, like verdad, veritas. And so I was always seeking the truth. And what that caused me to do was every time I encountered something, [I would] go deeper and deeper, like down this rabbit hole. But why? But what is the reason? And I looked in a lot of different places: social justice, liberal philosophy, feminism.

And when I encountered Judaism I felt like I had found my personal home, my spiritual home, my identity as a Jew started blossoming. And as I was learning more about Judaism, I was always seeking that really core truth. And that led me to Jewish mysticism.

LEVY. Wow. So in an ideal world, would all Jews be mystics?

GREEN. Absolutely. Absolutely, because our relationship with Torah study, with God. You know, in Kabbala it speaks about two different ways of approaching the divine: hearing and seeing. And [throughout] most of Jewish history, we’ve had this heard experience2 of Judaism where we receive it from somebody, our teacher, and it has a certain limitation. And the idea is when Mashiach, the redeemer, comes, we will see Godliness. And Jewish mysticism gives us that opportunity to have that little insight into seeing God.

LEVY. So what do you think of when you think of God? You spoke about seeing God, but what is this thing you’re seeing?

GREEN. So I think God for me has both a personal resonance and a more philosophical one. And the personal experience of God is that the world itself, like I spoke about the body and the soul, God is the soul of the world, but the world is His body. He’s beyond this place and yet He is also in this place. And so when we experience our life in the world, we have to understand it’s the body of God.3 And so we can constantly be experiencing and being in the presence of God through a shift in our consciousness. And so for me, coming from the Chabad tradition, there and from the Baal Shem Tov in the Hasidic movement, there was a real transformation in the understanding of God when we think about something in Hebrew called hashgacha pratit, divine direct providence. And I think of it more as understanding really deeply [that] God is literally watching over your shoulder, in a loving way, not a creepy way.

But, you know, like, I’ll just give an example this past weekend. I was – I really wanted to get new high chairs. I have three kids. They’re all fighting over this one cool wooden high chair that we have. And I was like, I really want the Stokke high chair. It’s like 250 dollars. I have three kids. I was like, I cannot drop 1,000 dollars on a high chair. And I mentioned it to my dad, and he’s like, that’s expensive. And I mentioned it to my mom. And she was like, okay. The next day, she was at a thrift store and she found that chair for me for five dollars. And I didn’t think that’s random or I’m so lucky. I said, thank you Hashem. Wow. Something I wanted so deeply, Hashem knows, Hashem [is] with me. God is with me in that in my experience of life. And when I have experiences like that, and I directly understand it’s part of my relationship with God, then my whole life is built upon that premise.

LEVY. Well I don’t know if the kids drop stuff on the floor, but my sister owns a company called Catchy, which catches it. So if it’s meant to be now, I’m happy to organize for you for free, [for] all three of them.

GREEN. That would be wonderful. Thank you.

LEVY. So what’s the purpose of the Jewish People?

GREEN. Oof, good question. So the classic answer is that we’re lamplighters. But what does that mean? So God came into the world, and it says actually there’s like a three-part reality: God, Torah, and the Jewish People. And the question is, which came first? Torah or the Jewish People? And actually, one interesting answer that I saw, which was so simple yet so brilliant, was the Torah refers already to the Jewish People. So the Jewish People must have come before the Torah.4

Because when the Torah already comes into the world and even comes into God’s existence, the Jewish People are there before. And so what that means is that we are the representatives of Godliness in the world. And you can unfold that in many different ways: morality, community, the legal system, all these things that are sourced in the Torah and in Judaism, but that is on an abstract level.

Practically, the role of the Jewish People is [for] each of us in our individual lives to reveal Godliness in the world. So I was just coming out from the subway and there was a woman struggling with her bag. And I thought I could just walk by her and [then] I thought, no, I can make a Kiddush Hashem, sanctifying God’s name. And I turned and I said, can I help you with that? It would be my pleasure. And I carried the bag up for her. Like these little moments where we think we’re here to show the world that it’s a loving, caring place.

LEVY. Beautiful. And then how does prayer work?

GREEN. So I thought you’d probably ask me about prayer. And I was thinking it’s funny, not, I don’t have much prayer going on in my life right now. I’m like, my three little kids, it’s, I’m lucky if I open a prayer book. But, beyond that, on a deeper, more mystical level, prayer just simply is building that bridge between us and God.

Because many philosophers and theologians over [the course of] history have understood the relationship between humans and God in so many ways. And famously, Thomas Jefferson was a deist. He was like: God made the world and then he backed off. But we fundamentally don’t believe that in Judaism.

We believe that God wants to have a relationship with us. And so you could think, what’s the point of prayer if everything God does is good? Isn’t reality the best reality? Why should I try to change it? You know? But the idea is that God wants that relationship. So just like for me and my children, in a lot of the ways we understand the more mystical elements of Judaism, because they become very abstract, is [that] really they’re reflected in our own relationships with the people around us. So I said with my own children, I can say this is the best thing for you, but then I see that they’re asking me for something else.

And I realize like, right, because I’m that provider for them. And when they open up to me about what they want, that builds the relationship. I’m not just determining what their world is. And so too with God. God gave each one of us our inner world, our desires, our unique situations. And that creates a space for us to reach out to Him for that transformation.

LEVY. Prayer is that vehicle.

GREEN. Prayer is that vehicle.

LEVY. And what about Torah study? What is the goal of Torah study?

GREEN. Hmm. What’s the goal of Torah study? First, I’ll say there’s an aspect of Torah study that’s lishma, just, which means for the sake of itself. To study something because it was given to us from God. It’s the blueprint of creation.5 And to study it in a way that it’s beyond any sort of reward, it’s beyond any sort of reason.

We just study for the sake of itself. But what does it do? It gives us insight into God’s world. And the Torah, because the Torah, the Jewish People, and God are all one, it also opens up our own selves. It gives us insight into who we are. And all the pieces fit together because if we’re going to be this model for the world as lamplighters, we have to understand what is the light we’re shining. And Torah is that light.

LEVY. So does the Torah view men and women as different from a mystical perspective?

GREEN. Oh, okay. I’ll try to keep this answer short. This could be hard.

LEVY. Based on your PhD.

GREEN. Right. So because I’m an academic and I wrote a whole dissertation on this, I will in the beginning just comment on the language.

Men and women. So when we think about gender in Judaism, there are many registers. So men and women are the – you could say the most apparent biological registers of gender. Then you have masculinity and femininity, which in Judaism is mashpia – mekabel, giver – receiver, a dynamic there. And then you have, going up back into God’s essence, this constant dance between HaKadosh Baruch Hu, the Holy Blessed One and the Shechina, the feminine. And so to ask if Jewish mysticism views men and women as different, it’s almost a non-question because the fact that God built into the world men and women, like automatically, reveals the dynamic that has to occur between them. And in order to have that dynamic be productive there has to be friction. And so, of course there’s a difference.

On the other hand, in each register of what I mentioned before, like the physical, the spiritual, the spirit, the emotional, there’s so much nuance and overlap. And so we can often step into our more feminine or masculine sides, and so that difference is very concrete on the biological level and yet very nuanced as we go more and more abstract.

LEVY. So there is a difference.

GREEN. There is a difference, yes.

LEVY. And that’s what makes life beautiful.

GREEN. Yes.

LEVY. What is the biggest obstacle to living a more spiritual life?

GREEN. Hmm, social media.

LEVY. Do you feel that?

GREEN. I really feel that way. Not because of the time wasted. I think that’s one piece. But I’m more concerned with the way it’s changing our consciousness, our way of being in the world, our ability to think slowly and deeply and to carve out time that is in ourselves.

On the other hand, I will say that there’s one aspect of Jewish mysticism and spirituality that demands [one’s] presence and demands [one’s] lengthy ability to concentrate and to contemplate. On the other hand, there’s also an aspect of Jewish mysticism that I was speaking about before, which is seeing God in the everyday. And in that sense, I think the issue with social media is that, you know, this body and soul idea, its oftentimes any person, any personality, persona, influencer on social media, it’s very hard to reach into the soul of who they are. It’s very, very difficult because most people online have a persona online that is somewhat related to who they are in real life. But even me, like I’m not the same right now as I was yesterday in my house. And so we start losing some of that soul of really the broader world. Not just other people, but reading the news creates this sense in us that we, I, know what’s going on. But we just know the body of what’s going on. We don’t know the soul of it. And to live a spiritual life and always be searching for that inner sweet core, you know, it’s like eating an orange and you’re just constantly eating the peel and you never get to the fruit. And what kind of life is that?

LEVY. It’s more bitter.

GREEN. It’s definitely bitter. It’s not sustaining.

LEVY. But God created the world as a body for that soul. So the soul was always there. So why did God create the world?

GREEN. Hmm. Well, why did God create the world? God created the world because in the language of Jewish mysticism, He wanted to have a home in the lowest place in existence.6 I’m sure all the Chabad people on here are going to say this because this is –

LEVY. Dira betachtonim [a dwelling in the lowly realms].

GREEN. Dira betachtonim – because this is the fundamental premise of the Hasidic movement of the Baal Shem Tov. And taken through the generations is that [question of ] why did God create the world? Because it’s very nice for God to be God alone. And we can’t even conceptualize what that looks like. But imagine just the pure existence and joy and goodness of God without any tension, without any battle with the Jewish People [or] with the world. That seems ideal. And yet we go through this epic, huge journey of creation and thousands of years of the Jewish People [and] the world unfolding. And the world as it is now looks nothing like it did a thousand years ago or before. How does this benefit God? What would be the point of this? And this drove me crazy when I was secular – trying to figure it out. My dad would always say just to be happy is the purpose of life.

And it’s ironic because why did God create the world? Why did he want a dwelling place in the lowest world? It says in the language of Kabbala that He had a taava, a desire. It’s not a rational, logical – you’re not making a philosophical argument. We’re saying there’s a place within God beyond reason and understanding and it just is a desire. And we know this within ourselves. Sometimes we really want something and maybe your spouse is like, what? We don’t have money. We don’t need that. And you’re like, I really want it. And I can’t change that, you know. So there’s a piece in God that really wanted a world. He really wanted to be at home in the world. And in a way, it makes sense because [no matter what] we conceptualize as the most spiritual abstract reality, the world, the physicality of the world is the exact opposite of that. And God wanted to show, I don’t know, us, Himself, wanted to experience what it would be like to be so unlimited; He could be in the place that seems exactly opposite to him. He could be found in the most base materiality of the world itself.

LEVY. And if it’s hard to try and understand your spouse’s desire, how much more so God’s? But that’s the path of what we’re here to do.

GREEN. Yeah.

LEVY. And we do that through free will, or do we? Does free will actually exist?

GREEN. Does free will exist? So based off of my understanding of this, I believe that we really only have free will in a philosophical sense in matters of morality, of choosing good and bad. Because if we have to step back and see our relationship with God, do we have repercussions for our actions? And so there has to be a point where we’re held accountable, responsible for our choices.

But really those moments are very few and far between. Those real moments where you’re making a choice that is unencumbered by other conditions and is just free. Because what is a free choice? It means it’s not already determined in some sense. In practicality, most of our choices are determined. To go back to Divine Providence, God arranges our life, you know. So I think about the biggest choices in my life. I remember when I was dating, I was debating whether or not I wanted to go on shlichut, to be an outreach professional, like Chabad –

LEVY. Go as an emissary.

GREEN. Emissary – and spread the teachings of Judaism, or if I wanted to go into academia. And I was torn between these two life paths. And I went to the resting place of the Lubavitcher Rabbi [Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson]. And I sat there praying to God [to] give me clarity. And I had this inner vision of Rabbi Schneerson and his father-in-law, the Frierdiker Rabbi, looking at me saying: “You have to choose. If you want to get married, if you want to find your soulmate, you have to choose which path.” And I walked away from that understanding that I did have a choice. I had a radical moment of: Do I go down this path and apply to graduate school or do I go down this path and go on outreach? And so it felt like a choice to me. But looking back, there is no way I could have done the other one. Because from God’s perspective, everything is. He’s above time. He knows what you’re going to choose. He knows how your life is arranged. But He gives us, in our understanding, the ability to feel that we’re making those choices.

LEVY. Well, I believe that you chose academia and through that you chose shlichut; you chose doing a mission. And that’s what has been your platform, no? That’s where you’ve shared that divine light in a unique way. You could have gone to some country in the world, but you’re doing it through this other vehicle. And that’s really to bring us, you know, the whole point of shlichut, this sense of being an emissary of the Lubavitcher Rabbi, is really to bring Mashiach [the Messiah], to bring this incredible time. What is Mashiach?

GREEN. Hmm. What is Mashiach? So, in the language of mysticism, Mashiach is when the surrounding energy that cannot enter the world, because it will destroy it with its brilliance, will be able to be contained within the indwelling presence of God. Sovev kol almin in memalei kol almin:7 the surrounding light in the light that fills the world. And because in our reality now it’s one or the other: You either have this crazy intense light, and that’s people who have such passion and they just seem like they can’t fit into reality. They can’t carry that intense power and bring it down into everyday life. And then you have people that seem like they’re in the day-to-day life of the world and yet they don’t have a strong connection to infinity. And so when Mashiach comes, we’re going to be able to experience both of those together.

We’re going to be in our everyday lives, in our kids and our jobs and whatever we’re doing, and it’s going to be infused with the unlimited energy and reality of God in a way that I [mentioned] before [about] just seeing Godliness in the world. And so the other aspect of that, to go back to a little bit of the masculine feminine thing, is that we have two paradigms in Judaism: of truth, emet, and emuna, faith. And most of the galut, of exile, has been characterized by this juxtaposition between the two – [when] we know what’s true and times where we’re in such darkness, like the sun and the moon. And we’re in this moon of darkness and it’s like, what is truth? When Mashiach comes, we’re going to have both of them together. We’re going to have that.8

LEVY. It’s like an eclipse.

GREEN. Yeah, we’re going to have the sun – the light of the moon, it says in Kabbala, will be as strong as the light of the sun. They will both shine brilliantly. So everything in our present time that we don’t value [and] don’t see the benefit of, like the materiality of the world, it will shine forth Godliness in the same way that Torah and mitzvot [the commandments] shine Godliness now.

LEVY. What does that mean? Because from a mystical perspective, the moon has receiver energy, right? And the sun is the provider, the mashpia.

GREEN. Yeah, the giver.

LEVY. The giver. So if the receiver is also going to be giving, is there any reception?

GREEN. Hmm. It’s a great question. It’s something I’m actually working on a new book about called The Geulah is Female. And I’m trying to do a really, really deep dive into what will be the relationship between masculine and feminine in the time of redemption, with the premise that [it] is the ideal state of gender relations.

LEVY. Well, if it’s the Messianic time, then it must be, no?

GREEN. Yes, right. And because of the exilic reality, in many ways, the moon was diminished. There’s a famous midrash [expansive biblical exegesis] that says: Why does it say God made the sun and the moon as two great lights? And yet one is great and one is small because the moon was diminished. And so the feminine was diminished over this time period of human history. And we’re so close to the Messianic Era. There are many signs of it, but one of them is the great elevation of women’s voices. I mean, the fact that I’m sitting here today and it’s totally normal, and I’m sure you guys thought we need to have some women speak, you know.

LEVY. No, no. We wanted to have you because you’re great.

GREEN. Okay, well, thank you. But just the pure fact of being here two, three hundred years ago wouldn’t have been possible. Women didn’t even have access to Torah study on the level that I have access to, that women have. And so we’ve seen this great elevation of the feminine. And so in the Messianic time, we will see what the feminine, what the receiver gives, in a way that will be as clear as what the giver gives.

LEVY. Amazing.

GREEN. Because now, only what the giver gives is obvious. What the receiver gives is hidden.

LEVY. So there’s almost a hint to reality unfolding in this direction by virtue of the fact that you’re sitting here and have that presence.

GREEN. Yeah.

LEVY. And what about things like the State of Israel? Is that part of the final redemption?

GREEN. Hmm. Well, I’m not so much into politics.

LEVY. From a not a political but mystical perspective.

GREEN. From a mystical perspective, there’s not necessarily a state. There’s not necessarily this idea of political nationhood that I’ve seen, so much, in the mystical sources. There’s much more an idea about the land of Israel, Eretz Yisrael, being a place where the eyes of God are on it all the time. But interestingly, and this kind of ties into some of the reasons that there have been many viewpoints on the State of Israel, in many of the mystical sources they actually speak about the fact that the outlines of of the land of Israel are going to expand and that the State of Israel, the land of Israel, is a consciousness, an awareness of God in everything we do. And anyone who’s been privileged to live in Israel knows that you step there and you’re blown away.

I remember moving back from Safed, which is the most kabbalistic mystical city, to Brooklyn. And I was just on the train now and I remember: I was on the train and I felt like instead of God being around me, it was like a brick wall. Like I felt the massive shift in reality. And so in the mystical sources it really speaks about the idea that Eretz Yisrael is a consciousness and when Mashiach comes, that consciousness is going to spread and fill the whole world. And so that’s why in the Chabad tradition there’s the idea of making this place Eretz Yisrael. Wherever you are, bring that reality, bring that consciousness.

LEVY. But Maimonides does talk about sovereignty over the state of Israel, [he] talks about malchut, [he] does talk about a kingship, [he] does talk about a political entity.9

GREEN. Yeah, yeah, I mean absolutely there’s going to be a king because Mashiach is Melech Hamashiach, the king Mashiach.

LEVY. And that will happen in Israel.

GREEN. Yes.

LEVY. So if we’re moving, if the state of Israel is a step in that direction. That’s the question.

GREEN. Oh, is it part of the Messianic unfolding?

LEVY. Yeah.

GREEN. So personally, I absolutely think so. I think that whether or not we see, like what I was saying, the more consciousness element of it, practically, absolutely. I mean, I was, although I was there running a birthright trip once. I was at a kibbutz for Shabbat and a woman came to me and said, and we were speaking about Mashiach, and she said: “Well, I live in Mashiach. This is Mashiach; it’s already here.” We were arguing with her, like what about all the Jews somewhere else? She’s like, no, in Israel this is it. And so I feel that tension of yes, Mashiach, like there’s this Messianic unfolding. And before I was more deeply in Chabad I loved reading the writings of Rabbi Kook and about this national awakening.10 And it’s not my [path]. I think we each have, like it says when the sea split: There were many, many different paths and each tribe took their path. So for me that’s not necessarily my path through statehood as the Messianic unfolding, but I certainly appreciate and see that.

LEVY. So what do you see as the greatest challenge facing the world today? Or what is one of the challenges?

GREEN. What is one of the greatest challenges? I’m of two minds on this because I feel like the two things that arose in my mind are a little bit mutually contradicting, but one is the ability to see truth, to challenge our assumptions constantly, to be realigning ourselves with truth, and just to know what truth is. I think that’s very, very foggy in the world right now. Coming from my background of feminist theory, there was a concerted effort on the part of post-structuralism to denigrate truth as something that is used by people in power to control reality. And so in many kinds of, of the more liberal West, truth has this kind of nefarious connotation. If you’re claiming a truth, like what does that mean?

LEVY. Because people exploited things under the name of truth.

GREEN. People exploited it or it also created delineations that excluded some people. And so when I think of the Hebrew word emet, which, in the alphabet it’s from the first letter to the last: alef, mem, tav –

LEVY. And the middle one is mem.

GREEN. And the middle one is mem, right? The middle of the letter of the alphabet. And so emet is something that never changes. It is always true in every situation. And so I think that even if we identify as religious Jews, if we encounter something [that] doesn’t feel like emet, doesn’t feel like truth, I think the issue is, instead of fighting with it or ignoring it or saying that’s just that community, to actually allow yourself to dig deeper and use that as an opportunity to try to understand something further.

Which I think actually leads me to the second thing that I was going to say, which is the polarization in the world, which is very personally painful and difficult. Like even [within] my own family I have people that believe totally different things. And you know, many, many people have spoken about this. But I think it’s never enough to talk about it because it’s so deeply challenging. But what’s interesting is on a mystical level, God did create a paradigm in reality where there always is going to be friction between two different dynamics. And you know, I remember reading one time in Hasidic discourse and it was saying even deep, deep into the very essence of God, there is God before the tzimtzum,11 before the concealment, and after, and even before the concealment of God within God, there was the thought of concealing Himself and then before. And so even as we think of God as one, Hashem Echad, God is one. And it’s true. But even in that oneness, there is this constant dynamic of two opposites being forced –

LEVY. Polarization.

GREEN. – but being forced to produce a third. And that’s what we need –

LEVY. Antithesis leading to synthesis.

GREEN. Synthesis. Yes, exactly. And so it feels now as if we have this very powerful Messianic energy in the world, and especially the awakening of the Jewish People after October 7 and kind of on the political front this intense polarization, [where] we have a moment that can destroy us or we have a moment where we we can create that synthesis. And so that takes each one of us looking for truth honestly.

LEVY. So how has modernity changed Jewish mysticism?

GREEN. Hmm. The first thing is the process of translation and mediation. Because if you go back to my first answer about what is Jewish mysticism, kind of on a more academic approach, it’s esoteric. It’s something that is only for a select group. We have the idea of the four rabbis going into the Pardes,12 the garden, and only one of them survives because to come face to face with God is an impossible, impossible thing to do. Moses is offered to see Hashem’s, God’s, face and he says: “No, that’s terrifying.” And so what modernity has done is that over time we’ve gone to a place where Jewish mysticism has been mediated and translated through not just language, but through so many thinkers and so many different perspectives, that we can now all approach Jewish mysticism in a way that is bite-sized, you know? And I’m not against social media clips about Jewish mysticism. I think it’s great. I think that that can be an entry point for people.

LEVY. We should make this a clip on social media.

GREEN. Sure. That could be an entry point for people. I think the danger is when you think the peel is the fruit. That should be an entry point and not your whole meal. But what modernity has allowed us to do is spread the teachings of Jewish mysticism beyond what we could imagine.

But the second part is that we now have a much, much broader understanding of the world itself. And when mystics understood the world as it was in their shtetl, in their community, in their own inner world, it had certain characteristics. But now that we could be mystics in the global world, what we can do, like I said before, if the world is an expression of God, we can start to understand the diversity and the variety of how God expresses Himself in so many more ways and so much more of the world becomes open and unfolding to be included in the Messianic process.

LEVY. What differentiates Jewish mysticism from other mystical traditions or mysticisms?

GREEN. Hmm, okay, interesting. I guess the academic in me says each one would be different and I hate generalizations. There’s this classic claim [that] the East is transcendent and the West is material and Judaism is right in the middle. I think there is a truth to that but I also think that there have been many mystics in different traditions that have all sought to have that experience with God. You know, one of my favorites before I was really religious was the classic poet Rumi and he’s a poet from the East who would speak about this passionate love of God and it really resonated with me. And when I encountered Jewish mysticism, what I realized is that we have a mysticism that is a direct connection to God, but like I said before, it’s a received tradition and it comes as part of a package. So we get not just the soul of that experience but also the body, and we incorporate both of them together. And so we see in some of the more new age spirituality a total fleeing from the body of religion and the spiritual element. And in Judaism we don’t – authentic Jewish mysticism cannot be separated. And [we] saw the Sabbatean movement of Jewish heretics that sought to take the teachings of Jewish mysticism and defy the laws of Judaism. So what we have is the merging of body and soul. And so I guess I am saying what I said before of the East and West and we’re in the middle, but I have to do some more research to see if it’s completely accurate.

LEVY. Beautiful. So you made reference to when you weren’t religious. Does one need to be religious to study mysticism?

GREEN. It’s a good question. I think the word religious is not necessarily what I would use, but I would say there is a context within that allows for Jewish mysticism to be experienced in a way that is aligned with the whole scope of Jewish life. And when it’s isolated too much from that broader perspective, that broader communal experience, I think it can be used in ways that are not entirely aligned in what its goal is. And so the question I think becomes what is it being used for, for the person themselves or as a pathway to God. And then it has to be on God’s terms. And so on some level, yes.

LEVY. Wow. And can it be dangerous?

GREEN. I don’t know if in [this] day and age people are going to the kind of places of consciousness that are that dangerous.

LEVY. Like you referred to the Pardes, walking into that orchard. So you think [in] this day and age it’s not like that.

GREEN. I don’t really think so. I mean, we’re just coming off of the holiday of Purim and the idea of drinking until one is at the state of ad delo yada,13 of unconsciousness, of not even knowing. On a mystical level that means reaching a place where one doesn’t know the difference between Mordechai and Haman. And that, on some level, is absurd to think. Not knowing the difference between the Jews killed in the ghetto and Hitler, what does that even mean? So there is an idea from the original seeds of Jewish mysticism that if one reaches that place, it could become nihilistic, like, well, if everything is God, then there is no morality. And I think that could be one of the ideas, one of the dangers, of kind of delving into this. But I think there are so many safeguards against that and also that unless someone is really powerful [enough] to experience that place, I think it is unlikely.

LEVY. So also on this journey, just in this conversation you’ve mentioned your parents, you’ve mentioned your kids. You know, the practical sort of relationships in your life. Do you feel that Jewish mysticism has influenced your relationships in a practical sense? And do you have one example to share?

GREEN. Absolutely, yeah. I’d say in general, I try to not let a week go by without learning something. What it does is it helps me look at the world, like I keep mentioning about body and soul because sometimes the people in our life, we can experience their body more than their soul, especially little kids. We can be bogged down in the physicality of the diapers and the changing and the carpool. And what that allows me to do is to look at them in moments and remember: that’s the soul, that’s a neshama. God has given me a little piece of Himself to guard, to raise, to take care of. And it gives me such a different kind of nuance to my relationship. But I will also say that I draw upon the teachings of mysticism when there are challenges in life. That’s where they become the most practical.

For example, marriage is very difficult sometimes. You have two people with different opinions. Recently my husband and I just fundamentally just saw something differently. And we kept going back and forth and we would just reach this point where we’re like –

LEVY. The sun and the moon.

GREEN. The sun and the moon. [My perspective was], I think I need more emotional support. [His perspective was], you need to figure out practically what to do. And we’re just going back and forth. And at some point I stepped back and I was like, okay, you know, maybe we should accept that we have this difference and it’s okay. And I thought about it, it happened on our anniversary. And at first I was like, oh, what a terrible anniversary. Like, we’ve been married seven years. And then I was thinking, you know what? Then I moved past myself and I started remembering, okay, this is my soulmate. God put me into the world with this person. We overall have an incredible relationship and we go through these bumps. So I think about this concept of a descent for the sake of an ascent. Yerida letzorech aliya. And the whole idea is that we don’t want conflict, but when it happens we can either use it and fall deeper or we can create a false bottom and we’d be like, oh, I’ve hit this point, wait, let me already start going up, let me use this moment as a springboard. And so I’ve had this; this has happened to me over and over again in my marriage, in my relationships with people: to look at challenges and sometimes you get to this dark point where you’re like, I’m not going to get out of this. It’s so difficult. And that, these concepts, these paradigms, they’re that light for me. That sun that comes into the dark of the emuna [faith]. And I remember, oh, this is also from Hashem. This is also from God. And this is actually strengthening the bonds between me and my spouse because now we’re accepting in our relationship [even] when we see things differently, and yet we’re still committed to each other and we’re still bonded. And so now that bond has a deeper element to it.

LEVY. It’s beautiful because the idea of the East and West is applied in the two areas of your relationships. You said with your kids, the messiness of the car pool or the diapers is what exposes that spirituality, and with your husband it’s sometimes those points of friction that underscore the depth of the relationship.

So we’ve talked, really, in practical terms and you’ve brought beautiful teachings. But I’d love to end just with one teaching. What is one idea that has inspired you, or continues to inspire you, that really comes from the depths of Jewish mysticism?

GREEN. I will riff off of that idea of the challenges also coming from God. Because we have this idea, we have this verse, Hashem Hu HaElokim.

And it’s two names of God. The tetragrammaton, yud, keh, vav, keh, the ineffable name of God, which we don’t even pronounce. That’s why I say Hashem, the name. Hu, which means He is, Elokim, which is a name of God’s concealment. It has the same gematria [numerology] as the world, nature.

And so the question is, how can we say the ineffable, untouchable, limitless aspect of God is the same as the constricted, material aspect of God? And so I’ve been recently learning deeper about this and it’s interesting because there are these two stages in the explanation. The first is that Havaya, Hashem, is like the sun and Elokim is the shield.14 And so they work together because the light of God, as He is in an infinite way, can’t come into the world without creating a fire, without just burning it up. And so Elokim is the vessel that the light comes into in order to make the reality of the world practical. Like the idea of taking light from the power station and you want your refrigerator to turn on. So it goes through the power cord. And the light is condensed over and over and over. And so really in the mystical perspective there are many names of God. And this is the dynamic between these two names. Each name brings a different energy of God into the world.

And so [with regard to] the first level of this explanation, how could the ineffable and the practical be the same? One is the source and one is the shield or the vessel that transmits the source. But yet that answer doesn’t fully satisfy because we’re still saying that they have different characteristics. They have different functions. And so they fundamentally are different. So how can we say that Havaya Hu Elokim, they’re the same?

So we have to go a little bit deeper, which is that the ability, the aspect of God that is in Hebrew bli gevul, without boundaries, we more readily associate with Godliness because we think of God as abstract, spiritual, beyond the world. But to say that that is more God than the part of God that is within boundaries actually diminishes God’s infinity, God’s ability.

LEVY. That actually puts a boundary on God.

GREEN. Yeah, like, oh, you can be a spiritual God, but you can’t be practical. You can’t be concealed. That’s like a lesser part of You. And what this teaching is actually revealing is that, no, Havaya, the ineffable, the bli gevul [limitless], is the same revelation as the bound, concealed part of God.

LEVY. Amazing.

GREEN. It is not [that] one functions as a barrier for the other. They are both the same manifestations of God and they come out from the receiving end in different ways. Just to go back to masculine and feminine, we experience mashpia – mekabel, male and female, as different from our perspective. But from God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same. Their value is exactly the same. And so in this teaching, the idea that when God is revealed in your life, when my mom found the high chair and I was like, thank you God, this is such a great feeling. And when I’m having an argument with my spouse and I’m like, where is God? Why? Hashem, why are you doing this to me? This is so terrible. But –

LEVY. But both are the same God.

GREEN. No, they’re exactly the same God. And it’s the same love for me that God is expressing. And so when I’m in those moments, and my husband and I had a whole farbrengen [Hasidic gathering] unpacking this afterwards, the next day we were like, we need code words to be like Hashem Hu HaElokim. When we’re in a period of struggle, you know, when business isn’t going well or when the kid is sick and I have to stay home for three days, whatever the thing is, when I’m in that period of struggle Hashem Hu HaElokim. This is exactly the same revelation of God when I’m praying in shul [synagogue] on Rosh Hashana, which I also can’t do because I have all my kids, but when we have those manifest moments of God, they’re really one and the same.

LEVY. Well, what’s really interesting is we say that verse seven times at the pinnacle of Yom Kippur. Yom Kippur is the most spiritual, so to speak, day where there are no marital relations, no physicality, no eating, no drinking. There are so many different things that we go away from and we just go on the spiritual, so to speak. And yet that pinnacle is really the moment when we’re about to go into Maariv [the evening prayer], we’re about to break the fast, we’re about to go into the physical life. And perhaps the message is that this height of spirituality that you just experienced is the same height of spirituality as [when] you go into regular days and then into Sukkot and then into normal life. And it’s a motif throughout this conversation and I give you a blessing. Really, what I said before [regarding] when you prayed by the grave of the Lubavitcher Rabbi and you asked what should you be doing in life? I think that the answer is very clear. It’s not your shlichut, i.e. your mission of Godliness versus your academia. It’s that your academia is an expression of your mission and it’s been an honor to witness this from afar, to share this conversation from close, and we give you a blessing that you can continue to share.

GREEN. Amen. Thank you so much. Thank you for having me.

LEVY. Thank you. Thank you.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Rav Moshe Weinberger: Can Mysticism Become a Community?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rav Moshe Weinberger, rabbi and educator, to discuss the role of mysticism in modern-day Judaism.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Anita Shapira: ‘You cannot wipe out Hamas’

Leading Israel historian Anita Shapira answers 18 questions on Israel, including destroying Hamas, the crisis up North, and Israel’s future.

Recommended Articles

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

5 Lessons from the Parsha Where Moshe Disappears

Parshat Tetzaveh forces a question that modern culture struggles to answer: Can true influence require a willingness to be forgotten?

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why We Need to Live With Radical Laughter This Purim

Brother Jorge asks: Can we laugh at God? We might answer: We can laugh with God.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Religious Zionists Taught Me About Reading Tanach as a Living Story

In Israel’s Religious Zionist world, Tanach is not only a way to understand contemporary Jewish history—it is also a guide for the…

Essays

A Jew in the King’s Court: Dual Loyalty in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther suggests that diaspora is not merely a temporary or anomalous state but an integral part of Jewish history…

Essays

Letting Go of the Scary God

Changing how God appeared in my life began with changing how God appeared in my mind. I needed to let go of…

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

The New Tower of Babel

Watching AI spread through every corner of life raises an unsettling question: What kind of world are we building for our children?

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Five Years of 18Forty

18Forty helps users find meaning through the exploration of Jewish thought and ideas.

videos

Torah Study and ChatGPT: How Should Jewish Education Respond to AI?

On this 18Forty panel, we speak with Alex Jakubowski of Lightning Studios, Sara Wolkenfeld of Sefaria, and Ari Lamm of BZ Media…

videos

Moshe Gersht: ‘The world of mysticism begs for practicality’

Rabbi Moshe Gersht first encountered the world of Chassidus at the age of twenty, the beginning of what he terms his “spiritual…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…