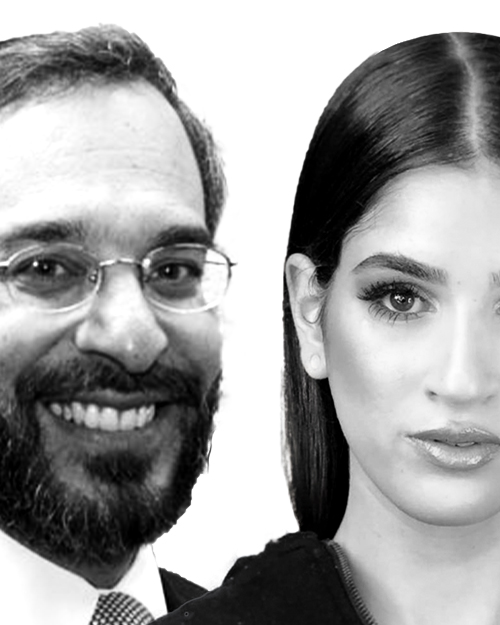

Suri Weingot: ‘The fellow Jew is as close to God as you’ll get’

Suri Weingot joins us to discuss the closeness of redemption, godliness, and education.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

What does it mean to experience God as lived reality? Mrs. Suri Weingot reframes spirituality not as something hidden or elite but as something pulsing through every blade of grass, every Hebrew letter, and every human relationship.

Mrs. Suri Weingot is a senior educator in TMM High School and gives classes and lectures to women across the community. She runs a community mentoring program that enables women and teens to contribute their time and heart by impacting the lives of the next generation.

At its heart, this is a conversation about love of Torah, of life, and of every person. Suri joins us to answer eighteen questions on Jewish mysticism with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy including the closeness of redemption, godliness, and education.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Suri Weingot, it’s a privilege and pleasure to be sitting with you here today here in the beautiful mountains of Eretz Yisrael, of the Land of Israel. When I asked how you’d describe yourself, you said an educator, a teacher, a mora, and that really goes to the essence of who you are for high school, for post high school, for the congregation of Aish Kodesh that your family founded. Thank you so much for being here.

MRS SURI WEINGOT. Pleasure, thank you for having me. It’s special to be here. Thank you.

LEVY. So what is Jewish mysticism?

WEINGOT. I guess if you ask those who know [they] don’t say and those who say don’t know. I’m going to put myself in the “those who say don’t know” category. I’ll share about Pnimiyut HaTorah, if you want to, under the umbrella of mysticism [that] is the kind of things that sometimes feel hidden and we want to pull them out and bring them up. I’m a lady, I’m going to give all my examples as relating to housekeeping and life at home. I don’t know if you know what a duvet cover is. You know what a duvet cover is?

LEVY. Of course, I use one every evening when I go to sleep.

WEINGOT. Okay, fine. So I don’t know if you help with the duvet covers, but I remember when I got married trying so hard to put the blanket into the duvet cover and I was crawling inside the blanket trying to find those corners and then crawling out, and I’m shaking and it was a ball of mess, and it’s too big and it’s too small, nothing’s working. And then my mother-in-law comes over and I go, Ima, help me with these duvet covers. She goes, Suri, you’re doing it all wrong. You have got to turn the cover inside out. Then it’s very, very easy. You place the blanket exactly [in place] because you see it from the other direction then you give a little shake.

As I’m sharing, if you know what I’m talking about, you know what I’m talking about.

LEVY. I know exactly what you’re talking about.

WEINGOT. And if you don’t, go home and help with duvet covers, right? Sometimes we think that we have to [understand things] outside in, but it’s inside out. We have to go inside out. Pnimiyut HaTorah is making sure that we get it right from the initial get-go. I look deeply into the shoresh of what I’m doing, to the source of what I’m doing and why I’m doing it, and then things go nicely. They slip on much more beautifully. It’s much more complicated if we’re so busy trying to find spaces for the corners in our lives on a halachic level or on a maaseh level.

LEVY. Very practical or Jewish law.

WEINGOT. Exactly. If we don’t start by turning a little bit inside out.

LEVY. Is there an example you have of turning inside out the Hebrew letters? I heard you know a bit about the Hebrew letters.

WEINGOT. Sure, I mean listen, everything’s the Hebrew letters. It’s the alef-bet. Bereishit bara Elokim et, you know, everything’s alef to tav.

LEVY. It’s alef to tav, the first to the last letter.

WEINGOT. Exactly. You know, my favorite part like this is a good example by the way, you know, I teach high school girls the alef-bet. So until they come to eleventh grade, alef meant wherever they left it in pre-1A honestly, wherever their mora pointed on the top of the of the chart: komatz alef ah, etrog, bet bayit, gimmel gamal.

All of a sudden like, pshh, whoa! They’re never going to look at an alef again the same way. Now look, there is a time and a place for everything but they could have been introduced to that younger, and then they’re going to see the word bayit and they’ll look at the bet and say, ah, it’s an open home. Oh, I get it. The bet has an opening towards the gimmel. The gimmel‘s the gomel, the giver. The giver’s walking to the dalet, his legs, the gimmel‘s leg, is moving to the dalet. The dalet‘s the poor one. The dalet needs the gomel.

LEVY. From the word dal, which means poor.

WEINGOT. Exactly. Dal means poor. A gomel, a gimmel means to be, to give. Exactly. And the dalet though, what is the dalet moving towards? The dalet, if you watch where he’s moving, he’s moving to the hey. Hey is HaKadosh Baruch Hu.

LEVY. That’s God Himself.

WEINGOT. Exactly. So every dal knows that he’s giving, but all the giving goes back to the one who is receiving; he knows that it’s all coming from the hey. It’s all coming. And the difference between the dalet – the dalet is echad, right? If you take away that little yud of humility, it’s acher. We could give credit to everybody but echad if we’re not humble.

LEVY. Acher being the other, echad referring to the oneness and unity of God.

WEINGOT. Exactly, exactly.

LEVY. And the yud and the tav, the end of the bayit, how does that tie into bayit?

WEINGOT. Oh, it’s a long drasha, there is a lot.

LEVY. But the beginning is huge.

WEINGOT. Yeah, but you see as soon as we open up our students, ourselves, all of a sudden everything has so much more meaning. Everything’s so much bigger because the alef-bet is the one thing where you’ll say there is no more to it than meets the eye, right? It’s what allows me to learn. No, they themselves are teaching you. The letters are speaking to you. Well, everything is speaking to me. The gimmel, it’s a gamal, it’s a camel. The camel’s speaking to me. What’s the camel saying in his shape, right?

We have to have eyes that we need to learn, I believe so deeply, when we’re very, very young. I know, there’s so much talk on adult education – am I rambling?

LEVY. No, it’s beautiful. I like that because what you’re basically saying is that you’re building a home, the bayit, that’s the example you gave, when they’re already a child. You can’t build a home when they’re twenty-five.

WEINGOT. Right!

LEVY. You build the home when they’re five, when they’re learning those letters.

WEINGOT. Right. So with all the talk of everything that’s being discussed now and adult education it starts with the babeluch [little ones]. It starts with the language that we use in our home. It shouldn’t be a chiddush.

LEVY. It shouldn’t be some innovative new thought.

WEINGOT. No, no, no.

LEVY. So that leads us to the next question. You spoke about Pnimiyut HaTorah, mysticism, as going inside out. You grew up in the home of Rabbi Moshe Weinberger and Rebbetzin Weinberger. We discussed this personally before. But what is your origin story with mysticism? Was it taught by them? Is there an encounter in your life that turned you from a mekabel to mashpia, that turned you into someone that really wants to give over this unique type of Torah?

WEINGOT. I’m not going to give you one moment per se. I’m still waiting for my moment. There are more to come, right? I don’t have my transformative moment. I have so many moments, but I could certainly share with you something specific that continues to guide me, and when I want to remind myself of my mission I play this song over and over when I need chizuk.

There is a beautiful songwriter-singer Michael Shapiro, he’s now becoming a little more known in the world because a lot of good people have been trying to get his stuff out there.

LEVY. They just put an album out with him.

WEINGOT. I heard, I know. I don’t have a smartphone and I don’t have any WhatsApps or anything so I depend on everybody else to tell me when something good is coming out. And it was such a mazel the other day. I had to borrow somebody’s smartphone because I needed Waze to get somewhere and my machine was broken. And I put on 24Six [the streaming platform] and it pops up. Moonlight. It was that day, it was Thanksgiving, and it must have just come out my whole ride there and back. And then I’m like, dad, how come no one told me? How come I didn’t know? Everyone knows they’re responsible to tell me when good things are coming. But I found out, he’s like, no, no, it just came out that day. So now people might know. If they’ve heard it, they might know what I grew up with.

So I was driving with my father and my sister back from a Yom Kippur program. We had gone to the country for Yom Kippur. My father was involved in – I don’t remember what program it was. And he took me and my sister along, probably to make Yom Kippur easier for my mother. I was a little kid, you know? And on the way back we’re listening to music in the car.

So I’m listening to it in the car and I’m not going to sing for you now, obviously, but the words that Michael Shapiro sings start: Look into the summer night sky from our whirling world and hold on to a thought of forever. And that’s the low, right? And then the music gets higher and higher and higher and it goes: And servants’ worlds making rounds in motions too profound to know, expressing holy harmony and voices raising prayers of love from all life’s seen and unseen to the Holy One blessed be He. And he keeps repeating this, right? And voices raising prayers of love and and the music gets higher and higher and higher.

And I remember, I was a little kid, I thought I got ruach hakodesh. I was in the car and I was listening and something happened to me. And I wouldn’t tell my sister, she would make so much fun of me.

LEVY. Now she’s going to hear about it.

WEINGOT. I know, it’s okay, she always made fun of the way I got into my music, but she was the older sister, she has to make fun of me, right? But I remember [thinking] I’m not saying anything and I’m not even going to tell daddy in the front. And I looked and I put my head against the windowpane and I wanted to look into the summer night sky and hold on to a thought of forever. I was so young. And I was looking [out the window] the [entire] ride home, [thinking] can I see the malachim in circles dancing?

LEVY. The angels.

WEINGOT. I want to see the angels making rounds in motions too profound to know.

And that is certainly something that I hold on to if you want to give a moment to [the thought] that there’s so much more going on all the time and to tap in to looking into the summer night sky and pondering eternity. That was what got me, that is what got me feeling so strongly about, I guess, our mission here.

LEVY. Well, by the way, that is how Abraham, how Avraham Avinu –

WEINGOT. Very beautiful.

LEVY. – connected the first time.

WEINGOT. So there you go, you’re right.

LEVY. And he had to see there must be more to life than this.

WEINGOT. You’re right.

LEVY. He looked beyond, God even took him outside of the world to be able to see that infinity.

WEINGOT. So true. That’s great. Thank you. Now I feel like I just [was] doing what we were expected to do.

LEVY. You’re looking in the same direction as Avraham.

WEINGOT. Look into the summer night sky. That’s nice.

LEVY. So should all Jews be mystics? Should we all be learning Pnimiyut HaTorah?

WEINGOT. Yeah, sure. I mean, listen, that’s why I’m being mindful. I’m not saying everyone [should] open up books of Kabbala. Pnimiyut HaTorah means the wise, it means that there is ratzon Hashem pulsating. God’s desire is pulsating. The world is alive. So everybody has an obligation to know that and see that. Everyone.

My mother-in-law is a very special lady. She loves grass and trees and I remember once I was sitting outside with her mindlessly and I pulled a piece of grass and she … she gasped. She gasped. “Ah! It’s alive, Suri, it’s alive!” Like oh, she’s so machshiv. She’s so machshiv the godliness inside a blade of grass.

LEVY. She recognizes –

WEINGOT. Yeah, that it was alive. That’s Pnimiyut HaTorah.

LEVY. Well, Hassidut talks about, I mean there are beautiful texts about angels that are whispering to each single blade of grass.

WEINGOT. Yes. They’re telling them to grow. And who am I to step on an ant or to pull a piece of grass? Life, chiyut, is pulsating with ratzon Hashem. So who is allowed to say it’s not for me? We make Birkat HaIlanot, right?

LEVY. Say a blessing on the trees.

WEINGOT. Exactly.

LEVY. So that blessing is to recognize godliness.

WEINGOT. Shello chasar be’olamo klum. It’s my favorite bracha. Rak lehanot bahem bnei adam. He created it for the human’s pleasure. What’s pleasure? Lehitaneg al Hashem. There is nothing more pleasurable than seeing godliness in your hamburger and your blade of grass. That is Pnimiyut.

LEVY. Amazing.

WEINGOT. Yeah.

LEVY. It’s the inside of the duvet cover.

WEINGOT. Exactly.

LEVY. So you talk about godliness, you talk about seeing God, the hand of God. What is God?

WEINGOT. We are Tzelem Elokim. What is God?

LEVY. I mean, do you have a vision when you pray to God, when you think of God, when we say that word or different words that describe Him?

WEINGOT. Yeah, well look. I remember sitting in a class actually on the Neve campus with Rabbi Refson. And he said that he finds a lot of people are struggling when we talk about Him as a loving father. Because those that didn’t have a loving father don’t understand what a father figure looks like, right? So Hashem has given us a lot of different meshalim down here –

LEVY. Parables.

WEINGOT. – to work with based on what works best for us, right? Melech is a tricky one. I don’t love talking to students about kings and queens. And then they go, if you’re ever in England, I don’t know what this king is looking like, you know, like okay, of course. Malchut, we have to elevate that a little past the princess in England, right? But so, you know, everyone’s God and the pesukim speak to us.

But so I could just share with you Memale kol almin vesovev kol almin umibaladecha ein shum metziut klal.

LEVY. How would you translate that?

WEINGOT. Hashem, You fill all worlds, You surround all worlds, there is no metziut that isn’t You.

LEVY. No reality.

WEINGOT. There is no reality. Hakadosh Baruch Hu is our reality. And anything that feels like a reality, that means we are tasting godliness.

So when we feel more alive than ever, that is Hashem. That is God. So if that music, or that dance, or that shiur, or that landscape, or that person makes you feel alive in a way that feels more powerful than you feel sometimes in other moments of life, ah, Ki imcha mekor chayim.

LEVY. The source of life.

WEINGOT. The source of life. So when you feel alive, and then look, someone could say I feel alive and then they feel more alive, like ah, I thought I felt alive but I didn’t even know. We should keep strengthening what is the most joyful – I remember reading the Bushes, Barbara and George, at 100 years old, I don’t know if both of them did, maybe both of them skydived at a 100. They wanted to feel alive. Everyone’s got what makes them feel alive, you know? But when you feel most alive, let yourself understand why you feel so alive.

LEVY. I also like that because you feel so alive but also there are also times when you feel more alive because God is infinite. So you’re never going to completely encapsulate it all, but you at least appreciate that moment when you feel that life force and then you feel it again.

WEINGOT. Right, right, right. And also you taste chiyut, then you say, okay, there’s nothing that feels more alive than life, and there’s nothing more alive than Hashem. So He’s chiyut. That’s it, you know?

LEVY. Endless life force that animates everything.

WEINGOT. Exactly.

LEVY. So what is the purpose of the Jewish People then? What are we here to do?

WEINGOT. So there we go, to make sure that this world is pulsating with life. To bring light, to open and uncover what it’s all about, you know? To just make sure the Lubavitcher Rabbi – one of my favorite books is Positivity Bias. It’s pretty new, but the Lubavitcher Rabbi, he saw every single chiddush that came out was just –

LEVY. Every new thought.

WEINGOT. Every new thought, every new invention, every birth of anybody, anybody that was becoming a somebody, they are here to further Hakadosh Baruch Hu and Am Yisrael‘s mission on this earth. So Am Yisrael‘s job is to take everything as it comes and open it up and peel it to reveal the light. To reveal Him.

LEVY. So how does prayer work then?

WEINGOT. Well I think there’s a lot of different parts of tefilla. Vaani tefillati.

LEVY. I am my prayer.

WEINGOT. I am my prayer. Prayer is – my goal, my tachlit, my opportunity is to speak Hashem’s words and to reveal His words. And I think tefilla, if we’re paying close attention as we speak, it’s like every school they’ve got their mission statements. You have to remind yourself of your mission statements, right? Tefilla reminds me of my mission statements. Tefilla is my mission statement. You daven, you open yourself up to formal or informal conversation with Hashem.

You know they say now couples need date nights, and then now they say, oh couples, they need to get away on vacations, everyone’s got their own style. And sometimes I’ll laugh, I’ll say maybe, maybe that’s what you need, but maybe every night we have date night. Maybe our home is my vacation spot, right? Maybe we talk so much, what do you know, right? So tefilla is date night every night, tefilla is a honeymoon getaway every day, right?

LEVY. It’s a rendezvous with God.

Suri Weingto: Exactly. Exactly.

LEVY. And then what’s the goal of Torah study?

Suri Weingto: The goal of Torah study, well like I shared before, it’s the or of Hakadosh Baruch Hu.

LEVY. The light of God.

WEINGOT. It’s the light of God. Torah study is both sides of the duvet cover if we’re back to our duvet, right? It’s the inside and it’s the outside, it’s the ot and it’s the white parchment that holds the ot. I mean Torah study is the map, it’s the full map. Now they’ve got Waze that directs you, then it redirects you, and then it redirects you again. Here’s traffic, go this way, there are so many different directions you could get so farblondjet [lost, befuddled, or wandering]. And I still do get farblondjet, but when they say there’s seventy ways [to interpret the Torah], there are, taka, seventy ways, and you can’t get farblondjet, you know, follow, follow.

LEVY. I love how you keep coming back to the duvet because it keeps you warm. And it’s not just the inside out, it is what the Torah provides us, that is the subtext. So does Jewish mysticism view women and men as the same?

WEINGOT. Yeah sure, I mean men and women are the same.We’re talking about neshamot here. If you’re talking about gilgulim, female doesn’t necessarily remain female, male doesn’t remain male, it’s qualities and traits.

LEVY. In terms of the journeys of reincarnation.

WEINGOT. Yeah, you know, kids love asking that stuff in school, right? They love that because I think we need to teach a shtickl more Pnimiyut. We gotta teach a little more Pnimiyut, otherwise when you have a question and answer with the rabbi it’s like, tell me about my reincarnation because everyone gets excited about something. But sometimes we limit male and female because we think of them as gender. Male and female are traits and qualities that we need to make sure to interact with, always. There are times for gevura and there are times for chesed.

Of course as we come closer to Mashiach we’re seeing the feminine traits are very important. Ahavat Yisrael, which is conversation, certain female traits that certainly men have been more comfortable with now, and there are certain male traits that women are becoming more comfortable with. So I don’t think Hashem, zakhar unekeiva –

LEVY. Bara otam.

WEINGOT. Exactly.

LEVY. Male and female He created them.

WEINGOT. Yeah, exactly. I do find Lashon Hakodesh to be amazing in that –

LEVY. The Hebrew language.

WEINGOT. Yes, the Hebrew language is so fascinating because now if you go into a store and I say to somebody “you,” it can be very appropriate because I’m asking you for: Can you help me? It’s a tricky world, you know, and I can keep it very –

LEVY. Gender neutral.

WEINGOT. Gender neutral. Lashon Hakodesh doesn’t allow you to do that. It’s lach or it’s lecha. You have to identify the midda as male or female, right? There’s Shechina, Shechina is female, HaKadosh Baruch Hu is male. If we pay close attention, the world is divided into zachar venekeiva attributes. So by Hashem, I don’t think the distinction is where we need to use different qualities to bring out what’s necessary.

LEVY. And should Judaism be hard or easy?

WEINGOT. It’s a great question. You know I like that question. So often I hear people talking about like, ameilut baTorah, you know?

LEVY. Toil in it.

WEINGOT. Toil and toil. And I have to tell you, I can’t really buy my husband presents. The only gift I could get him is to say stay out all day and learn, right? It’s his favorite thing in the whole world. My father’s favorite thing, my husband’s favorite thing. It’s candy, it’s sugar. Send me to a massage, but my husband wants to, all day, all he just wants to learn Torah. So I should be zocheh [meritous] to find it like a massage. But I think that it should be both. I think it should be hard in the sense that we always need koach [strength] to pull ourselves out of the craziness and remind ourselves of our tafkid and our tachlit. That can be hard.

LEVY. Of our role and of our purpose.

WEINGOT. Yes, our role and our purpose. We can get easily stuck on a treadmill because of people that we’re sometimes surrounded by or because of expectations or certain goals that we place for ourselves that are not lofty goals and just the regular day-to-day life. It can be easier not to be mindful and aware and present and so on.

So I think that can be hard, that’s where it can be hard. It’s hard to get into a pool, but once you’re in it, there’s nothing more delicious, right? Because then you say this is the best thing ever. I’ve never felt better. I can’t believe I’ve lived my life without this until now. But it can be hard to jump into a pool.

LEVY. So why did God create the world?

WEINGOT. God’s a giver. This takes a lot of time. God’s a giver and He wants to bring His light in the most giving, beautiful way. And we haven’t yet seen it. We’re going to get there.

LEVY. But He started the process.

WEINGOT. He started the process. I think when we get to redemption, we’re going to know why He created the world. We’re still working towards that. We still have a lot of whys.

LEVY. So on that journey, can we do anything against God’s will?

WEINGOT. Well, He certainly gave room for the human struggle, but that’s also His will.

LEVY. Sounds like a paradox to me.

WEINGOT. Yeah, it is.

LEVY. So you said when we get to the end of days, what do you think about when we say the word Mashiach? What does this look like? What is that reality?

WEINGOT. You know, different times, different things. But my favorite vision of it is [like] when I love to sit in the Old City and you see children holding hands and they’re skipping, and you see old men and old women, and od yeshvu zekeinim uzekeinot birchovot Yerushalayim, right? Urechovot ha’ir yimaleu yeladim veyeladot mesachakim birchovoteha. That we’re going to have the old men and the old women and the children dancing and singing in the streets.

I think no dance and no song is complete right now. But to me, the dance and the skipping of the young children and the old people, that means you’re not going to have the old people feeling down because of the pain of life. You’re not going to have the young children, unfortunately now, who also are not skipping the way, maybe, they used to skip because of the pain. It’s going to be the most glorious revelation of all times and it will bring to unbelievable joy. Kol chatan vekol kalla. I’m seeing the streets full of weddings and of children and of old people and there will be plenty of room for everybody.

LEVY. What’s beautiful is you described the reality that exists.

WEINGOT. We’re getting there.

LEVY. You’re in the Old City and you quoted the verses from the Bible that actually describe this. So is the State of Israel part of the final redemption? Is it part of that process?

WEINGOT. We’re getting there. Look at what’s opened up to us. I mean, I think Hashem is giving us peeks. We’re coming close to Chanukka, and there’s nothing more exciting for my kids than when they see that I have wrapped presents hidden under the bed, you know. So they can take all the guesses they want because they see the sizes and the shapes, but they’re already borrowing from future joy. And they’re so excited for Chanukka. I like to do it early because I want them to build up their joy. So I make sure to do that very early on.

I think Hashem has been giving us a lot of gifts in the State of Israel right now so that a lot of what is going to be, we’re already slowly unwrapping it. But we ain’t seen nothing yet. We’re getting there, you know.

LEVY. Exciting.

WEINGOT. Yeah, it’s going to be amazing.

LEVY. So what’s the greatest challenge facing the world today? You’ve got many unique perspectives and one of them is really teaching the next generation. Do you see a major challenge?

WEINGOT. Major challenge facing the world today? Yeah, well I can only share from my perspectives obviously as a teacher, as a teacher of mostly teenagers and a mother of mostly teenagers. People want the gold but they don’t know which shovels they need to use to get there. And they don’t know that there’s a process and it’s going to feel very wonderful if they’re given the right tools and they start digging.

The Lubavitcher Rabbi talks about the earth as a metaphor. The best of it is down deep. There are natural resources also in the pebbles and in the stones. You dig a little more, you get to the – you know my husband gardens so he can speak more [about] it but the mud that’s got even more going, you know? Dig a little deeper. You’re not going to find it in Woodmere but there’s gems, there’s gold, right?

So a lot of the kids are getting tastes of it but they don’t quite know which tools are available. They don’t even know that they’ve got a toolbox available and they don’t know the instruction manual for what you use to uncover [those gems], right? But they’re so open. The kids are so open. They want to learn so we have to give them shovels. We have to tell them what natural minerals are under their feet and let them explore. Get digging.

LEVY. How has modernity changed Jewish mysticism?

WEINGOT. Oh, there’s much more access. There’s just so much unbelievable access to Torah.

[It used to be that] maybe they were lucky if it was on their Shabbat table or [taught by] their rabbi in their community or their teacher in their classroom. No one’s limited. So everything’s been brought. We’ve got a smorgasbord. It’s all been brought to us. Thank God.

LEVY. And what differentiates Jewish mysticism from other forms of mysticism or other mystical traditions in other religions? What makes it unique?

WEINGOT. I don’t know much about what’s out there but it’s emet. I could tell you it’s emet. If you go into a store, the jewelry store or let’s say the bakery, you start asking questions. Some people like them, some people don’t, right? The bakery that [everyone] likes is the one that has awesome stuff to sell you. So if you say: Where do you get your flour from and what oven are you using? They’re more excited than ever.

The one who’s avoiding the questions doesn’t have so much to – their product’s not awesome. So we’ve got the most beautiful products. The more you dig the more you’ll find about the products that Hashem is serving us.

LEVY. And we’re fully transparent about that.

WEINGOT. Exactly. Because you can be. You could afford to be if you’re selling real jewelry. You could tell them to take it out, study it, bring it to every jeweler they want. We don’t care. Do what you want. We’ve got it. We’ve got gold.

LEVY. So do you have to be religious to study Jewish mysticism?

WEINGOT. No. Pnimiyut HaTorah, learning Torah, learning Pnimiyut, learning the ratzon of Hashem should open up one’s heart to then come to walk and continue on a journey of every area of life fulfilling ratzon Hashem, Hashem’s desires. So you can start wherever you are, wherever you come into the picture. You’ve got to keep the journey going though if you really want to make sure that you are a vehicle for the light of the Creator.

LEVY. So can it be dangerous to study this type of Torah?

WEINGOT. Dangerous? Depends what we’re looking at. I mean it can certainly be dangerous for anybody to think that they’ve filled themselves up if they don’t continue studying ratzon Hashem. That can be dangerous. A false sense of pride is dangerous. A false sense of ruchaniyut, it’s like you could drink a lot of water and think you’re full and you still haven’t gotten all your nutrition. So it’s important to make sure to continuously explore Torah and ratzon Hashem.

And also I do see that it can be dangerous when anything comes with too much intensity where one is. Like we say if you want to talk about going into a pool, you could drown. You have to come up for air. You have to know how to interact with people. It comes down to healthy interactions. And if somebody is not interacting with beautiful refined middot, if they’re sitting there over the books or over their concepts but it’s not translating into how I treat a fellow Jew, that’s dangerous because the fellow Jew is as close to God as you’ll get, and the whole goal of learning Torah and Pnimiyut is to get close to God.

Avraham Avinu said: Excuse me, Hashem, I’ve got malachim here, I’ve got angels to deal with. If we forget about the angels because we’re interacting with godliness, we’re not reaching God. That can be dangerous.

LEVY. So how is it in a personal way? How has it changed your own relationships? You talk about the importance of the effect with your children, with your students, with your parents, with your husband. How has it affected your relationships? Are there any personal examples where you can really see how the teachings have influenced that?

WEINGOT. Yes. I think I’m comfortable saying and I hope to feel this way that I love every single person I talk to. I love them. Yeah. I don’t need to work through loving my students. You could say it’s natural to love children, but I don’t know, it’s – not all the time, you know? But if we walk into a room with our students and our children and our spouse and we say, Hineni muchan umezuman lekayem mitzvat aseh shel veahavta lere’acha kamocha, I now, God, accept upon myself the mitzva of loving a fellow Jew, I think that that is the way in. It’s the way in. That’s it. All the stuff, everything else is shtuyot. Nothing else really matters, you know? It’s the easiest way.

You could have every good class on how to be a teacher. If you don’t love the godliness in the student right away, how are you going to teach godliness?

LEVY. I think that really sums up mysticism because people think it’s something all the way out there. You learn the Baal HaSulam or some of these, it’s all about veahavta lere’acha kamocha. It’s all about loving the other and how you can bring it practically into this world.

WEINGOT. Exactly. That’s it. It’s very easy. It’s easy.

LEVY. Well, it’s not always so easy for everyone.

WEINGOT. No.

LEVY. You’ve got to work at it.

WEINGOT. But it’s easy in terms of lo bashamayim hi velo me’ever hayam. We don’t need to go far and travel wide and engage or interact with specific kinds of people. Of course, that too. Turn to your right, turn to your left, and there is godliness everywhere.

LEVY. Beautiful. So we talked all about these different teachings. Can you share one teaching before we close this conversation that you take with you, that inspires you, that you teach to your students, something that comes to mind?

WEINGOT. So many. There are so many. Okay, it’s less of a teaching and more of a collective approach I find helps me all the time. So we grew up on stories of a lot of tzaddikim, of course, but Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev was the tzadik that I always felt the most connected to.

LEVY. Is that why you named one of your children?

WEINGOT. Yes. My sister actually was in Eretz Yisrael on a trip when I had our son, and she came home before the brit and then she gave me books on Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and she said, “I got them for him.” I said, “Wait one second, but he hadn’t been named.” She goes, “What? You think I didn’t know? Of course he’s going to be named Levi Yitzchak,” you know? She said, you know, I guess she was so confident it was worth a few shekalim, you know? He still has those books.

But what speaks to me most and it was like the Torah of his whole life and I think it needs to be the Torah of our life is that he would look at every action of Klal Yisrael and then turn to Hashem and say, You see that, Hashem? You see your Yidden? You see your people? Look at who they are. Look at them. Look how good they are. This is why we need You. This is why You need to stay. We need You and You need us.

We need to only see the good in another Yid. We need to only see the good in everything like I said before that comes out into this world, every situation, because that’s what Hashem is seeing in us, that’s what we want Him to continue seeing in us, that’s what we have to do.

So I think when it comes to my children, the students, and any teaching, the focus is always finding Hashem in another and that’s through, you know, I think most of Rabbi Nachman’s teachings that inspire me in that way are to always look for the nekuda tova [drop of goodness], always. It’s the first thing you want to pull out of somebody because then we wave that to Hashem. Say, Look, Hashem, he’s one of Yours. That’s the nekuda tova. We need Hashem to do it for us all the time, to find our nekuda tova.

LEVY. Beautiful. Well, I think that it’s very clear just from this conversation, and I know anyone that has listened to this will come out inspired because I know I have. That you see the best in everyone. That is why you’re able to love everyone that you speak to, that you teach, that you learn with, that you connect with, and we give you a bracha. We give you a blessing that you continue to see that goodness in every other person, that God continues to see that goodness in you, and through that we can build those bridges from the real to the ideal on that Messianic Era, on that arc that we’ve described, so that we can truly be one, Hashem echad u’shemo echad, that God’s name can be as one.

WEINGOT. Amen. Amen. Amen. Thank you.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Dr. Ora Wiskind: How do you Read a Mystical Text?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Dr. Ora Wiskind, professor and author, to discuss her life journey, both as a Jew and as an academic, and her attitude towards mysticism.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Debbie Stone: Can Prayer Be Taught?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Dr. Debbie Stone, an educator of young people, about how she teaches prayer.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

5 Lessons from the Parsha Where Moshe Disappears

Parshat Tetzaveh forces a question that modern culture struggles to answer: Can true influence require a willingness to be forgotten?

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

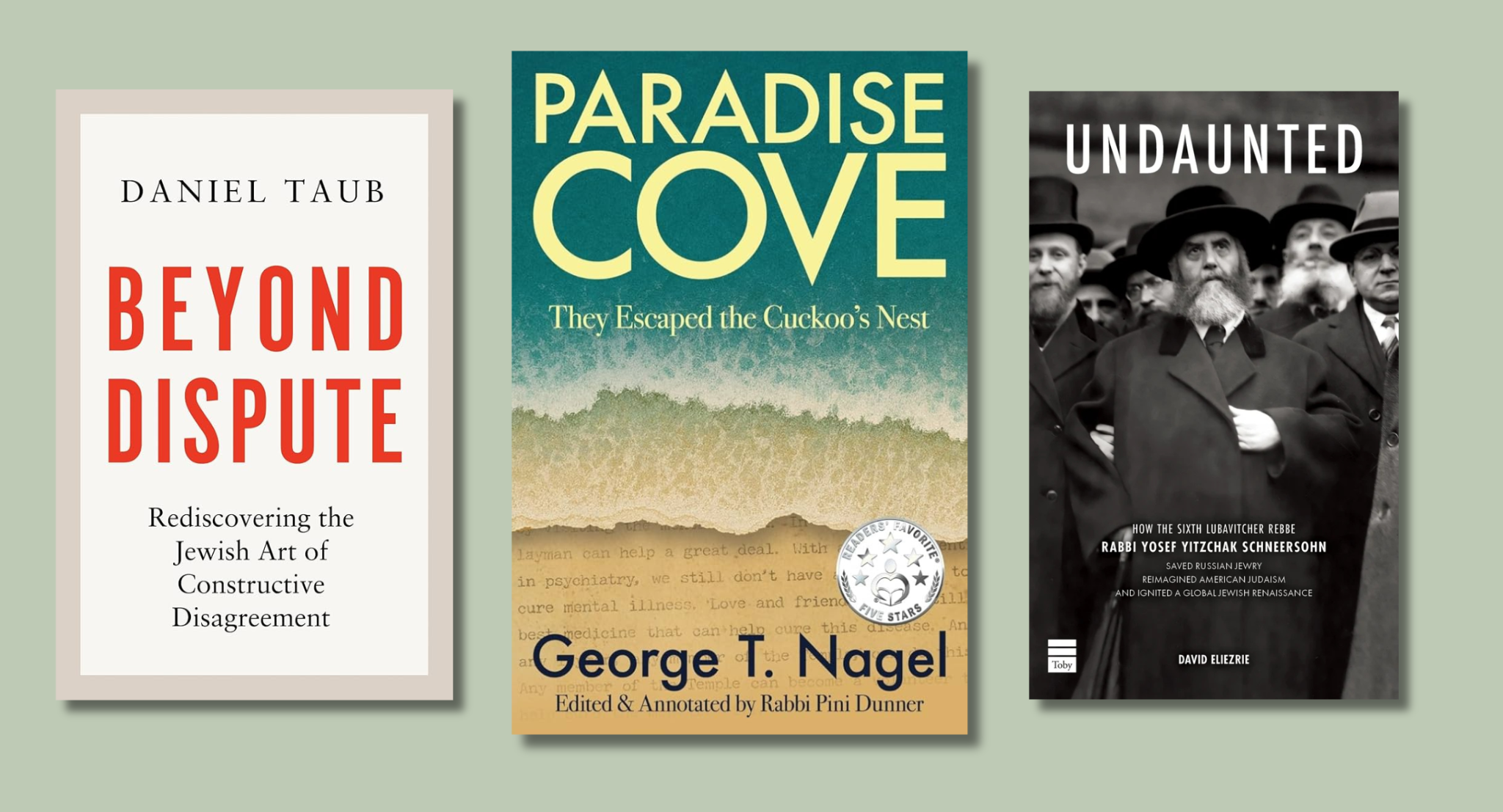

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

Rav Tzadok of Lublin on History and Halacha

Rav Tzadok held fascinating views on the history of rabbinic Judaism, but his writings are often cryptic and challenging to understand. Here’s…

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.