Rabbi Beryl Gershenfeld: What We Can Learn About Teshuva From Jewish Outreach

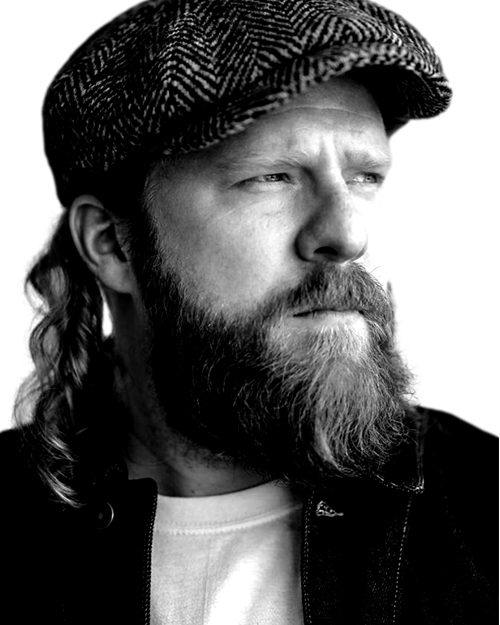

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, R. Beryl Gernshenfeld, one of the leaders of the Jewish outreach movement, joins us in talking about what we can learn about the process of transformation that occurs in Jewish outreach.

Summary

This series is sponsored by our friends, Daniel and Mira Stokar.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, Rabbi Beryl Gernshenfeld, one of the leaders of the Jewish outreach movement, joins us in talking about what we can learn about the process of transformation that occurs in Jewish outreach.

- What was Rabbi Gershenfeld’s path to outreach and teshuva?

- What can the Jewish world learn from Jewish outreach?

- How do we engage in meaningful growth?

Interview begins at 15:25

Rabbi Beryl Gershenfeld has been designing and teaching educational programming for post-college Jews since the early 1980s. Rabbi Gershenfeld serves as the dean of Machon Yaakov and Machon Shlomo, and is the founder of MEOR, which provides Jewish literacy and leadership programs on more than 20 college campuses across the United States.

References:

Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought by David Bashevkin

The Road Less Traveled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth by M. Scott Peck

Sefiras Haomer: The Link Between Tushuva And Torah by Yaakov Elman

Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Atomic Habits by James Clear

Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing by Pete Davis

Aspiration by Agnes Callard

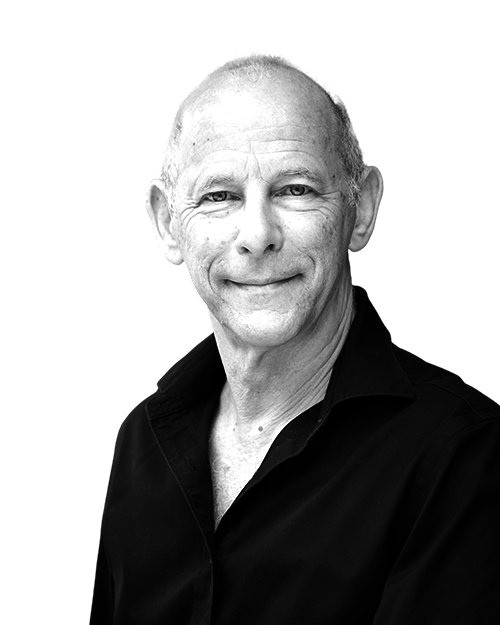

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty podcast, where each month we explore a different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring the topic of teshuvah. This podcast is sponsored by our dearest friends, Daniel and Mira Stokar. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18Forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and our weekly emails.

One of the best icebreakers I’ve ever heard, and Lord knows I hate icebreakers, I can’t stand them, especially at a Shabbos meal. But I one time sat at a Shabbos meal with my dearest friends, Ari and Atara Segal. I don’t know who started the icebreaker, but there was an icebreaker, and they went around the table asking everyone, “What is your favorite parsha? What’s your favorite parsha in the Torah? And I loved it, it was so informative and interesting, and I couldn’t come up with one answer so I said, “I have really three parshas which I love the most, it’s hard for me to select.”

Number one was probably Ki Tisa, which is the story of the golden calf, chet haegel, it’s just a magisterial parsha. Number two was Parshat Ve’etchanan, which we always read on Shabbos Nachamu, and it’s just this really amazing story about Moshe pleading with God to be let over and enter into Eretz Yisrael, enter into Israel. And God’s answer is ultimately “no,” and it’s just an incredible parsha. And the last parsha, which is really the easiest because it’s the shortest, is Parshat Nitzavim, just 40 pesukim long, 40 verses. And I’ve always loved Parshat Nitzavim, and the reason why I loved it and really the common denominator in all of the parshiot, all of these texts in the Torah that I love ever so much, is the common denominator of teshuvah itself.

And it is in the Parsha of Nitzavim that we actually confront, perhaps for the first time, a commandment, the notion that we are even commanded to do teshuvah. The way the Torah writes it is, “Ki hamitzvah hazos,” this commandment, “asher anochi metzavcha hayom,” that I’m commanding you today, “lo nifleisi mimcha,” it is not so outlandish or not so otherworldly for you, “v’lo rechoka hi,” it’s not so distant, “lo bashamayim” it is not in heaven, “lemor,” that someone could say, “mi yaale lanu,” I got to go all the way to heaven to get it back. Rather, the mitzvah of teshuvah, this commandment, this notion of teshuvah, concludes, “Ki karov eilecha hadavar meod,” it is exceedingly close to you.

And what I find so fascinating about this presentation is that we’re not even sure if it is talking about teshuvah. There are actually two, perhaps three conflicting readings about what exactly is this even talking about. It begins, “Ki hamitzvah hazos,” this commandment, this mitzvah. Doesn’t really say which mitzvah, we take it for granted. We talk about it as if it is the source of teshuvah, but we don’t really know that for a fact. It doesn’t say that explicitly. In fact, the word “teshuvah” doesn’t really appear in the Torah at all. We have a verb “lashuv,” to return. We don’t have this noun of teshuvah, something that I actually address in my book, “Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought,” to push a little product for a moment. This notion of some words, teshuvah, avera, there are a lot of words that do not appear in the Torah. The word for repentance, or loosely, poorly translated as repentance, and the word avera, poorly translated as sin or transgression, none of them appear in the Torah.

But the dispute that I find incredibly fascinating, is what exactly is this mitzvah even talking about. The Ramban on this very verse, and this is the 30th chapter in Sefer Devarim in Parashat Nitzavim, the 11th verse, the 11th pasuk. The Ramban writes that this verse is talking about teshuvah. It is God telling you that teshuvah is very close to you, but the Talmud in Eruvin in Bava Metzia seems to understand that the mitzvah over here is not talking about teshuvah. It is in fact talking about the mitzvah of Talmud Torah, of learning Torah, of studying Torah. And I’ve always found that dispute to be fascinating that they’re both looking at like, there’s this mitzvah that is incredibly close to you, it is something that is in your hands. And the question is which one is it? And some say it is teshuvah. And some say that it is Torah. My rebbe, mentor, professor, Dr. Yaakov Elman, who I’ve mentioned many, many times on this podcast, he went on to be an incredible professor of Talmud. He had a very, kind of humble beginning in the Jewish world. He did not begin as a professor lecturing in universities. He taught in Harvard, he’s published in every major publication. He really began as like a yeshiva student, and the first place that he used to publish, to my knowledge, the first place, was in the old Jewish Observer magazine, alav hashalom, of blessed memory. It no longer exists. My heart breaks every time that I say it. And there’s just a trove of amazing archives in the Jewish Observer. So there is one issue of the Jewish Observer, which is famous for multiple reasons. The primary reason it’s famous is not because this is the issue where Dr. Elman published an incredible article that I’m about to reference. It’s actually most famous because of a very heated polemic that I’m not going to tell you about on air.

You have to go to the Jewish Observer archives that exist online in Agudah and check out which polemic am I talking about. And Lord, knows — for those who ever read the Jewish Observer, which was the magazine of Agudat Yisroel — they oftentimes were wearing boxing gloves when they wrote an issue. It was intense, and this is one of the most intense polemical issues, but that’s not the article that interests me. In the April 1988 issue of the Jewish Observer, my rabbi — before he was a fancy professor, before he had a PhD in Talmud — wrote an article called, “The link between teshuvah and Torah,” where he essentially discusses how this connection between Torah and teshuvah is not at all happenstance.

The common denominator between Torah and teshuvah is the act of personal transformation, the ultimate creative act. To be engaged in Torah study is not just to read what rabbis are telling you, but to kind of transform and interpret and find yourself and your own story and your own narrative and your own ideas within the text of Torah, to be able to append your own experience and ideas into the larger canon of Torah.

And that obviously doesn’t just include the written Torah, but it includes the entire canon through all the generations, and find a way, and almost like append your letter through your own experience into the world of Torah. And it is that creative act that the ultimate creative act, the ultimate act of transformation, the ultimate act of creativity in Judaism is actually the act of teshuvah. It is the creative interpretation of self. If Torah is a creative reading, where you take yourself and you read it into the Torah, you find ways through your own logic, interpretation, and you find through the act of Talmud Torah, a place where you and your experiences can reside and be interpreted. The act of teshuvah is an act of interpretation and reinterpretation of self. It is a creative reading of your own life and your own experiences.

It’s fascinating to read because Dr. Elman recreated himself so many times. And when I read this, I’m used to reading his fancy academic articles. And when I read this, it takes back when he was writing to a… let’s call it straight, to a more yeshiva audience. The Jewish Observer was not Harvard Theological Review. It’s not JQR or some fancy academic journal. So he wrote with maybe it was a little bit more warmth. It doesn’t have that academic, sober writing style. And he wrote as follows: “Since teshuvah is a process of recreation, one who has been renewed by the experience of repentance can see Torah and mitzvah observance in a fresh invigorating light. This act of recreation, the act of reinterpreting your own life, which is the act of teshuvah, really begins and is intertwined in so many ways with what Talmud Torah, the experience of learning Torah is, which is a creative interpretive reading of the text itself.”

And that is why it is such an incredible privilege for me to speak today and introduce our guest Rav Beryl Gershenfeld. Rabbi Gershenfeld is somebody who had a formative role in my life, in showing me the creative reading of Torah and the depth of what Torah experiences, and dare I say the act of Talmud Torah, the act of immersing yourself in Torah as an act of teshuvah itself, as an act of self-recreation, self-interpretation, realigning, and reorienting your very own values.

I first met Rav Gershenfeld, I believe, when I was studying in my year in Israel, in Yeshivat Sha’alvim, he visited one Shabbos and he spoke a few times in Yeshivat Sha’alvim and I was frankly blown away. I never saw somebody with such a deliberate, careful reading of Torah text. And he was really one of the early people who helped me fall in love with what is known as Machshava, Jewish thought, creative readings of Agadata, the world of the Maharal, of Rav Zadok, the world that I still in many ways inhabit today, in so many ways he built the doorways.

I later on, and it was such a disaster, I arranged a chabura, a small group study, in his apartment. I had to nag him forever to do it. I understand why now: it was a group of students who were enamored with what he said over Shabbos. And we said: “We want to come over and learn with you.” And he’s busy. He runs two major yeshivas. He is a major figure in the Kiruv movement, the Jewish outreach movement in America today. He has an organization called Meor which I will talk about in a moment, but I just kept on bugging him and said: “We really want to come together.” And I still remember to this day, we came to his house to learn right before Lag Ba’omer and what was so fascinating, I still remember everything that he said, but I remember his reading was from a book that, maybe it’s got a little more controversial because of the life of the author, but it was a book called: “The Road Less Traveled.”

And he opened up from the very beginning. He told us initially, he said, you have to skip the last third because it’s extraordinarily Christian. But he began reading right from the beginning in that chabura. And this is from the beginning of “The Road Less Traveled” by M. Scott Peck. The author is not really a paradigm of values, but I have found the book incredibly meaningful. And the book begins with a chapter called “Problems and Pain.”

Writes as follows: “Life is difficult. Life is difficult. This is a great truth. One of the greatest truths. It is a great truth because once we really see this truth, we transcend it. Once we truly know that life is difficult, once we truly understand and accept it, then life is no longer difficult, because once it is accepted, the fact that life is difficult no longer matters. Most do not fully see this truth that life is difficult.”

“Instead they moan more or less incessantly, noisily, or subtly about the enormity of their problems, their burdens, and their difficulties, as if life were generally easy, as if life should be easy. Their voice, their belief, noisily or subtly that their difficulties represent a unique kind of affliction that should not be, and that has somehow been specially visited upon them, or else upon their families, their tribe, their class, their nation, their race, or even their species, and not upon others. I know about this moaning, because I have done my share of it. Life is a series of problems. Do we want to moan about them or solve them? Do we want to teach our children to solve them?” And he began with this and I just became so drawn in with the way that he weaves together these amazing teachings about the depths of Torah with contemporary ideas.

And he builds this edifice of Torah that really allows you to reorient your own sense of self and really become anchored in something timeless. It feels like an act of Talmud Torah that, as you are listening to him, as you are hearing the deliberateness and the discipline through which he teaches and carries himself, that you feel that the worlds of Torah and teshuvah in the same way that they appear, so to speak intertwined in that “ki hamitzvah hazos,” in that very early chapter and discussion in Parshat Nitzavim. You feel them being intertwined once again, when you hear Rav Gershenfeld teach Torah. I was lucky enough when he ran a camp, it was like a Jewish outreach camp, it was a really amazing experience. I made a lot of friendships that endured there for many years. When I was in the camp there Rav Gershenfeld and I became even closer.

I was like the gabbai. I ran the shul, and we learned together at night. We learned the Maharal together and we would take walks and we would speak and we didn’t stay in touch. To this day I’m not a 100% certain that when I reached out to him to appear on 18Forty, that he even remembered who I was. But I do know that there is a majesty of Torah that he is able to present that the Torah itself serves as an act of teshuvah. That the creative interpretive process, the transformative process of Torah is able to transform self and the transformation of self also transforms your relationship to Torah. They are so to speak intertwined in the same way that Dr. Elman discusses in that article in the Jewish Observer so many years ago. So when I was looking for someone to talk about teshuvah and to kind of kick off our very discussion in this series of teshuvah, I knew I wanted Rav Gershenfeld, and Lord knows it was not easy to get him to commit to an interview.

And it’s not his normal style of delivery. He is an educator of Torah to his core. He is not your typical podcast guest, but I was fairly persistent and he was incredibly gracious and patient throughout. And really trying to learn about what he does and how he presents the words of Torah to allow for so many, dare I say thousands, it must be thousands at this point, in his yeshiva, through his yeshivas known as Machon Shlomo, Machon Yaakov, in his campus movement for Jewish outreach, which is known as MEOR, which I believe in the interview, I incorrectly called Maimonides, because I get mixed up with all the Jewish organizations. It is called MEOR, and he really, I believe, is the single most important figure in Jewish outreach and so to speak the teshuvah movement, if you want to call it such, today. And he had an incredible impact on me and the way I relate to Torah and to teshuvah itself.

So it is my absolute pleasure and privilege to introduce our conversation with Rav Beryl Gershenfeld. It is my absolute pleasure. And I’ve been saying this for some time and really more than a pleasure. It is a privilege to be sitting with someone who has had an incredible impact on me, although we only spent one summer together and I’ve only had the privilege to read one of his articles in English, but I feel like I am one of the students who was never fully a student, but a student nonetheless. And that is why it is my absolute pleasure to introduce our guest today, Rabbi Gershenfeld.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Thank you. Pleasure to be here with you. And I consider you… You did also, because I know we shared the same vision, even though it was decades ago.

It’s really, really something for me, very excited to speak. We got to know each other many, many years ago in a summer program that was then known as Moodus. I think the name has changed. But we’re talking this month about teshuvah as we often do before the High Holidays. And I was wondering if we could begin before we talk about how you facilitate and engage in the teshuvah process specifically in the ba’al teshuvah movement. Tell us a little bit about your story of teshuvah.

Okay, let me be a little ornery and refocus the question, then we’ll get to my story. The question: “What’s the word teshuvah mean?” That’s the question that’s got to inspire and direct thoughts if we’re talking about teshuvah and we probably all know the first answer of what it’s not. The translation “repentance” is clearly not what the vision of Judaism is. That English translation comes from the word penitent, to be sad, regret and read to go back to sadness and regret again and again and again, that’s clearly not Rambam or the Maharal or Rav Kook’s idea of what teshuvah is. Teshuvah is to return. And the question now, what are you returning to? That becomes the answer that has myriad responses in Klal Yisrael. And that’s what makes teshuvah personal and powerful. And if I’m going to tell a story about myself, then it has to be: “What are you returning to?”

So famously I think we’ve got Rav Yerucham, the Alter of Kelm, teshuvah is returning to yourself and the depth of yourself. The Maharal, the Chovas Levavos, teshuvah is returning to relationship with HaKadosh Baruch Hu. Maharal, on a deeper level, it’s returning to a tzuras elokim, into a high form of what’s the best you that you could be. So if we’re going to tell the teshuvah story of Rav Beryl Gershenfeld, the teshuvah of how I returned to myself is my process that I grew up in a wonderful Jewish home in Philadelphia. My parents were both academics. My father was a doctor. My mother was a psychologist and I grew up in a world of ideas. My grandfather was a dean of a university and it was clear to me as a very young boy that I think most people think that the way you’re happy or good is just by being smart or making a lot of money.

And it was clear from the people around me that there were many very smart professors who were my parents’ friends, and they were experts in their field, but they weren’t good people. At a fairly early age, 11, 12, 13, this question concerned me and I felt that, gee, I’m supposed to be smart, I’m supposed to be good, but I don’t see how academics is going to make me smart or good. And this began a question of recognizing that, looking for ethics, looking for ideals, looking for values was the key question that had to be answered in life. I think obviously lots of credit has to go to my parents who, although they’re not what’s called religious, were very, very drivenly, moral, good people. And I felt that the only thing in life to be was to be good. The question was, how do you be good? And that question led me to looking at religion, which I thought was antiquated and remote and trying to come to grapple and grasp with that. Think probably I was 12 or 13.

I told my parents I wasn’t going to synagogue one Rosh Hashanah, that I wasn’t sure if there was a God or if there wasn’t a God, but I knew if there was a God, I wouldn’t be praying to them the way we were praying in our Temple. And this began a process of looking for ideals and values, morality, and truth. Trying to understand the big question of how do you craft a good life. And since I grew up in Philadelphia, I grew up in a suburb of Philadelphia, it began with there’s a reconstruction, a seminary that is near where I lived, began questions over there, went on and developed into a relationship with Conservative religious thinkers, Abraham Joshua Heschel, further began taking trips to Boston and Rav Soloveitchik. And I was exploring through my teens until this day Judaism, trying to figure out how does one become a good person?

Is there an absolute truth? Is there an absolute morality? And I want to preface it by the discussion [of] what teshuvah is, because the one lodestone, the one north star in my life was that I felt that there was — and this, I feel is a deeply Jewish idea, deep idea of Vilna Gaon — I had the tzelem elokim inside of myself. I felt that there was a divine image in me that had a moral message. And I knew that life is about purpose and life is about goodness and life is about finding the purpose of life. And that enabled me to navigate questions, streams, struggles, ideals that I was returning to myself. That my struggle for teshuva was to find a deeper me and to express the real me. And that’s the process of teshuva that I was on then and I’ve come on now. People usually like the story that I’d gotten to a point where I was keeping many mitzvahs, I had learned a lot in university. I was president of the Hillel on campus.

David Bashevkin:

Which university?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Trinity college in Hartford, Connecticut. And I was invited to a meeting with Golda Meir, of 20 students who were going to be student leaders, to talk to Golda Meir about what was the future of Judaism in America. Being a overly cynical and perhaps self-absorbed college senior, I told my parents, I had much too many things to do that were too important to waste a Sunday afternoon going to see Golda Meir with 20 people. And I had no clue myself what Judaism was going to look like. I had no vision of what would cause renewal for Judaism in America. Wanted to skip it. Mother and father in the classic Jewish ways. Dad said, You have to go, you’re going to meet movers and shakers there. Mom said, you have to go you’ll meet nice Jewish girls there. I caused my parents, I think, so much trouble and angst wearing a yarmulke and being shomer Shabbos and breaking certain of their visions of what my life was going to be like.

I said, okay, I’ll be a good boy, I want to go. But doing a very non-Gershenfeldian attitude. I would not speak, that I don’t have the audacity to speak in front of the prime minister of Israel about what the future is when I don’t know for myself and I’m still grappling and growing myself. A dangerous thing happens, Reb David. I’m not sure if it happens to you also, it’s a rare thing by you I’m sure too. I was quiet for three hours and I listened to everybody and I kind of walked out of that meeting and realized that the sad thing was that I knew more about Judaism than any of the other 20 students in that room.

And I was pretty sure I knew more about Judaism and Torah than Golda Meir did also. And that created a vision in my mind that it was not just sufficient to guard Torah and mitzvahs, but I had to become a extremely well-versed Jew and accept responsibility that if you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem. And it was a difficult situation for I was planning to go to law school and I decided not to go and that I had to go to yeshiva for, I decided at that time, at least for two years, turns out it’s about 40 years, and try and learn, so I could lead a better Jewish life and a more inspiring Jewish life. A Jewish life more based on the depths of myself and the depths of the text. That’s a little bit of where the teshuvah story goes.

David Bashevkin:

And which yeshiva did you originally enroll in?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

So again, [I] went to Israel before the regular, I think, teshuva movement became institutionalized. I went to a Yeshiva called Shema Yisrael. It was the original precursor of Ohr Sameach, Aish HaTorah and Machon Shlomo. It was in a building, in the Novardok yeshiva at that time in Yerushalayim. The building was not complete. I slept in a sleeping bag on the ground. I think I was the 14th student in the yeshiva.

David Bashevkin:

Wow.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Rav Noach Weinberg, Rav Nota Schiller, Rav Yaakov Rosenberg, Rav Aharon Feldman were all there, I had a feisty excellent beginning. And that’s where I was for two years.

David Bashevkin:

So I actually want to shift a little bit to that institutional world of Kiruv that you mentioned. You run two yeshivas and you’re involved in so much of the movement, Machon Shlomo and Machon Yaakov, which are yeshivas that are specifically catering for people who are beginning their journey of in-depth Jewish learning. You’re also involved in the Maimonides on campus program, as well as a lot of the summer retreats. And I’m curious, you made reference to it, the feistiness. I’m always scared to use the word of strategies, approaches, but there are different ways that different Jewish institutions think and conceptualize the world of outreach. Is there a specific approach that you take when it comes to engaging ba’alei teshuvah, people who are returning back to Yiddishkeit and more in-depth learning?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Definitely. And probably the way all of us do it is we do it by what resonates with our inner selves and look around to see if there’ll be a party of people that resonate the same way and join us. We don’t have the only approach to teshuva, but we have one approach that I saw that I had to craft kind of my own journey at the time. And when I look around that reality is still the one that faces us. So I think the idea that there’d be three foundations that when I try to teach Torah, discuss Torah ,and spread Torah… the first one is that we call our organization on college campus Meor. We call it Meor clearly on the midrash, second midrash in Eicha Rabba, that “Meor shebatorah machziro l’mutav,” that the light of Torah will return people to good, right?

Yirmiyahu says: “Oti azvu, et torati lo shamaru,” the prophet Jeremiah says: “They’ve left me and they’ve even left my Torah.” With that comment, Rav Chiya bar Abba says: “You see that if they left God, but they kept the Torah. The beauty of the light and the depths of Torah would bring them back to good.” That’s I think our clarion call in our mission statement that if people leave Torah, there’s a way back in by learning Torah, not just asking them to keep Shabbos and think about God. Not just asking them to put on tefillin, but there’s a process of the mitzvah that’s most important to Klal Yisrael is learning Torah. And without footnotes here, meor shebatorah means not just learning Torah, but learning it an illuminating Torah, an invigorating Torah, the light of Torah. The way of engaging in a sophisticated manner, that if we’re learning at university at a high, sophisticated, relevant manner, we have to provide Torah at the same high, sophisticated, relevant, deep, engaging manner.

And that Meor, that light of Torah, will bring Jews back. Second understanding of the text, it doesn’t say: “Bring them back to Torah,” it says: “Bring them back to good.” “Hameor shebatorah machziro lamutav.” The vision we have is not just a vision of doing mitzvahs or being what’s called frum, being religious. The mitzvah is making a person a holistic human being, an adam hashalem, we always call it in the language of the Ramchal, language of Rav Yisrael Salanter. And that’s clear[ly] the second aspect of Meor… besides just the belief that wisdom is the way to help Klal Yisrael reconnect with our legacy.

The second aspect is that the goal for that Torah is not just being religious. It’s being an adam hashalem, it’s self-actualization, and it’s bringing us to an ethically high developed level in which the way we work, and the way we raise children, and the way we relate to our spouses, the way we relate to community issues, and the way we relate toHaKadosh Baruch Hu and the way we relate to mitzvahs are all expression of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, the goal and the vision is that we are holistic.

And the reason Torah is important is it’s not just connecting to God. It’s connecting to yourself and actualizing yourself. That’s the second aspect that I think Rav Yisrael Salanter and Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto express that very much the language of our Torah is the Torah is for you to make you a fuller, more complete person. It’s mutav, it doesn’t say to make you frum, it says: “To make you good,” a holistic, complete developed person. And then perhaps the third emphasis we have, I think, in all the programs we try and teach, maybe this is more of a awakening inspiration for the religious world is… I’m always inspired by the Midrash in Tanna Dvei Eliyahu Rabba, perek dalet. The Midrash asks a profound question, which most people know the answers of recent authorities, the achronim, but the Tanna Dvei Eliyahu Rabba, the Midrashanswers profoundly. Why was it that when God gave the Torah over the first time in the first 10 Commandments, Moses not come down with an illuminated face, he did not come down with meor panim?

Second language of meor panim is not just describing that Torah illuminates, but the goal of human life is to have an illuminated passionate face. Why wasn’t Moshe Rabbeinu’s face meor panim, the midrash asks, when the high level Torah was given of the first reception of Torah. When he came down the second time in Exodus 34, there he came down with an illuminated face. There he had the passion, there he was inspired. So the midrash basically says that the first time Moses thought that the key to life was just to learn Torah. After the Jews sinned, and he saw that it wasn’t enough just to learn Torah, he had to also love Jews. He had to be a leader. And when he saw that he had to lead the Jews back in teshuva, he had to lead them back and repent, and lead them back to the right path, then HaKadosh Baruch Hu said: “Now, if you love Torah and you love people, up, now you get meor panim, then you need an illuminated passionate face. So third aspect, I think, of our big vision at Meor is that the Torah you learn is part of social change and it’s to make you a leader and to make you to be part of the response to the problems and responsible to help the community and the world around you grow and develop. You can’t just love Torah, you have to also love people around you and help those people become more complete like you are also. So I’d say that when we started Meor in 2005 or whatever, the last thing in the world I wanted to do was start a educational project on college campuses. I think naturally my parents are professors, I think I’m naturally a professor called a rosh yeshiva, but I saw that the portals to Judaism on campus were not expressing these ideals that I think are crucial.

Either it’s just be Jewish, be Israeli, just experience Shabbos and you’ll naturally feel it. That didn’t work for me, and therefore I felt that I was responsible to try and express a beautiful, beautiful tradition of Judaism that I felt wasn’t being expressed in America. And it’s based on these three ideas. That Torah has to be profound and deep, based on the idea that Torah is about actualizing your own potential, bringing mikoach lepoel as the Arizal and the Maharal say many times, self-actualization. I’d use word self-actualization. So many people think, oh, you’re into Carl Rogers. I said: “No, 500 years before Carl Rogers ever existed, the foundational understanding of why Adam is called Adam, why man is called man and why tzitzis are called tzitzis is because we understood the essence to life is that we’ve got a divine image inside of ourselves. And our mission is to actualize that, we have to have aspiration, and that will inspire us to achieve what we have to do as Jews.

David Bashevkin:

I’m curious, you talk about introducing this type of Torah. I’ve studied Torah with you. You were kind enough. We only got to get together a few times, I don’t know if you remember this. We used to learn after maariv We would learn the Maharal’s commentary on the aggadahs in the Gemara. I’m curious for you, is there a starting point, meaning somebody comes to you, how do you introduce this Torah? Is there a curriculum? Is there a specific entry point? Like this is where you should start with the laws of monetary law in Bava Kamma. Start with the beginning of the first mishnah in Berakhot, start with the beginning of Chumash. Is there a starting point for how to introduce or how you go about introducing Torah to people who have otherwise not had this experience prior?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Always two answers. First answer is no. We have a Gemara, [the] Gemara famously says in Avoda Zara 17, “Ein adam lomed Torah ela mimakom shelibo chafetz,” a person can’t learn Torah except where his heart desires. So the beginning of a good rabbi is I have to see what interests you. If what interests you is the depths of playing tennis, then I have to try and show you how your desire for tennis is an expression of your divine image and an expression of your spiritual goals. And to try and show you that in a deeper way that you want to enter into a deeper world. If your interest is in how to make relationships, then we have to talk about relationships and try and show you that in a Torah light. So the beginning in this world is I usually, our tagline at Meor is “Inspiring, educating and empowering.” The first vision has got to be to inspire.

Let’s touch something. Once you’re inspired and you see, ooh, it’s worthwhile learning. There’s something deeper and more relevant over there that can help me achieve my goals in life. Now you can educate me. Now I’m ready to learn things that you’d want to teach me that I don’t want to learn. Then of course the ideas at the end, after we’ve inspired and educated. Now the job is on power. You’ve got power, go out and try and make a better world. There’s something else for you to do out there.

Now, of course, it’s not all the time that you can focus on one person. So when we have to speak to a group of people, two ways usually we’ll try and engage them. One is we’ll talk about what the essence of being human is. If the goal is to be an adam hashalem, let’s sit down and take what a definition of human being is and what the etymology of the word Adam is in Hebrew and what the etymology of the word mitzvah is. And let’s figure out what the process, what does Torah want from you? And that’s going to engage a person with a bigger view of what’s going on. Second, we’ll take classic texts that people think are boring and irrelevant, and let’s look at what’s the first myths in the Torah. And why is it crafted the way it is? What does Bereishis mean? What does the 10 commandments mean? What does Shema mean? So we’ll take texts that people think are irrelevant and dogmatic, try to show them as being bright and empowering and sophisticated and inspiring.

David Bashevkin:

I’m certainly not answering for you, but as I asked the question, I actually reminded when we spent that summer together. So I don’t know if you knew this, but I used to go back and I used to take notes anytime that I would hear you speak. So I have a pretty good reservoir of stories. And one of the stories that I remembered you saying, which is not the answer that you gave now, but it’s just such a moving story. And I think it took place on the High Holidays, I believe, on Yom Kippur, was a story of Rabbi Dessler in Ponevezh.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

This was one of God’s gifts to me in my life, I think. I was learning in the Mir yeshiva, kind of minding my own business I thought. And it turned out that someone came up and said, You like Reb Dessler, Rav Gershenfeld likes ethics, and deep ideas. One of Reb Dessler’s students is going to give… It’s the 25th yahrzeit, the 25th anniversary of the death of Reb Dessler, who was the great Mussar leader in the approach of Kelm who became the leader… mashgiach, the spiritual advisor of Gateshead and then Ponevezh. And it was 25th yahrzeit so I went to Rav Moshe Shapiro’s house who later I was zoche to learn much, much Torah from. And he explained that the most powerful experience in his life, he was trying to think what he got from Reb Dessler. And what he remembered was that was Rosh Hashanah and at Ponevezh in those days, the electric generators would get overheated if they went 48 hours straight. So it was a period of half an hour at the end of the first day of Rosh Hashanah that the generators would go off so they could cool down.

And the bochurim it was minhag avoseinu b’yadeihem, it was their tradition to go out on the veranda and talk about unimportant things on Yom Kippur. Rav Dessler was a new mashgiach at Ponevezh, this did not find favor in his eyes, Rosh Hashanah, to be not thinking about important ideas. And his response was, he sat down in front of the Beit Midrash, and he started saying over in the class of Rav Yisroel Salanter [an] idea that we have to penetrate the depth of a statement of Torah like we’re talking about… probe it’s profound depths, and to internalize the Torah, bring it into us and have it seep through every fiber of our being.

And he starts saying over a ma’amar Chazel and singing it in the classic Mussar style. And after he’d sung it 10 or 11 times, the wits on the veranda at Ponevezh were making their comments. “Clearly the mashgiach’s too old, he’s forgetting his learning, he’s saying things over again.” By the time he said it, 20 times Rav Shapiro said he was a young boy. He was back in the Beit Midrash, absorbing Rav Dessler’s relating to a statement of the rabbis. By the time he’d said it for the 50th time, there was nobody out on the veranda and everybody was in the Beit Midrash, listening to a person’s learn and live and learn and live a statement of the rabbis’ Talmudic discourse and just for himself. By the time it got to 80 times everyone knew that this was to be a moment that changed their lives.

When they got to the 99th time, he said, that everybody was ready. This was the Eliyahu HaNavi on Har HaCarmel experience. “Hashem hu Elokim.” God is God. It was clear to them, 101 times. And then they said Barchu and they went on and Rav Shapiro shared with me — which affected me profoundly, glad to see that we shared it, it affected you, Reb David profoundly — that he saw how deep a ma’amar Chazal is, how deep a statement of the rabbis is and how difficult it is for us to internalize and work with it. And that we can’t just read a statement of the rabbis and think we understand it, but to live a deep, full, inspired, engaged life is to be willing to work at something 101 times, and to recognize the depth and the beauty of the wisdom of the rabbis, and try and share that with people around themselves. And that, yes, that was the first statement I heard from Rav Moshe Shapiro. It changed my life. It clearly changed Rav Moshe’s life. And it’s the ideal that we’ve tried to live up to since hearing that statement.

David Bashevkin:

The part of the story that actually made the biggest impact on me was the afterword. Where you tell this amazing story, and I remember thinking it as you were telling the story, and I said, “I got to know which passage was this. Which part of Gemara, what page, what number?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

So of course this is what happened. So after the statement, one of the students listening asked Rav Shapiro, “What was the statement in Chazal that was being quoted?” and Rav Shapiro, who had a very sharp sense of the depth and precision of learning Torah completely obliterated the boy for asking this question and said: ” What am I, a journalist? If I wanted to tell you what ma’amar Chazal it was, I could have told you, but what’s important to me is that you can do it for every ma’amar Chazal. You can’t ask that question. You shouldn’t ask that question.” As I assume I shared with you later on, I would never ask Rav Moshe afterwards, but I asked Jonathan Rosenblum when Jonathan Rosenblum wrote his Rav Dessler biography to please, I gave him a couple of people to talk to, and please find out what the ma’amar Chazal was. And we found out what the ma’amar Chazal was, and we can share it, but that’s more of an in-depth thing but-

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, I remember after I believe it was Shabbos 31-32

Beryl Gershenfeld:

–32. Correct.

David Bashevkin:

… Yes. It captured me hearing the story.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

And then I had the audacity myself, that somehow didn’t shake me. And I had the audacity, afterwards, to ask Rav Moshe. I said: “Reb Moshe, what’s the big deal, what… Of course I’ve read “Ohr Yisrael,” the sefer of Rabbi Yisroel Salanter where he says, this is the way to grow great using by the Rabbi Akiva the water dropping in the stone metaphor. Of course, this is what you do. And then I got lightning and thunder from Rav Moshe that, yes, but you don’t understand that the Olam is a golem. The world is an unformed clay. What they do, they do because they don’t have a rabbi. What you do, you have to do, because you do have a rabbi and you have to not just make this a story, but you have to live with this. And of course, the after stories, the lightning and thunder afterwards had their big impact on me, also.

David Bashevkin:

The after story is always where the magic happens. I was wondering if we could kind of continue in this theme, even in your own story and the way that you described the teshuva process, there’s something very beautiful about the ohr, the light of Torah, so to speak, being machzir, returning somebody to good. And I think in a lot of people’s process of teshuvah, whenever it begins or takes place, whenever they want to come up with that self-actualization. I always think that there are two parts to that story.

There’s one part where it’s like, you feel this misalignment in your life, something, this goodness is not there and you come toward something — t’s a rabbi, it’s a community, it’s an idea. And you start moving toward something. And then there’s this second chapter, which is the rest of your life. And that second chapter is the rest of your life inside of a community, going to a shul, paying your dues, finding out that you pay tuition and the cost of life and all the other difficulties and things that are maybe, I never want to cast aspersion on the Jewish community, but we could speak plainly.

You get exposed to a lot of things that are not good. And sometimes things that are not good coming from a world that ostensibly you would think embrace Torah. So how do you prepare? I had one friend who could always spot somebody who was part of the German Yekke community. He just knew from the way their shirt was tucked, in the way they were walking. I have a skill, I could spot graduates of Machon Shlomo and Machon Yaakov. I can just spot it. There’s a decency that they have.

And I’m wondering how you’re able to foster that long-term religious stamina, not to be bombarded by the cynicism. They came to become good. So now they’re going out to communities. They’re not in this comforting insular world of yeshiva, of Torah learning with a Rabbi, but now they’re out in the world. How do you avoid the erosion of that original commitment through the natural cynicism that takes place over the course of your life?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Great question, a great struggle. I’m glad that you’ve seen some people succeed in this struggle and this growth. I think the way to do it is to be real with the students when you’re learning Torah, to be real with the students and the student to become aware himself, how difficult it is to live a good life, and how difficult it is to change. I always tell people the most dangerous person to be around is a person who’s in the third to six months of his teshuvah. He’s been able to read all of “Mesilas Yesharim” and he can’t figure out why anybody else is not living at the level of chassidus, of saintliness, of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto and he’s dangerous, because he thinks it’s easy.

Once you’ve got to the sixth or seventh month, and you’re trying to change yourself and you realize you’re not a tzaddik, and that just like, it’s easy to talk about tennis and complain about tennis greats, until you start practicing, trying to hit the ball over. If you’re in the game yourself, and you’re real, we understand it’s gritty. It’s hard work and we’re in a constant process of growing. So just like we’re in a constant process of growing, and sometimes we fail, we sometimes succeed.

We understand that the world outside is in that constant process of growing and failing and striving and developing. And I hope that’s the part of the reality that we have to have. We talk all the time about that a student has to have an ideal and then he has to be real. And he has to have the process to connect the reality with the ideal. And that process is going to keep him moving and developing. And by not letting people just live in a bubble and by making it very clear that the end goal is not just to learn Torah, but just be an adam hashelam. An adam is a physical… Being a human being is physical, is inertial, is centrally driven. It makes a person realize, oh, I understand why it’s difficult for many people, probably also we’ve learned with most of the first year students “Mesilas Yesharim.” His introduction, his hakdama, is so clear about how many people don’t understand what the idea of chassidus is. What the idea of true Jewish living is. It’s almost expected, and maybe we go back to that story that Rav Moshe told me that you have to understand the Olam is a golem. The world is an unformed clay, what they do cause they don’t have a rabbi. What you do, you do because you do have a rabbi. And I hope that talmidim, students, understand that, and we’re all in the process of growing.

David Bashevkin:

And what happened, thank God you’ve been blessed with so, so many students and your time is so limited. I certainly know that firsthand and somebody reaches out to you and they say: “Rabbi it’s not working out. The sacrifice that I made, the reinvention of my life. It’s not working out.” How do you look towards a student and guide them, when you see that it’s already starting to crack five, 10 years later? They’re not holding it together. They feel like they bit off more than they can chew. They sacrificed more than they can bear.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Great question. Every engagement of course, depends on who the student is and what his potential is. The answers are usually clearly obvious. The answer is when a person comes and says: “I’ve bit off more than I can chew. My failures are overcoming me.” And the answer is: Okay, you have a new point of free will. Now let’s sit down and we just want to make small change. No one ever makes big change. You don’t go from doing 30 pushups to doing 50 pushups in a night. We’re just going to work to try and get from 30 pushups to 31 pushups and then 32 pushups. And the mission is always to, I think, try and have a person bite off something they can chew. Exactly, the way you made the question, which is literally calibrate…

We don’t know who tzaddikim are. We don’t know who chassidim are. We don’t know who kedoshim are. But you’ve had tests in life… Usually it’s a child who is extremely… has health issues. Usually it’s a financial catastrophe. Usually it’s a difficult marriage. And we say, okay, how do you deal with a bad marriage as an adam hashalem, as a human being. And that’s the test. That’s the vision we’re trying to go on right now. So I’d usually suggest that maybe the three things we do is, one is okay, there’s an issue of facing you right now. How, as an adam hashalem, how as a moral being does Torah expect you to deal with that situation? Let’s not worry about kriyat shema right now. Let’s worry about how can you be a better father to a sick child? How can you be a better husband to a wife you’re divorcing? How can you be whatever it is, let’s make Judaism real and see that right now, you can perform in a way that’s idealistic and makes you feel good.

Second is to put a schedule in of how you’re going to grow. We can’t grow in everything. Let’s figure out some area to grow, make it 15 minutes a day, and you’re going to feel so great about yourself after growing six months, if you focus and continue growing. That’ll be great. And the third ideal is okay, probably time for a cheshbon hanefesh, for a spiritual accounting. Let’s sit and figure out, why did you enter into a spiritual journey? How is the spiritual journey going to go? Probably a little bit of empathy and talk about other people that had difficult times in their spiritual journey. And let’s re-remember and rechart the course, find the north star and try and move forward. I think that’s usually what we try and work on.

David Bashevkin:

We’ve been talking almost euphemistically about teshuvah. Part of the question that’s always surfaced when people talk about the ba’al teshuvah movement is the question of denominational affiliation. They’re trying to make you Orthodox. My father grew up in North Adams, Massachusetts, and he became more observant, more Orthodox, in his teenage years. And my bubby was petrified. And she later came around and embraced all this change and loved it. But when she first saw him wearing a yarmulke in the house, she thought that he was being captured. I’m curious what role becoming Orthodox, so to speak, plays in Kiruv, meaning, what is the goal? And have you ever had a student who is still a student, but you knew, or you saw this person was never going to be able to integrate into the contemporary Orthodox community.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Clearly a question that touches the depth of every educator and every leader. And I tell “hameor shebo machziro lemutav,” the light that’s in the Torah returns people to good. I want people to be on a journey to goodness and to wholeness and to being adam hashalem. And my mission with every person I meet, every person I meet, every Jew I meet is to help them move along their path to development, to maturity, to self-expression, self-actualization as much as we can. So the story gets told over, the last words of the Alter of Slobodka, one of the people that I tried to connect to his vision and his ideals. So the Alter of Slobodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, died in about 1927. He was leaving his great yeshiva, one of the greatest yeshivas to come to make aliya, to come to Israel in 1923. And there’s this classic image that many different students define of Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel.

The Saba M’Slobodka gave the last speech in Slobodka as a vision of what everyone should aspire for as he’s leaving, and they would never see the students again in Slobodka. And he talked about the greatness of man. The speech so inspired the students that they followed him to the train station, and they kept asking questions about the speech, the lecture, as the Alter got onto the train. He got onto the train and the conversation continued and they were talking through the windows. The concept of greatness, of self-actualization, of gadlus ha’adam was so empowering, the train started leaving and the students were running next to the train to hear the Alter’s every new response to their questions.

They’re running to the train. Finally, a non-Jewish Polish conductor stopped everybody and said, you can’t go any further. And the Alter kept speaking over them as they asked questions and the Alter’s last words leaving Slobodka were: “I want everyone to be great. Even that station master. Even though he doesn’t want to become great.” Those are the final echoes of Slobodka. And that’s what I think our mission as Jewish educators is to make everybody –man, woman, child, Jew, non-Jew — recognize they’re made b’zelem elokim, recognize they’re made in God’s image and recognize they have a mission to make the world better and brighter.

And that’s we’re trying to go for and express. And therefore an educator sits down… I can’t walk up to you and say, I want you to do 60 pushups if you’re doing 30. The mission is let’s get to 31, 32, let’s get to 33, 34. Recently we had a student, I think we have to change details just for public consumption-

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

… a student from one of the best law schools in the world. And he wanted to come to Machon Shlomo and I told him that he couldn’t come. And he told me I’ve never been rejected anywhere in my life from a school. And I said: “Well, sorry, you’re an alcoholic, and you first have to grapple with your derech eretz kadma l’Torah, with your human being part of yourself before you start moving on to the Judaism part of yourself. Because we understand that life has to grow organically, we can’t just sit down and put tefillin on people and think that’s what we’re working for.

And people often ask me… I was asked by a director of a Jewish organization: “Rabbi, I can’t work with you, you have an agenda.” I said: “That’s right, everybody has an agenda. Either for profit institution or you’re a nonprofit, if you’re nonprofit, then you have an agenda to make the world better in some way. I have an agenda. My agenda’s clear. My agenda is to make everybody a more actualized human being and a more actualized Jew.

And I’m going to do that wherever we come along. If I see an Orthodox Jew and he’s keeping 613 mitzvahs, but he’s not happy with the 613 mitzvahs. If I see a person keeping the Torah and mitzvahs, and he’s not a loving, caring father, that frumkeit is not what we’re looking for. There’s steps he has to go to self-actualize, become an adam hashalem, a complete human being.

So I tell the wonderful, wonderful, devoted Jewish educators on Meor campuses that the mission is help everybody become a better person, a better Jew. And that’s what the process is going to be. Wherever we meet the people on that journey, that’s what we’re looking for. If someone meets me and meets a Meor educator and doesn’t feel like a better person, doesn’t recognize he has more potential, doesn’t recognize that Torah has more insight and inspiration for him, then we failed. But if the person’s not keeping Shabbos, that’s not a failure. The failure is a failure not to inspire, to educate, to reveal, to awaken ideas inside a person. And that’s what the journey is. And we all keep growing.

David Bashevkin:

You’ve already kind of touched upon this, but I’m curious, particularly in the Orthodox community, there’s always sometimes the idiosyncrasies that people who were raised within the Yeshiva world, especially now where the culture is so deep, it’s so sticky. It feels thicker than it ever has to grow up in the world, in the Orthodox world.

And they are idiosyncrasies of somebody who didn’t grow up in that world, who’s very kind and very decent and very wonderful, but let’s say a ba’al teshuvah who’s coming and integrating within that community, there are always idiosyncrasies, little ways that they can feel needled or pressured. I’m curious to reverse it and to think for a moment that when you visit, you’re on a trip now in the United States, what do you wish when you look at Orthodox institutions, the way we’re speaking within Orthodox spaces, what do you wish that you saw a little bit more, that you do see within the world that caters to ba’alei teshuvah, to people who are coming to be integrated within the Orthodox world.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

You’ve got me, Reb David, in something I don’t usually like to do. I usually look at my own responsibilities and try and move it forward. But I would think that the mission of Torah education in the world should be more personal. The concept that there should be a rabbi and a student, and there should be a personal relationship between the two of them. The idea of having large yeshivas without a personal connection with the rabbi, I think is difficult for people to grow, and we lose many people because of that.

Second of all, I wish that Torah education would be more relevant. Understand that a third of the people can grab onto the Brisker ideals of learning but many others need ethics, the Mussar aspects, need ta’amei hamitzvot, understanding why we’re doing mitzvahs, how we’re doing mitzvahs.

What’s the vision and what’s going on. As I learned with you seeing Hakadosh Baruch Hu, obviously the hashgacha was Rav Ashi and Rav Pappa put aggadatas and halachas together in Shas, and we’re supposed to have a broad, deep perspective of Torah from the aggadahs not just to skip over them and to learn them. And that recognition of the fact that the ultimate goal of a Jew is not just to learn Torah, but to melamed Torah l’amo Yisrael, that we’re trying to train people who are going to be leaders and teachers, not just absorbers of information. So those would be the concepts I’d want to share.

David Bashevkin:

So speaking of the information, I’m curious, in what ways. There’s so much more available online right now, and the internet has absolutely opened up access to Jewish learning. Also a lot of pushback, a lot more exposure to academic ideas. There are Facebook groups and all these places, and you could Google anything that you hear and find the point and the counterpoint of this and that. Have you at all seen or felt the influence or has anything changed in your approach based on what you’ve seen, the accessibility that the internet has provided for Jewish learning, both in good positive ways and in perhaps negative ways?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

I’m a traditionalist. I can find the ways that I think create friction and that we have to learn to overcome. The good parts I can obviously talk about also. It enables to get a mission out, but in my own personal journey, I think it’s the journey of the mesorah that we have from, Rav Moshe Shapiro, Rav Aharon Feldman, Rav Dessler, Rabbi Salanter.

This development of being able to find every inch you want and 13 answers and different approaches and different shitas. It’s not what inspired me to go into Judaism, It’s not what inspired me to be a Jewish educator. One of the reasons I don’t like to do podcasts and only doing out of my love for you and for the congregation, the tzibbur that you’re serving, is I don’t like what I consider a superficial aspect of, okay, there’s 11 answers to the question. Now we’ve researched it.

My vision much more is that we should find one answer. Probe it deeply. Recognize we’re listening to God speaking. Rav Moshe Shapiro told me that when we started Machon Shlomo, I asked him what foundation we should build it on? And he said: “The foundation should be that “lo bashamayim hi,” Torah is not “sham.” Torah’s not there. Torah’s right here in front of you. Every verse, every idea can be a ma’amad Har Sinai moment. It can be a moment with lightning and thunder. Before God gave the Torah there was lightning and thunder. Why did God give lightning and thunder before the …? He’s the world’s greatest educator? What do we need lightning and thunder for? The Maharal explains we need lightning and thunder to tell us there’s something big and powerful going on over here. So to me, the greatness of teaching Torah is trying to make that every word, every line is a ma’amad Har Sinai moment, is a revelation of the depth of the world and the depth of Torah.

That’s my idea of “meor shebatorah.” There’s a light, there’s illumination, there’s a power that’s going on. It’s interesting, I found that they translated Philo in English recently, so I could look at it, and Philo says: “You haven’t finished learning the verse”, right, from the 100 CE and Alexandria, “until you see God hanging in that verse.” And that’s what I think the beauty of yeshiva is, yeshiva is a place where we learn deeply about ourselves and deeply about life and deeply about Torah. And that’s what Meor tries to do to get that light. And that light is what we talk about every day in the blessing of Sim Shalom, right? “Barchenu avinu kulanu k’echad b’or panecha,” in the illumination of your face. Because that illumination, that light gives us Toras Chayim, gives the Torah that’s alive. I don’t want to just learn Torah. There’s got to be a Toras Chayim that’s got to be invigorating and deep.

There’s got to be something we’re going for. So the question over the last two years, all the parents ask, why does my child have to go to yeshiva? Let’s just do it on zoom. And really thank the students. Many students have the best two years they’ve ever had in their lives in Machon Shlomo, Machon Yaakov, because they realize that there has to be a culture of thinking deeply and learning deeply, not just going for a rapid 280 characters, we can go back and forth now. There’s something deeper, profounder… And we’re trying to listen to something… and trying to find the or panim. We’re trying to find the light that’s inside a deep [inaudible] that’s so appropriate for God to have said, for HaKadosh Baruch Hu to have said. Yeshiva is a place that we’re trying to make a culture of depth, a culture of seriousness, and there’s got to be lightning and thunder that comes before it.

There’s no lightning and thunder that comes before Twitter. There’s no lightning and thunder that comes before internet. So of course this discussion is interesting and good, and it brings people in and we need all the different pathways to Torah. But personally, this idea that you don’t need a culture, you don’t need a relationship with a rabbi, you don’t have to need a relationship to think deeper to yourself, that you don’t need a quiet space to learn the Torah, that we can do it in a noisy room with Twitter back and forth, or with emails back and forth. That’s an anathema to getting into a deeper place of who you are. And I think that’s one of the things when Torah stands proudly and the person experiences in-depth Torah learning, he goes, ooh, this is completely different. Yeah. I’ll still be enticed by the easy, light, cute, sweet Torah.

But when they’ve tasted the depths of standing at Mount Sinai, a Toras Chayim, a living Torah experience, I think that explains to us why we need a culture of a Beis Midrash, and a culture of a shul. So many people the last two years of coronavirus, people didn’t go to synagogues, they didn’t go to Beis Midrashes. And many people have forgotten how it is that a culture of a Beis Midrash creates a Beis Midrash, a place where you doresh, you look deeper than the normal eye looks at. Twitter at two in the morning is usually not exactly the place you’re going to find depth and meaning.

David Bashevkin:

Except of course my account. He didn’t say that explicitly, but it was implicit. It was implicit. You mentioned a Torah idea from Rav Moshe Shapiro, it’s one that I literally quoted and framed our entire last series on teshuvah. I heard it from you. I wasn’t sure if I heard it from you, but when you said it just now I knew, yes, this is another part of that reservoir of ideas that I wrote down of “lo bashamayim hi,” “shamayim” being… “sham” meaning they were there and it was always such a profound idea. And were always struck me, and I was wondering, I’ve never asked this question, it’s always bothered me.

Rav Moshe Shapiro, who I don’t know all of our listeners are familiar with, was this towering traditionally educated, learned in Ponevezh, traditional yeshivas. There was a special affinity he had with the world of ba’alei teshuvah, people who did not grow up with a typical yeshiva education. And I always wondered he could have taught Torah at the highest level to people who were raised this way, and he did teach Torah on those levels, but there always seemed to me to be a special affinity he had to the world of ba’alei teshuvah. I’m wondering if you could provide any insight because so many of my teachers, you among them, are students of his. I’m wondering if you know what drew him to that world when really he could have taught in any yeshiva and did teach in the highest levels of yeshivas.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

Outstanding question, discussed this with Rav Shapiro several times, several times we got different answers. All of them are true different parts of the tapestry of Torah. The first thing Rav Moshe said is that this is a mesorah and a mission he received from Rav Dessler, Rav Dessler who Rav Moshe said at the end of his life was teaching Torah all around. P’eelim, I think the group was called. That he said after seeing the destruction of Judaism and that Hitler tried to wipe out and kill the entire Jewish nation, we had to go back and teach Torah to the entire Jewish nation. Rav Dessler shared with Rav Moshe the mission of the generation, the mission of the generation in which mashiach is going to come, is clearly teaching Torah in a broader, wider way. Second aspect of why Rav Moshe found an affinity for it was that Rav Moshe became a gadol because of Rav Dessler’s influence, because he asked broad, life-shaking questions.

Torah had to be more profound, Torah had to be deeper than it appeared at first look, and you only get that by asking more profound and more deep and more broad questions.

Rav Moshe was a profoundly deep thinker. And he wanted to get a deeper Torah than most people learn in cheder. Most people, as the Alter of Kelm says, they stop thinking about Torah, when they leave cheder, then they just start learning Gemara and they forget the bigger, broader themes of Torah, Rav Moshe never did. And he wanted people who were mature minds that when a 21, 22-year-old mind comes in from the secular world [it] has big ideas. Now, Torah can be given to him in a broad, mature, and deep, sophisticated manner. And those people who asked those questions were interesting to Rav Moshe. And he wanted to share that with them.

Third aspect is Rav Shapiro, humorously, I think, but challengingly, would always talk to me about that he really doesn’t want to teach Americans. He said if he had his choice, I think this was an instructional comment more than a practical comment. He said, if he has his choice to teach anybody in the world, he would like to teach the Russian refusenik. People who were willing to sacrifice everything for Judaism and think about, and break free of a society that tried to wipe God thoughts out of the mind. Those are the people that he had to devote his life from. And if he couldn’t work with the Russian refuseniks, then he would like to work with Israeli ba’al teshuvahs. Again, there the society works completely against them and they become seen as social parasites. And he said, if I can’t work with Russian ba’alei teshuvah and with the Israeli ba’alei teshuvah, okay. So now you can work with American ba’al teshuvah, at least there’s a little mesiras nefesh, a little sacrifice.

And then he told me that if I can’t work with the… and God, HaKadosh Baruch Hu, decides what we can do. If I don’t get to work with Russian refuseniks or Israeli baal teshuvahs or ba’al teshuvahs, at least let me work with Americans who grew up out of town, where they had to sacrifice for Torah to do something. So he was keeping going, so he really was a person who had great respect for students and great respect for the journey they were on, which always a person of such brilliance and depth, the fact that he respected the student’s journey so much, always powerfully affected me. I think those were the three reasons why he had a great respect and great interest in ba’alei teshuvah. It’s the mission of the generation. They asked questions that were broad and profound, that were the level he wanted the questions to be asked that. And the third is he appreciated their self-sacrifice.

David Bashevkin:

And to this day, though, it’s not quite as sensational or dramatic, but to this day, whenever I make a siyum, based on his guidance, I believe part of the reservoir to you. I always serve fleishig.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

That’s correct.

David Bashevkin:

I always serve fleishig. I remember you told us that story. One thing that we always talk about and that has probably gotten the most attention, is a series that we do every year before Pesach called intergenerational divergence; where we interview children and parents together who have dramatically different religious identities. We had a parent who was a Reform rabbi, Rabbi Robyn Frisch and her son, Benji, who’s learning in Mir. I think he’s back in Lakewood now. And we have them in dialogue together. And it seems that one of the things that you are privy to in your work is this type of religious diversions. And very often, because when somebody comes ba’al teshuvah, they’re uprooting the identity that they were fostered with. What oftentimes happens or can happen, and I’ve seen this happen is parents of ba’al teshuvahwant to see a certain justification in the lives of their children.

Every parent wants to see that all the sacrifices they made. All the more so when you’ve uprooted your life, reinvented your life, changed your life. You want to make sure that your children are able to embody and justify, so to speak, those sacrifices you make.

How do you counsel, what guidance do you give to parents who themselves uprooted, reinvented their life? Mothers, fathers became ba’alei teshuvah midway, and now they’re raising their own children. And it’s so easy. I’m a parent. I was raised in a yeshiva home, but I see it myself. Like you want your children to do that. I could only imagine if I had this dramatic part of my story, what guidance do you give to parents to ensure that their own sacrifices are, so to speak, super-imposed on their children.

Beryl Gershenfeld:

One of the things we do in Machon Shlomo, Machon Yaakov is that we spend three months working in a va’ad of Mussar, focused on knowing yourself. Knowing your strength. Knowing your weaknesses. Recognizing how every person is different. We also talk about recognizing how every time is different. Generations are different. So I think one aspect that helps being a good parent is the appreciation of the fact that no one should have to repeat your story and your vision, your mission in life, is to sit down and recognize the greatness of everybody and their differences.

When you think people have to follow your path and your approach, that’s not recognizing the personality of the people and it’s not recognizing the changing of the times. So that openness, I think, is very powerful. I usually share the Vilna Gaon’s insight that, what’s the end of a good life in Judaism? What’s the ultimate goal?

It’s amazing how the Torah is written, right? We know that the word “sefer” does not mean “sefers,” you know, a book. It’s not a dry academic understanding. The word “sefer” comes to the word “sipur,” Rashi says, so that pulls your heart, it’s drama. So the end of the first sefer of Chumash is Yaakov, looking at 12 sons as he dies and giving each of them a different bracha. I recognize my children’s differences and I recognize it’s my special mission and legacy as a parent to connect them with God, to give a blessing to them and to bring a flow of my connection to God to them to help them achieve what they have to achieve. That’s the end of the first drama of Chumash. In a world of diversity can a parent recognize 12 different paths? And each of those paths realize, we need his breicha, his blessing, his river of flow of energy to help those kids grow.

If that’s not clear enough, we go to the very end of the Torah. What’s the last part of the Torah? Last vision, the Vilna Gaon says, the ultimate good of a human being is Moshe Rabbeinu, Zos Habracha. I’m going to give everyone a blessing and they’re not the same blessing. Each one gets a different blessing, 12 tribes, 12 blessings. If we see a parent as that vision of recognizing differences and my mission as a Jewish parent is to bring out godliness and goodliness to them through a blessing. Through, I think, we break out of our narrowness and see the joy of recognizing different paths; the classic “different strokes for different folks.”

If we see that’s the message of Torah, then we’re there with it. Second idea, that helps us grow with the intergenerational flow of realities is, Rashi, has a profound insight, which I tell everybody that’s just the alef bet of being a parent.

The best way to define a word in Hebrew is usually when it’s used in an unusual setting. In the Chumash, you go: “Ooh, that doesn’t make any sense there. What does it mean?”.

So Yosef says: Tell the brothers, “ani av l’Pharaoh,” I am father to Pharaoh. Look how great I am. Tell my father.

So of course he’s not “av l’Pharaoh.” He’s not Pharaoh’s biological father. So what does it mean? So, I think most people would probably say “av l’Pharaoh.” I’m not going to put you in the spot, Reb David, but most people, every man, Reb David I’m sure understands the right answer. But every man would say, oh, he’s advisor. He’s the wise man. He’s the insight. He gives insight to Pharaoh. He’s the advisor. That is actually what the Ibn Ezra says there. But Rashi, based on the midrash doesn’t say that. The midrash says, “ani av l’Pharaoh,” chaver, u’patro.

I’m a friend. I’m a patron. The mission of being a parent is not being the wisdom behind the throne. It’s not being that advisor. It’s being a chaver, being a friend with your child, you have to develop a chavrus. You have to develop a warmth and emotional connection with your child so there’s not this huge intergenerational gap.

And then number two, it’s amazing. There’s no proper Hebrew term for it seemingly. And he says: “And the second aspect of being a father is being a friend and being a patron.”

Know what a patron means. A patron means: “Ooh, I think your idea is wonderful Reb David, and therefore I’m going to devote time and energy to your vision. I’ll be a patron of your idea.” So if we, as parents, see that our mission is to connect emotionally and understand our children and then be a patron. Rejoice and support them in their bringing out their mission in their special way. Generations will be different, but will be engaged in the process of their being different, expressing their Torah to the world in a unique way.

David Bashevkin:

I had one question. I really want to ask this question because most of what I have benefited from you, over the course of my own life, has been in listening. But there is one article that you wrote many, many years ago. I believe it was in memory of your father, correct? In a journal that no longer exists, but it’s about the-

Beryl Gershenfeld:

I killed it.

David Bashevkin:

The Gemara on Rosh Hashanah that describes the Jewish people being “over k’vnei maron,” before God, has typically translated “like sheep.” It’s an article that I hope that we’ll be able to link to because it is so powerful.

But you have a footnote in that article where you talk about the imagery of the Rambam, where the Rambam describes that the words of Torah is like a golden apple covered in silver lattice, and you take the analogy a step deeper in saying: Words of Torah serve two functions, it needs a gold, which really defines value. Gold is what sets the value for other currencies. And you need this silver lattice around it that kind of is your daily exchange. You don’t come into a convenience store with a bar of gold. The silver is your daily transaction. And I’m curious for you, so much work in yeshivas in the Meor campus movement. What is the gold that drives your daily work, that motivates your own work? And what is the silver?

Because even corresponding with you, I always try to literally bookend with an apology and end with an apology. You’re so busy. You do so much for your talmidim. I’m always meeting people who are connecting and interconnecting with you trying to send messages through behind the classroom to get you on the 18Forty podcast, of course. But I’m curious, what is the gold that so to speak animates your life, defines what it’s about? And what’s the daily silver that keeps you going after all these years?

Beryl Gershenfeld:

The gold is that when I look as again, I look deep into my being and I find the essence of being made in God’s image is a desire to be like God. To help other people grow and recognize their potential and bring out the tzelem elokim. The essential goal is for me to self-actualize and then to help others self-actualize. And the gold is what HaKadosh Baruch Huwants is that if we’re all developing our root of humanity, our root of being Jewish, it’s going to be much better world. I want to be part of that process. The Gemara at the end of Brachot, I share with my students, is the message I usually live by. That’s probably why it’s so hard to contact me. Sometimes Gemara says profoundly at the end of Brachot: “Talmidei chachachim ein lahem menucha, lo b’olam haze v’lo b’olam haba, shene’emar: ‘Yelchu m’chayel l’chayel v’yire elokim b’zion.’” Gemara says that talmidei chacham never have rest. They’re walking from battle to battle.

And even in the world to come, they’re not going to have rest. The Maharal understands that’s because there’s so many ideas in the world to understand that we’re constantly growing and HaKadosh Baruch Hu doesn’t hate talmidei chacham, but there’s a low level joy of the nefesh of resting, of being satisfied. There’s a higher level joy of self-actualization, of engagement, of growing. I want to be part of that self-actualization of that talmid chacham, that there’s always new ideas. There’s always new projects. There’s new influences we have to get. I’m inspired by the ideas. The Gra learns that Gemaradifferently and says it’s about growing as a person. He says that shor ben yomo, cow, the first day as a cow, but human being grows and changes every day, so besides being inspired by the ideals and the ideas, there’s so much [to be] done.