Hanan Schlesinger: ‘From the river to the sea is all Israel and all Palestine’

Zionism asked the Jewish People if they could wield power properly, Rabbi Hanan Schlesinger says. The answer, according to him, is now clear: They cannot.

Summary

References

Hanan Schlesinger: The challenge of our generation that is that past generation was dealing with something the Jewish people have not had for 2000 years, which is power. And it’s a truism that power corrupts. What’s gonna happen when the Jewish people have power, have a state, can have a military? And for me, that’s no longer a question. In other words, the question was, can we use our power ethically? And the answer has been given.

The answer is no.Hello, my name is Hanan Schlesinger. I’m a rabbi, I’m a teacher, and I’m a peace activist. This is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers from 18Forty.

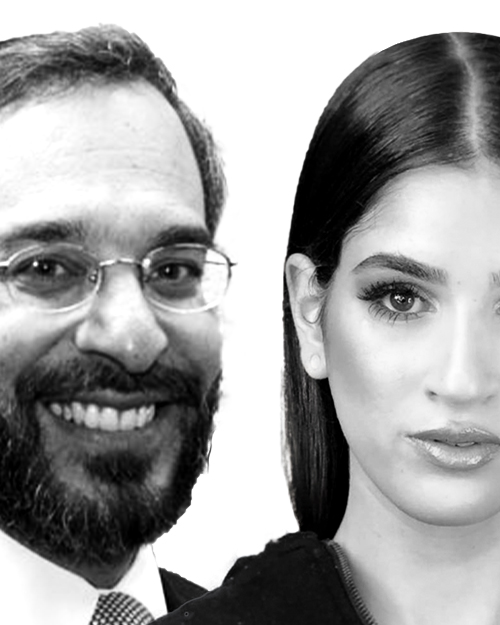

Sruli Fruchter: From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter.

18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore the most critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas war, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So, if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today.I make this point over and over again, but it’s one that I keep coming back to because I think it’s so relevant and it’s I find it particularly so interesting. The people in Israel who we speak to do not just think about the issues that we ask and the topics that we discuss, but they really live them in a way that’s very visceral and relevant to their personal lives.

That’s why I’m always particularly interested when I’m speaking with an activist because the way that they engage with these issues is also with a very different dynamic than many people may be used to. Today’s interview is with Hanan Schlesinger, one of the founders of Roots Shorashim Judur, a Palestinian-Israeli grassroots initiative for, quote, understanding, non-violence, and transformation. Hanan is the director of international relations for Roots and founded the American Friends of Roots, which is a multi-faith organization to supporting their work here in Israel. The whole idea of Roots, which I actually had gone to during an advocacy trip that I was on in high school, is bringing coexistence and dialogue to Palestinians and Israelis to help transform the potential of peace between the two peoples.

Prior to the founding of Roots, Hanan spent his whole career teaching Jewish studies in various seminaries, colleges in the Jerusalem area. Beginning in late 2013, he describes how he felt, quote, transformed by his encounters with Palestinians and the Palestinian people, and really shifted his perspective on what he viewed as the core fundamental issues pulling Israelis and Palestinians apart in the land and what the potential for hope and peace looked like and where that would come from. He has lived in Alon Shvut for 40 years, grew up in a secular Jewish family, and by the end of high school began his observant journey all by himself. In Dallas about 17 years ago, was when he began to become involved in interfaith work with Christians and then with Muslims, and there he founded Faiths in Conversation, which is a framework for Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theological dialogue.

But it was really that 2013 turning point that set him on the path he is on right now. Hanan is a member of the RCA and the International Rabbinic Fellowship as well as Beit Hillel, an Israeli Rabbinic Association. He was honored in 2013 and 2014 as the Memnosine Institute Interfaith Scholar. It was very interesting to speak with Hanan to hear his views, to hear the complicated, messy, nuanced, and honest, raw experiences and perspectives that he shares.

And I really enjoyed this conversation. So, without further ado, before we get into the interview, if you have questions you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, please shoot us an email at info@18Forty.org and be sure to subscribe and share with friends so that we can reach new listeners. Big things are coming to 18Forty as we are in our fifth year since our founding. But until then, and stay tuned for that, please enjoy my interview.

And now, actually, without further ado, here is 18 Questions with Hanan Schlesinger.So, we’ll begin where we always do. As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

Hanan Schlesinger: I’m feeling despondent, almost despairing. I am deeply disillusioned by what Zionism has become.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you mean by that?

Hanan Schlesinger: I have lived within the Jewish story for most of my life.

I’ve lived so deep in the Jewish story. Jewish story that I didn’t even know I was living in the Jewish story. It was the only story I knew. I wasn’t seeing it from the outside, I was seeing it from the inside.

And I guess we believe, we Jews have always believed that we’re special, that there are things that happen, could happen, do happen to other nations, other peoples that couldn’t happen to us. And it seems to me that terrible things have happened to us. What I mean is terrible developments in the moral and spiritual fiber of us Israeli Jews as a collective and as individuals. I think that we’ve proven ourselves not to be any special, any different than any other.

Sruli Fruchter: By special you mean more morally or spiritually?

Hanan Schlesinger: I mean morally or spiritually better. Certainly not. And like many of my friends, the paradigms that we’ve lived our lives within have been shattered.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Which paradigms is that?

Hanan Schlesinger: I suppose that we had a deep, deep sense of conviction that through Zionism we are doing good for the Jewish people. We’re entering a new era, we are uplifting the Jewish people, and that our uplift of the Jewish people will uplift at least after time the world. We’ll be bringing to some type, some type of tikkun olam, some type of reishit tzmichat geulateinu, some type of path towards the fulfillment of the visions of Isaiah. And that hasn’t happened.

And I think that Zionism has done tremendous good for the Jewish people, but I think it’s also done tremendous bad for the Jewish people. I think it’s done some bad things for parts of the world.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you be more specific when you say that it’s done?

Hanan Schlesinger: It’s clear to me that I’m not being specific. I’ll just,

Sruli Fruchter: No, no, that’s fine.

That’s fine.

Hanan Schlesinger: just beginning to get into it.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, yeah, of course. And we have more questions to go.

But I’m curious what you mean by that when you say that Zionism has done some good things for the Jewish people, for the world, and that it has also done some bad things to the Jewish people and to the world.

Hanan Schlesinger: So I don’t think I said that Zionism has done good things for the world, but that was part of our hope, that’s for the eventual fulfillment. So the good things we’ve done for the Jewish people, that Zionism has done for the Jewish people, uh, to me almost don’t have to be enunciated, but I understand they do have to be enunciated. We have returned the Jewish people to the, to the stage of history.

We have created an unbelievably vibrant, beautiful state with good governance. We’ve brought Jewish culture to a flourishing spiritually, philosophically, religiously, that we couldn’t have imagined a hundred years ago. We’ve saved hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives. We’ve certainly saved parts of the Jewish people from some type of assimilation.

We’ve brought a pride and a vibrancy to Judaism. All that is of course wonderful. That’s, that was my whole life. My whole life was Zionism, aliyah, Jewish education, teaching Torah.

But on the other side of the coin, the, the bad, the evil that we’ve done, already, uh, more than 50 years ago, Jewish thinkers, I mean the school of Rabbi David Hartman and others, were teaching and saying that the challenge of our generation, that is that past generation, was dealing with something the Jewish people have not had for 2,000 years, which is power. And it’s a truism that power corrupts. What’s going to happen when the Jewish people have power, have a state, can have a military? And for me, that’s no longer a question. In other words, the question was, can we use our power ethically? And the answer has been given.

The answer’s no. We, I wouldn’t say we, it’s not that we cannot, but we didn’t. We didn’t use our power ethically. And on that’s caused a a moral, spiritual crisis for me.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. So I want to turn to the power, so to speak, that’s playing out in this war right now. What do you think has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in the war against Hamas?

Hanan Schlesinger: What has been the greatest failure, you said?

Sruli Fruchter: Greatest success.

Hanan Schlesinger: success and greatest mistake, or greatest failure.

Sruli Fruchter: The greatest failure’s been the war itself. I already spoke publicly three weeks, four weeks after October 7th. What I said then, I believe to this very day, which is that war, and specifically that war, this war, perhaps, perhaps, under certain circumstances can be justified, but only if there is a possibility that the war will lead to peace, that the war will lead to a political horizon that could potentially bring peace and security to the state of Israel. But since I knew, and this the government said clearly, that it doesn’t have a political plan for the day after, it doesn’t have a vision of how we, the state of Israel, can live in a secure peace in the Middle East.

Therefore, without that, the war is fruitless and meaningless. And that, it was clear to me then that thousands of people are going to die, both Israelis and Palestinians, for no benefit. And to live with that deep understanding is extremely difficult. It’s my neighbors, it’s my extended Jewish family who are being killed.

It’s human beings who I know their families on on both sides of this conflict, and I don’t see that it’s bringing the state of Israel or the Jewish people any greater security or prosperity.

Hanan Schlesinger: Was there any success or benefit that you saw to the war? I mean you mentioned that a few weeks after it first began, that you then denounced that it’s going to be fruitless.

Sruli Fruchter: That’s a really hard question. Let me think about that.

Any benefit.

Hanan Schlesinger: And and partially why I’m asking as well, I mean, we ask this question in general, but I think one of the things that’s on my mind, and I think that many would feel and I’m sure you’ve encountered, is that after October 7th, the question becomes if not war, then what? Meaning, I think people have had different conversations between the relevance or the necessity of the war at different stages, meaning October 2023, May 2024, June 2025. But in at least the beginning of October 7th, it felt that, and it seemed like Israeli society between right, left, center was in, for the most part, pretty strong consensus that war against Hamas was necessary, if not for peace, then at least for security and for safety and for, at that point, bringing back the chatufim. How did you view it?

Sruli Fruchter: I am definitely an outlier.

I’m one of the few, certainly in the religious setting in which I live, one of the few who took a position against the war. I didn’t think and I don’t think that the war is helpful in bring back the hostages. I don’t see any good that it’s done for the State of Israel. I see only death and destruction and further trauma and pain and generations of potential terrorists being created.

I shouldn’t even say potential, I should say terrorists being created. And now you have two million people in Gaza who have no hope for the future, who are full of rage and anguish and pain and, in some cases, probably, or certainly, a desire and dreams of revenge. That hasn’t brought us anywhere. I can’t see any good that has come from the war.

So you asked me what would have been an alternative path. So a little bit of background, can’t give a lot of background. I basically say that Hamas is two things, in their own consciousness and in reality. Hamas is a violent, extremist, antisemitic, terrorist organization based on a fundamentalist, theological, Islamic ideology.

And in the form that it’s become, probably it’s impossible to negotiate with. And secondly, Hamas is an expression of Palestinian resistance against injustice and perceived injustice going back almost a hundred years. So given those two aspects of Hamas,

Hanan Schlesinger: what could have been done the day after October 7th? I don’t think that’s the right question. I think the right question is what could have been done the day before October 7th, because I think that Medinat Yisrael could have behaved in a different fashion such that October 7th would not have occurred.

Let’s be careful, let’s not say the day before October 7th, but that was a metaphor meaning before October 7th. There were many times in which Hamas could have been negotiated with before it morphed into the Hamas of October 7th. Years before and decades before. There were many peace proposals on the table.

I have a an acquaintance Gershon Baskin, who was the Israeli negotiator in the Gilad Shalit negotiations who brought about the release of Gilad Shalit in exchange for too many Palestinian prisoners. But he has had back channel connections with Hamas all these years. He presented certain potential plans to Netanyahu, to the government, that were rejected. There was a Saudi peace initiative.

There’ve been many, many things happening on the ground. There was almost time. Israel, I can’t say for certain, of course, that there could have been successful peace negotiations, but there were openings that we decided not to take. Now, I’m not saying, obviously I’m not saying, what I’m about to say doesn’t have to be said, but perhaps there are listeners that need it to be said.

I’m not saying that all the fault, God forbid, lies with the Jewish people, but some of it does. Enough of it does and my my responsibility is for the Jewish people. And when we fail ourselves, I am distraught.

Sruli Fruchter: How have your religious views changed since October 7th?

Hanan Schlesinger: How have my religious views changed since October 7th? I don’t think my religious views have changed since October 7th, but the aftermath of October 7th, the way that Israeli politicians have expressed themselves, especially but not only religious politicians, and the way that some Israeli soldiers have behaved, especially religious soldiers, but not only, has reinforced for me what I have taught for decades, which is that we have certain elements within our tradition that are conducive to racism or border on racism, and that may, that have within them the potential to cause us, we Jews who believe in them, to behave in fashions that in my eyes go against divine morality.

And that’s played out. It’s played out before October 7th, but even more since October 7th. And I think that part of the efforts that we Jews have to be involved in to create a better future have to do with interpretation and reinterpretation of elements of our tradition. This is being done to a certain degree within Ohr Torah Stone today, the the institutions founded by Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, now headed by Rabbi Kenneth Brander.

Within Ohr Torah Stone, there’s the center, I think for

Sruli Fruchter: Dialogue…Judaism and humanity, or

Hanan Schlesinger: Judaism and the Humanity. Yes, thank you. Headed by my colleague and my mentor, Rabbi Yaakov Nagen, and they understand this deeply and they’re working in this direction. I just want to say parenthetically that on many matters, my criticisms of the way Jewish tradition has been interpreted go beyond what Rabbi Yaakov Nagen holds.

I don’t want anyone to think that he is as despondent or as disappointed or as

Sruli Fruchter: He was one of our early guests actually on the podcast.

Hanan Schlesinger: So I think he’s, but I think he’s fantastic. Even though I go further than he does in many matters.

Sruli Fruchter: So I want to shift a little bit away from the war specifically and October 7th and speak more broadly about your views on Israeli society and the different structures within it.

What do you look for when deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

Hanan Schlesinger: What do I look for? I look for, or let’s say I would look for, a party that first and foremost espouses a stance of morality and and social justice.

Sruli Fruchter: Have you found such a party?

Hanan Schlesinger: There was Meimad, the party founded by my my mentor and my teacher. `Yehuda Amital`, may his memory be a blessing. And I have not found anything like it or like him since his passing.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more about how he how he was as your mentor?

Hanan Schlesinger: How he was as my mentor. So the question how I was as my mentor, `Rav Amital`, many, many, many, many people had the sense that when he was speaking to a group of 10 people or 100 people, a thousand people, he was looking and speaking right at you. There was a sense that he understood you, that he spoke to your heart and not just to your intellect. He spoke to your humanity, to your frailties, to your hopes, to your, to your dreams.

And one of the many, many, many things he taught us is that `derech eretz kadma laTorah`. And I’m to translate that, already is taking a position what it means. But for `Rav Amital`, it was clear that the `Torah` is based upon, is founded upon morality. Earlier, just five minutes ago, I used the term divine morality.

I could have said universal morality. For `Rav Amital`, it was the same thing. That `Hakadosh Baruch Hu`, God, is fundamentally moral. And the `Torah` is based upon, assumes the basic human divine morality, universal morality, and then comes to build upon it.

It was clear to `Rav Amital` that when `Avraham`, Abraham, says to God, `shofet kol ha’aretz lo ya’aseh mishpat`, the judge of all the world won’t do justice. This is when `Avraham` is arguing with God before the destruction of the city of `Sdom`. It was clear to him, was clear to all of us in the `Beit Midrash`, in the study hall, according to `Rav Amital`, that `Avraham` assumes that God is moral before he’s anything else and and the `Torah` assumes that God is moral before he’s anything else. And when the `Torah` is given, it is based upon the foundation of that basic `menschlichkeit`.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: And we should never, ever, ever think that the `Torah` comes to abrogate or to supersede that divine that divine human universal morality. And one of the basic and many issues with the way Judaism is being interpreted and lived and applied today in the state of Israel by people who look like me with a beard and a and a `kippah` and `tzitzit`, is that it’s being interpreted and lived and applied according to the opposite approach in Jewish philosophy, which is that there’s no such thing as divine morality, human morality, universal morality. The only thing is the `mitzvot`, the only thing is the `Torah`.

And anything that’s not written in the simple meaning of the `Torah` has no validity, no force, doesn’t bind us. And and there’s no such thing according to this approach as human morality. It’s divine morality, universal morality. It’s called what those who disagree with me, they say it’s Christian.

And if you adapt any standards that are that are based on universal morality or or what’s called natural law, you’re just adopting the `goyish` way. That for me that’s one of the foundations of the the moral morass that we in the state of Israel find find ourselves in today.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. When it comes to the state of Israel, which is more important, Judaism or democracy?

Hanan Schlesinger: It sounds to me like it’s comparing apples and oranges.

Judaism is a set of values, of ultimate, of ultimate principles. Whereas democracy is a means, a means of government. Democracy can bring us to a political system based on Jewish values, or it can bring us to to tragedy, to great immorality. Now, if you ask me differently, not Judaism and democracy, but Judaism and human rights, for example, I’ll give you a different answer.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. You want to ask that question?

Hanan Schlesinger: I’m happy you ask that question. I’d be happy to answer that question. Uh, for me, uh, human rights, we’d of course have to define and there’s a lot to say here, but in general, a good part of what today is called human rights falls under the rubric of natural law, of universal morality.

So then if you ask me what’s more important, human rights in the sense I just defined it or Judaism, I would say that’s like asking me what’s more important, `derech eretz` or `Torah`. Uh, but we already said a few seconds ago that according to the `Torah`, `derech eretz kadma laTorah`. according to the Torah, universal human morality is the foundation on which Torah is constructed. By the way, this reminds me that in addition to my Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Amitai who whose waters I drank from, the other Rosh Yeshiva in the yeshiva I studied in, Yeshiva Har Etzion, was Rav Lichtenstein.

And Rav Lichtenstein had wrote a very, very, very famous article on this subject, exactly. Does the Torah recognize what is it?

Sruli Fruchter: Ethics beyond?

Hanan Schlesinger: Ethics outside the framework of the Torah.

Sruli Fruchter: Or I guess outside of Halacha.

Hanan Schlesinger: Yes.

Yeah. And that’s exactly the subject we’re talking about right now.

Sruli Fruchter: So, on the topic of governance and society in Israel, should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

Hanan Schlesinger: That’s a complicated question that has to be divided into, excuse me, component parts, but if I had to give a one word answer, the answer is yes.

Sruli Fruchter: What makes that complicated for you?

Hanan Schlesinger: We have here in the State of Israel two values or needs that are in tension.

One is the principle of Tzelem Elokim of the fundamental divinity of every human being, which implies the fundamental equality of every human being, the need to grant dignity and respect and freedom of choice to all people living within the borders of the state. Notice I didn’t say citizens, I said all people living within the borders of the state. And on the other hand, we have a need for a Jewish state. Almost by definition, a Jewish state is going to favor those who are part of the Jewish people.

Sruli Fruchter: Are you saying that as it how it should be, or that’s just how it is?

Hanan Schlesinger: That’s the way it should be. That’s the way it should be. And how you work out that that tension is difficult, complicated. It seems to me that there are better ways to work it out than the way the State of Israel has worked out until now.

Most, the vast majority of Israeli Jews don’t know, and the vast majority of Jews around the world don’t know the discrimination that Palestinian Israelis experience legally, de jure and de facto.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more about that?

Hanan Schlesinger: Yeah. One of the major things that Jews in Israel and outside of Israel don’t know about the experience of Palestinian Israelis is that everyone knows that to a very large degree, they live in their own towns and villages. Recently, we’ve always had a few mixed cities.

Today we have a few more. And in those Palestinian Israeli municipalities, allocation of land since 1948 has been extremely, extremely, extremely limited. Actually, if I use the phrase allocation, then there’s been no allocations, there’s rather been the the cutting off of chunks of land that had been part of the the general borders of many, many Palestinian municipalities. So there’s no room to build.

And that means that families can’t stay together. That means overcrowding of those who do want to stay together. And then when Palestinian Israelis are forced to move to quote unquote Jewish cities, take for example Karmiel or take for example Afula, then they suffer discrimination. One of the many expressions of discrimination is that although according to the law there are state schools Jewish and state school Arab and a state school Jewish religious, but the municipalities have by and large prevented the Palestinians from creating state Arab schools in in those municipalities.

I think Afula and Karmiel are two examples. But I’m not up to date exactly on the details. And then there’s just the general discrimination of against Arabs because number one, because they’re not Jews and number two, because they’re Arabs. I know many, many, many Palestinian Israelis who were afraid to speak Arabic on the streets, especially since October 7th, lest they will be suspected of being terrorists.

I there are many cases in which Palestinian Israelis are denied the opportunity to rent an apartment in Tel Aviv because it turns out that the owners don’t want to rent to to Palestinians. Those are some examples.

Sruli Fruchter: Earlier on in the interview, you were speaking about how you’ve become rather afraid and pessimistic about what Zionism has become. Do you consider yourself a Zionist?

Hanan Schlesinger: I certainly consider myself a Zionist.

But I consider myself a conflicted Zionist. An anguished Zionist. But I’m not that much concerned with labels. I’m concerned with the facts on the ground.

Sruli Fruchter: So, now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

Hanan Schlesinger: That’s of course a very, very good question. What’s the purpose of Zionism? Well, when I think of Zionism, I think of religious Zionism. That’s the world in which I live. That’s my constituency.

And when I say of course religious Zionism, I don’t mean the political party. I mean the people in the movement. And we are, we need to be involved in nurturing a Judaism that is comfortable in its land, that’s creating an indigenous Jewish religious culture that, going back to what I said earlier about dealing with power, that one of the major issues here in Zionist thought is how do we deal with Jewish power, which in this case means, at this stage in Jewish history, how do we deal with the abuse of Jewish power? How do we, how do we fix that? How do we go back to a Judaism rooted in the sources and rooted in the land that doesn’t skip over two thousand years of Jewish intellectual history. And what I’m saying is that a indigenous Jewish culture rooted in Jewish sources that doesn’t behave, doesn’t think and doesn’t behave as if we are the Israelites entering the land under Yehoshua, Joshua, and doesn’t behave as if the Palestinians are the seven Canaanite nations that have to be exterminated.

And that means we have to take into account the Talmudic and the Halakhic discourse that has interpreted Torah since then. And of course, every religious Jew knows that according to Rabbinic thought, the Torah, meaning the scripture, must and always be interpreted through Jewish tradition and not directly.

Sruli Fruchter: One of the things that I think people find difficult with that is that you do have many, like a plethora of Israeli and Jewish thinkers who do in fact interpret Jewish history and Jewish tradition and the sources and so on and come to very different conclusions.

Hanan Schlesinger: Absolutely.

Sruli Fruchter: You know, whether that’s Rav Shaul Yisraeli, or whether that is different people in the Knesset or other thinkers in mainstream Zionist or, you know, Chardal thought.

Hanan Schlesinger: Yes.

Sruli Fruchter: How do you understand that?

Hanan Schlesinger: Okay, so here’s something really important. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to say this.

Many of my Palestinian Muslim colleagues who are fighting for peace and reconciliation and are fighting for their interpretation of Islam, which is accepting of the Jewish people and Jewish people’s connection to the land and who see reconciliation with the Jewish people and living together with the Jewish people in this land between the river and the sea as fundamental to Islam. I would say almost all of them take the position that their moral and reconciliatory interpretation of Islam is the true Islam, the only Islam. And all the other Muslim thinkers are wrong. ISIS is wrong and Daesh is wrong and this Islamic brotherhood is wrong and Hamas is wrong, and the only true Islam is the Islam that my friends espouse.

And I say to them, how can you make that claim that your Islam is the only true Islam? Ninety percent of Islamic thinkers in the Middle East, I’m sorry, I don’t know if it’s 90 percent, 80 percent, I don’t know, 70 percent, even if it’s 50 percent, disagree with you. How can you be so certain that your Islam is the only true Islam? And the same claim I make against them, I make towards myself. In other words, I cannot claim and I do not claim—

Sruli Fruchter: And so how do you respond to that claim?

Hanan Schlesinger: I do not make the claim that my Judaism is the only true Judaism, that my interpretation or that of thinkers that I follow in the footsteps, whether it’s Rav Amitai or Rav Lichtenstein or Rav Yaakov Nagen or Rav Benny Lau and others, or Rav David Rosen, I cannot claim that our Judaism is the only true Judaism. I cannot.

I have to admit that we’re in the minority. But more than that I have to admit that other thinkers have just as much of a leg to stand on within traditional Jewish sources as I do. And furthermore, I even have to admit that Judaism is as Judaism does. I take that from my mentor and friend Rav Brad Hirschfield, the executive vice president of CLAL in New York.

You can’t claim that a religion is other than the way it plays itself out in history in every generation. is what it is. And in this, and therefore Judaism is as Judaism does. And in this generation, Judaism is things that I call immoral.

It is, I have to admit that. So now what was the question?

Sruli Fruchter: So like how do you respond to that claim? Meaning then from what you were saying before I understood.

Hanan Schlesinger: Okay. So my response is that the Judaism of Betzalel Smotrich or of Itamar Ben-Gvir or of Rav Dov Lior or hundreds and thousands of other important, knowledgeable, well-founded Jewish thinkers, their interpretation is as much founded in the sources as mine is.

It is. I have to admit that. I’m sorry about that. I’m even ashamed of it, but I have to admit it.

And I can only claim not that my interpretation or the interpretation of the thinkers I mentioned that I follow in their footsteps, I can’t claim that our Judaism is truer or more authentic, but I can claim that our Judaism is also true and also authentic. Eilu v’eilu divrei Elohim chayim. These and those are the words of of the living God. There are many interpretations of Judaism and I want my Judaism to win in the competition in the arena of Jewish ideas.

I want it to win. And I think it would be better for the world and better for the Jewish people. But I have to admit that presently my interpretation is losing.

Sruli Fruchter: Is opposing Zionism inherently anti-Semitic?

Hanan Schlesinger: Of course not.

Or maybe I should say, of course not. I understand that’s a question’s on the table today, but to me it’s almost an incomprehensible question.

Sruli Fruchter: I’m curious, did you always think that and can you elaborate why?

Hanan Schlesinger: I probably didn’t always think that because I early in my life had narrower horizons and I didn’t see the larger picture. Okay, so let’s try and answer the question, and this of course is complicated.

We have to go back. I’m not going to define antisemitism. I’m going to assume it’s like pornography, that we know it when we see it. Although in the end of my words, I’ll I’ll add there that sometimes people see it and I don’t think it’s there.

Zionism for me is and was the national liberation movement of the Jewish people that has that has had as one of its goals to bring the Jews out of exile and bring us back home to a independent Jewish state in which we can control our own destiny. And to a large degree, Zionism has succeeded in doing that. It’s an ongoing process, but we’ve succeeded. I would say gloriously so.

On the other hand, at the same time that Zionism was and is the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, it also expressed itself in the mode of doing things of the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, up until the the middle of the 20th century, which was colonialism. That was the only way that the world knew of establishing I want to be more careful. It was one of the major modes in which in which masses of people were moved to a different part of the world and established there self-rule and self-government. So Zionism expressed itself to a certain degree through the modes of colonialism, sometimes by intention but usually not so.

And like most or perhaps all colonial movements, Zionism had certain negative consequences for the local inhabitants who were there before the Jewish people came back to our land. So Palestinians have suffered, have suffered greatly. By the way, part of the suffering is not only a result of the way Zionism expressed itself through those colonial means, but also as a result of certain attitudes and behaviors of the local Palestinians. Could we Jews have done it differently? I don’t know.

Can the Palestinian— Could the Palestinians have done it differently? I don’t know. But when I say I don’t know, I mean that really. In other words, it could have been that we could have done it differently. It could have been that they have done it differently.

I’m not sure. I just don’t know. But in any case,

Sruli Fruchter: So meaning opposing that is not, you don’t view that as anti-Semitic because there were negative consequences for others.

Hanan Schlesinger: So for for Palestinians today, what they know about Zionism is not what’s written in our books and not what’s in my mind or your mind or anyone’s mind.

They know that in point of fact, on the ground, tachles, it has destroyed their culture and their livelihoods and and their land. Again, partly for their because of their own ways of reacting. So to oppose that is not anti-Semitic at all. I oppose, I oppose those expressions and results of Zionism, and just about all Palestinians oppose the fact that their grandmother was killed or that their grandfather lost his land.

They opposed Zionism as they see it, and some, I don’t know if it’s many, but some Palestinians are very anti-Zionist and have a deep, deep appreciation for the Jewish people and for the Torah.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. Should Israel be a religious state?

Hanan Schlesinger: We’d have to define that before I answer it. I would hope that Israel would be a state that is, a state that provides a platform for the fullest expression of Jewish values.

Let me say paradoxically that the best Jewish religious state will not be a Jewish religious state.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: Because when you give, to use the words of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, when you give Judaism power, you take away influence. And I would like Judaism, I’m paraphrasing Rabbi Sacks, to have maximum influence, which means minimum power.

When we say power, we mean hard power, we mean political power, we mean coercive power. When we say influence, we mean soft power. We mean the ability to persuade and to encourage Jews to express the fullness of Jewish value and practice in their daily lives.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: That’s not accomplished by coercive religious legislation.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. I know that through much of your peace work and this may be a paraphrase or a direct quote of Rav Froman, that if religion is part of the problem, then religion must be part of the solution.

Hanan Schlesinger: Thanks for saying that.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you believe that to be so, and if that’s the case, what does that look like in a practical way?

Hanan Schlesinger: Yeah, we’ve actually been talking around that subject for quite a bit during this podcast. So Rav Froman did say that if religion is part of the problem, then religion must be part of the solution. And when he said if, he meant that it is part of the problem. And when he said religion, he meant Judaism.

Although not only Judaism. Islam is also a big part of the problem. So, this goes back to things we said earlier. Certainly, certainly, certainly, I believe in Torah she’ba’al peh, as I believe in Jewish interpretation.

We live Rabbinic Judaism which is based on interpretation of 2,000 years of reading and rereading and reading the reading in the reading of generations of interpretation. That’s Torah she’ba’al peh, and the rabbis already told us that there is no Judaism without Torah she’ba’al peh, that Judaism is not about doing just what the Tanakh says, what the Bible says, it’s about doing what the Bible says on the basis of generations upon generations of a Jewish interpretation. And now, in the 20th and 21st centuries, I’m going to say something a little bit complicated. One of the results of the return to the land, the return to the realism of Eretz Yisrael, of land of Israel, of of living on the the land that our forefathers walked upon, drinking from the the waters that come out of, that spring from the land of Israel, living in this holy land has returned us to re-looking at the Bible and reconnecting to the Bible on a level of of realism of and this return to the verses of the Bible is very, very invigorating and empowering and beautiful and terribly dangerous and tragic at the same time.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: Because what’s happened is to a certain degree that we are unconsciously and consciously forgetting or putting aside the 2,000 years of tradition and going back to the simple meaning of the verses. That’s what I had said earlier, that for some of the Jews today that I disagree with, they’re living as if we today are the Israelites conquering the land under Joshua and the Palestine, Palestinians are the the Canaanites. Now, according to Jewish law, through 2,000 years of interpretation, that’s wrong, that’s forbidden, that’s that’s not true.

But we are leapfrogging over those efforts of our rabbis to, how do you say it? l’aden. to to make more

Sruli Fruchter: To like soften or

Hanan Schlesinger: To soften, to soften, to make more moral some of the simple meaning of the biblical scripture, and that is tragic. So, you so, the question was, if religion is part of the problem, religion must be part of the solution. Yes, religion is part of the problem to a large degree because of the leapfrogging over Jewish tradition and going back to the simple meaning of scripture.

And what we have to do today is number one, go back to an interpreting Judaism through the lens of tradition, of the oral law of the rabbis and not just the scripture itself. And we have to continue the process that our rabbis began of continually trying to soften is not the right word, to uh, don’t have a good word for le’aden, to bring the way we interpret Judaism more in line with the fundamental values of of Judaism.

Sruli Fruchter: So so on that note, do you think that the State of Israel is part of the final redemption?

Hanan Schlesinger: You gave me an out when you said part. Of course it’s part.

The question is what part.

Sruli Fruchter: Is it Yeah, you tell me.

Hanan Schlesinger: I believe that the State of Israel could be potentially, part, not all, part of the redemption. It could be but it might not be.

Part of, but not all of, a stage. The Jewish people today, what is it, 49% of the Jewish people is is back in the land of Israel. That’s one element, one of many, many elements of of redemption. Depending on how we behave morally and in real politic, the State of Israel could be part of the beginning stages of a continuum that brings full redemption to the Jewish people and to the world, or it could be destroyed from outside or from within.

For me there’s absolutely absolutely no guarantees. And I also believe that the belief that there are guarantees is part of the guarantee that it won’t be. In other words, a sense that this is guaranteed part of the redemption leads to the misuse of power, leads to cockiness, leads to haughtiness, and that leads to a corrupting of our basic values and may lead to redemption. I’m sorry, to uh destruction.

Sruli Fruchter: Uh huh. One of the things that I’m struggling with and I and I assume you probably encounter this when you’re speaking to other people as well is that, you know, throughout this interview or this conversation, we’re speaking a lot about different ideas and, you know, theories of the conflict, of Israelis, of Palestinians, of Zionism and so on. And it almost feels as if it’s a little bit divorced from the reality that we’re facing now. Meaning, post October 7th, where I think for many, especially many on the left, they felt a very strong disillusionment with the prospects of peace and of any actual resolution.

And for many on the right, it was the worst confirmation of many of their fears. And where we find ourselves today in June 2025 as the war continues on is, you know, vast majority of Palestinians in Gaza were, you know, in polls say that they supported October 7th. And I believe in a Penn State poll that came out recently, 82% of Israelis said that they support expulsion of Palestinians in Gaza. With like all of this reality in front of us, how do you think and deal with that? Like, do you think that peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Hanan Schlesinger: I think that peace between Israelis and Palestinians most probably will not happen in my lifetime, but I also think that it is possible within my lifetime.

It’s not probable, but it’s possible.

Sruli Fruchter: Has this reality changed in any way how you view the situation?

Hanan Schlesinger: I have met many people on the right and on the left who say that if October 7th and its aftermath has not fundamentally changed how you view reality, then you don’t know, don’t know where you’re living. And I hold exactly the opposite. I hold that there was nothing in October 7th or the aftermath that didn’t sprout organically from the reality from beforehand.

I’m not saying I’m a prophet that I could have, uh,

Sruli Fruchter: You could have foreseen it, but but but in hindsight, you know, the the seeds were there.

Hanan Schlesinger: Not improbable. What’s changed since October 7th is simply the understanding of how far away we are from from peace and reconciliation, how difficult it will be to get there. And I’m talking about the social psychological difficulty.

That there is so much trauma on both sides and so much need for revenge and so much blindness to the humanity and the identity of the other side, that it seems close to, but not impossible. But we know of the conflicts around the world that have been solved. We know that there are extreme changes overnight in politics sometimes. So there’s a possibility.

And my responsibility is to work towards that possibility, even though it’s improbable. And and also, as as we all know, when there is no hope for things to get better, then things cannot get better for so-called psychosocial psychological reasons. And therefore the propagation of hope is actually a very, very, very practical and realistic need. And part of my job is to propagate hope within me so that I can propagate hope among others.

Sruli Fruchter: And I assume you’re referring to your work at Roots, the dialogue center and other peace work. Can you talk more about that briefly?

Hanan Schlesinger: Yeah, briefly, Roots is the Israeli-Palestinian grassroots initiative for understanding, nonviolence, and transformation. We’re created 11 years ago, I was one of the co-founders, in order to bring together local Israelis and local Palestinians in the West Bank, Judea and Samaria, specifically in the Gush Etzion area, which is south of Jerusalem, between Bethlehem and Hevron. And there, we created the only joint Israeli-Palestinian community center.

It’s called the Dignity Center, the only place in the whole of Judea and Samaria where Israelis and Palestinians, local people can and do meet each other before the war, almost every day. So we have there photography workshops, we had there music therapy, we had there trauma therapy, we had there playback storytelling, we had summer camp, day camp. We had the programs for little kids, singing and arts and crafts. We had for high school kids, our youth movement.

We had interfaith dialogue, we had monthly lectures on the other side’s culture and religion. And we did do a lot of humanizing of the other side in both directions, but we always always emphasized that humanizing the other is not enough. It’s not enough for Israelis to see Palestinians as human beings and it’s not enough for Palestinians to see Israelis as human beings. You have to go further.

And the second level is called identity reconciliation. That Palestinians have to come face to face with, have to come to terms with, have to recognize and respect for Jewish identity. Which means that the Jewish people are a people, not a religion, not only a religion, we are a people. And we have a connection to this land.

We have a deep, deep historical connection to this land. This is the land of Israel from the river to the sea. Palestinians have to recognize that, and Israelis have to recognize Palestinian identity, which is that the Palestinians are a people, and they have a deep, deep historical connection to this land between the river and the sea. Which means, and this is very hard for many Israelis and many Jews, many Palestinians to hear, that the land between the river and the sea, the Jordan river and the Mediterranean Sea, has two identities.

It’s all Israel and it’s all Palestine. That’s historically. That’s not politics, that’s history, that’s identity. That Mother Earth, the Holy Land between the river and the sea, gave birth to two children.

In Jewish tradition, right, we talk about Yitzhak, uh, saying in English, Isaac in English, and uh and Yishmael, English, I don’t know how you say it.

Sruli Fruchter: Uh, Ishmael, I don’t know.

Hanan Schlesinger: Yeah, I guess so. Uh, and these two children who represent figuratively, typologically, the Jewish people and the Palestinian people, they’re brothers, they’re siblings, they’re born to the same mother.

And presently, we’ve been fighting over who’s legitimate child of of that mother. And I come and claim and Roots comes and claims that both children are real, legitimate, beloved children of that mother, and we have to share her.

Sruli Fruchter: How does your work fit into the reality that we’re in right now? Meaning where I would understand where from for both Israelis and for Palestinians, there actually is no interest in dialogue, not from necessarily an ideological opposition, but from a reality position where for Israelis who are going out to war, who are losing soldiers, who are still, you know, suffering on a national level, they’re not interested in now trying to speak to individuals that’s not going to have practical change. And then for Palestinians, specifically those in Gaza or in the West Bank, who are struggling with whether it’s, you know, the ongoing war and how it affects them on a day-to-day basis, or military options in the West Bank, where dialogue may and and I, you know, I’ve seen online from both sides, right and left, Palestinians and Israelis, critiquing this type of work right now, that it’s not really doing anything for their lived reality in this moment.

Has that been something that you’ve encountered?

Hanan Schlesinger: Yes. Indeed, the work of Roots, I mean, the people-to-people work, which before October 7th was the major part of our work, is not doing anything for the immediate lived needs of the people on the ground. The people-to-people work meets from my perspective, the psychological, moral needs of the people on the ground in the present and the future. needs.

What I mean is that I’ve heard hundreds of Palestinian parents and Israeli parents tell me that they don’t want their children growing up to hate the other side. And in our summer camp or in the kids’ activities, kids come home without that hate that’s in the atmosphere of the cultures of both sides. That’s the meeting of a real immediate, not physical need, but a moral, spiritual need. And then of course people-to-people work meets the future needs where we create the reconciliation which is a necessary, crucial, and necessary component of a future peace settlement.

There won’t be a political peace settlement in this land, a political settlement without a large degree of the people on both sides being willing and and interested in that peace settlement, which means there must be reconciliation of our identities. What I called earlier, identity reconciliation. But you are right that most people on both sides are not thinking about those things right now. They’re just thinking about the present, about survival.

And therefore there is for that reason and for other reasons, there’s been a serious drop-off in the number of Israelis and Palestinians interested in our people-to-people work since October 7th. The hearts have been closed on both sides and the Palestinians are still under to a large degree military closure. They cannot come to joint activities. They can’t leave their towns and villages in many, many cases.

So Roots is continuing but to a smaller degree the people-to-people work. We’re doing curated listening circles at present, and we’ve moved some of the work to other arenas. We’re doing humanitarian work, which is 90% supporting Palestinians who’ve lost their livelihoods. A lot of energy is going there.

We are also doing a lot of intra-communal work, not bringing the two sides together, but simply Israelis separately and Palestinians separately, trying to develop and to to nurture the moral consciousness of the humanity of the side and how we can understand our identities as not being in opposition to the humanity and the identity of the other side. And after the humanitarian work and the intra-communal work, there is the anti-violence work. We work in Palestinian schools to help discourage violence and to head off violence. And even more than work in Palestinian schools, we’re working among Israeli young people, the hilltop youth and and in the outposts and in settlements, working with parents, with rabbis, with teachers, with community leaders and sometimes with the young people themselves in order to discourage violence and to try to head it off when we see it brewing.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the war?

Hanan Schlesinger: Good question. I really don’t know because for many becauses. One of them is that Gaza is unlivable now. In in broad terms, there has to be, I think, a international coalition that the Arab countries have a large say in and part of.

That’s about a an Arab-Palestinian regime in Gaza. That’s about international rebuilding. That’s about diplomatic relationships with Israel and Saudi Arabia, continuation from the Abraham Accords. Of course, part of that is Hamas cannot continue to be, cannot continue to be the ruling party in in Gaza.

And all this seems unlikely today. All this seems unlikely. Uh, certainly, let’s put something on the table, right? At least 50% of Palestinians in Gaza, according to polls, are willing to leave. Had there been a country willing to take them, I, from a moral perspective, cannot say that I’m against them leaving.

But on the other hand, at the same time, in no sense am I, am I am I in favor of any steps on the part of the state of Israel to make them leave or encourage them to leave. That’s their homeland.

Sruli Fruchter: Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum? And do you have any friends on the quote unquote “other side”?

Hanan Schlesinger: Yeah. So, by others, I’m identified as being part of the extreme left and the extreme right at the same time.

Extreme left because I’m in favor, because on a level of sociology, I say that from the river to the sea is all Palestine. Of course, I also say from the river to the sea is all Israel. So those two statements, from the river to the sea is all Palestine and all Israel, that makes me part of the extreme left and the extreme right.

Sruli Fruchter: And where you and where do you identify religiously?

Hanan Schlesinger: So, wait, that’s how other people, others identify me.

Where do I identify myself? I feel much more affinity with the left than the right. Except for the fact that the left doesn’t doesn’t usually accept the deep Jewish connection to the whole land from the river to the sea, right? Including, including Beit El, including Shilo, right, and including Yerushalayim and Efrat and including Chevron. So then you ask, how do I identify religiously? I identify religiously as part of the progressive Orthodoxy.

Sruli Fruchter: And if you’re not comfortable talking about this.

Hanan Schlesinger: But but let me say that I do not limit myself to discourse with uh with Orthodox Jews or progressive Orthodox Jews. I have many, many friends and colleagues who are reform Jews and unaffiliated Jews and who are Christians and who are Muslims, even deeply believing Christians and deeply believing Muslims. You asked if I had connections to people on the other side.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, friends on the other side.

Hanan Schlesinger: Most of my colleagues in in Shorashim and Roots are settlers, right? Who look like settlers. And I have deep connections to them. We work together all the time. And partially we share ideology, partially we don’t.

In my family, there’s all all types. There are those who followed me, there are those who have not followed me. I don’t have any Chareidi friends, although I’m having a meeting with a potential one tomorrow.

Sruli Fruchter: Oh, I hope it goes well.

And if this is too personal, you’re welcome to skip it, but I know that before our interview began, you mentioned that you were living in Alon Shvut and you moved to Yerushalayim, which from our conversation I gleaned is likely because of political reasons related to everything now. How did you come to that decision and has that affected your relationship with others?

Hanan Schlesinger: Has it affected my relationship? Okay, we’ll go back to that. We’ll start with the I don’t call my move political.

Sruli Fruchter: Uh-huh.

Hanan Schlesinger: I call it an ethical political.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: Because it’s not that I left Alon Shvut because I thought that that area should be or will be eventually part of a Palestinian state. Not saying that I agree or disagree, but that’s not the reason.

The reason was ethical political because I began to understand, even more so since the war, that although the settlement movement is based upon the real, legitimate, true Jewish connection to the whole land of Israel from the river to the sea, including Judea and Samaria, the West Bank, and therefore Jews have a deep connection to that land and have a in principle right to live in that land.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: Although that’s all true, at the same time, the way, the fashion in which that connection to the land, Judea and Samaria is being expressed through the settlement movement, incorporates many elements that come at the expense of the Palestinian people.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: The deep expense. Land is being taken, rights are being restricted, livelihoods are being suppressed. And I saw how by living in Alon Shvut, I am part of systematic oppression, and I could no longer stomach that.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

So for our last question…

Hanan Schlesinger: Oh, but then you asked me, how do my colleagues relate to this?

Sruli Fruchter: Oh yeah, has that affected any of your relationships?

Hanan Schlesinger: No. I will say truthfully, but tongue and cheek, that one and perhaps more of my Palestinian colleagues are disappointed that I’m leaving.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: Because although they agree with everything I just said, they say to me, Chanan, by living there, you’re able to influence your neighbors to make the reality better. By living there, you’re five minutes away from me or I’m on the road and I make a phone call, come and help me, and now you’re gone. So there’s some truth in that, but I counter and I say that I basically lost most of my influence among the settler population because my my moral vision has expanded to a point in which we see different realities.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: So I don’t think I’m doing any disservice to the Palestinians by moving and I’m making a statement that’s important for me and I hope maybe important for others.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. Um, do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish people?

Hanan Schlesinger: Fear.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Hanan Schlesinger: I have, and I always will have hope, and I will live my life on the basis of that hope. And I will, and I think I succeed in not letting the fear dictate my actions. But yes, I have deep trepidation for the future of the Jewish people in the land of Israel.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Okay. Well, Chanan, thank you so much for answering our 18 questions. How was this for you?

Hanan Schlesinger: Thank you for helping me to think.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Okay, wonderful. Thank you. Thank you so much. There was so much to unpack in that interview and to continue to dissect and delve into.

And as always, I hope that this is a starting point for your own curiosities, questions.

Hanan Schlesinger: and discussions. Thank you as always to our friends Gilad Brownstein and Josh Weinberg for editing the podcast and video of this respectively. And as always, if you have questions you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, please shoot us an email, info@18Forty.org.

And be sure to subscribe and share with friends so that we can reach new listeners. I am your host Sroly Fruchter and until next time, keep questioning and keep thinking.