Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Sarah Yehudit Schneider discusses 18 questions on Jewish mysticism, including growth through joy and free will.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism. She highlights that traditional Kabbala often focuses on mystical realms associated with the masculine, and in her current work she is actively exploring and articulating the Kabbala of the feminine.

Sarah Yehudit Schneider is the founding director of A Still Small Voice, a correspondence school that provides weekly teachings in Jewish wisdom to subscribers around the world. She is the author of several books, most recently Dark Matters of the Soul: The Kabbala of Shame (2024).

Here, she joins us to answer eighteen questions on Jewish mysticism with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy including growth through joy in the Messianic Era and how to reconcile God’s all-knowingness with free will.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Sarah Yehudit Schneider, it’s such a privilege and pleasure to be with you here in the heart of Jerusalem.

RABBANIT SARAH YEHUDIT SCHNEIDER. Nice to meet you. Well, here as well.

LEVY. And you’re a published writer, you’re the founding director of A Still Small Voice, and you have taught so many people throughout the years. You’re involved in homeopathy, you’re involved in teaching, writing, and so many different things. And today we’re going to speak about Jewish mysticism. So what is Jewish mysticism?

SCHNEIDER. Well, I think Jewish mysticism is not so different from any [type of] mysticism. It’s the striving to build a relationship with the Creator, with Hashem. And to bring one’s life into line – body, heart, mind, and soul – into line with spiritual law.

LEVY. So how were you introduced to it?

SCHNEIDER. Actually, I was introduced by my brother who joined TM, transcendental meditation, and he initiated the whole family into meditation. And that was my introduction. That was about 50 years ago. I’ve been meditating pretty much daily since then, but I quickly moved away from transcendental meditation into meditations of my own design.

LEVY. So how would you advise someone else that wants to connect with Jewish mysticism that’s starting out at the beginning? What path would you direct them to? Any specific books or paths or experiences?

SCHNEIDER. First, I would talk to them and find out what their sensibilities are. Are they more meditation oriented or prayer oriented or intellectually oriented? And then I would suggest books or classes or practices that would speak to them.

LEVY. So in an ideal world, would everyone be mystics?

SCHNEIDER. Well, I think yes. I think that that’s kind of the Messianic striving and [the] model is for everyone to kind of actualize their potential of a relationship with the Divine.

LEVY. Which happens through mysticism.

SCHNEIDER. I think mysticism is the process of actualizing one’s potential relationship with the divine.

LEVY. So when you say the divine, or what people refer to as God or Ein-Sof, all these different terms. What is God?

SCHNEIDER. Right. So in the writing that I do, I kind of work with the pshat in the some sense of the yud, key, vav, key, which is –

LEVY. That’s the simple understanding.

SCHNEIDER. That which was, is and will always be. That which preceded creation permeates creation and will endure beyond its passing. But for myself, my personal connection to Hashem, I experience Hashem as the primal will to good that eternally creates and sustains the universe. And so the feeling that there is a primal will to good that is pushing us along in our journey.

LEVY. Do you imagine that in a tangible way? Is there something that comes to mind when you think about God, or is it more of just a description that’s beyond a specific tangible expression?

SCHNEIDER. Yeah, I kind of am drawn to that description of Hashem, primal will to good, because it’s not concrete. It just is a force that is kind of behind the scenes directing the unfolding of things in a way that is assuredly toward good.

LEVY. And so what’s the purpose of the Jewish people?

SCHNEIDER. The entire creation is a single universe encompassing adam [man]. Like it says when the first adam was created, he spanned from heaven to earth and one end of the world to the other. And the Jewish people are the inner soul core of that universe encompassing adam. The I-center that is charged with the mission of fulfilling the purpose of creation, which from the way I understand it is that divinity before creation, by definition it was lacking nothing except in some mysterious sense, the experience of actualized relationship, because there was no other with whom to relate. So Hashem created creation, i.e. us, to be this other. And to enter into all the myriad-faceted possibilities of relationship, some of which have already happened and some of which, the more consummate levels of which, have yet to be realized. And so that creation is the totality of creation, is really an adam or a Shechina, there’s many ways to reference it.

But that’s the kind of feminine principle that is leshem yichud kudsha berich hu ushechinteh. For the sake of the unification of the Shechina or indwelling face of Hashem and the Holy One, the transcendent face of Hashem. For the unification of the transcendent and the immanent, we – that’s kind of the point of our creation – that’s why we’re here. And the kind of I-center, the inner soul core and identity of the Shechina or adam is the Jewish people that are really kind of making the relationship, directing the unfolding of that relationship.

LEVY. And you mentioned leshem, the special passage that kabbalists often use before they say certain blessings and certain prayers. How does prayer actually work?

SCHNEIDER. I mean, there’s many kinds of prayer. There’s the prayer of praise, the prayer of thanksgiving, and the prayer of request. And the prayer of request is really the mitzva of prayer. And in some sense, people would think it maybe was the lowest, like praise and thanksgiving would seem to be more lofty, but really the essence of prayer, in terms of the mitzva of prayer, is to cry out to Hashem in a time of need.

And most people think of prayer as us trying to convince Hashem to give us something that He’s not necessarily, like, He’s not opposed to giving it to us but He’s not – hasn’t really thought about it yet. But really the challenge of prayer is that Hashem, [over the course of] the creative process, there arose within the mind of God the thought of creation, and a vision of creation’s glorious success and Messianic achievement. And the utter glory of that inspired Hashem to actually create creation altogether.

And so the challenge of prayer is not to convince Hashem to give us something that he is neutral about, but to want our – in that vision that arose in the creative process, it included the entirety of creation and every single individual in it. And so our work is to – the challenge is not to convince Hashem of anything but to want the perfection of our soul and the success of our mission individually and collectively as much as Hashem wants to bestow it. And the prayer that we speak and the vision behind it or the content of it becomes the vessel, or keli as it were, that pulls down the lights that are exactly configured to fill that space, that lack. And that lack is – and to the extent that that lack is on point in the sense that it really does express what our soul is designed to do, Hashem is pleased to answer that prayer. He’s been waiting for us to ask for it and to realize that that is kind of where we’re headed and what we’re designed for.

LEVY. And then what’s the goal of Torah study?

SCHNEIDER. The goal of Torah study is to kind of, I think, hardwire our consciousness into alignment with the deeper truths of the universe. And there’s a transformation that happens in Torah study. As our sense of the world and reality corrects itself, the way [we interpret] the moments of our life and the challenges of our life corrects itself. And we, and our life, slowly or hopefully even sometimes instantaneously comes into line with spiritual law and Hashem’s will for us.

LEVY. Amazing. Do the mystical sources view women and men as the same?

SCHNEIDER. No. There are, I mean, they’re 95, 98% the same, but there are also many differences, I mean, in terms of our humanity we’re the same, but in terms of our gender, there are differences. And I mean, the most basic one then is the mashpia and mushpa, the bestower and the recipient. But that has all kinds of secondary repercussions.

LEVY. So you talked about two different capacities of feminine and masculine in terms of bestowing and being bestowed upon. What does that mean in the context of the masculine and the feminine?

SCHNEIDER. It’s actually – I’m working right now on a exploration of, the Ari, Rabbi Isaac ben Solomon Ashkenazi Luria, says in a number of places in his writings that he is only giving over the teachings, the kabbalistic teachings of the realms of yosher, of the hierarchical realms, which is associated with the masculine, and he’s not really giving over the teachings that are related to the the worlds of igulim, the circle worlds, which are associated with the more feminine modality.

And so I understand that as a kind of invitation for women to articulate the Kabbala of the feminine. That the classic Kabbala is really very much masculine oriented and doesn’t so much deal with the feminine experience. And so in the teaching that I’m doing right now, I’m really exploring what the Kabbala of the feminine is. And kind of starting with a premise that the Kabbala of the feminine kind of presents – begins from below to above, whereas the Kabbala of the masculine generally moves from above to below.

And the above to below is really what’s called the seder hishtalshelut, the unfolding of light into matter, and it’s a very kind of technical and detailed Kabbala. And the Kabbala of the feminine, as I’m understanding it, is that it begins with something kind of concrete, an issue or problem or question that is concrete below, and then looks to classic Kabbala for the paradigms. There are many paradigms that apply to different kinds of situations. So to find the paradigm from classic Kabbala or masculine Kabbala that sheds light on and helps to unpack the issues on how to work with this particular matter.

And so I just published a book called Dark Matters of the Soul: The Kabbala of Shame. And so I’m working with the issue of shame in a manner of Kabbala of the feminine, and it’s exciting and interesting.

LEVY. Well, I’m very excited because that means that in the generation we live in, there’s a female view of Kabbala, because traditionally, as we’ve seen in all the literature, there was a dominance of masculine teaching just because of the way society was. And now you’re saying that even the Ari, who was one of the greatest proponents of kabbalistic thought, acknowledged that. And so now there’s a new way of thinking about this.

Can you give just a short example? I know it’s hard to say because you’re an expert in this now, what is the feminine kabbalistic view of shame, for example? How is it unique? What does this female Kabbala approach look like?

SCHNEIDER. Well, it’s not so much like a feminine –

LEVY. Masculine.

SCHNEIDER. Yeah, the issue of shame itself, but how to work with shame is what I’m exploring now in terms of as a Kabbala of the feminine. But it’s kind of a complicated thing to explain.

LEVY. So I guess our viewers are going to have to read your book.

SCHNEIDER. Yeah. But I just want to say that the Ari also, if you want to find out what the Ari has to say about the feminine, you look into the chapter called “Mi’ut Hayareach,” the diminishing of the moon. And there he gives over a seven-stage process of feminine development that applies to the feminine on all scales, from the inner feminine, to the feminine in a couple, to the entirety of creation is feminine in relation to Hakadosh Baruch Hu [God]. And the feminine life cycle as it moves through these seven stages, it moves from diminishment into fullness of stature. And the messianic ideal of the masculine and feminine as presented by the Ari is where he and she meet panim bepanim shaveh legamrei, face to face and completely equal. And when I first came across that teaching, I couldn’t believe it. I mean, it seemed like it was a feminist treatise that the Ari was presenting there of like a relationship of absolute equals that –

LEVY. Well it’s ultimately coming to the kabbalistic view of true unity.

SCHNEIDER. Right. Exactly.

LEVY. And growing back to that real primordial unity that really created the universe as we know it today.

SCHNEIDER. Yes, yes, exactly.

LEVY. So, applying that today, what is the main impediment or what is the main thing that’s stopping people from living a more spiritual life?

SCHNEIDER. Well, I think that it’s because it starts out very abstract. It’s called Pnimiyut HaTorah [the innermost reality of the Torah] because it’s very deep and it’s hard to get a handle on it or to really concretize it. You’re not really supposed to concretize what’s happening there. So I think for people it’s hard to know to trust themselves and to know how to really enter into that level of spiritual experience.

LEVY. So it’s a certain awareness. How do we rectify that? How do we help people connect to their deeper spiritual essence?

SCHNEIDER. Right. I mean, I think that meditation is really the entry. I don’t know, I mean, for me that was the entryway, to dedicate a certain amount of time each day. I mean now it’s been over fifty years of just sitting and listening in and you begin to become more familiar with the landscape, so to speak, the inner landscape of the Pnimiyut layer of oneself.

LEVY. So if someone’s never done that, what is Jewish meditation?

SCHNEIDER. So meditation is a continuous flow of thought on a particular object or point of focus. So you pick something as your focus, and then you kind of sit with it and try to hold your attention there, which you can never do, and you wander and you come back and wander and you come back.

And so really, if meditation is a continuous flow of thought on a particular object or point of focus, then you choose a point of focus that has Jewish content to it, and it becomes Jewish meditation. And that can be a name of Hashem or a verse or tefilah [prayer] or learning. You can and should experiment with praying meditatively or learning or studying meditatively. And then also if there’s some prayer in your heart that you want some help with or guidance about, you can kind of find a pasuk [verse] that expresses that and make that your kind of meditative focus.

LEVY. And why did God create the world?

SCHNEIDER. Well that’s what I said earlier, that Hashem before creation, by definition, was lacking nothing except in some mysterious sense, the experience of actualized relationship, because there was no other with whom to relate.

LEVY. And does that mean that God, Who is infinite, was lacking something? How do we relate to that?

SCHNEIDER. Right, [God] was lacking nothing except in some mysterious sense, the experience of actualized relationship because there was no other. It just wasn’t another.

LEVY. So God [made us to become] that receptacle [in order to create] that opportunity to be able to fill that.

SCHNEIDER. Right – which is really just divinity, the transcendent and immanent faces of divinity reuniting in their oneness is what is happening. The immanent expression of divinity is the other, so to speak.

LEVY. So then how God used His will to be able to create that. Did God endow us with free will? And if so, how does that relate to God knowing everything?

SCHNEIDER. Yes, a relationship, in order for it to be a real relationship, it requires that the other have real autonomy, and autonomy is basically defined as free choice. So the teaching is, in the same way, how to reconcile Hashem’s all-knowingness with free choice? And this is the teaching from the Or HaChaim: He says that in the same way that Hashem withdrew His all-presence in order to create the possibility of our physical existence, so Hashem withdrew and constrained His all-knowingness in order to create the space for our free choice. Just like Hashem in any moment could fill the the space, the tzimtzum, the womb of vacant space that holds the creation, there’s nothing preventing Hashem from shining His light back in there as it was before the creative effort. But more than Hashem wants to shine His light back into that space, he wants us to exist as an other in order to experience the actualized relationship.

So the same way with His all-knowingness, even though Hashem could know whatever is going to happen before it happens, more than Hashem wants to know that, He wants to create the space and possibility of our free choice. So Hashem constrains and conceals his all-knowingness. Metaphorically, He doesn’t look in order to create because knowing, daat, has a compelling aspect to it. It means to know something so deeply that your instinctive and reflexive response to the world is now conditioned by that information, by that knowing.

So Hashem knowing would be causal. It would force us to choose in accordance with His preconception. So more than Hashem wants to know what’s going to happen before it happens, Hashem wants us to have authentic free choice, and so He constrains His all-knowingness in order to create that possibility.

LEVY. Wow. So we’re meant to use that free choice to do the right thing, obviously.

SCHNEIDER. Yes.

LEVY. That’s the desire.

SCHNEIDER. Right.

LEVY. Us doing the right thing ultimately takes us towards the end of days, so to speak, this time of Mashiach, this messianic redemption. When I say Mashiach, what comes to mind? What does Mashiach mean?

SCHNEIDER. Growth through joy.

LEVY. Can you say that again?

SCHNEIDER. Growth through joy. As opposed to –

LEVY. I’m gonna have to ask you to unpack that a little bit.

SCHNEIDER. As opposed to growth through blood, sweat, and tears. Now, growth is a lot of work and there’s a lot of suffering in the world. I mean, just horrendous suffering in the world. And it is a force of growth. We learn how to make the best of it. And –

LEVY. So in the Messianic era, we will be growing through joy.

SCHNEIDER. Right.

LEVY. We’ll be able to see –

SCHNEIDER. We’ll still be growing, but we’ll be growing through joy.

LEVY. So it won’t be hazor’im bedim’a, we won’t be sowing seeds through tears but through joy.

SCHNEIDER. Right.

LEVY. And where does the State of Israel fit within this? Is this stage in the process of redemption?

SCHNEIDER. It seems like that to me. I mean, it seems like an amazing accomplishment and gift of the Jewish people to be able to plant ourselves here in our holy, promised land.

LEVY. And how do you see that? I mean, you live in the Old City. How long have you lived in the Old City for?

SCHNEIDER. Probably about thirty-five, forty years, something like that.

LEVY. Wow. And how do you see the State of Israel as an expression of a process towards bringing about the redemption?

SCHNEIDER. Well, there are all kinds of esoteric things about that, but really it’s just as an attractor of the Jewish people and the beginning of us having to figure out how to love each other and work with each other and build a new world together.

LEVY. So in this new world together, even beyond us, what is the greatest challenge facing the world today?

SCHNEIDER. In the world today? Boy, so many challenges. I don’t know what the greatest challenge is. I guess sinat chinam is the greatest challenge.

LEVY. Baseless hatred.

SCHNEIDER. Yeah. And I do think that that is part of the reason I wrote the book about the Kabbala of shame. Because we’re not going to solve the problem of causeless hatred until we become aware of how shame circulates in our psyche and is ultimately the cause of our causeless hatred.

LEVY. And so how has modernity changed Jewish mysticism?

SCHNEIDER. Certainly the texts that are the basis of and the guides of Jewish practices and mystical practices are so much more available now than they have ever been, and the average person is literate enough to be able to work with those texts and to find their way through them. So I think that’s probably the biggest change.

LEVY. And in terms of mysticism as a whole, is the Jewish brand of mysticism different to other traditions, cultures, religions, and views of mysticism? What makes Jewish mysticism unique?

SCHNEIDER. Well, I think Jewish mysticism, because it’s very much a family-based religion and practice, I think it becomes more an embodied mysticism. I mean, even though meditation is a part of it for sure, it’s really very much about bringing Hashem into the day-to-dayness of life and to access the soul level of things even in the chaos of daily life.

LEVY. So does one need to be religious to study Jewish mysticism?

SCHNEIDER. Well, it helps. But I don’t think you can really access the deepest, deepest levels of it outside of a mitzva practice because so much happens inside the mitzva in Jewish mysticism. But you can certainly make headway and you can certainly grow. There are resources and tools that are available whether you’re religious or whether you’re not religious that will kind of take you somewhere. But I do think that the fullness of the practice is very much mitzva centered.

LEVY. Can mysticism be dangerous?

SCHNEIDER. I think that our our awareness of the world and science has expanded our consciousness to such a degree that we that we’re not so vulnerable to kind of melting down or whatever it was, going crazy, that would at least reportedly happen when people delved into teachings that were too deep for them. But I don’t see that as a problem for us. I think our consciousness is expanded to a degree that –

LEVY. As humanity, as –

SCHNEIDER. Yeah, yeah. As humanity, we’re not so vulnerable.

LEVY. And you talked about one of the unique factors and features of Jewish mysticism is bringing it into the family, bringing it down in a practical way. Personally, in your relationships, is there a place where we see it expressed? Can you give an example of where Jewish mysticism has actually influenced how you relate to yourself or others?

SCHNEIDER. Well, it’s profound. I mean, everything has changed as a result of Jewish mysticism. I can’t think of a specific example

LEVY. With a child, grandchild, student.

SCHNEIDER. Uh-huh.

LEVY. Does it find expression in the day-to-day relationships?

SCHNEIDER. Certainly how I interpret the situation and what the relationship is calling for is very much informed by my understanding of the world based on a more mystical or kabbalistic model of things. But I can’t think of a specific –

LEVY. I think that’s a good sign because it pervades everything. We’ve talked a lot about me asking you questions about the thought. I’d love you to share one thought. What is one Jewish teaching, a mystical teaching that inspires, animates, inspires you in terms of right now that comes to mind or in general?

SCHNEIDER. Well, I guess one of the things that I’m teaching a lot about now is the relationship of prophecy to ruach hakodesh. That generally –

LEVY. Ruach hakodesh is divine intervention?

SCHNEIDER. Yeah, inspired intuition. And generally prophecy is considered the kind of higher channel of transmission between a person and the divine, and ruach hakodesh is something lower; it is secondary. But in prophecy, the prophet’s ego and personality just goes underground. It’s the extent to which the authority of the prophecy depends upon the absence of the prophet’s impact on that transmission. The term is called an aspaklaria hameira. They should be a transparent lens and have no impact on the transmission that Hashem is sending through them. And so prophecy is more of a master and servant, whereas ruach hakodesh is very much a shared kind of reverie of creativity. It’s more of a partnership between the person and Hashem, where the person initiates the process, has some kind of issue or need or question, and they invest effort into trying to solve it. And that effort on their part creates the keli that pulls down the providential assistance or guidance from Hashem. And in ruach hakodesh, even though there is prophecy because the prophet can say ko amar Hashem, thus spoke God, prophecy is more authoritative, like it has a less of a margin of error than ruach hakodesh where Hashem is expressing Itself through the thoughts in your own head, but you understand that those thoughts are actually not your own, they’re actually Hashem’s.

And so in ruach hakodesh there is an intimacy of the relationship of sharing – the things are close when they’re similar and distant when they’re different. And so the connection between the person and Hashem, they’re sharing this effort of trying to solve this problem together and working together, and the prophet’s personality, unlike in prophecy, is active and involved and is very much participating in it and kind of setting the tone of the ruach hakodesh effort that’s happening. And so in that sense, if the purpose of creation is actualizing the potential of relationship, then that happens in a consummate way in ruach hakodesh because both Hashem and the person are very much active and involved and participating.

LEVY. Beautiful. Well, I feel throughout this conversation a real synchronicity of Hashem and your personality coming through. And you’re clearly steeped in this tradition. You learn, you teach, you write, and you live. So thank you for all you do, really for all of humanity, and we look forward to seeing you continue to inspire so many.

SCHNEIDER. Thank you so much. Really, it’s been a pleasure to speak with you.

LEVY. Same here. Thank you.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Dr. Ora Wiskind: How do you Read a Mystical Text?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Dr. Ora Wiskind, professor and author, to discuss her life journey, both as a Jew and as an academic, and her attitude towards mysticism.

podcast

Yehoshua Pfeffer: ‘The army is not ready for real Haredi participation’

Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer answers 18 questions on Israel, including the Haredi draft, Israel as a religious state, Messianism, and so much more.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

Rachel Yehuda: Intergenerational Trauma and Healing

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we pivot to Intergenerational Divergence by talking to Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, about intergenerational trauma and intergenerational resilience.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

AI & Halacha: On Transparency and Accountability

Rabbi Gil Student speaks with Rabbi Aryeh Klapper and Sofer.ai CEO Zach Fish about how AI is reshaping questions of Jewish practice.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

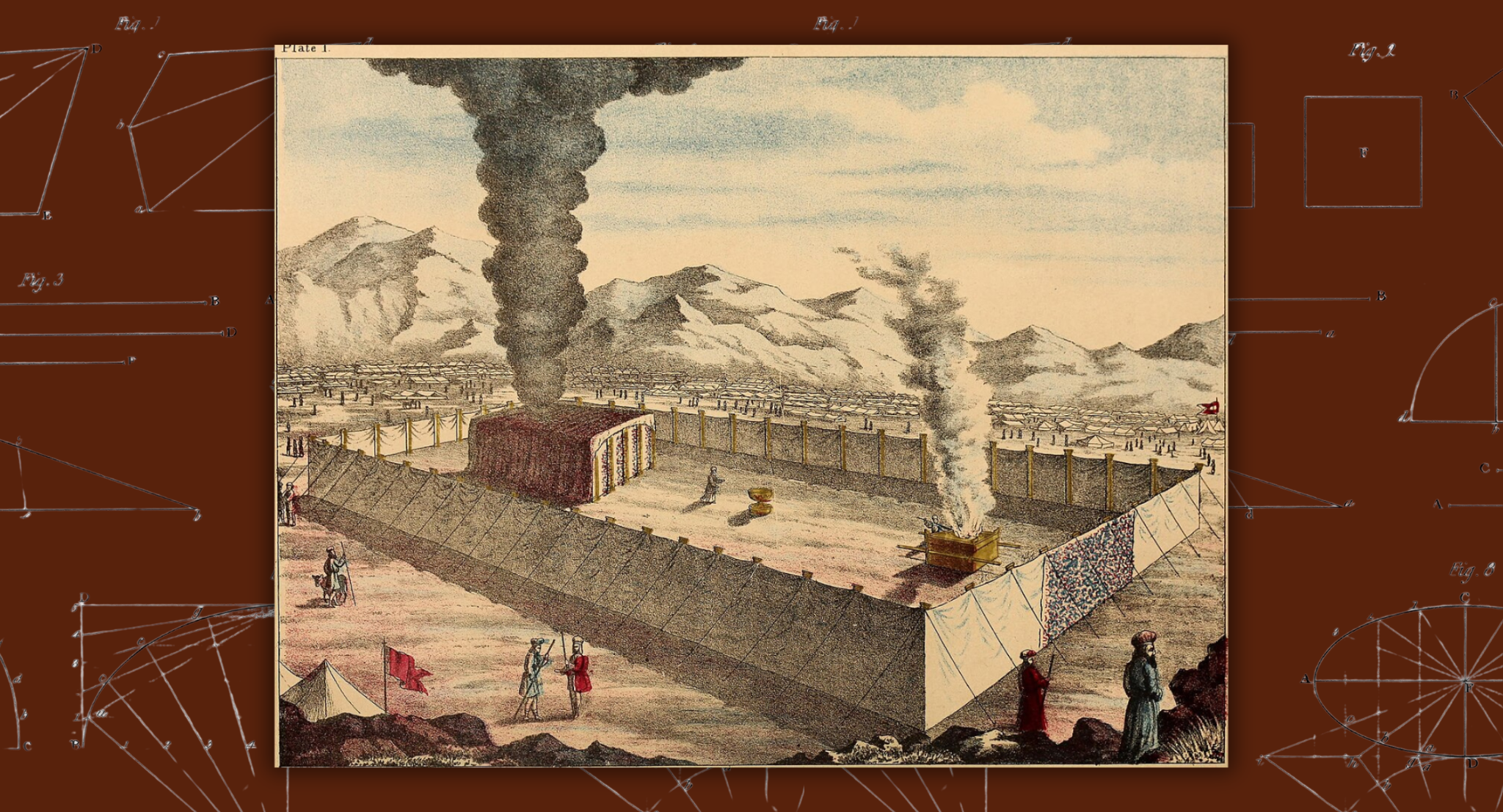

Essays

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

A Letter to Those Going Through Divorce—and Everyone Else

I’ve seen firsthand the fallout and collateral damage of the worst divorce cases–and that’s why I’m sharing methods for how we can…

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

The History of Halacha, from the Torah to Today

Missing from Tanach—the Jewish People’s origin story—is one of the central aspects of Jewish life: the observance of halacha. Why?

Essays

We Are Not a ‘Crisis’: Changing the Singlehood Narrative

After years of unsolicited advice, I now share some in return.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

AI Has No Soul—So Why Did I Bare Mine?

What began as a half-hour experiment with ChatGPT turned into an unexpected confrontation with my own humanity.

Essays

How Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe Saw the Jewish People

What if the deepest encounter with God is found not in texts, but in a people? Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe…

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

We Asked Jews About AI. Here’s What They Said.

This series, recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit, is sponsored by American Security Foundation.

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel, head of a campus Chabad and…