Shais Taub: ‘God gave us an ego to protect us’

Rabbi Shais Taub discusses how mysticism can revive the Jewish People.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

Rabbi Shais Taub’s study of mysticism began with a deep dive into the book of Tanya. Now, he believes that mysticism serves as a practical guide for everyday life, one founded in spiritual principles.

Rabbi Shais Taub is a renowned teacher and noted speaker in the field of addiction recovery. He is the author of God of Our Understanding: Jewish Spirituality and Recovery from Addiction and the creator of “The Map of Tanya.”

Now, he joins us to answer eighteen questions with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy on Jewish mysticism including how it can revive the Jewish People, the perfectibility of the physical world, and seeing children as souls.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Rabbi Shais Taub, [you are] one of the most incredible speakers across the world for decades. Over 10 million views a month through social media and growing dramatically. Thank you so much for being with us here today.

RABBI SHAIS TAUB. My pleasure, thank you so much for having me.

LEVY. So Rabbi Taub, one of the profound things that you do is that you teach mysticism. But what is Jewish mysticism?

TAUB. What is Jewish mysticism? That’s a good question. Because the word mysticism implies something that’s removed, something that’s hidden, something that’s inaccessible. And the truth is that – I’ll use the term Pnimiyut HaTorah, the inner dimensions of the Torah are actually meant not to obscure but to clarify. And not just to clarify in a conceptual way but in a very practical way. Especially the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov, which we refer to as Chasidut – they are meant to be extremely personal, relatable, actionable. So, to answer your question, what is Jewish mysticism? It’s a practical guide for day-to-day life based on spiritual principles. But the emphasis is on how we live our lives.

LEVY. So if the word mysticism sounds like [it is] inaccessible and [meant] to draw us away, you’re saying it’s something that’s there to bring us in. Why does that paradox exist?

TAUB. Well, sometimes you have to maybe back away and get a big picture view before you zoom in. Kabbala, Chasidut [Hasidism], what they do is give us an expanded view of reality rather than just a strictly materialistic view where we’re looking at, very myopically, just at the physical world. It gives us a zoomed-out view, not just that there is a spiritual dimension, but levels of spiritual dimensions, worlds, olamot. But what’s the purpose of that? All of that is to give us context for the here and now. So yeah, in one way, we draw away from the physical world, but that’s part of the process. If it ends there we haven’t really accomplished what it’s meant to do. It needs to bring us back here to this place, at this time, that Hashem is creating something from nothing at this very moment, so that we can see the infinity right here, which is usually some act. I shouldn’t say usually. It is always some type of act. A soul in a body is here to do something, to take action. It could be a word that’s spoken, it could be a physical act, but it’s some type of action that we need to take in this space, at this time, with the person sitting across from us. So we learn all these big things, these lofty things, but then in the end it’s right here, it’s right now.

LEVY. So that’s what we’re doing, and that’s your life purpose, and you’ve made it your life work –

TAUB. Yeah, yeah.

LEVY. So how were you introduced to this?

TAUB. Oh, that’s a great question. I was always sort of aware of the deeper, let’s call them, well we’re using the word mystical teachings, of the Torah, but I didn’t really deeply study, properly study until I was in my early twenties. And I’ll tell you what actually happened. I was introduced to the book of Tanya, and I thought that everybody understood Tanya right when they opened it up and it made sense to everybody, and I had an inferiority complex. So I thought everybody understood it. Which was – it was lucky that I had that misunderstanding.

LEVY. The Tanya being the classic Chabad book written by the Alter Rebbe [Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi].

TAUB. Right, one of the students of the Maggid, who was one of the students of the Baal Shem Tov, and in many ways the Tanya is a codification of the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov. In many ways you could say it’s the most basic text of Hasidic teachings. So I devoted myself to understanding that book really, really thoroughly. Actually, the first project I worked on is called “The Map of Tanya,” where I literally mapped out the chapters of Tanya with color coding and little icons so that I wouldn’t get lost because I thought everybody could just open the book and understand it and find their way around it. And that was really my beginning – immersing myself into Tanya, getting that book clear, at least the structure of it. The book is so rich and dense, it’s not a book that anyone can master. But at least the structure of it, that became very, very clear in my mind. And then I guess that created a file folder system for everything else and then I started importing it into that.

LEVY. So actually through bringing clarity for yourself to this deep text.

TAUB. Yeah, exactly. It was a very personal thing.

LEVY. Was there something that drove you to do that in your twenties? Meaning, growing up Chabad, it’s something that people say and learn. Was there a moment that brought you into that to devote yourself like that?

TAUB. I really came to a point where I thought that it would help me to understand life on a personal level. I didn’t do it because it was holy. I didn’t do it because of intellectual curiosity. I really did it from a from a very practical place of: maybe this will help me figure out –

LEVY. Life.

TAUB. Yeah.

LEVY. So if it does that and it helps you figure out life, should all Jews be mystics? Should they all be learning these works?

TAUB. Well, I think everybody should have a system for understanding life. I think the system of Pnimiyut HaTorah [the inner dimensions of the Torah] is a very good one. I would highly recommend it to everyone without reservation. I don’t know why I paused for so long. Yes. Yes.

LEVY. What do you think of when you think of God?

TAUB. What do I think of when I think of God? Wow.

LEVY. Because that word means so many different things to different people. But what is it to you?

TAUB. Reality. Absolute reality. Maimonides says that everything else exists only because of His existence, but His existence is not dependent upon the existence of anything else. So when I think of God, I think of that that must exist.1 That even in theory, there’s no concept of God not existing. Everything else in theory could not exist. The world doesn’t have to be here. I don’t have to be here. So yeah, I think of absolute reality.

LEVY. Wow. And so what about the Jewish People? What’s our purpose?

TAUB. Wow. You’re going very deep. We skipped all the small talk. How’s the weather? Did you see the game last night?

The Jewish People, our purpose is to represent absolute existence.2 Meaning God. And one of the ways that we do that, by the way, is just in our existence as an eternal people. Just the fact that the Jewish People still exist is a miracle, which is a testimony to the eternality of God Himself. Which is sort of mind-blowing if you think about Jewish identity in those terms, that before a Jew even starts to do a mitzvah, just the fact that a Jew walks this earth and draws breath is a testimony to the eternality of God. Amazing concept.

LEVY. Wow. And how does prayer work?

TAUB. Prayer is our reaching upward.3 You know, we can contrast Torah study with prayer, which are two main modes of our relationship with Hashem. Torah is where the infinite bestows his wisdom upon us in relatable terms. So that’s from above to below. Prayer is where, within the framework of the terms that I’m familiar with, meaning whatever it is I’m going through in my life, the things that I feel I need, that I’m struggling with, from that context, I’m reaching out to God and connecting with Him about those things. So it’s basically like, Torah study is God reaching down to us, prayer is us reaching up to Him. And we need both of those directions to have a dynamic relationship.

LEVY. So then if prayer is us reaching up to him and Torah study is him reaching down to us, what is the actual goal of Torah study for us? Is it to create that access for him to reach down? Or are there other components to it?

TAUB. You know, Torah study is an interesting thing, and in a lot of ways it gets a bad rap because it’s misunderstood. Sometimes when people are trying to, maybe even, scoff at Talmudic hair splitting, they talk about all these theoretical scenarios that would never happen and it’s just so impractical. And what people don’t realize is this. And I got this from Tanya, by the way, chapter five of Tanya. What the Torah describes, and by Torah I don’t just mean the five books of Moses, I mean the entire body of Jewish teachings because everything ultimately is an amplification and an unpacking of the text of the five books. When the Torah describes a scenario and tells us what the ruling should be, the halachic ruling, the legal ruling. Even if that scenario would never come to pass, even if it would never really transpire, the fact that the infinite one has an opinion about what the ruling should be if it were to happen, what that means is that when I learn that opinion and I make it my perspective, I’ve aligned my finite mind with his infinite mind so that I’m now seeing something in this world in a way that God Himself sees it.

LEVY. And that’s actually refining your mind [through] that process.

TAUB. Elevating my mind, refining my mind, which is also a very important concept. This is also from chapter five of Tanya, that Torah study is compared to food. King David in Psalms actually says vitoratcha betoch meoi,4 which means your Torah is in my stomach. What Torah is in your stomach? It should be in your brain. Why is it your stomach? So he explains that just like when you eat food and you metabolize the food and then it becomes part of your flesh and blood, when you learn Torah it becomes part of the wiring of your brain. So Torah study is not just about the moment that you’re spending in the activity of studying, it’s actually about how your brain is affected after that minute is over. That now, having learned what you learned, which is how to look at something of this world not as just another created being within creation looking at other created beings but being able to get up there and look at the creation from the perspective of creator, that changes your brain, changes the way you experience and process reality. So, yeah, it’s not just knowing this information, it’s that it changes the way your brain functions, which is ultimately the point of it, the transformational aspect.

LEVY. It’s like with physical activity, you build muscle memory. This is almost like soul memory. It’s interesting: Rabbi Chaim Volozhin talks about sort of daat Torah:5 someone that is able to bring a Torah perspective because they’ve imbibed and ingested it and therefore become so much of it that there’s a certain perspective they can represent through it.

TAUB. Right, where somebody who has really sufficiently absorbed a Torah perspective can have a Torah opinion about a matter that he has not explicitly studied. In other words, it’s not just that he knows all the scenarios that have been discussed and he knows the answers and he can quote the answers. It’s much more than that. His brain now functions as a Torah brain, and even in a new scenario that was never explicitly discussed, he can figure out the Torah perspective.

LEVY. Lehavdil [excuse the comparison], we see it with AI in the sense that it’s able to compute and import all these things. Obviously it doesn’t have the same level. So why not a human being who does have a soul on a deeper level that can do that in an even deeper way?

TAUB. Yeah, if artificial intelligence can do it then why not natural intelligence? How much more so? Exactly.

LEVY. So what about men and women? Does mysticism view them as the same?

TAUB. Different, obviously. I shouldn’t say obviously, I shouldn’t take anything for granted. But the differences between men and women are primarily spiritual differences. And the other differences that stem from that, biological differences, social differences, those are all an expression of the spiritual differences. And really, we think about men and women in human terms. The truth is from a perspective of mysticism, primarily male and female are archetypes within God Himself or Herself. I mean, there’s masculine and feminine within God. Obviously the infinite one cannot be nailed down to any one description, but we’re talking about different modes of expression, how the infinite one expresses different aspects of self to the finite world.

So there are masculine modes of expression on God’s part, there are feminine modes of expression, and those archetypes are the root of masculinity and femininity. Where were you going with this? Because I think there’s –

LEVY. No, I just wanted to understand because as you said, some people take it for granted and some people can’t. But I think the framing that you said of a masculine and feminine as opposed to men and women, and therefore it can be expressed through men and women in different ways is –

TAUB. There are so many examples of masculine and feminine that have nothing to do with gender. As you know, because that’s where it becomes, I think, at least in today’s day and age, where we start to lose the plot a little bit. For instance, when I’m speaking about marriage, let’s say, and I have to explain masculine and feminine paradigms. Before I’ll even talk about, you know, differences between men and women type stuff, I’ll talk about the difference between the six work days and Shabbat. Right? Because six work days are masculine. Shabbat is feminine.6 She’s the queen. And I’ll explain the difference – that during the six work days you go out and you do. It’s all about doing. And Shabbat is a cessation of doing, but it’s not passive, it’s actually being, it’s something deeper, it’s essence. And when you understand the relationship, how for instance the six work days relate to Shabbat: You go out, you work, you buy the food, you prepare the food, but then Shabbat is when you serve the food and then you take a kugel that you made on Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday, and you eat that on Shabbat. And it is no longer just a kugel, it becomes a whole spiritual experience that gives you the koach, that gives you the energy to go out and have meaning to do it all over again. So there’s this relationship between these two energies.

LEVY. It’s the mekor habracha,7 the source of blessing. But I think the power of that is that you’re almost depoliticizing and you’re actually moving onto a different concept [in order] to say that weekdays and Shabbat can have these paradigms. Therefore a paradigm or a concept is not necessarily – and therefore we’re not trying to offend a male by saying that they’re like a weekday –

TAUB. Right.

LEVY. But we’re trying to say that there’s a certain energy. And what’s interesting is biologically, we all have masculine and feminine attributes even if we are a masculine entity, from a gender perspective, or a feminine entity. So –

TAUB. Yeah. I think that’s also an important concept that these things are much more nuanced than perhaps when you take a sort of simplified or oversimplified approach, so you think we’re talking about either-or, black-and-white, and the the more you learn Pnimiyut HaTorah, the inner dimensions of the Torah, the more you see that there are so many nuances, there are so many shades and degrees, and things are much more complex. They’re not reality; reality is complex. But, there’s a system for understanding that complexity.

LEVY. So that system sort of guides us towards a spiritual life. But what is the biggest obstacle to living a more spiritual life?

TAUB. Fear. Fear is the God-given survival impulse of the ego gone awry, over exceeding its functionality. God gave us an ego to protect us, to keep us safe, but it over performs, it just becomes too good at its job until it becomes counterproductive. So, the antidote is letting go, surrendering.

LEVY. Surrendering is the antidote to fear?

TAUB. Yeah, because the fear is control or the attempt to control, which is the blockage between true spiritual consciousness, awareness, and then the surrender is the letting go of that, that attempt to control. The term we use in in Hasidism is bittul –

LEVY. Bittul, yeah.

TAUB. Which is often is translated –

LEVY. Nullification or?

TAUB. Nullification, yeah, which sounds kind of weird, like what’s nullification? But really –

LEVY. It’s more of a letting go. That’s what you’re saying.

TAUB. It’s letting go. It’s the surrender. It’s the graceful acceptance of what is. And like I was saying before, what is God? God is absolute reality. So bittul, nullification doesn’t mean nothingness, it’s the exact opposite. It means letting go and allowing everything to be as it is, to be manifest and for the person to be present with reality.

LEVY. So this world is a pretty tough place to do all the things you’re doing. Why did God create the world?

TAUB. The Midrash Tanchuma8 says that Hashem created the world because, and it uses a really interesting word: nitaveh [desired]. Hashem had a taava, you could translate taava as a desire, a craving, you could even translate it as a lust to have a dira betachtonim, a dwelling place in the lower realms. So before we even talk about [creating the world], what is a dwelling place in the lower realms? What’s a dwelling place? What’s a lower realm? What’s a desire? What does desire mean? So there’s an expression, this is from the Alter Rebbe, the Baal HaTanya, the author of the Tanya. He says regarding a taava, regarding a desire, you can’t ask a question.9 What does that mean? I didn’t understand that expression for so long. I used to think it meant if somebody has a desire, it’s not polite. Don’t ask them about it, it’s personal. That is not what it means; it doesn’t mean don’t ask. It means you can’t ask or it’s useless to ask because it’s not rational. Like if somebody makes an argument that they purport to be logical, you could ask them to defend it, explain that to me. And if they can’t, then maybe it’s not as logical as they thought it was. But if somebody says I have a desire and you say, well, defend that, prove that to me. I can’t. I just desire it. That’s just what I want.

LEVY. And it’s also so personal, like someone loves flowers, but I don’t. I can’t understand. But I can understand the fact that they have that desire.

TAUB. Correct, right. It doesn’t have to be my desire, but I understand that. You know, we talk about marriage with spouses a lot. It’s like, I don’t get why that’s something you desire, but I get that that is what you desire.

LEVY. Right.

TAUB. So we speak about Hashem having a desire. Obviously not a practical need, He’s not lacking anything in the conventional sense, but a desire. And it’s a desire that’s coming from the infinite one, so it’s this infinite desire. So it’s an interesting concept. Like you say, why did God make the world? Existence itself is a product of divine desire. Which is why the Kabbalists use romantic imagery, erotic imagery. I mean originally it’s with King Solomon, with the Song of Songs, which was the original metaphor for this. But the Kabbalists expand upon this much more [using] the aforementioned masculine and feminine paradigms that we were discussing. Why do they use so much of this marital, intimate imagery to describe creation? Because ultimately creation is an endeavor of this –

LEVY. Visceral desire of God.

TAUB. Yeah, this passion, this –

LEVY. It’s almost like, you know how you love that food, or you know how you love that person, or you know how you love that thing, then that’s the channel. You don’t know what it is, but that’s the channel.

TAUB. Right. But the difference is, see, we as humans have desires and sometimes our desires are a function of our weakness because we don’t desire things that are necessarily worthy of desire all the time. What does it mean though that Hashem has a desire? So I was saying earlier, actually I guess this is how we started, you said how do I define God? I said absolute existence. So think about it like this. If I have a desire, I don’t necessarily have to get my desire fulfilled. In fact, there probably are a lot of desires I have that would be better off if I were not to pursue them, right? But Hashem is absolute existence. He must exist. There’s no such thing as Him not existing. And so too, it follows, if He has a desire, He must fulfill that desire. There’s no such thing as Him not getting that desire fulfilled. So if He wants a world so that this can be – now what does it mean a dwelling place in the lower realms? A home. That He wants His home not to be in heaven, in the angelic realms, but here in the physical world where we struggle and where we have free choice and where we have distractions and temptations. And this is the place where He ultimately wants to be revealed. So He has to get it and He will get it. And that’s what we call Mashiach. That’s the perfection of this world.

LEVY. So where do we fit in this in terms of free choice? Does free choice exist?

TAUB. For sure. Obviously. Yes, yes, yes, yes. Free choice exists because we have to make a decision whether or not to be part of this. Hashem is going to get His way. Mashiach [the Messianic Era] is coming. But the question is, do we want to be part of it? And it’s not a binary question, yes or no. It’s [a question of] to what extent do we want to be part of it? Do we want to devote ourselves to this entirely? Do we want to do it as a hobby, here and there, when I’ve got time? Or do we want to throw ourselves into this as intensely as we can to mirror Hashem’s intense desire, what you call the visceral desire, which I like that word. Yeah –

LEVY. It’s like the conversation between Mordechai and Esther. The train’s going. Are you going to be part of it or not?

TAUB. Yeah, that’s right.

LEVY. Im hacharesh tacharishi [if you remain silent].10

So you alluded in both of the last two questions to this Messianic Era, Mashiach. What is Mashiach?

TAUB. Mashiach is the perfection of the physical world. In the most simple sense, it’s a time of peace and a time of bounty in the most practical sense. But it’s more than that as well. It’s the revelation of the infinite within the finite. It’s the ultimate expression of Godliness because for the infinite to be expressed within the infinite, what’s the big deal, right? It’s the infinite expressed within the finite. So what happens is that the physical plane becomes the ultimate expression of Hashem’s absolute reality – to the extent that the physical plane becomes more elevated than any of the heavens, which is a very hard concept to wrap our minds around, but one way you can kind of get a glimmer of it is – Maimonides talks about in his Thirteen Principles of Faith, the belief in the resurrection. So what’s the resurrection? Is that souls that are in heaven, that are ascending every year on their yahrzeit [deathday], they’re going to another level higher and higher and higher. And there will come a point when the physical plane is so perfected, the only way a soul in heaven will be able to have an aliya and go higher, will actually be to make a U-turn and come back to its body. Because the physical world will be that refined, it will become –

LEVY. So basically the physical world is going to be elevated to the highest point of the spiritual so that what’s down now actually becomes up.

TAUB. That’s right. Eishet chayil ateret baala.11 That the woman of valor is a crown to her husband. The woman of valor in this sense is malchut [sovereignty], which is the lowest of the sefirot [divine attributes] of the ten sefirot, which are like the ten emanations, ten interfaces. So malchut is the lowest, which doesn’t mean that it’s the least in value, it means it’s the culmination, it’s the interface, it’s the one that actually delivers. If you want to say there’s a bridge between creator and creation, that’s malchut. And ultimately we’ll see how that’s the highest – or we call sof maaseh bemachshava techila, that the end result was the first in thought. Which also refers to Shabbat by the way. It’s the last day of the week but it was the first idea and intention. And the same thing if you look at history as a cosmic week of six work days and Shabbat being the Messianic Era. So the last era within history is actually the one that everything was initiated for the sake of.12

LEVY. You get all these different expressions you talk about, the era, you talk about the person, you talk about the time, Shabbat, you talk about the space. One of the other areas is the place. There’s a place where Shemitta [the Sabbatical Year] happens. There’s a land where Mashiach is meant to come to. Is the State of Israel part of the final redemption?

TAUB. You know, olam shana venefesh [world, year, and person],13 I mean to use the terms from Sefer Yetzira, which is one of the oldest kabbalistic texts. So there is space and there is time and then there is the human dimension. We speak about, for instance, Yom Kippur, to give you an example. It’s the holiest day and you have the Kohen Gadol, the high priest and the holiest person. And he goes into the Kodesh HaKodashim, the Holy of Holies, which is the holiest place.

So there is no question that the physical land of Israel, the holy land, is an important feature of Mashiach. Ultimately one of the expressions of a perfected world is the ingathering of the exiles and the restoration of all of the mitzvot, which largely have to do with the Land, the agricultural commandments and all of the commandments that have to do with the Beit Hamikdash, with the Holy Temple, which is in a very specific physical location in a very specific place in in Jerusalem, in the Holy land, on the Temple Mount. So there’s no question that the Holy Land is a focus.

But, having said that, I’ll tell you a story. There was a Hasid of the Tzemach Tzedek.14 The Tzemach Tzedek was the third Chabad rabbi. He was the grandson of the author of the Tanya. And he had a Hasid who wanted to move to Eretz Yisrael [Israel]. This is in the mid 1800s and there was already – I mean in the Baal HaTanya’s lifetime there was a big wave of Hasidic aliya [immigration to Israel]. So this is already a few decades after that. So this Hasid wanted to move to the Holy Land and in his particular case the Tzemach Tzedek told him, I’ll say the Yiddish, he told him, Mach do Eretz Yisroel. Make here the land of Israel.

What does that mean, make here the land of Israel? I mean Israel is a very specific [place] halachically – I’m saying there are rules for the land and there are rules outside of the land. But what it means is that ultimately there’s a process, and the process I’m describing as being Mashiach, and that process has to entail everything that’s in this world. There’s nothing superfluous, there’s nothing wasted. So in that sense, if a Jew finds himself or herself in a particular situation somewhere in the diaspora with a particular life and a story and certain challenges and strengths and certain resources, certain connections, certain whatever it is – making your life as holy as you can where you are right now is actually part of the process of how we perfect the world and we all collectively do get back to the literal Holy Land.

LEVY. Wow. So what we see today, historically with the State of Israel, is that, do you say that we are getting closer to this Messianic period? Are we getting closer to the Final Redemption?

TAUB. The return of so many Jews living in the Holy Land is certainly a positive development. We can’t forget at the same time that those Jews who are still living in the diaspora cannot be left behind. So there’s sort of a synergy, there’s a relationship between those who are in the literal Holy Land and those who are picking up the last pieces, the last sparks, refining the last sparks outside of the land of Israel. Obviously the goal though is collectively to all get back to our Land.

LEVY. So separate from that, what’s the greatest challenge that we’re facing in the world today?

TAUB. The greatest challenge? It’s not from outside of ourselves. That’s the mistake. It’s not any one force or entity outside of ourselves. It’s completely internal. I would say a lack of clarity and ultimately lack of clarity about ourselves.

Benjy Levy: Wow.

TAUB. If we would know who we are, if we would have clarity about our identity and our mission, that’s everything.

LEVY. This is across humanity. Each person needs to –

TAUB. Yes.

LEVY. And why is it – [do] you think now is a time when we’re less aware and clear of our own identities?

TAUB. I think that we’re living in a very interesting era in history right now where in some ways everything is being questioned. In some ways there’s a certain cynicism that is actually healthy. We’re rejecting old paradigms and a lot of things do need to be rejected in order to make way for truth. But when you’re rejecting so much, when you’re questioning so much, you can’t just exist in an ideological vacuum, in a void. It has to be immediately replaced with something or it becomes very dangerous. It becomes rudderless, you become lost. Which is why there’s a concept makdim refuah lamakah, that Hashem introduces the medicine before the disease. So the inner dimensions of Torah always existed, but they were generally kept within a certain, I’ll use the word elite, although I’m afraid of the connotation of the word elite –

LEVY. More exclusive.

TAUB. More exclusive, yeah. And I would say especially with the Baal Shem Tov, the teachings of the inner dimensions were democratized to a certain extent. And not just among the Jewish people, but we have a mission to spread this truth to the entire world, to all of humanity. So that is the medicine that precedes the disease. The truth is available. The deepest explanations of reality, a system for understanding reality, it’s available, it exists.

It’s been organized, it’s been – I called it the file folders before. But now we need to actually use it. So then, you ask what’s the biggest obstacle? The biggest obstacle is just us not availing ourselves of this information. Primarily about our identity. I think everything stems from that. I think once you know how to look at yourself from a perspective of divine truth, then everything else falls into place.

LEVY. So you talked about the interesting times we’re living in. How has modernity changed Jewish mysticism?

TAUB. It’s made it so much more accessible. Even in my lifetime. I’m not that old. I mean [I’m] 50 years old and I’ve seen in my lifetime how the Rambam, Maimonides,15 concludes the Mishneh Torah, the fourteen volumes of Jewish law with the laws of Mashiach. And he quotes the verse from the prophets that says when Mashiach comes, the knowledge of God will fill the earth like the waters cover the ocean bed. And I don’t know how people read that millennia ago when it was first said or even a century ago or even fifty years ago, but today it’s like literally the knowledge of God like –

Benjy Levy: It’s everywhere.

TAUB. It’s everywhere. Like, you’re sitting in this room right now, you can pull out a device, go onto the Wi-Fi, you can pull up every Torah text that is known to man and have it right there where you are. It’s Godly knowledge. I mean other knowledge too, but we’re in the midst of a refining process, so there’s other stuff as well out there. But the fact that not just Torah knowledge [is online], but [so are] the hidden secrets that people used to spend a lifetime trying to find maybe a teacher who could tell them part of it. And now today anyone with an internet connection can find out anything. That’s like the knowledge of God literally covering the face of the earth like the waters cover the ocean bed.

LEVY. It sounds so pashut, so simple, but if you were telling our great grandparents this –

TAUB. Right.

LEVY. It would blow their minds.

TAUB. Right. Or maybe they couldn’t even imagine it, right. If we hadn’t lived in it, how would we even imagine something like that?

LEVY. So what differentiates Jewish mysticism from other mystical traditions, religions?

TAUB. That’s such a good question. And I’m a little bit hesitant to answer because to answer the question implies that I feel that I have a proper understanding of other approaches, [when] the only discipline that I’ve immersed myself in is the Jewish perspective. So I don’t want to speak for other ideologies, but what I will say, what I think is a hallmark of Jewish mystical teachings and something special about Jewish mystical teachings is that – someone once asked me, it was a practical question. He was flirting with different forms of mysticism and non-Jewish forms of mysticism. And he asked me a similar question: What’s special about [Judaism]? And he said: Don’t tell me that because I’m Jewish that I have to have this automatic affinity or loyalty to the Jewish teachings. Make an argument based on the merits of the teachings themselves. So I said, you know, in other forms of mysticism, the goal is to even the scales. Sort of to get even, get off the wheel, and escape this whole thing called existence. And in Judaism, we’re not trying to even the scales, we’re trying to tip the scales. Maimonides even uses that exact imagery in the laws of teshuva, in the laws of repentance. That one action, one good deed –

LEVY. Could tip that scale.

TAUB. Which means for the whole world, right. So I think that focus on the perfectibility of the world, of the physical world, that the point of religiosity is not to die and go to heaven and have a better afterlife but really the perfectibility of the physical plane. I think that’s – I would argue uniquely Jewish.

LEVY. So does one need to be religious to study mysticism?

TAUB. No, I don’t think there’s any barrier to entry. To the contrary, well first of all, what does religious mean? You’re talking about [being] observant, doing more mitzvot. Or is it, well, maybe it’s an identity. Maybe somebody is religious because they call themselves religious. But let’s define it as someone who actually observes more mitzvot. What I would say is, you don’t have to be more observant in order to study mysticism. If you study mysticism, you will naturally become more observant. The more this perspective becomes clear to you, the more it will come out in your day-to-day life, which will naturally lead you to more observance of mitzvot. And if you never end up calling yourself officially observant, who cares? You can call yourself whatever you want. It will result in more mitzvot, which at the end of the day is what we’re talking about. What tips the scales is the mitzvot, the physical action.

LEVY. Wow. And can it be dangerous?

TAUB. Can it be dangerous? Well there was, you know, I think we would be disingenuous if we did not acknowledge that historically there was always a concern about the dangers of people dabbling in mysticism when they are not ready. I think that, for full disclosure, if we’re going to speak about this in a historical context, I think we should say that as far back as the Arizal, Rabbi Isaac Luria, from 500 years ago, that he said, and this was a radical statement at the time, that it’s not only mutar, permissible, [but it is] mutar u’mitzva,16 it is now a good deed to reveal this wisdom. So there was a concern [but] that concern became lifted as time went on. Then you have to sort of explain, well, why is that? I mean, we believe in the concept of yeridat hadorot, the descent of generations, that every generation becomes spiritually weaker than the previous one. So if it was dangerous for people who were spiritually greater than us, why isn’t it dangerous now, right?

LEVY. Maybe because we need it more?

TAUB. Because we need it more. Exactly. Precisely. So it’s on a need to know basis, and that’s how I would answer this question in a nutshell. If you’re learning it for fun, if you’re learning it because it’s inspiring, if you’re learning it because you think it’s cool, what right do you have to dabble into the secrets of the Torah? But if you’re learning it because no, I need this. I need this, I can’t function without this. There’s a famous metaphor, a story that the Baal HaTanya was asked: What gives you the right to teach the secrets of the Torah in such an open way? I mean, it it was a real challenge because historically there was that –

LEVY. Exclusivity.

TAUB. Yeah. Not from an elitist point of view but because of protecting people from information that they might not be able to handle properly. So the Baal HaTanya17 says there was a king. Once upon a time there was a king. Obviously a metaphor, you know. And the king had a son. The son became very weak and nobody could heal the son. And then a wise man appeared and said, “There is one gem that if you crush it, and you turn it into a powder, and you mix it with water, the solution that you create from it has medicinal properties. That’s the one thing that can heal your son.”

So the king said, “Well, money is no object, get that gem.”

And the wise man said, “We have it already. It’s your crown jewel. It’s the centerpiece of your crown.”

So the king says, “The crown is the symbol of my kingdom. Without a son, my kingdom is worthless. Take the jewel from my crown, crush it, pulverize it, make the solution, the medicine, and give it to my son.”

The wise man says, “There’s one more catch. He’s so sick, we don’t know if he’ll even be able to ingest the medicine.”

So the father, the king, says, “How much does he need?” The wise man says, “Well, even a drop will revive him, but he may not even be able to take in the drop.”

The king says, “That’s a risk I’m willing to take.”

The Alter Rebbe explained that the king obviously is Hashem and the son is his people. The crown is the Torah, the centerpiece gem is the secrets of the Torah, the mystical teachings that were preserved and cherished and kept set apart for so long. But now the son is weak and this is the only medicine that can revive him. And yes, it’s true that he may not even be able to ingest it. Meaning to say a lot of it may – I hate to use harsh language, it may go to waste. You may be speaking over people’s heads. You may be saying things that they can’t yet integrate. But if they can take one idea –

LEVY. It’s worth it.

TAUB. Yeah, because it saves lives.

LEVY. It’s pikuach nefesh. It’s a lifesaving obligation.

TAUB. Correct. Yeah.

LEVY. Wow. So one of your strengths and I think one of the reason your teachings resonate with so many people is you talk to the heart of relationships. [You] talk about marriage, you talk about children. So in a very personal way, how has the studies of mysticism affected your own relationships?

TAUB. It’s a great question. Wow, you’re putting me on the spot. That’s very personal. Okay.

LEVY. Feel free to give an example.

TAUB. Okay. I’ll take up that challenge. You know, I’m very into parenting right now. By right now, I mean the past maybe five, six years. I really think parenting is the foundation for so much. Like there’s so many problems that we consider to be human problems, so many disorders and emotional issues and I realized that a lot of it, if not most of it, or almost all of it, stems from parenting, like how children were raised and how utterly transformative a change in parenting is because it it it’s not just improving your relationship with your kid, it [has a] ripple effect on the rest of your child’s life and then the way they grow up and raise their children. So seeing your child as a soul. That’s a big thing. That they’re not just a person – we have certain ideas and expectations of what our child is supposed to be like, and a lot of times parents feel frustration, like this is not what I signed up for, this is not what I want. And you want to talk about a really practical application of a spiritual concept? It’s looking at your child as a soul. Not a human being who happens to have this spiritual entity inside of them called the soul, but primarily a spiritual being that happens to be in an embodiment form right now –

LEVY. Do you find it hard to do that with your own children, with your own students?

TAUB. Yes, it’s hard to do. It’s hard to do, but it’s so powerful. It changes everything. It changes the entire relationship. And you start to see the inherent goodness in the person that you’re looking at like that. The truth is we should do it for everyone –

LEVY. Everyone. But often those that are closest to us.

TAUB. Right, and it’s so important for a parent to be able to see a child this way. It’s so transformative. It changes a child’s life to be seen that way, you know, and a lot of the reason for instance – we talk about the idea of a tzaddik, a righteous person, a holy person. A lot of the reason why that relationship is so important, and I’m saying specifically, not just rav vetalmid, a teacher and a student, where the teacher conveys information and the student learns the information, but I’m saying the idea of, for instance, a rabbi and a Hasid. What’s that relationship about? It’s about having somebody in your life who sees you as a soul. That is what it is. A tzaddik sees the spiritual and they see the spiritual in you and they see that your primary identity is your spiritual identity.

LEVY. And when they recognize you as a soul, you obviously see yourself more as a soul.

TAUB. And you become aligned to it and you behave more like it and then it’s a process of integration. And what I’m saying is that every parent in their home has to be the tzaddik, has to be the rabbi who can see their child as a spiritual entity –

LEVY. So beautiful.

TAUB. See the perfection that’s already there. Don’t look at them as a project. Look at them already as whole, as intact.

LEVY. It’s the sof maaseh bemachshava techila you said, it’s starting with the end in mind.

TAUB. Yeah it is.

LEVY. Because if you see them there then they can get there.

TAUB. That’s right. They’re already there and now, if externally we have to also align it, then we’ll do that.

LEVY. Beautiful. And just to end, you know, we’ve talked about so many powerful ideas and how the teachings relate to life. Can you share a teaching? Any teaching that comes to mind or that is your favorite teaching, or something that has come with you, or that you are thinking about at the moment. Just a very short idea so we can taste what Jewish mysticism is.

TAUB. Any teaching I like?

LEVY. Anything.

TAUB. Okay. So we have been speaking a lot about Tanya. I’ll share something from chapter two of Tanya, early on in the book. We were talking about a tzaddik, a truly holy, godly person in the way they look at others. So there is a talmudic concept that if you want to cleave to Hashem, you should cleave to talmidei chachamim, Torah scholars. But in Jewish mysticism, that takes on an even deeper level. So chapter two of Tanya says like this: The Jewish People are actually not a people, they are a person. One guy. We are one organism. And the more accurate way of understanding the Jews is as limbs of a body. We are all limbs of [one] body. [This] means we’re interconnected. There is no such thing as competition, there is no such [thing] as scarcity. We’re all in this together, we are one being. But then within that body, there is the head. The head is the nerve center for the body. It integrates all of the limbs of the body, connects all of them, leads them all, that is the function of the brain. And there are certain leaders who are called roshei Bnei Yisrael, literally the heads of the Jewish People. What does a head mean? Just like a head integrates and leads the entire body, all of its organs and systems, so there are these leaders. And when you connect to such a person, this is what moves me very much. When you connect to such a person, it’s not about – here’s this great person, this great Jew, this great scholar, this great leader, let me be impressed with them, let me admire them, a little hero worship. No, no, that’s not the point. The point is we are all one body, we’re all one entity, one organism, but we lose touch with our own greatness. And there are certain leaders that when you meet that leader, you’re actually meeting yourself. You are finding your own greatness. Because they see you that way. They view you as a soul with all of its limitless potential and then it rubs off on you and you start to see yourself that way.

LEVY. Beautiful. That actually ties back to your parenting advice, because you said we need to be the tzaddik [righteous person], we need to be the rosh [head] because our children become what we see in them.

TAUB. That’s right.

LEVY. Well 10 million a month is not nearly enough. And we give you a bracha, we give you a blessing with these profound teachings that you clearly bring into your life, that you’re able to just spread more and more and more, she’yafutzu maayanotecha chutza, that they should go into the deepest depths. Thank you so much for your time, your incredible work, and I’m looking forward to seeing it continue.

TAUB. Thank you. Thank you.

LEVY. Thank you, Rabbi.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Yitzchok Adlerstein: Zionism, the American Yeshiva World, and Reaching Beyond Our Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we launch our new topic, Outreach, by talking to Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein, a senior staff member at the Simon Wiesenthal Center, about changing people’s minds, the value of individuality, and the “no true Scotsman” fallacy.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Yehoshua Pfeffer: ‘The army is not ready for real Haredi participation’

Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer answers 18 questions on Israel, including the Haredi draft, Israel as a religious state, Messianism, and so much more.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Dating Story – On Religious & Romantic Commitment

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, Dovid Bashevkin dives deeply into the world of dating.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Mental Health Journey

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin opens up about his mental health journey.

podcast

Yossi Klein Halevi: ‘Anti-Zionism is an existential threat to the Jewish People’

Yossi answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

Yabloner Rebbe: The Rebbe of Change

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Pini Dunner and Rav Moshe Weinberger about the Yabloner Rebbe and his astounding story of teshuva.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

A Letter to Those Going Through Divorce—and Everyone Else

I’ve seen firsthand the fallout and collateral damage of the worst divorce cases–and that’s why I’m sharing methods for how we can…

Essays

We Are Not a ‘Crisis’: Changing the Singlehood Narrative

After years of unsolicited advice, I now share some in return.

Essays

The History of Halacha, from the Torah to Today

Missing from Tanach—the Jewish People’s origin story—is one of the central aspects of Jewish life: the observance of halacha. Why?

Essays

AI Has No Soul—So Why Did I Bare Mine?

What began as a half-hour experiment with ChatGPT turned into an unexpected confrontation with my own humanity.

Essays

How Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe Saw the Jewish People

What if the deepest encounter with God is found not in texts, but in a people? Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe…

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

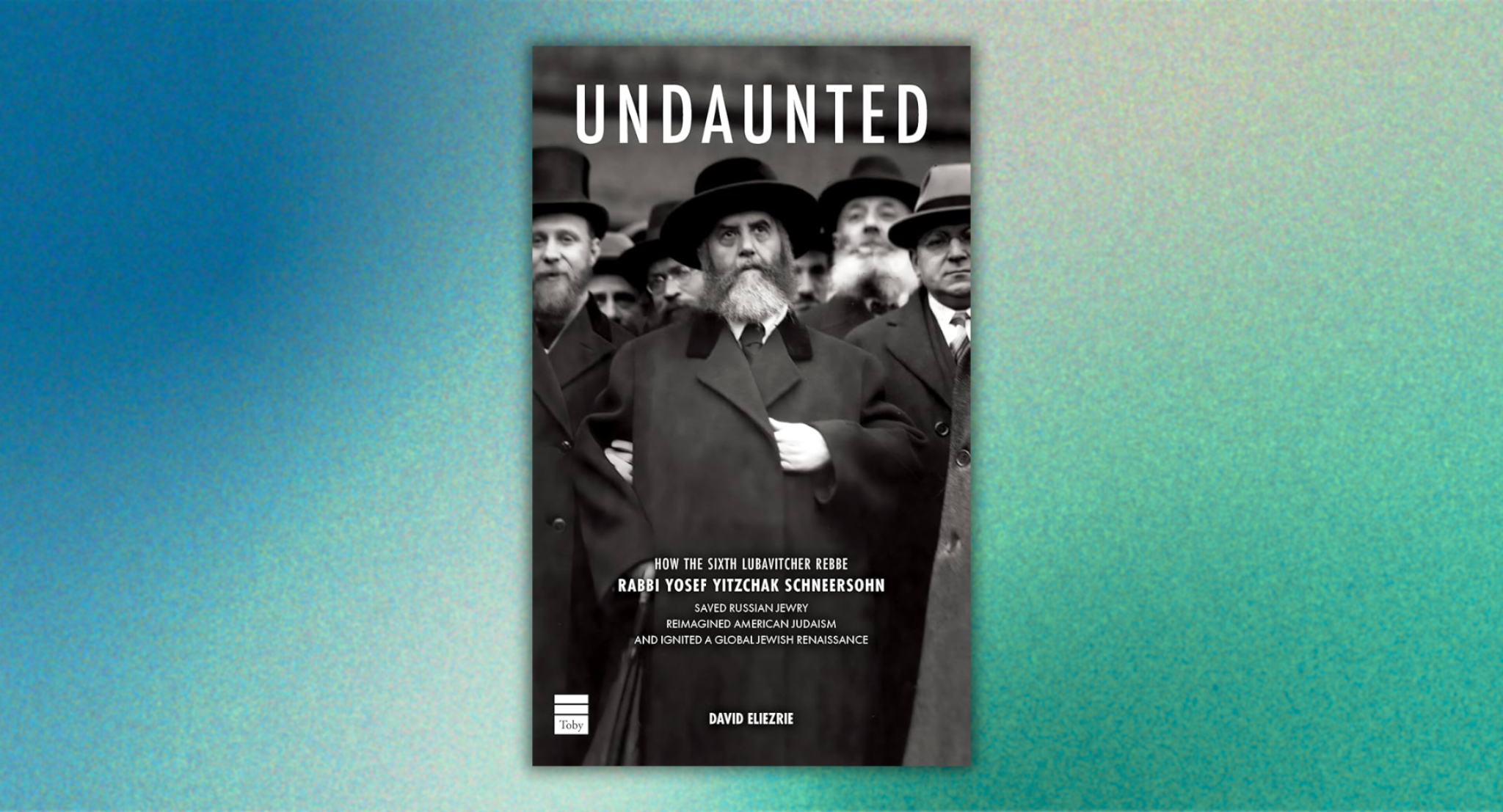

The Bibliophile Who Reshaped American Jewry

David Eliezrie’s latest examines the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe’s radical faith that Torah could transform America.

Essays

The Art of the Interview: The Best Three Interviewers for You to Know

As podcasts become more popular, the interview has changed from educational to artistic and demands its own appreciation.

Essays

Rav Tzadok of Lublin on History and Halacha

Rav Tzadok held fascinating views on the history of rabbinic Judaism, but his writings are often cryptic and challenging to understand. Here’s…

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel, head of a campus Chabad and…

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

We Asked Jews About AI. Here’s What They Said.

This series, recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit, is sponsored by American Security Foundation.

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

Talmud

There is circularity that underlies nearly all of rabbinic law. Open up the first page of Talmud and it already assumes that…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…