Zevi Slavin: ‘To be a mystic is to be human at its most raw’

Zevi Slavin joins us to discuss inherent divinity, the potential of modernity, and the perpetual experience of Har Sinai.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

As a Chabad Hasid, Rabbi Zevi Slavin’s formative years were spent immersed in the rich traditions of Chassidut and Kabbala. This upbringing provided him with a unique lens through which he continues to learn, study, and connect with others.

Drawing on his background, Slavin created “Seekers of Unity,” a Youtube channel dedicated to exploring the philosophy and history of mysticism across diverse traditions. He founded this channel with the goal of forming a community focused on creating a more intimate world together.

Now, he joins us to answer eighteen questions with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy on Jewish mysticism including people’s inherent divinity, tapping into the potential of modernity, and the perpetual experience of mount Sinai.

RABBI BENJI LEVY. Zevi Slavin, such a privilege and pleasure to be sitting with you here. We grew up together in Sydney, Australia, crossed paths in Jerusalem, Israel, and you founded Seekers of Unity, an incredible community that learns online about philosophy and different elements of mysticism across traditions. Thank you for being with us.

RABBI ZEVI SLAVIN. Pleasure to be here with you Benji.

LEVY. So this communal platform is all about mysticism. But what is mysticism?

SLAVIN. That’s a great question and a challenging question to answer because for every scholar of mysticism there’s another definition of mysticism. I’ve gravitated to two definitions, one more academic and scholarly and one more poetic. The academic one is that mysticism is comprised of three components. It is unitive experiences, unitive theories, and unitive practices. So moments in which we feel that the separation between ourselves and the world around us dissolves, softens, loosens, we feel an intimacy, a presence, a unity with all of being. That’s unitive experiences. Unitive theories is trying to make sense of that experience through the tools of human narrative, through mythology, theology, history, philosophy, metaphysics. And then practices, the practices that we enact in order to precipitate those experiences, and also the way that we act in the world knowing what we know and having experienced what we experienced, so the ethics of mysticism are the practices. So experience, theory, and practice. That’s a more academic definition.

And for a more poetic definition, there’s a wonderful scholar of mysticism, Evelyn Underhill. She was an Anglican scholar writing in the early 1900s, and she wrote that mysticism is the art of unity with being or the art of unity with reality. People think about mysticism as something escapist, we’re running away from the world, from our lives. But mysticism, in the eyes of its finest scholars and its finest mystics, is precisely how to be most present with the reality of our lives.

LEVY. Amazing. So, you know, growing up around Bondi Beach – I don’t know if you’d expect to be able to articulate such a packaged answer with the three parts from a theoretical perspective, you know, the poetic perspective. How did you get into this thing? What’s your origin story with Jewish mysticism?

SLAVIN. Sure, thank you. I grew up in a Hasidic community, which is a beautiful form of contemporary Jewish mysticism. I grew up studying Jewish mysticism. I didn’t know that it was called mysticism at the time. We were studying Chassidut. We have our own, you know, native language for it. And as a teenager, through some books that I was reading I encountered mysticism in other traditions. And through seeing mysticism elsewhere, I began to realize that that which I had been taught all along was actually mysticism. And so that introduced me to understand my own tradition better and to understand other traditions that speak in alignment with the mysticism of my tradition.

So from a very young age I was given the gift of Jewish mysticism from – really from my childhood onwards. And then through my adulthood I began to understand what it was, what was the gift that I was given in a personal way, in a way that made sense to me, in a way that also was part of a larger global narrative.

LEVY. It’s almost like you were born into this gift and your appreciation just grew with time.

SLAVIN. Yeah. I certainly did not understand what it was to begin with. When you’re a young twelve-, thirteen-, fourteen-year-old, mysticism can go over your head. But as I matured, I began to understand what it was that I was studying all along.

LEVY. Sounds like an analogy for life –

SLAVIN. Yes.

LEVY. We get it at this precious point and we only appreciate it with time.Yeah.

SLAVIN. Yeah, who was it, Kierkegaard, that said that time is the greatest teacher but it kills all its students, so.

LEVY. And also youth is wasted on the young.

SLAVIN. That’s right.

LEVY. So, you know, in an ideal world, would all Jews be mystics?

SLAVIN. I’d say in an ideal world, all humans are mystics. If we’re human, then we’re part of a shared reality. And if we’re able to slow down and appreciate that reality in which we share, in which we coexist, then we’re living in a mystical conception of that reality. So I think that to be a mystic is to be human at its most raw, at its most present. So I would say not just all Jews, but all humans, and maybe even beyond humans, maybe even creatures beyond the human realm are also in touch with the presence of reality, maybe even better than humans.

LEVY. Wow. That’s something we’re gonna have to unpack another time. But I think that’s giving a sense of the depth of mysticism.

SLAVIN. Sure.

LEVY. So what do you think of when you think of God?

SLAVIN. For me, firstly, the image or thought or conception of God is one that is always dynamic and changing. It’s never static because life is dynamic and changing. It’s a challenging conception. I think God by definition is our highest conception, and it’s the conception to which we strive. And the question of what God is or who God is is the question of what is our own highest value to which we strive. I like to think about the divine, which is maybe a bit of a softer word than God, as the totality of reality, existence itself. The Jewish mystics refer to God as Chei Ha’olamim, the life of all worlds, that which is pulsating through all of existence. And I think part of that is to understand that the divine is wrapped in mystery. And there’s a great cosmic mystery, of which we are a part, that is not separate from us. And that’s perhaps, you know, some thoughts that, some words that come to mind when we speak about things like God.

LEVY. So what’s the purpose of the Jewish People then?

SLAVIN. The purpose of the Jewish People is – as a people who stood at the foot of Sinai and had a vision of reality in which the divine disclosed itself to them, is to take that message, to put it into practice, to live lives that are in line with that divine vision of a unified reality, and to share that message with the world. You know, in, in the book of Genesis, God says that God chose Abraham because Abraham followed in God’s ways and taught his children to follow after that. Maimonides in Guide [to the Perplexed] 3:52 writes that Abraham through his conception, his conceptualization, his meditation upon God came to a deeper, true realization of God as the true reality of all being. The Mechaveh Hametziut, he uses the language of Maimonides. And Abraham, in love with that reality that he encountered, in love with his God, sought to build a family, a tribe, a nation that would live in alignment with that ethical mission and teach that to the world. And I think we as a people, the children of Abraham, have a responsibility to continue that vision, to continue that encounter that happens at Sinai, which is not just a historical event but is a perpetual event that we potentially can be constantly experiencing, and share that presence of divinity that pervades all of reality in our daily lives, both with ourselves, our families, our tribes, our communities, and then hopefully to the world as a whole.

LEVY. How does prayer work?

SLAVIN. Prayer is a moment for reflection and introspection where we’re able to step away from the chaos and noise and busyness of the world. And we’re able to center in and focus on what it is that we’re truly wanting. When we pray we’re aspiring to be the prayer that we say. The Kozhnitzer Maggid says that we do not do prayer, we are prayer. Va’ani tefilati lecha, says King David in the book of Psalms, that we become a prayer. Prayer is being in the divine presence. Prayer is being in that stillness with God. Prayer for the Jewish mystics is the place of encounter, the place of intimacy with the divine. The mystics tend to think about prayer less in a utilitarian, petitionary function where we’re coming to an external being outside of us and asking for some gifts, for some wealth, for health. Prayer for the Jewish mystics is entering into that space where we are the divine and we’re wishing, we’re bringing those things into our lives. And it’s about reminding ourselves what are the things that we’re wishing into our lives. The liturgy of prayer in Judaism is there to help us align ourselves with those highest callings of a world and life infused with divinity.

LEVY. What’s the goal of Torah study then?

SLAVIN. Torah study is, if we can think about different modalities of intimacy, of connecting. So if prayer is to connect with the divine, with reality on an emotive level, Torah study is to connect with the mind of God. The Zohar writes that the Torah predates existence by 2,000 years, and this predates time as well. So it’s not 2,000 years chronologically, it’s 2,000 years conceptually, abstractly. Torah is the blueprint of reality for the Jewish mystics. And when we put our minds in Torah, we are uniting our mind with the mind of God. We’re uniting our minds with the blueprint of reality. So it’s a form of intimacy that is often placed in parallel with prayer. But whereas prayer is seen as a place for emotional toil and a place to to fall in love with God, Torah conversely is a place where our minds get absorbed into the mind of God and vice versa. That’s sort of the dual wings of prayer and Torah, which often come together.

LEVY. Beautiful. And are men and women the same?

SLAVIN. Men and women are not the same. It would be very boring if they were the same. If we were the same, it would be a waste of time for us to talk to each other. Men and women are beautifully different, as every human is different. And men and women have incredibly powerful roles if they can embody the fullness of who they are. For the Jewish mystics, [regarding] the role of the masculine, the role of the feminine, is not just a biological role, it’s also a divine role. Within the divine, there’s masculine and feminine. There’s – we don’t say man and woman within God because that refers to a biological, or gender, but we speak about masculinity and femininity, those different aspects. And for the kabbalists, the masculine and feminine that’s in God is also within each of us. We all have masculine and feminine inside of us. And it’s about learning what it means to be masculine and what it means to be feminine from the perspective of the mystics to embody that, but they’re certainly not the same. They’re in a constant dance or polarity that enhances one another, that creates a beautiful life that comes from the merging of the masculine and feminine. So they’re certainly not the same. They’re beautifully different.

LEVY. So you – you’ve really come into contact through your online teaching with hundreds of thousands of people that are seekers of unity, that are looking for this. What would you say is the biggest obstacle to living a more spiritual life?

SLAVIN. That’s a great question. What is the biggest obstacle? From the perspective of the mystical traditions, there is a process by which we forget our true identity. The Jewish mystics refer to it as a process of tzimtzum, where the divine withdraws the divine consciousness that pervades all of reality to make space for otherness, to make space for you and I to feel like we’re independent individual beings. The Sufis speak about a process of Nisyān [forget], of forgetting, that we forget who we are. The Hindus speak about māyā, is this cosmic, you know, illusion that we that we don’t know our true reality is divine.

So from the perspective of the mystics, the challenge to knowing our true identity is part of the journey, it’s baked into the system. Without it, it would be boring as well. Without it, there would be no journey to discovering who we really are. From the perspective of Jewish mysticism, we speak about the waters of reality, the mayim rabbim, the mighty waters that threaten to drown and overwhelm us in every moment. And those are financial worries, social concerns, anxieties, traumas, these are all the waters that threaten to overwhelm us. And part of the mystical life is learning how to swim in those waters that we once drowned [in]. We never leave those waters, we never escape the waters of life, well until we pass away. But we learn how to swim and how to maneuver in those waters. When to let them carry us, when to fight the currents.

So it’s really, it’s not one aspect that makes the mystical life difficult. It’s all of life, but it’s recognizing that those difficulties, that forgetting, that tzimtzum, that that illusion is all part of the process. It’s all intent, it’s all divinely intended to create this beautiful experience and this beautiful journey that we’re on together.

LEVY. So why did God put us into these waters to start? Meaning, why did God create the world?

SLAVIN. That’s a great question. From the perspective of Jewish mysticism, God is one, right? That’s a pretty strong consensus amongst theologians, God is one. It’s a strong tenant in many traditions –

LEVY. Within the monotheistic traditions.

SLAVIN. At least within, yeah. And even perhaps beyond in some ways. So then the question stands, why did God create a reality in which there’s separation? God should have stayed in God’s oneness. If the point of reality is to come to some sort of sense of divine unity and oneness, we’re seekers of unity, why create anything at all? Why not just remain in the divine unity that was?

We say in Jewish liturgy, ba’yom hahu yihiyeh Adonai echad u’shmo echad. On that day, at the end of times, in the Messianic era, God will be one and God’s name will be one. But why create reality? Why rupture the unity that predated existence? Why enter into the noise? Why not stay in the silence, the vast emptiness of the cosmos, pre-cosmic silence, in that unity, in that blissful unity? And the Jewish mystics and mystics across traditions really answer that that unity was kind of boring. It’s beautiful and it’s great, and there’s no problems, there’s no worries as we say, but it was kind of boring, kind of lonely. And the unity that is created after a process of shevira, of breaking, which the kabbalists describe, after a process of tzimtzum, of forgetting, of losing oneself and rediscovering oneself, the unity created through the bringing together of polarities, of the masculine and feminine that did not exist before creation, that unity is a rich unity, it’s a dynamic unity, it’s an exciting unity, it’s a living unity. It’s hard to say this, because we can’t talk about God lacking anything before creation because God is full and God is perfect. But in some way, and the kabbalists do gesture in a very radical theological direction towards this, the unity that we create through the process of living out our lives, the unity that God creates through the process of creating the world, is something richer than the unity that predated existence. The unity that we’re able to find, the healing that we’re able to find in our own existence makes us richer, deeper, holier, kinder people as opposed to people that have never gone through those experiences of brokenness.

And the same that’s true for the human psyche is true for the divine mind; we’re created in the image of God. So there’s something to be gained in this journey. And it’s hard to say that because there’s really a lot of pain and a lot of suffering in this journey. But somehow it’s all in the service of creating a more beautiful, a more perfect unity. Maybe even perfect is not the right word because it’s imperfect. But it’s more rich, it’s more dynamic, it’s more alive than the unity that was pre-creation –

LEVY. And clearly that’s what God wanted.

SLAVIN. Because we’re here.

LEVY. Yeah. So does free will exist in this entire cosmos? Like where do we as individuals come into it?

SLAVIN. Free will from the perspective of Jewish mysticism, there’s only one being in reality that possesses free will and that’s the divine. Only God has free choice. We have free choice in so far as we are God, which means that we do have free choice because we are part and parcel of divinity. But it’s not a free choice that’s arbitrary, it’s a free choice that is essential. And the free choice at the end of the day comes down to the choice that we choose to be and know who we are and the things that flow from that, the ways that we behave as a result of that.

From the perspective of Jewish mysticism, the perception of free choice that we have in our everyday lives is somewhat illusory. We function under the rubric of so many predetermined variables. But when it comes to the fundamental, the essential choice, which is the divine choice of choosing ourselves, choosing the divine in every moment, that is really where free choice resides. So we don’t actually have free choice in every realm of life, but we have free choice when we’re making questions that concern divinity, and we have free choice insofar as we are divine.

LEVY. Complex.

Zevu Slavin: Yes.

LEVY. But it does exist, therefore.

SLAVIN. It does exist. It exists in true moments, which is interesting because from a phenomenological perspective, our choice feels equal across scenarios, across across a variety of choices –

LEVY. But it’s not in reality. From the perspective of Jewish mysticism, it’s not. That we have so many natural, innate, biological routines that we follow. And there are special moments in life that can be daily or that can be more rare where free choice really steps in. And I think there is a sense where we have a feeling that this is, that that this moment, whatever that moment is, is a moment where there are really true paths that are open in front of us –

LEVY. Well it relates to the Talmudic statement that hakol bidei shamayim chutz miyirat shamayim, that everything is ordained except for the capacity to have that awe of the divine, i.e. those moments that you’re describing.

SLAVIN. Correct, correct. So there are special moments where that capacity steps in. But otherwise, there’s a lot that we just don’t have control over and that’s okay.

LEVY. So in those moments, we’re trying to advance a better world. That better world in mystical teachings is referred to as Mashiach. What does Mashiach mean?

SLAVIN. Mashiach means a state of being in which we understand who it is that we truly are and we live in alignment with our true identity. Who we truly are from the perspective of mysticism is God. We are the divine. We are a chelek Eloka mima’al mamash. We are literally a part of the infinite. And that which is a part of, that which is truly infinite, any part of it is also infinite. The Jewish mystics say that etzem, something that is essential, k’she’atah tofes b’miktzaso atah tofes b’kulo. When you have any part of the essence, you have all of the essence.

So our true identity is divinity, is God. Mashiach is the Messianic consciousness. It is realizing that, is living in that. And we can have moments of that. The mystics speak about a geula pratit or Mashiach pratit, an individual Messianic consciousness that saints or even ordinary people can inhabit in their lives. Someone who’s saintly is having that for longer stretches in their lives. You know, they’re in that plateau of true consciousness. From the perspective of Jewish mysticism, when enough people are able to step into an individual consciousness of their own true, divine identity and begin to act and live that way with divine degrees of compassion and kindness and presence and wisdom, then automatically our world becomes a different world. We’re no longer in opposition to one another, in competition with one another. There’s no longer a reason to hate one another because we understand who our true identity is and that’s a shared identity. We understand that we’re not separate from one another but that we’re fundamentally ontologically interbeing with one another. We share each other’s reality. There’s this deep arevut of our very souls, a deep mixing, a deep interbeing of who we are. And the world that is built on that premise is the Messianic world.

LEVY. So is the State of Israel part of this process? Is it part of the final redemption?

SLAVIN. It’s a hot question, a tricky question. It depends who you ask. There are certainly Jewish mystics who feel and felt that the modern State of Israel is part of the Messianic process. And there are Jewish mystics who did not feel that way. Jewish mystics are, as Jews, they also love to disagree and they’re not monolithic. There are many different visions and ideas within the world of Jewish mysticism. And there was a very contentious internal debate in Jewish theology, and in Jewish mystical theology, over the past century [on] precisely that question of whether the State of Israel is the beginning of the Messianic process or whether it’s not, whether it’s detached from it and there’s other things that need to happen in order to bring about a mystical consciousness –

LEVY. And some even think it’s pushing us away from it.

SLAVIN. Some people think that it’s pushing away, yeah –

LEVY. So what does Zevi Slavin think? You know, you lived in the place, you’ve read the prophecies, you’re immersed in the mystical teachings.

SLAVIN. Sure. As a Chabad Hasid, I have a lineage that I belong to. I belong to a specific, specific family of mysticism. And that’s the Hasidic tradition and within that, the Chabad Hasidic tradition. The Chabad Hasidic tradition was part of the ideologically, was part of the camp that did not see the modern State of Israel as the the beginning of the Messianic redemption, as opposed to other great Jewish mystics like Rabbi Kook and others. The Chabad mystics felt that there were – that it was teshuva, it was repentance that needed to precipitate the Messianic consciousness as opposed to statehood, as opposed to nationalism.

So as a Chabad Hasid, I feel that way too. I feel that the political manifestation, the historical manifestation of a return to our homeland is insufficient without a return to a true identity of what it means to be a Jew, what it means to be human, what it means to be a living part of the divine infinite. And I think the miraculousness by which the State of Israel came into being is certainly part of the divine process, the divine plan. But from the perspective of the Chabad mystics, the lineage which I proudly belong to, it in and of itself it is not inherently part of the redemptive process unless it’s precipitated by a a return of the individual to their true selves, which is what teshuva means, return.

LEVY. It’s so interesting because you look at post-October 7th Jews, the October 8th Jews, and it’s the State of Israel that has precipitated a lot of their Jewish identity and rediscovery.

So without having to respond, I wonder what the Lubavitcher Rabbi [Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson] would say when he sees so many people returning to themselves through the State of Israel.

SLAVIN. Yeah. You know, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson danced a fine line between being one of the most fierce and vociferous lovers and supporters of Israel while never crossing the line that his predecessors set against the acknowledgement of the state as part of an inherently Jewish process. So Rabbi Schneerson played a very, very sensitive and delicate balance in that space. And Rabbi Schneerson was very critical of voices within the Hasidic world that were critical of the state of Israel and refused to see the hand of God at play. Rabbi Schneerson was furious [at] fellow leaders of the Jewish, of the Hasidic Jewish, world that didn’t acknowledge the divine intervention, the miracles that we saw clearly with open eyes. And on the other hand, Rabbi Schneerson did not openly choose to acknowledge the state as part of the Jewish process. So it’s a tricky place to be in and what Rabbi Schneerson would have said now is anyone’s guess.

LEVY. We’ll see when Mashiach comes, I guess.

SLAVIN. When we make it, when we make it happen.

LEVY. So what is the greatest challenge facing the world today?

SLAVIN. What’s the greatest challenge?

LEVY. Or one of them.

SLAVIN. I think, wow. I can only speak from my own perspective, and I think that the greatest challenge that I’m seeing in my own life and in the lives of those around me is the inability to focus on what really matters. We’re living in a day and age where we’re so thoroughly inundated by waves of distraction and entertainment that there’s barely a moment to sit in silence and ask who are we and what are we here for. And when we open ourselves to the silence, that’s when we hear the voice of God.

You know, the Jewish mystics speak about the prophetic tradition. And there’s a debate within Jewish theology whether prophecy ended or prophecy continues. It’s a bit of a contentious subject. But there’s a very beautiful Jewish mystic who says that prophecy never ended, it just went underground. That the midrash says that God threw truth to the earth, into the earth. V’tashlach eretz artzah –

LEVY. Emet.

SLAVIN. Emet, thank you. And his beautiful reading is that the voice of God, the voice of truth still speaks, but none of us get low enough down to the ground to hear that voice. We’re too busy, we’re too noisy, our head is up in the air, caught up in the airwaves. But if we can slow down then we can hear the voice of God, which is present in every moment, because revelation never ends.

LEVY. It’s what the liturgy calls the kol demamah daka, the still, small voice.

SLAVIN. Precisely, precisely. And I think that the greatest challenge perhaps, or one of the greatest challenges, is that we don’t have the time and opportunity and spaces in our lives to hear our own inner divine voice –

LEVY. Well, there’s a noise.

SLAVIN. There’s a noise.

LEVY. The noise of this life. And it just distracts us from that opportunity.

SLAVIN. Yeah. But that’s why we have practices. That’s why we have mystical practices, which is the third part of the experiences, theory, practices. Practices like Shabbat. Practices like kosher, where we eat in mindfulness. Practices like prayer, where we stop for an hour a day, and we’re able to sit in that silence. It’s those practices that allow us to open that space for the potential to hear our own voice, the divine voice.

LEVY. So in this unique time we’re living in, has modernity changed Jewish mysticism?

SLAVIN. Inevitably. We live in the world. The mystics, despite popular imagination, live in this world. And many, many scholars of Jewish mysticism even argue that Chasidut as a movement is fundamentally a product of modernity. They see it as a modern movement in its democratization, in its empowerment of the individual. In so many ways, Hasidism is modernity. From the perspective of the Jewish mystics, particularly of the mystics of my own lineage, the Chabad mystics, the world is not at odds with the divine, the world is divine. And therefore, everything that happens in reality is to serve the divine purpose. The Baal Shem Tov, the founder of the Hasidic movement, taught that the the intervention, supervision, the hashgacha of God is present in every single moment; every single leaf that falls and lands on a caterpillar is divine intervention out of great divine mercy that the caterpillar should have shade. So of course, modernity is part of that divine process as well.

And based on the teachings of our Sages that lo bara Hakadosh Baruch Hu davar ba’olamo elah lichvodo, that nothing is created in this world besides for the glory of God, for the greater unity of all reality, so modernity is certainly part of that process. The question is, how do we tap into the potential that is in modernity without being distracted by all the challenges that it brings to bear as well. And if we can learn to ride the wave of modernity, then we bring Mashiach, we bring that Messianic reality precisely where we are. We don’t run back to the Middle Ages, we don’t run back to antiquity. We live in the moment. For the Chabad mystics that came from Europe to America, America itself was part of that divine process of a country of freedom, of democracy, of individuality. They saw that for many Jewish leaders, it was a threat to religion, a threat to the mystical life, the light of interiority and reflection and contemplation. For them, modernity, precisely the modernity of the America in which they took up their mantle, became part of their mission. You could say that Jewish Chabad mysticism today is not just deeply modern, it’s deeply American as well. So the mystics are never really afraid of history. They’re there to embrace history because they see the divine hand in all of human history.

LEVY. So one of the interesting things about your work, and even in this conversation, you quoted other mystical traditions, mystical sources, even mystical religions. What differentiates Jewish mysticism from other mysticisms?

SLAVIN. Yeah, you know, it’s a great question and I love the way you phrased it. When I first began to explore mysticism from a comparative, from a global, from a human standpoint, I was so enamored by the commonality, by the overlap, by how much they had, by how much they shared with one another, how much they had in common. It blew my mind frankly as a teenager –

LEVY. It’s unity, no?

SLAVIN. Yeah, it is unity. It is unity. And it’s all humans that are tapping into that same divine mystery, and working hard to try and listen carefully to it, and coming out with beautifully similar thoughts about the structure of reality, about how we’re best to live in this life, to live a life of flourishing, of eudaimonia. What interests me more as the years followed was actually the differences between them. The commonalities became so abundant that seeing their differences became beautiful for me. And for me, every tradition has its own genius. And for me, the process of trying to understand this global human narrative is to understand the unique contribution of each tradition.

LEVY. Can you give a sentence on one or two and explain what the Jewish one is specifically?

SLAVIN. Sure. Yeah. Absolutely. We’re sitting here in a shul, you know, a sanctuary of Jewish prayer and worship. So maybe we’ll talk about the genius of Judaism and – but I could also share about other traditions as well. I’m deeply in love with all of the world’s mystical traditions. And they went from being this unknown enemy and foreign objects to me to being great objects of love and admiration, and I’m very glad that I’ve had that journey. I think the genius of Jewish mysticism is precisely the way, and this is something that we’ve been talking about in the conversation, precisely the way in which the divine and the mundane, heaven and earth, are so beautifully, seamlessly integrated. The greatest Jewish mystics in Jewish history were almost always also invariably the greatest Jewish halachic thinkers. We think about people like Rabbi Joseph Karo, who wrote the Shulchan Aruch, which is kind of the textbook of Jewish law. Rabbi Joseph Karo was a bonafide, thoroughbred Jewish mystic, a student of the Arizal, one of the greatest mystics of Jewish history. So, and this is true for almost every great halachist, they were also tremendous, tremendous masters of of the inner aspects of Torah or the inner aspects of life –

LEVY. The irony is the people that look at the Jewish law don’t even realize someone like the Vilna Gaon or someone like that, that they were so steeped in mysticism.

SLAVIN. Precisely, precisely. People think about the dispute between the Hasidic world and the Misnagdic world as between the mystics and the rationalists, the mystics and the halachists. It’s not true. The Vilna Gaon was one of the greatest kabbalists of his generation, bar none. So – and this is true throughout the generations. This is true, speculatively, going back to the Talmudic Sages, people like Rabbi Akiva, Rashbi – great, great masters of halacha and Jewish mysticism. All the way through to the Middle Ages, people like Maimonides, I believe, was a great, great mystic as well as a great halachist, etcetera. And the list really goes on and on.

LEVY. So that’s what makes Jewish mysticism unique.

SLAVIN. So I think what’s happening in Jewish mysticism is that there’s a way in which the most abstract, the most transcendent, the most ethereal becomes the most material, the most realized, the most present. And Jewish mysticism and the genius of Jewish mysticism, and perhaps the genius of Judaism, is knowing how to take that most divine, that most spiritual, embedding it into our everyday mundane lives, into our business lives, into our family lives, into our communities in ways that are thoroughly, thoroughly intertwined in ways that there is no separation, that it’s precisely the body that becomes the vessel for the soul and the soul that becomes the vessel for the body in Judaism. Where halacha – people from outside look at Judaism as legalistic, right? One of the great criticisms that Christianity launched against Judaism is that it’s too legalistic, too ritualistic, too rigid, too much following the –

LEVY. The letter of the law.

SLAVIN. The letter of the law as opposed to the spirit of the law. Nothing could be further from the truth. A true life, an authentic Jewish life is completely intertwined between body and soul, spirit and matter, in a way that the two become inseparable. Yaakov Yosef of Polnoye, a student of the Baal Shem Tov, wrote that leyodei chein, to those that know the – how do you translate chein?

LEVY. Grace.

SLAVIN. So to those who know the truth of grace, something like that. Leyodei chein, which is a beautiful phrase in itself, they know there is really no separation between guf and neshama, between body and soul. They’re all one. And that is something that the Jewish genius knows how to bring into action, into our lives where our kindness, our material, our tzedaka, our generosity are all living embodiments of the spirit of the divine that lives and breathes through Judaism.

LEVY. So does one need to be religious to study it?

SLAVIN. I don’t know exactly what people mean when they say religious. Religious – the Latin etymology of religion is religare, that which is bound, the one that is tied. I consider myself religious insofar as I choose to bind myself to a people, to a heritage, to a nachala, to an inheritance. And I think in that sense all Jews are bound by the very existence of who we are. One doesn’t opt to become a Jew. A Jew, as far as I understand, is bound, is religare, is religious in that sense. And from the perspective of Jewish mysticism, particularly from the perspective of the Lubavitcher Rabbi, my rebbe, but also going back all the way to the Sages of the Talmud, there is no Jew who is not full with mitzvot like a pomegranate seed, says the Talmud. From Rabbi Schneerson’s perspective, every single Jew was was bursting with divinity, with – do we want to call that religiosity? I don’t know, but –

LEVY. So does one – so you’re saying naturally anyone can study because naturally everyone is religious?

SLAVIN. It’s not just that we’re naturally religious. We naturally are God, we are divine, right? Religion is is something of a human construct –

LEVY. But therefore it’s accessible and encouraged for everyone?

SLAVIN. Yes, absolutely. It’s who we truly are. It’s that which is inalienable from us. I think religion – you know, there’s a beautiful line: We encounter the divine, the absolute, the transcendent, which overwhelms us and we respond with the construction of religion. And that’s a helpful construct at times, sometimes it’s an unhelpful construct. Carl Jung, the famous philosopher and psychologist, said that religion sometimes is there to protect us against an encounter with the divine, because that encounter can be overwhelming and destabilizing. And sometimes it protects us too much –

LEVY. Those two are a contradiction essentially. It’s either a response to experiencing the wonder as an encounter or it’s protection.

SLAVIN. It could be a response that is protective. It could be that we need to create structures of life and community so that we can live in alignment with that –

LEVY. So then one’s an expression of the other, I guess.

SLAVIN. Potentially, potentially. There’s a very beautiful line from Leonard Cohen that religion, the Jewish religion he’s speaking about, is the shell, the crustacean that emerges around the agitation that the Jews encounter at Sinai. And there’s a pearl that emerges, and around that pearl there’s a shell. And for him the shell is religion. That holds it. But he talks about the agitation because that’s what gives birth to the pearl deep, deep under water. So we’re agitated by the divine and we are the pearl, right? We’re the pearl that emerges naturally. And religiosity is a context to hold that, to give a framework for that pearl to shine and be protected. Sometimes that pearl can be stifling. Sometimes the shell can be stifling and the pearl can die inside. So religion, like any man-made construct, can be conducive or it can be counterproductive.

LEVY. The other line from Leonard Cohen that really supports that is: It’s the cracks that let the light in.

SLAVIN. Precisely, precisely.

LEVY. Because that’s where it comes from, comes through.

SLAVIN. Precisely. But for that you need both shell and cracks, right? Because if you had no shell, and you – then there would be –

LEVY. Then the pearl would never see the light.

SLAVIN. Precisely. Precisely. You need to have space to hold, to hold back the light, tzimtzum, and also to allow the light in. So there’s a fine balance. And the mystics throughout traditions, and also in Jewish mysticism, are both reticent and critical of religion as a social enterprise and also supportive because they understand that that’s a balance. That we both need it and don’t need it. We both need to have those walls and also deconstruct them as we live in that reality.

LEVY. So could mysticism be dangerous?

SLAVIN. Certainly, certainly. Mysticism can be very dangerous and it has been dangerous. It can be dangerous on the individual psychological level. It can be highly destabilizing. The mystics basically unanimously teach that the self that we think we are is not who we really are. That there’s a deeper self beneath that, there’s divine self, there’s no self in other traditions. For someone to be told that their identity of self is something entirely other than they think it is, it can be very destabilizing. And mature responsible mystics will make sure that a student of mysticism is first in a healthy, built-up place, where there’s a healthy sense of self, before we begin to deconstruct it. We need those walls before we can begin to crack them –

LEVY. Well, you can’t deconstruct something that doesn’t exist.

SLAVIN. Precisely, precisely.

LEVY. So you need to build the structure first.

SLAVIN. You need to build the structure. That’s true. Mysticism can also be dangerous on national levels, on scale, not just for the individual. Mysticism has been co-opted by fascism, has been co-opted by movements that wanted to take the most powerful human impulses, that sense of unity that people can feel and to turn that, to weaponize that against another type of people. You know, the Third Reich was filled with mystics unfortunately. So, mysticism is not a silver bullet. Mysticism is certainly dangerous.

LEVY. But that wasn’t mysticism itself per se. That was an ideological co-opting, weaponization of mysticism and using it to –

SLAVIN. I would like to believe so, yeah.

LEVY. Express something else.

SLAVIN. As as someone who’s who’s dedicated their life to to the pursuit of mysticism and to the understanding, to the education of mysticism, I would like to believe that mysticism at its best, a true expression of divinity through the eyes of the mystic and through the life of the mystic, is a life of kindness and compassion and forgiveness and tolerance and presence. And we see that again and again, embodied by mystics, by great mystics of all traditions past and present. I would like to believe that when mysticism turns violent, when it turns hateful, when it turns xenophobic – and I would say that happens within Jewish history too and we should be honest and take responsibility for that – that is not the best of mysticism. That is mysticism acting in response to a fear, to a threat, to a perversion of ideology. But we can’t ignore that. We can’t pretend that mysticism is all just strawberries and rainbows. We have to be aware that mysticism – and even today in the Jewish world, mysticism has been and continues to be co-opted for hateful projects. And we have to make sure to be vigilant that mysticism is used for –

LEVY. So the positive application that you believe it should be comes down very much to relationships. How has it affected in a very personal way relationships in your own life, whether it’s with friends, with family, with colleagues, with strangers? Yeah.

SLAVIN. Yeah.

LEVY. Can you think of anything practical that can give us a sense of that?

SLAVIN. Certainly. I mean, even in the very question. So the last clause that you threw in there with strangers. I don’t have a sense of strangers in my worldview. [Through] the metaphysic that I’ve been raised on within the Hasidic world and have come as an adult to understand in my own ways and have been thoroughly persuaded by, the notion of a stranger is a non sequitur. It’s an anathema to my entire Weltanschauung, to my entire conception of reality. Because I’m not estranged from from anything if everything is the divine unity which I am –

LEVY. What about less familiar people? Because the Torah does use the term ger –

SLAVIN. Yes.

LEVY. Which can be used in the context of someone that’s either an alien or stranger or someone that you don’t usually sort of have familiarity with.

SLAVIN. Sure, sure.

LEVY. So you’re saying ultimately beneath the surface, you have a familiarity with anyone and everyone and everything.

SLAVIN. There’s a deep sense in which that deep familiarity already exists whether we know it or not. If you sit down with someone that you’ve never met and you have a true DMC, a true deep meaningful conversation. Within a short time you learn – you’ll see quickly that there are shared fundamental hopes and aspirations, anxieties and fears. It doesn’t matter even if you can barely communicate with them, you don’t share the same language.

LEVY. So can you give an example of where this has come through as a relationship?

SLAVIN. Yeah, I mean I think that the point here is that there’s a sense in which we understand that we’re not separate from anything or anyone, and that includes both the human world and the more than human world. And when we’re able to walk through life and feel that presence, feel that intimacy that is precipitated by that capacity – I’ll give you a practical example. I’ve been filming. I produce content for the channel Seekers of Unity. And I’ve been filming an interview series called, “I’m Jewish, Ask Me Anything,” where myself and a friend will sit down with a large whiteboard and we’ll pop up ourselves in a public university campus, in front of a museum, somewhere with a nice amount of traffic. And we’ll just sit for a few hours and allow people to come over and ask questions.

We’re living in heated times. There’s no surprise there. We’re living in a very divided country. Democrats versus Republicans, this one versus that one. We’re living in a world where to be Jewish is itself a triggering and a dangerous thing to be publicly. And that could be terrifying. There’s all kinds of reasons for us to feel alienated and estranged from one another. And to feel like the enemy is perhaps it’s – there’s a threatening unknown in the enemy. And what I found in these experiments that we’ve been doing, that we’ve been filming and sharing with the world, has been that if you open up a space, if you don’t believe that, if you don’t believe that the other person is out to get you fundamentally, if you don’t believe that they’re fundamentally other than you, and you open up a space to meet them as a fellow human in the image of God, as a fellow image of the divine, you see those walls fall right away.

I mean, I show up as a very proud, very identifiable Jew and we set up the table near very, very vocal, very vociferous pro-Palestinian, anti-Zionist rallies that often, unfortunately, too often gray off into anti-Semitism. And seeing the the way that people look at me with hatred, with animosity, with fear, until they’re able to to sit down – for those that are brave enough to sit down with a Jew, and to be received like a fellow human, to be encountered as a fellow manifestation of divinity. All of a sudden those walls fall away and those perceptions and assumptions about one another fall away. And we can enter into a space where we’re talking about shared human concerns of how we can create a world where there’s less suffering and more prosperity for all humans, for all images of the divine. So for me that conception of reality, the mystical conception of reality is a very real and motivating way in which I choose to live my life. And I’m of the belief that if we’re able to step into that consciousness, we’re able to step into spaces where we don’t see each other as enemies. We see each other as fellow humans struggling with a complex reality. We’re all struggling with those great waters that threaten to drown us. But if we can hold out an arm to one another, then we can learn how to float and swim together as opposed to trying to push someone else down so that we can breathe in the waves.

LEVY. It’s like the verse mayim rabim lo yochlu lechabot et ha’ahava, that the great waters can’t put out the love that can come from –

SLAVIN. That’s right, that’s right. From the Song of Songs. U’neharot lo yish’tfuha and rivers cannot – which by the way, I never thought of this until now. That mayim rabim lo yuchlu lechabot et ha’ahava, that when you have love, when that, when the ahava is there, and ahava – the gematria of ahava is thirteen, which is echad. That when that unity is there, when that love between humans is there, then all those mayim rabim, all of those tumultuous waters can’t drown us. Because that love allows us to see each other as fellow people that are struggling in those waters.

LEVY. Or maybe they can’t drown us because we become buoyant.

SLAVIN. That’s right.

LEVY. And we’re able to – the water’s still there.

SLAVIN. That’s right.

LEVY. But we’re able to rise above it, so to speak.

SLAVIN. Correct. We don’t escape the waters. We rise above. But I think that we rise above it precisely by holding on to each other. And even by holding on to people who we think are – have our worst intentions in mind. I mean we have to be responsible and safe and adults. But I think if we can learn to hold our hands together in those waters with love, if we can extend a hand of love, then lo yish’tfuha then there’s no there’s no extinguishing it. There’s no, there’s no drowning it.

LEVY. Amazing. Well it’s beautiful how we’ve had the opportunity to bring learnings into our discussion. What I’d like to end with is a short idea that is just a teaching. Can you share one mystical teaching? One Jewish mystical teaching that inspires you or that may inspire us.

SLAVIN. Sure, sure. I think a core – a paradigm shift for me as a teenager was a re-understanding of this Jewish teaching that I was raised on but only understood for the first time through the lens of mysticism and precisely through the lens of a global, human perspective of mysticism. And I think this very seamlessly ties into the themes that we’ve been discussing here.

There’s a commandment in Tanach, in the Hebrew Bible, to imitate God, to walk in the ways of God. Vehalachta b’drachav, to walk in the ways of God. And it’s a command that has been picked up by other Abrahamic faiths, imitatio dei is what it’s referred to in Latin, in Christianity. It’s imitating the divine. It’s a very challenging thing to imitate God. God has no form. God has no definition. God is only known by negation for the medieval philosophers. How do we imitate something that is formless and infinite, right? How do we ,what does that mean to imitate the infinite? And the rabbis, the Sages of the Talmud already grappled with this question. They say, what does it mean? How can one walk in the way of God? And the way that they phrase it is very beautiful – the rabbis have a very vivid, sensorial imagination of their theology. Their theology is not dry and abstract like in other traditions. It’s very – as we’ve been saying, it’s very material, it’s very lived. And they say that Tanach, the Bible, describes God as a consuming fire, as an eish ochla. And they say, how do you walk in the path of a consuming fire? You’re going to be consumed as well. Which, if we can extrapolate what they’re meaning more sort of mythologically, if you try to emulate, if you try to live a life of infinity, you’re going to be burnt. You have no identity, no responsibilities, you have no choice. You’re just an infinite undefined blob of being. What does that even mean?

So – and I think that’s the imagery the rabbis are getting at when they say God is a consuming fire. And the rabbis say something very beautiful that God, it’s – we don’t know the essence of God. The essence of God is a mystery, it’s our mystery. We don’t know the essence of ourselves either, right? Or not even either. We don’t know which is the essence of God, which is the essence of ourselves. But we know God through God’s actions. And this is a famous tenant in Rabbinic Judaism. And the actions of God that the rabbi specify in the Talmud are three precise, three specific actions that take place in Chumash, in the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, which is that God clothes the naked, Adam and Eve, God buries the dead, Moses, and God visits the sick, Abraham after his circumcision. And they say by imitating God, we – that is how we become God. And we imitate God precisely in those ways. I think part of the genius here is that within the biblical text, there are so many actions that God partakes in. God smites the Egyptians. God hails hail upon the firstborns. God turns Sodom and Gomorrah. God destroys the world in a flood. And the rabbis are telling us that there are many, many ways in which reality manifests, in which the divine manifests. We have a choice to make.

And this goes back to the question of choice that we raised earlier. In what way are we choosing to imitate the divine? In what way are we choosing to imitate to imitate reality, to be reality? Which aspects of reality are we choosing to highlight? And for the Jewish mystics, their answer is that to be in line with divinity means to act with divine levels of compassion, presence, love, kindness, forgiveness in ways that make no sense. The act of burying the dead is called chesed shel emet, it is an act of true kindness because the dead cannot repay you. They’re gone. To visit the sick means to put aside from yourself, to move away from your own health, to jeopardize even your own health, to be in the presence of someone else who needs you. To clothe the naked means, who are the most vulnerable people in our society that don’t have clothing on their back, they don’t have a roof over their heads, they don’t have food in their mouth? And in what way can we be there to share with them those things? And when we’re able to do those things, we realize that those people that are sick, that are naked, that are dying are not other than us. And what it means to imitate God is to realize that if we are divine, they are divine, and we are both in that shared divinity. And to imitate God means to act in a way that their well-being is not separate from our well-being. And for me, for me that’s been a pivotal Torah about what is it that we’re choosing? What aspect of the infinite are we choosing to emulate?

LEVY. I find that really beautiful because the specific imagery used is of this consuming fire –

SLAVIN. Yeah.

LEVY. And what is the first encounter that Moses has with God? It’s a consuming fire that doesn’t end up consuming –

SLAVIN. Correct.

LEVY. Because perhaps the paradox is that if you really tap into the essence of that consumption, it doesn’t actually consume because it’s infinite. And it’s going to burn forever with this passion –

SLAVIN. That’s right.

LEVY. And I think we’ve seen that passion not just through this conversation, I’ve been blessed to see years of your life. And we give you a blessing that you’re able to really help seekers of unity find that unity, even though it’s the seeking that is the unity. And that you can continue and grow, and at such a young age to have really mastered so many different traditions, that understanding that really that mastery will just continue and continue and continue. We never actually fully master it. But through that growth we can all be inspired. So thank you so much.

SLAVIN. Amen. Thank you Benji. Good to be with you.

LEVY. Good to be here.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Ora Wiskind: ‘The presence of God is everywhere in every molecule’

Ora Wiskind joins us to discuss free will, transformation, and brokenness.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Dr. Ora Wiskind: How do you Read a Mystical Text?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Dr. Ora Wiskind, professor and author, to discuss her life journey, both as a Jew and as an academic, and her attitude towards mysticism.

podcast

Yehoshua Pfeffer: ‘The army is not ready for real Haredi participation’

Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer answers 18 questions on Israel, including the Haredi draft, Israel as a religious state, Messianism, and so much more.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

Rachel Yehuda: Intergenerational Trauma and Healing

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we pivot to Intergenerational Divergence by talking to Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, about intergenerational trauma and intergenerational resilience.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

AI & Halacha: On Transparency and Accountability

Rabbi Gil Student speaks with Rabbi Aryeh Klapper and Sofer.ai CEO Zach Fish about how AI is reshaping questions of Jewish practice.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Three New Jewish Books to Read

These recent works examine disagreement, reinvention, and spiritual courage across Jewish history.

Essays

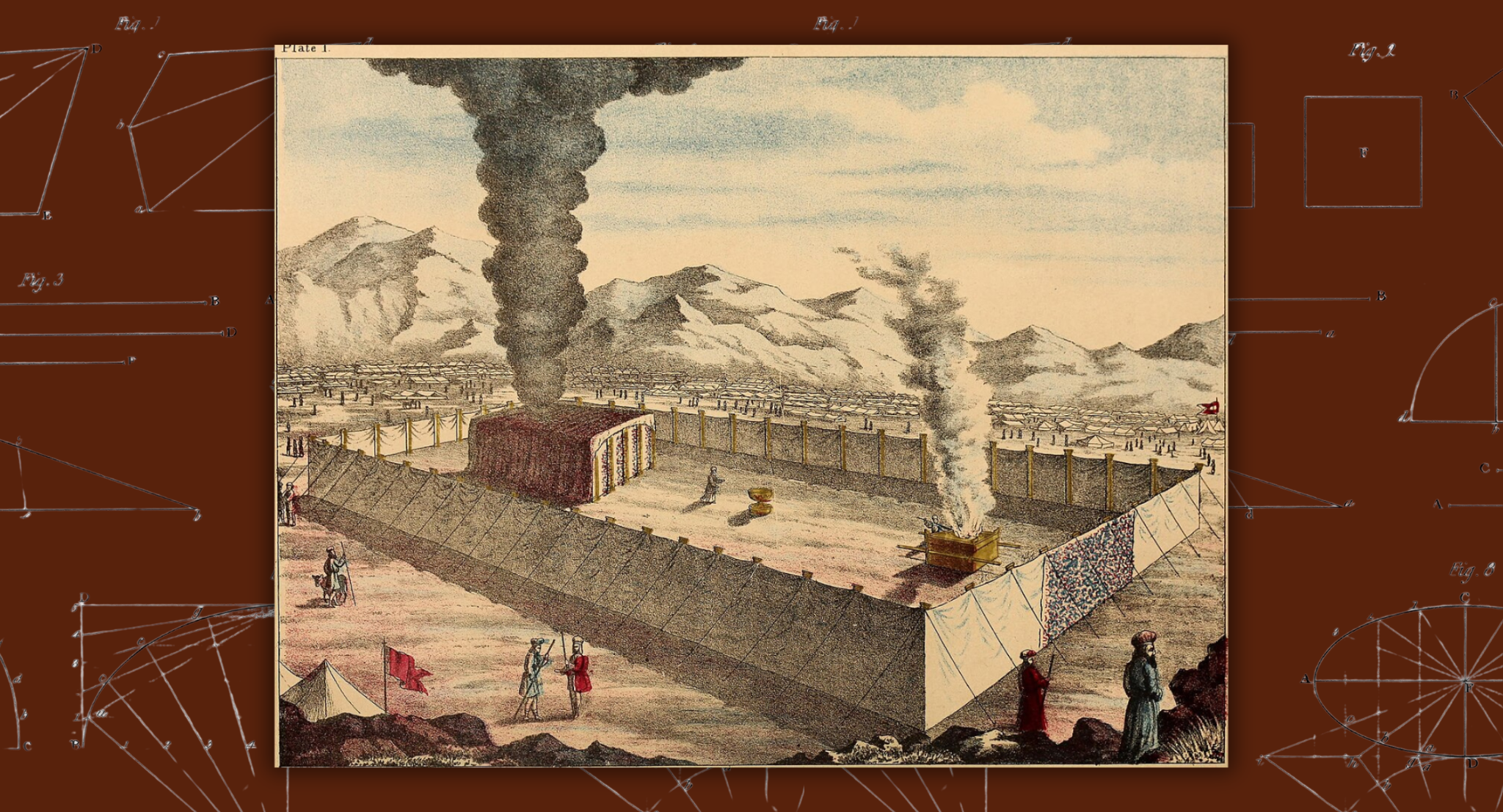

How Generosity Built the Synagogue

Parshat Terumah suggests that chesed is part of the DNA of every synagogue.

Essays

The Gold, the Wood, and the Heart: 5 Lessons on Beauty in Worship

After the revelation at Sinai, Parshat Terumah turns to blueprints—revealing what it means to build a home for God.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

A Letter to Those Going Through Divorce—and Everyone Else

I’ve seen firsthand the fallout and collateral damage of the worst divorce cases–and that’s why I’m sharing methods for how we can…

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

The History of Halacha, from the Torah to Today

Missing from Tanach—the Jewish People’s origin story—is one of the central aspects of Jewish life: the observance of halacha. Why?

Essays

We Are Not a ‘Crisis’: Changing the Singlehood Narrative

After years of unsolicited advice, I now share some in return.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

AI Has No Soul—So Why Did I Bare Mine?

What began as a half-hour experiment with ChatGPT turned into an unexpected confrontation with my own humanity.

Essays

How Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe Saw the Jewish People

What if the deepest encounter with God is found not in texts, but in a people? Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe…

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

We Asked Jews About AI. Here’s What They Said.

This series, recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit, is sponsored by American Security Foundation.

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel, head of a campus Chabad and…