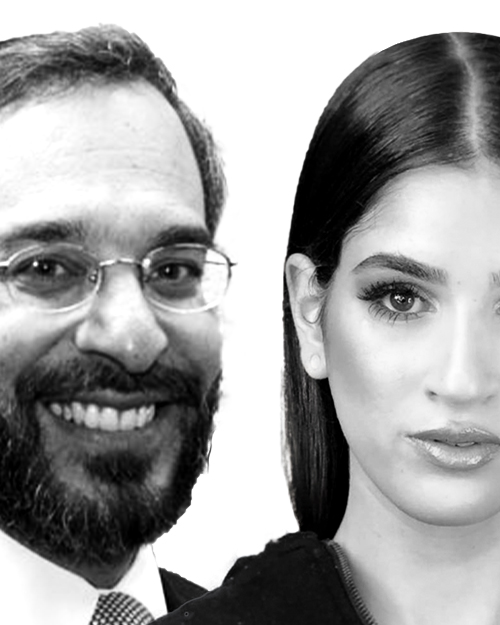

David Bashevkin & Malka Simkovich: Can Judaism Survive the AI Revolution? (Fifth Year Anniversary)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin and historian Malka Simkovich discuss the future of technology, AI, and the Jewish People. This episode was recorded live at the Moise Safra Center as 18Forty celebrated its Fifth Anniversary with our community.

Summary

On June 29, Eden will be hosting a webinar to speak in detail about the vision for this project. In order to register please click here or email info@edenbeitshemesh.com to find out more.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin and historian Malka Simkovich discuss the future of technology, AI, and the Jewish People. This episode was recorded live at the Moise Safra Center as 18Forty celebrated its Fifth Anniversary with our community.

We begin with words from Sruli Fruchter and Mitch Eichen delivered at the program, as well as questions from the audience to conclude. In this episode we discuss:

- What is the point of academia and asking questions?

- Will AI replace rabbinic authority or the conversations we have on 18Forty?

- Is there any topic that 18Forty will never take on?

Introduction from Sruli Fruchter begins at 9:05.

Introduction from Mitch Eichen begins at 12:50.

Interview begins at 17:26.

Dr. Malka Simkovich is the director and editor-in-chief of the Jewish Publication Society and previously served as the Crown-Ryan Chair of Jewish Studies and Director of the Catholic-Jewish Studies program at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. She earned a doctoral degree in Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism from Brandeis University and a Master’s degree in Hebrew Bible from Harvard University. She is the author of The Making of Jewish Universalism: From Exile to Alexandria (2016), Discovering Second Temple Literature: The Scriptures and Stories That Shaped Early Judaism (2018), and Letters From Home: The Creation of Diaspora in Jewish Antiquity, (2024). She has been a three-time guest on the 18Forty Podcast and led our Book Journey on the essence of antisemitism.David Bashevkin is the founder and host of 18Forty. He is also the director of education for NCSY, the youth movement of the Orthodox Union, and the Clinical Assistant Professor of Jewish Values at the Sy Syms School of Business at Yeshiva University. He completed rabbinic ordination at Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, as well as a master’s degree at the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies focusing on the thought of Rabbi Zadok of Lublin under the guidance of Dr. Yaakov Elman. He completed his doctorate in Public Policy and Management at The New School’s Milano School of International Affairs, focusing on crisis management. He has published four books: Sin·a·gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought, a Hebrew work B’Rogez Rachem Tizkor (trans. In Anger, Remember Mercy), Top 5: Lists of Jewish Character and Character, and Just One: The NCSY Haggadah. David has been rejected from several prestigious fellowships and awards.

References:

“18Forty: Exploring Big Questions (An Introduction)”18Forty Podcast: “Philo Judaeus: Is There a Room for Dialogue?”18Forty Podcast: “Daniel Hagler and Aryeh Englander: Can Jews Who Stay Talk With Jews Who Left?”

The Nineties: A Book by by Chuck Klosterman

Einstein’s Dreams by Alan Lightman

Time Must Have a Stop by Aldous Huxley

“Laughing with Kafka” by David Foster Wallace

The Most Human Human: What Talking with Computers Teaches Us About What It Means to Be Alive by Brian Christian

Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas R. Hofstadter

“Failure Comes To Yeshivah” by David Bashevkin

For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_forty

WhatsApp: join here

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Bashevkin: Hi friends, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore different topics balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin and today we are playing the episode from our live five year anniversary celebration. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18Forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings and weekly emails.

18Forty first launched its first episode in May of 2020. So this year, the beginning of June 2025 really marked our five-year anniversary. And I’ll be perfectly honest with you, I get very uncomfortable like reflecting or thinking or taking your pulse in how you’re doing, particularly with 18Forty, which you know, has felt like this Sisyphean imagery of like pushing the boulder up the mountain and feel like you’re never going to get there. And from our very beginning, which really began before our first episode, my first email with really our co-founder, Mitch Eichen, was already in 2017. And we had no idea in the dreams of what we actually could create, would create, but it really felt like an important moment, not to reflect and retell our story, but for me at the very least, just to say thank you, to express gratitude.

What I have found over the course of my life, and thank God, I’ve had the opportunity to have some really exciting accomplishments. And you know, when you spend so much time on any one accomplishment, and I’m sure many people can identify with this, whether you’re a hobbyist, a woodworker, you’re a writer, whatever it is, music, you spend so much time thinking about a certain moment or reaching a certain milestone or producing something, and then when you finally get there, more often than not, there’s an initial, you know, excitement, but then you’re always like left, or at least I’m left with this sense of like emptiness, like, the sense of like, what now, what’s next? And you feel like you have to restart again from scratch and rebuild yourself.

And what I have found is that when it comes to taking stock of your own accomplishments, if the exercise is just an extended pat on your back—we’re number one, we’re so amazing, here’s the highlight reel of all the great things that we’ve done—while that may be nice, I have found that at least on a very personal level, it leaves me feeling even emptier than I did before. You feel like you’re conditioning yourself, reconditioning yourself to associate your self-worth with your accomplishments. And instead, because I’m so used to that feeling and I’ve been to … whenever you participate in these live events, it can be draining and it can be exhausting.

So when this idea of like coming together and celebrating was really first conceived of, and it really was conceived of by a member of our team who I’m sure many of you are familiar with, Sruli Fruchter, who’s our Director of Operations, he’s been really incredible in professionalizing and building our community. I’m just incredibly grateful for his work and leadership over these years. He started as, you know, really an internship over the summer and it’s just been incredible growth. And he pushes, he says, “No, it’s important to come together.” And the one thing that I was fairly insistent upon is that this shouldn’t be a celebration of just like accomplishments, which is nice and there are things to celebrate. What was most important to me was an opportunity for gratitude, an opportunity to reflect not on how great you are or what you did and what you didn’t do wrong or what you could do better, but just reflection as a vehicle for gratitude, having an opportunity to thank all of the people who brought you to this point in this endeavor.

And for me, that is incredibly important. I’ve always felt very personally connected. It’s not a job for me, it’s really a mission, it’s a quest. And 18Forty has been such a privilege and gift in my own life of feeling welcomed in our community’s lives and being welcomed, really, into the lives of our listeners.

And we came together and it was such a beautiful evening. It was at the Moise Safra Center, absolutely beautiful, overlooking New York City. And it really for myself was an opportunity to get up and thank so many of the people who brought us to this moment, whether it is Mitch and his lovely wife Annette Eichen who really were the initial catalyst for this very idea and were our first and only supporters when we first started. But the people who came in that room, it was such a beautiful mix of supporters and listeners and friends coming out and just what brings us all together is not any one answer.

I was looking at that room, what struck me were how deceptive looks were. So many people introduced themselves and then would tell me what yeshiva they’re an alumni of. We had a fairly strong showing of Shaar HaTorah and ToMo alumni. I was very impressed with that. But really, it was such a beautiful slice. People came from Boro Park, people came from different parts of the city and Long Island. It was really, really lovely, but these types of evenings, how do I put it? It is not my normal constitution to thrive in these events. I’m a little bit of an introvert. I think I do better on a microphone tucked away in my office than at live events, which I love, I really do, but they can be draining, they can be exhausting. But this was energizing, and the reason why it was energizing is because it was powered by gratitude. It was powered by a thank you. It was not … the spotlight was not on any one person, the spotlight was on a collective, on us as a community.

And that’s why I am so excited to share the conversation that I had with our two-time guest. This is the third time that we are sitting together in dialogue, but we turned it around. Dr. Malka Simkovich. Many long-time listeners should be familiar with her work and her voice. We have had her on two earlier episodes and she is always a fan favorite, and we invited her to really lead the conversation and have a conversation together with myself. We framed it as whether or not religion would survive AI. And I know for a lot of people, that’s a strange question to gather around. Is 18Forty just taking advantage of the AI craze or whatever it is?

I want to invite you, I did this myself and it was really, especially for those who have been listening for a long time. You may have never even seen this because our YouTube channel was so terrible initially. It’s not great, but it’s getting there, thank God. It really is getting there. And if you could take a moment and subscribe to our YouTube channel, it really helps kind of strengthen the platform, so it would really be appreciated.

But go back, and if you could go, you could sort the videos. Go back to the very first 18Forty video, which is almost, I wouldn’t say it’s a perfect description of what we created because it doesn’t really describe anything. It was more about a question and a feeling, but in that very first video, the very opening of that video is a question about how the internet, how modernity, how this new wave of technological modernity is going to affect the interiority of our lives. That what has been at the heart of 18Forty has never been one specific topic or one specific answer, but it is that big question, the biggest question of questions, which is the question of how to live, how to find meaning, how to find purpose in our lives.

And from our very inception, at the heart of that was the question of the different feeling that it felt different. Something, I believe, changed over the last five years in 2020. And we talk about it in this conversation when we first started. What was that new sense of, we are now entering a new era, we are entering a new … almost period in history? And we had thought of 18Forty before COVID, before October 7, before ChatGPT, but in many ways from our founding inception, these were those big cosmic questions that we were always primed and always ready to think about together as a community.

So really, it is my greatest privilege and pleasure to introduce, albeit it is not live, but the recording from our live event, and allow me to just say thank you once again. Milestones are most exciting to celebrate when they’re powered by gratitude, and I am filled with gratitude, with appreciation for this moment, for this opportunity, for our listening community, for, God willing, what will come next, what we will build next together. It is my greatest privilege and pleasure to introduce with great appreciation the 18Forty five-year celebration with brief words from Mitch Eichen, Sruli Fruchter, and a conversation with myself and Dr. Malka Simkovich.

Sruli Fruchter: Good evening everyone and welcome to 18Forty Forward, a celebration of five years of questions. For those who don’t know, my name is Sruli Fruchter, and I’m the Director of Operations at 18Forty, and we are so excited to have you all with us here today.

In 1913, Franz Rosenzweig went through something of an existential crisis. He didn’t have 18Forty to listen to. He was a promising young historian with great acclaim and a great future ahead of him to join the academy. The professors were hungry for him and they were so excited to see the scholarship that he would produce and that he would ultimately put into the world. And Rosenzweig, at this point in his life, was debating whether he was going to convert from Judaism to Christianity, but he was also thinking about another thing. What was the point of academia? What was the point of all these questions and ideas and topics that these academics were so enamored with?

And part of what he came to, and part of what he realized was that ultimately questions in and of themselves are meaningless. Answers in and of themselves are meaningless. If we’re asking questions for the sake of asking questions and we’re giving answers for the sake of giving answers, then we’re ultimately missing the main point. It’s the people, the people, the person within the scholar who really deserves the attention. Questions are only relevant insofar as they help the person who is seeking out an answer, help them find some sort of comfort, some sort of consolation, some sort of community. What Rosenzweig recognized was an idea that lies at the heart of 18Forty.

Beyond the numbers of 2.2 million podcast downloads and 30 plus topics and 300 plus episodes, beyond all of that lies what 18Forty is really after. The people in our community. The mothers and fathers, the students and children, the rabbis and leaders who are looking for something more, who are looking for a forum to explore their Judaism, to explore modern ideas, and to explore how we find meaning in a chaotic world that continues to pull away at the seams.

And that is what brings us here tonight, to celebrate five years of asking those big juicy Jewish questions as we all know and savor for, that touch on our personal lives, that touch on our Judaism, and that bring us to a better place of who we are. And so I’m so excited to welcome you all here tonight. And I want to first give a huge thank you to the entire 18Forty team for the last five years and for making tonight possible. For Dovid, to Dina, to those who can’t physically be with us. We have Yehuda here as well, Cody, and Gabriella, and Rivka. And of course, we want to thank our community. The people who listen to the episodes of 18Forty, who send us their stories, who trust us with the most intimate and personal parts of their lives and to follow us into this crazy world asking these questions that loom larger than life and trust us to be there with them with honesty, openness, and depth.

And of course, I want to thank all of our donors and supporters and partners, without 18Forty would not be possible and I want to specifically thank the partners for tonight and give a special thank you to our thought partner catalysts Renan and Nicole Eges, Nachman and Esther Goodman, Janet and Lior Hod, and the Paul E. Singer Foundation. Really the support and the partnership is what makes everything we do possible.

And of course, we would be entirely remiss to not thank our founder. Not just David, but our co-founder Mitch Eichen who—now, how’s this for a philosophical question?—who was with 18Forty before 18Forty existed. I want to bring Mitch on to the stage to talk a bit about where 18Forty has come from for the past five years before we head into tonight’s conversation with Malka and David.

Mitch Eichen: Thank you, Sruli. All I can say is wow. And I look out at this room and I could never think when we started this thing, when 18Forty wasn’t even 18Forty yet, that this is where we’d wind up in 2025.

So how did we come to 18Forty? I was disappointed in the foundation that the Jewish day school laid in helping people make the transition to secular college and the secular world. And I felt that there were too many unexplored questions when people left day school, things that they didn’t talk about, things that the rabbis never told them. And I was looking to actually do something to revolutionize the day school curricula.

So I spoke to some rosh yeshiva, I got shlepped to the JLI people at 770, I spoke to some other major philanthropists and I had no takers. So I spend my winters in Florida and I was at Kiddush and I was talking to this young rabbi. And I was talking to him about the problem that I perceived and he said, you’re absolutely right, there’s a major problem. I said, well what are we going to do about it? He says, I know just the guy you should talk to. He’s the Director of Education in NCSY, he’s one of the smartest people I know and you have to talk to him because if anybody could solve this problem, it’s him.

So in November of 2017, yes David, November of 2017, I called David Bashevkin and I started talking to him. And he said, yeah, interesting problem, maybe we can do something about it. And David basically wanted to get rid of me and I said, no, let’s talk again next week. The next week, the next week. And David just couldn’t figure out how to get rid of me. He says, who’s this shmendrick? I just can’t get rid of this guy. He says, would you like to sponsor my Haggadah? I said, no, I don’t want to sponsor your Haggadah. I want to solve this problem. So I came back to New Jersey in, I guess it was May or June of 2018. We met in Teaneck at Dougie’s which is not exactly a gourmet delight and we were talking about this problem.

And then I introduced him to the rosh yeshiva I’d been speaking with and they hit it off really well and then David went back to speak to him on his own. And we realized that we couldn’t solve this problem at the day school level. The day schools were too fragmented. Everybody was doing their own thing and there was so much fear because everybody was in fear of the donors, they were in fear of the trustees, they were in fear of the parents.

So David, being David, said let’s bypass them and let’s take this online into the virtual world. So now this is the summer or fall of 2018 and it was a revolutionary idea. I said, I love this. I said, come to my house in Florida and let’s brainstorm this. That was January 2019. And we’re sitting there and we’re brainstorming out this idea and he says, give me some names. I gave him a bunch of names and he says, how about 18Forty? I said, 18Forty, what is that? And he explains it to me, and that’s where this thing was born.

We started putting together all these topics that I thought needed to be explored that the Jewish world had stayed away from, that they were afraid to tackle. And slowly but surely, David started to record podcasts, one after another, and then they sat in the drawer for the longest time because David was afraid to launch them. How would the Jewish community respond to this? This is too revolutionary. You know, what are the roshei yeshiva going to say? You know, what is the community at large going to say?

And then finally the courage came, it was around COVID time, and we realized it was time to go online. The world was screaming, you know, for something virtual. The whole world was shut down. We launched and the rest is history. And I will say that we couldn’t be here without each and every one of you. 18Forty exists solely to serve the needs of the community, not to serve our own needs. It has grown well beyond our wildest expectations. And to quote the Beatles, it’s been a long and winding road to get to where we are today, but we are only at the beginning of our road, only at the beginning. We’ve accomplished so much, but there’s so, so, so much more left to be done.

And what we hope is that the next five years, you know, shows a level of exponential growth which dwarfs the last five years. And we can’t do it without the support of you, the support of all your friends. So we ask you to leave here today, spread the word, all your friends, your community, everybody you talk to, and of course, open your checkbooks if you can. And if you can’t, get somebody who can open their checkbooks because we have such vision, you know, to take this thing to another level, different podcast series, different interviews, different debates, more videos.

And ultimately, maybe even, because of all the material that David has created over the years, ultimately maybe a library of curricula that the day schools can ultimately tap into to realize the original vision. So with that, I want to introduce, and it’s my great privilege to introduce my very good friend, David Bashevkin. And by the way, when I say good friend, I mean it. Everybody is David’s good friend. I don’t have that many friends. So when I say good friend, I really mean my very good friend David Bashevkin, and Malka Simkovich, who I think is just a magnificent scholar who we’re going to learn from.

David Bashevkin: It’s much less scary than my nightmares have been the last three weeks. But it’s nice to be up here. Malka, is your mic on?

Malka Simkovich: Is this on?

David Bashevkin: Yes.

Malka Simkovich: Hi, David.

David Bashevkin: I want to begin by saying two things. A, Malka, thank you so much for being the moderator, for joining us for this conversation, and for being here from really the very beginning. You had us on twice. Really a round of applause for Malka. I’m so grateful.

From the very beginning, the only reason why when Sruli first had this idea, let’s get together in person and talk about what we’re doing, the only reason why I said yes is because I said it would give us an opportunity to show gratitude, to show hakaras hatov, to show appreciation for our community, the 18Forty community.

We should not have lasted this long. We should not exist right now. It was a dream that started in just conversations back and forth. And the fact that we are here today, I believe, is really the divine assistance, the siyata dishmaya that we have always addressed questions, issues that are tethered to our lived experience. They’re not up here in an ivory tower but tethered to that lived experience. And we have that special divine assistance because we’re dealing with what people deal with in their lives. So I don’t want to talk anymore. We always have long intros. This won’t be a long intro. Malka, the floor is yours.

Malka Simkovich: I have never interviewed anybody for a podcast. I actually have no experience in this, so you’re all going to have to help me, and David, you’re going to have to help me. And I’m going to start with a question that actually comes from the outside. It comes from the world of academia, it comes from the ivory tower, and emotionally it comes from a little bit of jealousy. I have to say, watching the success of 18Forty makes me think a lot about impact and a lot about where people should invest their time. And I want to know from you because you’ve written books, two? And you’re working on another one. And you lecture, and you teach, what do you think is unique about the podcast medium that you invested so much of your time in it, and what can it offer the Jewish people that these other platforms do not bring to the table?

David Bashevkin: It’s an awesome question when you think back in history. Someone, one time, asked me, tell me the most distinctive feature of the Jewish religion. What is unique about Judaism that is different than most other religions? And I think the most distinctive feature of Judaism is the bifurcation of a Written and Oral Torah. That we have a Written Torah that remains static, that is unchanging, that has a claim on our lives, so to speak, that models that claim that we’re born into. And then there is a part of the Torah, and I don’t mean Gemara and Mishna, I mean, there’s a part of Torah that always remains oral, that is a product of the intimacy of our lives.

I think what is unique about podcasting is that it really allows you to engage with the most concentrated manifestation of what I would call Torah Sheba’al Peh—the Torah that emerges from the speaker. Meaning, instead of reading a book, instead of listening to a lecture, what’s different I think about podcasting is that it always remains tethered and connected to somebody’s lived experience.

I think in our community, we’re very good at two types of questions or two types of lines of inquiry. We’re very often told what we should feel, like you should feel this way, you should feel that way. We get a lot of that. We also get a lot of what you can feel, which is nice. That’s like, imagine what your life would be like. We engage in both of those. Podcasting allows you to do something very different and that’s, address the question of how do you feel right now? How do you feel? Instead of just focusing on something aspirational, and instead of just focusing on something that’s more, let’s say, pedantic, or this is what you should do, it allows you to connect all three and have them in dialogue with each other.

Malka Simkovich: David, what I hear you saying is that there’s something relational about the podcast because you’re in literal conversation with a partner and that in the middle of that encounter, there is a dynamism, there’s a creativity, and there is surprise.

And very often, and I speak maybe from experience, when an academic is isolated and working day in and day out at their desk in their home office for years on one project, and they’re going deep into that project and fantasizing about the dozens of people who will read the book, if they’re lucky, they’ll get to a couple hundred, but at the end of the day, you’re in a conversation with yourself and you also don’t know the end result. You don’t know once it’s subject to inquiry, what the responses will be. And it could be that you’ve created a house of cards and in fact, the argument is not well established and well-founded.

So I want to ask you, in this world of relationships and in these hundreds of conversations that you’ve had, I’m sure you’ve been surprised many times, and I could ask you what moments most surprised you, but I want to ask you a different question. Were there ever conversations that you had where you were speaking with someone who is an expert in their discipline, in their field, and they in an encounter with you, surprised themselves because in that relational moment, they actually realized that maybe they were looking at something not in a full way or not an accurate way. I’m sorry for putting you on the spot, but I’m just curious.

David Bashevkin: I’m thinking a lot about myself. It’s hard to know who’s, like, changing their minds actively while you’re in the middle of conversation. One of the things that was unique about us from the very beginning, and we just had him back on, is we had this guest named Ari Englander, who was somebody who had left the community, and still interacts with people who come in.

And what’s really fascinating is we created a platform that allows for somebody to kind of talk out their methodology and their pain of leaving, but in the process of doing that, and this happened in the last podcast, they bring up and they already have that nostalgia and they’re pulled back to the community. Because when you’re able to be in conversation with somebody and talk about your religious life without the usual responses that I think we’re all primed to, you’re doing it wrong, you’re not doing it right, you got to get it done, make it … like, that impatience that we have with ourselves, which is a voice that’s probably shaped since you’re in 11th grade and you know, your rebbe or morah is talking to you and yelling, you did it wrong, and do it again. All of those things, they stunt our ability to have religious conversation.

And I don’t mean religious conversation, you know, when, how to make uh, I don’t know, how to light Shabbos candles. I mean a conversation about what animates us religiously, what nourishes us religiously. And what I think is so important in these conversations is that when you’re having sincere conversation, it allows you to reformulate your relationship to the subject matter itself. Meaning something that may have caused you pain, like Judaism, like rabbinic authority, like any of these topics that cause everyone pain, what conversation allows you to do is to go through this topic and disassociate it from that pain that I think we all carry.

And I think that happens in conversation and it sometimes happens when people listen. Sometimes we pull them back into their pain. That happens a lot. We get calls a lot. Very often we can pull people back into their pain because they hear somebody talking about an issue that hurt them. That’s something they went through.

Malka Simkovich: You’re framing the function of your work in the realm of emotion, and I find that really interesting. I don’t know the numbers, but I imagine that there are thousands of listeners who feel complacent or comfortable and not in a negative way, when I say complacent, but really are quite comfortable with their Judaism. Do you think that we’re in a crisis moment of faith? And what about those who come into conversation with you and they say, listen, I think what I think, I’m very confident about it and I’m not looking for transformation, in fact. Are you speaking to them in a different way?

David Bashevkin: I do think we are in a very real point of crisis. Not everybody agrees with me on this, but I can’t think of another time in all of Jewish history where rabbinic leadership, where the leadership of our community was this divided. And that’s very destabilizing for a lot of people. It may be that that was always the case, but I think it’s much more obvious right now on a lot of hot-button issues that I prefer not to list out right now, so I don’t have a panic attack live on stage, because they are listening. But no, but there are certain issues that like … and when you see there is not consensus, when you see that the story that we had as children that, you know, you follow the rules and there are the people who make the rules, it’s so much simpler. The complexity that we are facing at such young ages, in our early twenties, in our late teens, is in many ways, to me, unprecedented because we have access to so much more information. We are interacting with so many more communities. And the issues that we are confronting are larger than anything we’ve confronted, I think, in all of Jewish history right now.

Malka Simkovich: That’s a huge statement.

David Bashevkin: It is.

Malka Simkovich: And I’m gonna have to…

David Bashevkin: Push back.

Malka Simkovich: Well—

David Bashevkin: PB. A little PB?

Malka Simkovich: You said it, not me.

David Bashevkin: Push back. Yeah.

Malka Simkovich: A little bit. I was taught in graduate school to never say the word unique. Nothing is unique. You can say distinctive. And also this is very obnoxious because it’s just more rules, you know. But I was very careful to never say unique. And when we talk about modernity and we use words like unprecedented moment, every generation of Jewry has viewed itself as living on the cusp of modernity because you don’t see what’s beyond your own generation. So when I think about Jews of the first century BCE in Egypt, they were living very modern lives. The questions that they asked were questions about technology. In fact, technology is a Greek word and techne means art, just saying. So think about that.

But is it really unique when we’re talking about really how to walk the tightrope of devotion to our ancestral tradition and to do it with emotion and with love and sincerity and authenticity, and also to contend with new ideas and to fall in love with culture, whatever aspect of culture touches us? Is that a unique question?

David Bashevkin: I don’t think any of that is unique and I do also appreciate that we shouldn’t call any time period completely unique, but I do still think that we live in a very unique time period. I’m trying to paint the picture of the night when it hit me and I felt it like a hundred pounds weighing on me as I was, like, trying to fall asleep at night. A very, one of the most common questions I get is, what’s with your obsession with sleep? Sleep is my formative anxiety. I could tell my life story by going through the anxieties that I had at every stage in life. So when I was in my first anxiety, like my childhood love anxiety, was being able to fall asleep. That’s fourth and fifth grade. And then, you know, seventh grade was sleepovers, eleventh grade was the dentist that lasted way too long.

Malka Simkovich: I hope you didn’t sleep through the dentist.

David Bashevkin: No, no, no. It’s separate … Can I share something right now? Can I get real for one second? Have you ever been in the car and heard the radio ad for dental phobia? Have you ever heard that? It’s a real ad on the radio. You’ve probably never heard it because you probably don’t have a debilitating case of dental phobia. But I’m one of those people. I listened to it and I, like, shushed everybody else in the car, like shh, I gotta get this number down. And I called the dental phobia guy. I actually had a meeting with him just to do a basic teeth cleaning that I hadn’t had in 10 years because it was so debilitating. And he said, “Sure, we can do it, but it’ll cost $12,000 to put you to sleep to clean your teeth.” And I got over my dental phobia pretty quickly. One, two, three.

But coming back to that question of, like, being able to fall asleep. We are not a podcast that deals with Israeli politics. We are not. There are many podcasts that do it much better than we do. We are not a podcast that deals with politics in general. But what I think in many ways October 7 accelerated was a tripartite trauma that I still think we’re in the middle of, which is the 2020 trauma of COVID, where when society shut down, people moved into their homes. And then we got out of that, so to speak. And then we had October 7, which we’re still in the middle of. And then right after October 7, we now have this, what I think is the seminal crisis of our time, which is the advent of AI.

And I think those three are intermingling with one another that are destabilizing the very foundations of our identity of what it means to build lives, what it means to find satisfaction in your life, what it means to contend with your own existence. These are questions that seem very highfalutin but they’re underneath, I think all of the everyday questions. Questions of when to get married, having children, how to raise children. These are not new questions. What I think is unique about this time is that society is moving so quickly, it is moving so fast, that we do not even learn the new tools we have to explore these questions.

So what ends up happening is we sometimes freeze, we get paralyzed, we go back to the old conception. There’s a lot of nostalgia. There’s a writer named Chuck Klosterman I think, who writes about this, in the 90s, this obsession with nostalgia. Do you remember what the first Game Boy looked like and Nintendo and all this stuff. What’s that for? That’s a reaction to trauma that we feel destabilized. We’re looking for a time where it made sense.

And right now if you are growing up and you are 22 years old, stepping into the world for the first time, it is a very scary and confusing world and you’re aware of it. You’re very self-aware and you’re also aware of how it’s different than every other generation that came before you. So that’s what makes it new.

I’ll end with this, and I think this in many ways kind of captures it. I’m going to say one complimentary thing about myself, because I’m usually so self-deprecatory. But one of the coolest things that ever happened to me is that when I took my AP English exam, I had already read the book that the reading comp section came from. That’s cool. That … I felt very cool. I felt like I should have automatically gotten a five on that AP. I did not. I did not automatically get a five on that AP.

The book that it came from that I remembered, and I know exactly what story it was, is a book I’ve quoted many times. It’s a book called Einstein’s Dreams. I would urge everyone to read this story. Every chapter of the book tells the story of a town that operates under a different conception of time. So you have one chapter where time is a sense, where time is like one of the five senses, which is believe it or not, he ends the story, someone who is time deaf, he says, cannot speak, can’t talk, which is a very profound idea.

They have one story in there, and this is what I’m getting at, which is the story of what if time lasted forever. The chapters are like three pages. It’s written by Alan Lightman. He teaches literature at MIT. He’s a Jewish scholar, he’s a wonderful person. So this story is what if time lasted forever. And it says society would break up into two groups. There would be the nows and the laters. The nows would be trying to do everything right away, accomplish … I have so much time I could do everything. The laters are going to procrastinate. Ah, why get started now, I have all the time in the world.

The story ends with who suffers the most. He says the people who suffer the most are young people who are starting projects. They’re never able to get anything off the ground. Why? Because they have to ask their parents, who have to ask their grandparents, who have to ask their great-grandparents. If people live forever, if time is forever, then you’ve got to ask everybody’s permission. That’s what it’s like living in a world and making decisions with the internet in many ways. We feel beholden to so many other opinions. We have access to so many other communities, that I think for many people when they’re starting out their life, they feel so lost. They feel so lost and they can feel lost in the middle of their life.

And what I think what we are able to do is tether this journey of personal exploration, of finding out who I am as a person and have that in dialogue with tradition, in dialogue with the community, in dialogue with all of the context of our lives, instead of just plucking one person and their problems or their issues, we’re able to really explore the interiority, a word that we use too often, of people’s lives. And I think the moment that we have now is, people have a hard time getting their lives off the ground because there are so many voices, explicit and implicit, that are just clowning out who we are. What do I want as a person?

Malka Simkovich: The most traumatic book I ever read as an adolescent was Aldous Huxley’s Time Must Have a Stop. Has anybody read Aldous Huxley, Time Must Have a Stop? Don’t read it. It’ll ruin your life. If you have a little bit of existential angst, it will amplify it in a very upsetting way. But that’s essentially the narrative where they find the elixir of eternal life, and then at the end, they discover these people who have long been enjoying this elixir, and they’ve deteriorated. Anyway, don’t read it. But you can look it up on its Wikipedia page. I guess it has one.

So first of all, going to your question of the crisis of young people. On the one hand, I hear you saying that there’s a directionlessness, that there’s a lack of motivation when you know that everything is going to be changing constantly, you don’t know your place in it. And what you see 18Forty doing is providing an anchor, a set of questions, and maybe not a set of answers, but certainly framing for how to ask these questions, and a safe place in which to have conversations about those issues.

But David, you’ve also talked about being hashkafically homeless, and I’m wondering how you balance these two things. On the one hand, you’re offering a way for people to find answers, to make choices, and in making those choices, to reject other paths. When you choose a shul, when you choose a synagogue, you’re also making a decision to not go to other synagogues. And of course, the same is the case for schools and for communal institutions that you support. Where do you give your charity? And so there are decisions that all of us at all ages have to make that require us to make certain choices. And so do you really think that there is a possibility and also is it a value to kind of try to transcend those boundaries that separate us within our own communities?

David Bashevkin: That’s a really great question. It’s a profound question. The term that you use, that I use, came from a friend, which I use, called hashkafically homeless. The term hashkafa means your religious outlook, how you view the world. Somebody who is homeless hashkafically means they don’t have an institution, they don’t have a lane, a clear lane where it’s like, I can be a card-carrying member of this institution, it’s going to take me through my entire life.

I think there was a time where we had that, or maybe it felt like we had that. I think what has changed most, and we have spoken about this on 18Forty, is this idea of feeling post-institutional, which is not about any individual community. It’s about the sense that our lives are never perfectly reflected in any institution. And what we are actually trying to do is teach people how to feel more comfortable in dialogue with their institutions, their community, and their own self.

We have the flexibility that we are not trying to ensure that one institution, one brick and mortar, whether it’s a university or a yeshiva or a high school, we’re not trying to reinforce one path. What we are trying to reinforce are the questions people ask, the journey through which people find comfort on their existing path, or, perhaps, need to find another trajectory. So what I’m really trying to do is not to get people to change communities.

One thing that I have learned from my own life and on 18Forty is that learning how to have the right amount of space between your individual life, your family life, and your institutional life is an art that too many people are failing at. Meaning people want their religious identity to line up like a straight arrow, where individually, our family, institutionally, we’re all exactly the same. And what I think I want to introduce to people is that it’s okay to affiliate one way, have your life in another way. You have your family over here. It doesn’t have to be a perfectly manicured, curated, just straight as an arrow.

You can have your own individual feelings that you carry and your life doesn’t have to map perfectly on any institution. What I’m really trying to tell people is that everyone, ultimately, is hashkafically homeless. It reminds me of one of my favorite essays that I’ve ever read in my entire life by David Foster Wallace. David Foster Wallace, who was a famous writer who took his own life, but he had this essay called “Laughing with Kafka.”

And the essay is about what it was like teaching the philosophy of Kafka to college students. And he said it was a disaster. It did not work. Why? College students do not want to learn Kafka. Why? Because Kafka is a type of humor that doesn’t have a punchline. It’s absurdity, but there’s no punchline, there’s no setup to it. And he says students spend their entire life banging on a door saying, let me in. I want to be inside, I want to come back home.

And what Kafka, and this is David Foster Wallace’s conception of it, teaches you is that you spend your whole life banging on a door, let me in, I want in, I want to feel whole. And at some point you realize the door opens outward. You’ve been inside the whole time. That our endless journey towards home is in fact our home. That this journey, this sense of alienation and difficulty and figuring out what life is and that sense of even destabilization—this is home, and that’s okay. And learning how to feel comfortable with that, learning how to make peace with that, learning how to nurture healthy relationships even within that, that’s our work. It’s the work of being alive, it’s the work of being a human being.

Malka Simkovich: So I think maybe one distinctive, not unique, distinctive aspect of our moment right now is changing conceptions of authority, because, and this goes back to what you said about living in an era in which rabbinic leadership is divided.

Tell me if you agree with this. The speed at which we are exposed to new ideas, new content, new information on all kinds of virtual and real platforms is diluting the authority of figures that maybe three or four generations ago would have been not competing with thousands of other voices. And I’m wondering whether you think that there’s a relationship between the speed of production of content and our changing conception and our changing relationship with rabbinic authorities, with rabbinic leaders.

And it makes me think especially of ChatGPT and other AI platforms that unless you ask them specifically to express doubt, they’re providing information in a way that is assertive, that is definitive, that is confident. And in that sense, it’s very different than the relationship or even the conversation that we’re having right now, where we can sort of intuit tone and confidence levels. But when we’re experiencing and when we’re asking for material that has been conveyed to us in authoritative assertive tones, then in that sort of same life routine, when we have a question that normally we would go to a rabbinic leader for, well, now we’re less motivated because we have these other sources of authority.

David Bashevkin: I think there are two things that have emerged that I would like to focus on. One is I actually think we’re getting back much more to our roots in terms of how authority was meant to work in the Jewish community.

Something that we actually spoke about on 18Forty on the series that you were a part of, which was the origins of Judaism, was this idea, and I’ll say it in a radical way, but then I’ll rephrase it, that there really is no such thing as rabbinic authority. That the authority that we have always had at our heart has been communal authority. Meaning, what preserves any sort of claim on anyone, halachically, is not that a rabbi said it. It’s never been that way. The fact that the Rambam said something does not have a claim on me just because he was the Rambam. It doesn’t. What gives someone a claim on me is that I am a part of a lived Jewish community that obligates themselves to that interpretation, to that approach to Torah. It is the community that obligates me, it is not the individual rabbi that obligates you.

And I think that notion of communal authority is actually very important and very healthy if you learn that what you really need to find is a community that has a standard that works for you. And different people want different things out of their community. That’s number one.

So I actually think the model, yes, you could go on to ChatGPT and ask, you know, basic detailed questions of Jewish law and you’ll get a fairly accurate answer. And I’m sure within a couple of months, if not a year, you’ll get a perfect answer. But that’s not really where halachic obligation comes from. It’s not having the right answer. Halachic obligation emerges from our communal identity, from being a part of Am Yisrael and Knesset Yisrael, the Jewish People. And different communities are fostering different interpretations of that, different modes of communal authority. That’s number one.

I want to say the second thing, which is, I think is even more important. And that is, I think the value of information is nosediving. I don’t think information is that valuable anymore. I tweeted this and I’m curious what you have to say about this. Like three weeks ago, I said, is there going to be such a thing as a PhD in 12 months from now? I have a PhD, you have a real PhD. I have a PhD that I like, literally, like last minute threw it in like a paper airplane.

Malka Simkovich: I highly doubt that, David.

David Bashevkin: It was, yeah. If COVID had not happened, I don’t think I would have ever finished my PhD. Just everyone was so tzaflagen. I’m like, now’s my time to get my doctoral committee together. They’re going to be so upside down, they’re not going to know what hit them.

But a PhD is a collection of information, a collection of information that we will be able with a set of prompts in 12 months to have a computer, I think, spit out a fairly impressive PhD. The value that I think is increasing exponentially is the value of experience, of feeling—what I said earlier, not just what you should feel, not just what you can feel, but what do you feel? I think for the first time, maybe not ever, but people are reacquainting themselves with that question. What do I feel right now? What’s inside of me? What am I carrying?

Malka Simkovich: I’m really still stuck on the PhD piece. Can I stop you here? In terms of the creativity and the requirement of original thought, and see, I have to defend academia because I gave my life to it, so I have to convince myself that there’s a value in it. But do you really think that AI can produce new creative ideas if it’s digesting massive amounts of material? Does that mean that it also has the ethical and moral discernment of a human being, or one day will have?

David Bashevkin: No. No.

Malka Simkovich: And if it does… So then doesn’t that just…

David Bashevkin: For one thing, you don’t need an ethical and moral discernment to write a PhD. I mean, come on now.

Malka Simkovich: No, but I’m just saying, if…

David Bashevkin: I have one.

Malka Simkovich: What are we afraid of? What are we afraid of when we talk about AI?

David Bashevkin: So that’s something else. I think what we are afraid of when we talk about AI is a question that I certainly have quoted many, many times from the book. This is from the greatest hits. There’s a book called The Most Human Human. The Most Human Human is a book written by Brian Christian, who wrote a book about participating in a Turing test. Do you know what a Turing test is? A Turing test is a test where you either speak to a computer or a person to find out who is real. So he did this Turing test, but he didn’t compete as a computer, he competed as a person, to be the undercover person who’s going to fool the judges that they’re talking to a computer rather than a person.

So he competes in this to be the most human human, to have text conversations with judges to see, can he fool them? Could it be absolutely clear that he is a human being? So he wrote a whole book about this process. After writing the book, he was asked in a question, I think in Paris Review or something, said, you went through this process, you tried to fool scientists, or not fool them, you tried to convince scientists via text that you are human. So you know a lot about, how do you display, how do you convey your humanity to somebody else? What is unique in your opinion about human beings? You went through this process, you wrote a book about it, what is unique?

And his response was so brilliant and hit me in a very real way. He said, scientists have been trying to answer this question for decades. They all try to fill in the sentence, the one thing that makes human beings unique is, fill in the blank. In 19, I think 87, Douglas Hofstadter wrote a book called Gödel, Escher, Bach. In that book, and he’s the father of the science of consciousness, he said, the one thing computers will never be able to do—this book won the Pulitzer Prize—beat us in chess. Said, never, they’ll never be able to do that. They beat us in chess, right? So we know that much.

So what was his response? His response was amazing. He said, human beings are the only animals that are anxious, that have angst over what makes them unique. We’re the only species that frets over our uniqueness. What is important about our lives? We’re all trying to find a story, a narrative, a meaning, a purpose to our lives. He is suggesting, a bat does not wake up and wonder, what is my purpose?

Malka Simkovich: A cognition.

David Bashevkin: Yeah. What he is talking about, human beings are unique, we are worried about what makes us unique. If you were to ask me, what is AI and in a positive way, what is the question it is posing us? It is posing us the question of where’s our humanity now? For we’ve spent a thousand years where to be human was to be scholar, was to have access to information, to be able to retain information. As the value of information goes down, I think we have this underlying angst. What’s going to make us unique now?

And it’s an angst that people have professionally in very real ways. The economy is shifting really, really quickly. It’s angst that people have, I think, romantically. When you have access to so much information, this is Barry Schwartz who writes this in his book Paradox of Choice, being able to make a choice is more difficult the more options you have.

It’s why in the Hebrew, can I say one piece of Torah? I’m sorry. I’m going to say one piece of Torah. Nobody gets stressed out. But it’s always moved me that the word for choice in Hebrew, bachar, bechira, is the very same words as charav, churban, which means to destroy. Anytime we are deciding, it comes from the same root word as homicide and suicide, we are essentially killing off a possibility. We’re saying the future is only going to be in this direction. Making decisions is especially painful right now in this moment. What are you doing for your career? What does every college kid dread? So what are you going to do with that? What are you majoring in? What are you going to… what is that a good job for a nice Jewish boy?

So it affects us professionally, it affects us in our relationships, romantically, dating. I mean, I don’t know if you have kids yet who are dating. I know this from my own students. It’s a real nightmare for people. It’s a real nightmare to be able to make that decision to say this is the person I’m going to build my life with when we have access to so many people. You just—at the drop of a phone. And then ultimately religiously. We’re faced with new questions religiously. How are we going to build our lives? What is the role that Judaism is going to play in our lives? What’s Judaism going to look like in 10 years from now? That’s the question.

Malka Simkovich: We have so many choices and we have endless access to infinite, almost, information. But in this Jewish moment, it can also feel, I think, like the world is closing in on us. And in some ways, and just to bring this back to the contemporary Jewish experience, we don’t know what’s going to be for the Jewish People. It almost feels like we’re at the top of a mountain and we’re approaching the top of a cliff and we can’t see over. We’re in a historic moment, we’re in a pivotal moment, but we don’t understand it. We don’t know what’s on the other side for us.

When we talk about choices, I do have two teenagers who’ve just finished high school, and they don’t feel like they have any choices. The conversation that we had with them was essentially if you’re not going to go to Yeshiva University, are you making aliyah? Now, that might not be legitimate and I know that there are many wonderful campuses out there who support Jewish students and we don’t have to get into the brass tacks of that, but that was our family conversation. And I think that many young people are feeling maybe more limited than we may have felt 15, 20 years ago.

I don’t know that this young generation feels that the world is their oyster. I think that we have two realities in tension. One is that they have access to thousands of TikTok reels a day. They can ask any question of AI and get information, but in terms of their own path, I don’t know that they feel personal agency, that they feel empowered, that they feel that they can make whatever choices they want.

And by the way, this is something that you’ve spoken about many times, David, there’s also that economic piece. I think especially for young men, but also for young women, if they want to be in a particular community, they don’t know that they can pursue a master’s or a PhD in dance or music or in the humanities. That’s a luxury degree. A PhD in the humanities is a luxury degree. There’s a lot of pressure, and so that really narrows the choices professionally and narrows the choices geographically.

And so I think that these two realities on the one hand, they can access the universe right now. They can watch a video that was taken five seconds ago in Singapore, but they can’t necessarily tap into the freedom that they’re experiencing through their screen.

David Bashevkin: I could only talk from myself, but I was sharing this with somebody earlier literally today from an article that I wrote pre-2020, pre-18Forty where I spoke about this idea of the Bermuda Triangle of Jewish life, where you know, you have this idea of the Bermuda Triangle off the coast of Florida and Bermuda and the islands, where a lot of planes would get lost because of weather and tropical storms.

I think we have a new Bermuda Triangle, at least within the Orthodox and Orthodox-adjacent community. And that Bermuda triangle is because there is so much that we want perfect and we know how difficult it is to maintain our lives. And we love our lives. We have an incredible community, but we’re losing a lot of planes. Where are we losing them? In this Bermuda Triangle. That is your religious identity, your professional identity, and your romantic identity. And that we want people to have all three of these figured out by the time that they’re 21.

I teach at Yeshiva University. I love Yeshiva University. You see the students there, the angst that they feel about marriage, about their lives and their careers. I don’t know if it was always like this. My impression is it was not. My father and myself are both graduates of Yeshiva University. Something is more intense right now in our community, this impatience, this sense of, I don’t want to paint in too broad of a stroke, but everyone is just trying to find something that gives them some measure of stability. But I feel like when everyone is retreating to the points of comfort, stability, and security, we’re going to be left collectively as a community without a vision forward.

Malka Simkovich: I’m told that we have to wrap up in a few minutes, so I want to ask you, what’s your best case scenario? If you could put out a public call to action to all of world Jewry, what would you want them to be doing besides listening to 18Forty? What’s the call to action to the Jewish People? How do we maintain cohesion, especially in this new era of new relationships with rabbinic authorities and communal leadership? How do we stay together? What’s your call to action?

David Bashevkin: I think we spent the last 75 years on American soil, where each community and each denomination and all of the entire tapestry of North American Jewry, spent a lot of time investing in ourselves and our community. Building JCCs, building temples, building … I think the greatest miracle of the last 100 years is the day school system, which is absolutely incredible. We spent the last 75 years investing in all of this.

It has come at a very real cost and a deliberate cost. The deliberate cost is that we have not really been in dialogue communally, different types of Jews in almost a century, which is very unusual. That is an aberration. And you could correct me as a historian, how homogeneous it has become in some corners of the Jewish community.

And what I think now we have this moment where people who have been a part of building Jewish community, who have been a part of bringing Yiddishkeit into their lives, sometimes successfully and even sometimes messing up. The call to action right now, I think, is that we should be beginning a conversation where wherever anybody, whatever neck of the woods anybody came from, we should start a global conversation where we learn about one another, where we learn about what motivates one another. I mean the entire Jewish world.

That is what I mean when I talk about a beis medrash for the study of the Jewish People. What we have forgotten is literally how to talk to each other. Pshuto k’mashmao, literally. We have forgotten how to talk to each other. I know this because anytime I talk to somebody and it upsets them to such a point, I’ll get angry calls in a second, just like, how could you, how dare you, what? And I think we have lost our ability to engage in conversation, whether it’s the zeitgeist or politics or whatever it is.

And what I think this moment calls for is rich, serious conversation about religion. It frustrates me to no end that number one, the Jewish community, I think is making all the wrong choices all again. We should continue with strength and with optimism. It worries me if we lean too heavily into the trauma of October 7, and we leaned very heavily into the trauma of the Holocaust, at some point, someone needs to get up and begin a global conversation about a vision of Judaism that can reach beyond any particular community, and really start bringing people to articulate that vision. I think Chabad does a tremendous job of that, and they’ll do that in their communities. I think the Sefardic community, I was telling somebody earlier, does a tremendous job of that. But there are large swaths of the community that we need to have a conversation.

One of the real changes that I had over the last, I would say, five years through running 18Forty was I used to always think … because I came from a family where most Bashevkins in the world are not religious. In a generation, most Bashevkins in the world are not going to be Jewish. Within a generation. That’s my guess, a generation or two. And there are a lot of Bashevkins in the world. There’s a Bashevkin on the world soccer team. That’s a true story. You can look him up. Isaac Bashevkin, distant relative. And Natan Bashevkin. Always shout out to Natan Bashevkin. He won Survivor Israel. That’s a big deal. That’s a big deal. Because winning Survivor America is not a big deal. That just means that you can just walk a flight of steps without going out of breath. But winning Survivor Israel, where actually, like, every citizen could, like, survive things, it’s impressive.

Anyways, I think that’s what this moment calls for. And the beauty of what I’m able to do on 18Forty, what we’re able to do, and what this room is, somebody came over to me before. I was looking at who the room is. There are people that are from the Hamptons, they’re from Boro Park. In this very room, the amount of stories and backgrounds, and we have Klal Yisrael right here. We have it right here.

Let me say one thing. You know, I was invited to speak by someone who’s here at a rabbinic gathering of rabbis talking amongst each other about how to reach other Jews. And they were talking about burnout in the religious community, why people get burnt out. They were talking to a group of rabbis, and they had somebody come in and do like a role play for the rabbis to like teach them, like what would it be like if, you know, I’m 35 years old, I’m in real estate, I stopped learning Daf Yomi, whatever. And the rabbis had to pitch them.

And it was my turn to do this and I was maybe a little blunt. I didn’t say it. I was definitely thinking it. I’m like, this is absurd. This is ridiculous. We need to learn how to access those feelings right here. Meaning in this very room, the feelings about Jewish identity. We’re not going to do it. If I pass around a microphone and just start a conversation, how does being Jewish make you feel? And teaching people how to unpack their baggage in healthy ways, what triggers them. We’re never going to be able to have achdus by talking about achdus.

The only way to have Jewish unity is to be willing to be made uncomfortable. If you are not willing to be made uncomfortable, you are not going to be a part of the project of unifying the Jewish People. The project of unifying the Jewish People means walking down a road where you’re going to be made uncomfortable. And we need people, that’s what we need, we need people who are willing to be uncomfortable on behalf of the Jewish People. And number two, people who are willing to learn multiple languages of Judaism, multiple languages of how to interact and how to bring Yiddishkeit to multiple different audiences, people who are bilingual.

Which is why—somebody asked me, why did you have Malka Simkovich of all of your former guests? You’re the most amazing. That was the answer I gave them. You’re the most amazing we had. But I said, here’s what strikes me about Malka, is that you are multilingual on many different levels. It’s what really struck me. You are both academic and you can talk to a popular audience. You were raised in the yeshiva world, you’re very familiar with the Modern Orthodox world, and the academic world. You are able to see and hold many. And at the heart of the revolution that I’ve gone through since 18Forty, and I mean this so seriously, is our conversation. And I want to say why. Can I say why?

Malka Simkovich: Do it.

David Bashevkin: We had a conversation where we were talking about the rationality of Judaism, and why should somebody believe in this? And you said you like to reframe the conversation. Instead of being about how do we know, you know, the Torah, and how do we know it’s true, and it’s real and handed down. Here’s one thing we definitely know and here should be our starting point: God and the Jewish People. We know, if you start with the Jewish People, we know tangibly what we’ve been through. We know tangibly what we’ve gone through. What we are trying to do, what I think this revolution can be about, is restoring that spiritual energy, excitement, and ambition that has always been a part of the Jewish People. The sincerity of the Jewish People, and opening it up to all participate and gather to talk not about politics, not about antisemitism, not about Israel, to talk about Yiddishkeit, talk about our commitments and our lives.

Malka Simkovich: Wow. I think that your project is a deeply rabbinic project because I think that the rabbis were trying to achieve this in the wake of four or five centuries in which Judaism was, I wouldn’t say deeply divided or plagued by sectarianism, but certainly there was a concern that in the wake of the fall of the temple, of the Beit HaMikdash, there wouldn’t be a cohesive, practicable, normative Judaism that could accommodate the dispersion, the geographic dispersion, the different interests, the different cultures. And the rabbis achieved that, and they did it with brilliance, they did it with sensitivity. They did it in the liturgy, and we could talk another time about the Amidah, the heart of Jewish liturgy, I think is a prayer that tries to overcome sectarian divide. So I think that your project…

David Bashevkin: One more time?

Malka Simkovich: I don’t know what I just said.

David Bashevkin: That liturgy is a prayer that tries to overcome…

Malka Simkovich: The Amidah.

David Bashevkin: The Amidah.

Malka Simkovich: That we pray…

David Bashevkin: That we pray.

Malka Simkovich: … that uses the phrase Am Yisrael over and over and over. And if you compare it with a version that was found at the Cairo Genizah, which preserves a much earlier version, so the rabbinic version that we pray…

David Bashevkin: Yeah.

Malka Simkovich: … when you compare it to the earlier version, is an anti-sectarian prayer. The changes that the Rabbis made to the Second Temple version of the Shmoneh Esrei, of the Amidah, are changes that insert over and over the phrase Am Yisrael. And if you read the closing prayer Sim Shalom, bestow peace, bestow brotherly love, fraternal love among all the people of Israel. What that prayer is for is asking God for the grace and the inspiration to overcome the pettiness, the divide, the things that are unimportant, the things that separate us, and to overcome that and really to stay together in the confidence and in the knowledge that God gave each one of us a covenant and desires a relationship with us all.

Sruli Fruchter: And on that note … is that God? And on that note, we’re going to take some audience Q&A to expand the conversation. You don’t have to wait for the listener feedback episode. So just raise your hand, we’ll have some of our staff come up and hand you the mic. I see someone in the back. You’ll go number one.

Ezra Ratner: My name is Ezra Ratner. These are both of my teachers here.

I’ve been profoundly impacted by both of you in classes and both of you when you speak to each other. And I’m interested in how your three conversations with each other have impacted both of you, and which one do you find the most impactful of the three?

Malka Simkovich: It’s a great question.

David Bashevkin: The first conversation where you reoriented and said the starting point educationally should be about the Jewish People. That was an eye-opening shift for me that led me to even ask the question, what does it mean to be an expert in the Jewish People? What would it mean to study the Jewish People? There’s this idea from the Ramchal, who’s a great Kabbalist, Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, who says that Torah, Yisrael, veKudsha Brich Hu—God, the Torah, and the Jewish People are all one.

So I know what it means to be an expert in God. That’s prayer, that’s meditation, that’s prophecy. I know what it means to be an expert in Torah. That’s a Talmid Chacham. What is an expert in the Jewish People? What is that? What is that called? What is that consciousness called? And that I think grew out from our conversation … my obsession, my love, my starting point of the Jewish People began with us.

Malka Simkovich: Wow. I have a different answer, but it’s also the first episode because after that episode, David, I wanted to call you and tell you to cancel it, to not post it, because I felt totally overexposed. It was the first time that I’d ever gotten personal in a public way. And when you went forward with it, with some editing, and it was posted, it was a turning point for me because I realized that what you do, and the reason why you do it effectively, and the reason why you do it well, you do in your full self, meaning you’re bringing your full self into your work. And that is not something that academics are trained or encouraged to do. They’re told to bifurcate, and especially as I would say, someone who lives in the Orthodox world and is working on the Hebrew Bible and the history of antiquity, that was my intuition is to separate. And then from our conversation and your questions about belief, and this goes back to my original question to you in this conversation right now about surprise, my personal surprise when I was in conversation with you was that I can bring a cohesive … I can bring my full self into my work. And that wasn’t something that I had faced, I would say, in a very honest way before that conversation.

David Bashevkin: I want to start, write an essay on the Kübler-Ross five stages of grief that you appeared on a podcast, because it happens very slowly. It first starts with, like, a text message like, how did that come out? Do you think it was good? Then the next morning it’s like, do you mind if you send me the draft then I could relisten to it? Then the third email is like, you know what? I don’t think you should post this at all.

Malka Simkovich: That’s right.

David Bashevkin: Emergency conversation.

Malka Simkovich: Yeah. And then it all works out in the end and David is always right.

Sruli Fruchter: And our next question, all the way in the far right.

Speaker: After October 7, the Jewish People seemed to be really united and over the last, I guess, two years, it seems to have faded and now we’re splintering again. And that was a pretty traumatic experience. What do you see as the thing that actually brings us all together in a more permanent way?

David Bashevkin: Right after September 11, I know. I know.

Malka Simkovich: He’s getting there.

David Bashevkin: I’ll get there. Right after September 11th, Maureen Dowd wrote an op-ed in the New York Times that had a really big impact on me where she was talking about … I’m sure you remember this, I remember this, every single home had an American flag outside. It was everywhere. And she said, and it was a great line, she said, our obsession with how much we’ve changed is indicative of how much we’ve stayed the same. I’m always suspicious of everyone, like, too quick, Kumbaya, we won, you know, beyachad nenatzeach, it was a great slogan, it was definitely appropriate for that moment. I think now we’re so deep into it that I think a lot of the divisiveness has reemerged and I think the answer to it is what I said earlier.

Achdus will never be achieved by people who only want the good feelings, who only want the joy of unity. If you’ve ever actually made a deep friendship, if you’ve ever had a real relationship in your life, there’s no way to cultivate a relationship like that when you only want the good times together, when you only want to be, you know, like lovely and wonderful and loving together. What really, I think, shapes our community’s achdus is the willingness to at least for a moment be uncomfortable and like, be honest and be sincere. There’s something very painful about vulnerability. It requires a great deal of strength and courage and realignment, but I think as a community, we have to be willing to be vulnerable in that way.

Malka Simkovich: Great answer.

Sruli Fruchter: Alright, and our next question.

Speaker: Hi. I don’t know if it’s a historical thing that, let’s say, right now we’re trying to group ourselves, let’s say, not by halacha, but by our communal norms. So, let’s say where the last few hundred years where denominations became a thing, but would you say that historically, that wasn’t the binding part of what brought us together and that like we kind of are in this world where you’re either in or out based off halacha, and now maybe it’s you’re in or out based off other communal norms. Like, how will that necessarily bring us into the future? Or maybe that’s the way it always was and it was kind of maybe a blip once the denominations became a thing that halacha was there, you’re in or out.

Malka Simkovich: I’m not sure I understand the question. Are you asking whether normative halacha has always been the binding agent that brought Jews who are observant together into community?

Speaker: Well then saying maybe we’re trying the project here that that’s not necessarily the thing that should be going forward and maybe that … I’m still formulating it, you know, let’s pretend it’s a podcast or something, but that’s the general question I guess.

David Bashevkin: If you study those Jews in the early years after the diaspora. If you’re living, you know, where you have people who in their living memory, there was a temple standing. And now they’re building a community in the diaspora. What do they think connects them to Jews around the world?

Malka Simkovich: This is a huge question and there’s thousands of pages that survived in 2025 from that era. You can only imagine how many more were written that have not survived. Jews ask this question, what keeps us together? Is it the Temple? Is it Jerusalem? Is it Judea? Is it the practices? And of course, you get different answers depending on where you’re living. And Jews outside the Land of Israel want to say, generally, no, it’s not the Temple. We’re going to send our checks and we’re going to financially support the Temple, but it’s not. It’s the practices and it’s the Torah more than anything. It’s the shared stories, the shared experiences. What brings us together at the Seder table when we see relatives for, you know, once a year maybe? It’s the shared past, the memories.

But unfortunately, what we see when we study that era, and I think what’s happening now, is that crisis brings Jews together. And that’s always been the case. In 38 CE, there were anti-Jewish pogroms in the city of Alexandria, which was considered to be the most progressive city in the Hellenistic world. And the Jews there who were very affluent and very integrated were reeling, they were traumatized. And they chose five elite, powerful, influential Jews to go to Rome to appeal to Gaius Caligula to protect the Jews. That was a moment of unity in Ptolemaic Egypt that hadn’t really existed for a hundred years beforehand and never existed again.

So is that the story that we want? Like David is saying, should we only be waiting for emergencies to come together? No, I think we could all agree that that’s not ideal. And yet that’s the pattern that we see. And I guess the question is, how do we get ahead of it by being proactive and saying, all right, before the next terrible thing happens, how do we build communities that cross those denominational lines and maybe soften the boundaries just a little bit so that we can be in relationship with one another. I don’t know that that has happened successfully before.

David Bashevkin: Can I add one thing? It’s just interesting that you said about consciously coming together. There’s a book about Jewish continuity that was written by somebody named Rabbi Abraham Cooperman, I believe. And in his book, he makes the argument that the first time in Modern Jewish history, and you could take the argument or leave it, that the Jewish community consciously got together to be unified, that we would say, look, we’re different, we don’t agree, that different denominations came together for the purpose of unity. When was the first time that that happened? 1840 after the Damascus affair. That’s what he says. True story.