AI & Halacha: On Transparency and Accountability

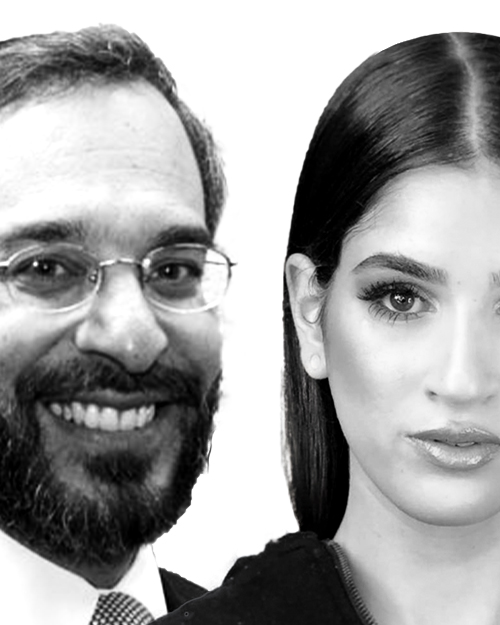

Rabbi Gil Student speaks with Rabbi Aryeh Klapper and Sofer.ai CEO Zach Fish about how AI is reshaping questions of Jewish practice.

Summary

This series is sponsored by American Security Foundation.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, Rabbi Gil Student speaks with Rabbi Aryeh Klapper and Sofer.ai CEO Zach Fish about how AI is reshaping questions of Jewish practice.

As AI simulates more and more human activities, we can’t help but wonder: Will AI replace rabbis? In this episode we discuss:

—What happens when centuries of halachic process meet a radically new technology?

—Can AI responsibly or accurately answer halachic questions?

—What are the ethical responsibilities of those who build and deploy AI?

Tune in for a conversation about the possibilities and limits of our digital tools.

Panel begins at 8:36.

Rabbi Gil Student is the director of Jewish media publications and editorial communications at the Orthodox Union.

Rabbi Aryeh Klapper is the dean of the Center for Modern Torah Leadership, the author of Divine Will and Human Experience, and a frequent writer on the ethical dimensions of Jewish law.

Zach Fish is the creator of Sofer.ai, a cutting-edge transcription service designed for the Jewish community.

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Bashevkin: Hi friends and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin and this month we’re continuing our exploration of AI. Thank you so much to our partners at the American Security Fund for their generous support and guidance on this important subject. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18Forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.There is no question that when technology evolves, it also has an effect on the very experience of Yiddishkeit and Judaism itself.

I think the person who noted this in the most clear and obvious way is Professor Haym Soloveitchik in his article “Rupture and Reconstruction.” He talks about how modernity and acculturation to the United States of America really affected the way that we relate and cultivate Jewish law known as Halacha. We’ve had Haym Soloveitchik on twice on 18Forty, but his essential argument is that Halacha goes from being something mimetic, which is what it was pre-war in the shtetl. It was imitative, mimetic, like from the word meme, to imitate.

Halacha was very imitative. That was the Yiddishkeit of my bubby, of my zayde. They didn’t know all the details, but they did, they kept a kosher home based on what their parents did. And that is the way Halacha was perpetuated really through most of European Jewish history.

However, on American soil post World War II, we saw a move back to text-based authority to really try to maximize the amount of opinions, how things can be done, leniencies, stringencies, and it became much more detailed, and in some ways it became more stringent. Whether or not you agree with the phenomenon that Haym Soloveitchik talks about, I think there’s no question that the advent of the internet and even more so in this moment that we are in in AI is affecting the way that we relate to Halacha itself, the way that we relate to Jewish law. We have so much more access to so many more opinions, to so many more minority opinions, stringent opinions. Access is going to change what the actual practice is going to do. My favorite pastime is exploring Jewish WhatsApp groups.

So there are a lot of WhatsApp groups, and you don’t have to be Jewish to have a WhatsApp account, but WhatsApp groups play a pivotal role within the Jewish community, whether it’s WhatsApp groups about bringing things to Israel or WhatsApp groups about different niche interests in Judaism, whether it’s Jewish books or etc, etc, any of those things. But one of the things that I think is really fascinating are Halacha WhatsApp groups, WhatsApp groups where you could ask in real time a rabbi who’s the administrator of the group all of your Halachic questions. I belong to a bunch of these. My favorite one is obviously known as the BMW Halachic chat, the Beis Medrash of Woodmere Halachic chat, and I am known only for posting inappropriate and irrelevant things into the WhatsApp group.

Not inappropriate, but I’m the one who always calls people out when they delete things or I’m mischievous in the WhatsApp group. I’m not really asking my formal Halachic questions, but I’m looking around and seeing what are the types of questions people ask. And I think the advent of AI is going to change this even more.As we see now, you can ask basic Halachic questions, even somewhat sophisticated ones, and depending on the AI chatbot, you can really get sometimes some pretty good answers. I think right now you still have to double check, but it leaves the question, is AI going to replace rabbis? And I think on this issue, if you’ll allow me to kind of present a spoiler of sorts, it is something that I’ve discussed before, but I think even this question comes from a severe misunderstanding of what even the role of a rabbi is.

I’ve said this many times before, and I’ve written an article about it. I always write an article at the end of every tractate of Talmud along with Daf Yomi for Tablet magazine, and the article I wrote on tractate Horayos, which is all about Jewish leadership and Jewish law, I made this point which I originally made on social media, and I’m going to read directly off of a social media thread that I have shared on multiple occasions, especially during the last election cycle when you saw there was this video that was shared that was just people saying, Hi Rabbi, Hi Rabbi, Hi Rabbi. And then afterwards, they said who we think you should vote for. It was not the candidate that much of the Jewish community was supporting, but I don’t think need to get into that election right now.

What I think is really interesting is what is a rabbi actually in our history, in our mesorah, in our tradition. A rabbi is not somebody who has access to the most information. Yes, there is a basis of knowledge that rabbis have traditionally had, but that is not where their authority derives. A diploma doesn’t make someone a rabbi.

Jewish leadership is about responsibility and not a credential. Rabbis are judged, and this is true throughout history, based on the community and the students they cultivate. When someone calls themselves a rabbi, and I beg people to remember this, your first question should always be, in whose eyes? The authority of a rabbi does not derive because they are a rabbi or because of the title rabbi or a diploma rabbi. The authority of a rabbi derives from the community that they lead.

We don’t even know where or if some of the most important rabbis in Jewish history were ordained. I don’t even know some rabbis if they got rabbinic ordination. Jewish tradition is not shaped by rabbinic authority, but I believe the Jewish community and what they preserve through the generations. Yiddishkeit is perpetuated by students, not by teachers.

It’s who the students choose to continue. That we have a Rambam is not just based on the magisterial work and authority of the Rambam. It’s not because the Rambam commanded us, you need to study my works. It is because his students and later generations invested authority into the work of the Rambam.

Jewish tradition is shaped not by the rabbis, but by the communities that they lead and preserve their works. And that is why I don’t think AI will ever be able to produce or become, so to speak, a rabbi, because the authority of a rabbi is a product not of any information or not of any diploma, but the lived community that they are able to create. But without future spoilers, and there is so much more to say about this, we had an absolutely fascinating conversation at our AI conference that we have been pulling from and sharing with our audience. And this was a session that we did about whether AI will ever have halachic authority, could ever be like a posek, a halachic decider who could then, you know, be in charge, so to speak.

And my answer was and is always an emphatic no. But interestingly enough, I was not on this panel, nor did I moderate this panel. This was a panel that was moderated by a dear friend of the 18Forty podcast, my friend Rabbi Gil Student. And he was in conversation with two really incredible thinkers.

One is Zach Fish from Sofer AI. If you’re not familiar yet with the work of Sofer AI, they are doing some of the most innovative work in wedding AI to the work of translation, distillation of Torah ideas. We actually use them ourselves to create 18Forty transcripts. You can imagine normal transcribing services have a pretty hard time with 18Forty because of all of the gibberish that I use, and the words that I mispronounce and the Yiddishisms, etcetera, etcetera.

And we use his programs. Sofer AI for a tremendous amount of our work. And we also had a phenomenal thinker, someone who I just had the privilege to meet, and that is Rabbi Aryeh Klapper. Rabbi Aryeh Klapper is really an innovative thinker, goes back many, many years.

He runs the Center for Modern Torah Leadership in Boston. He is a phenomenal thinker, a really thoughtful reflector on what Halacha and Jewish law is all about, which is why I am so excited to introduce our panel moderated by Rabbi Gil Student with Zach Fish and Aryeh Klapper.

Gil Student: My name is Gil Student. I’m the director of Jewish Media publications and editorial communications at the Orthodox Union.

I work very closely with the 18Fortyteam, so I know how hard, how much work and how much thought it was put into this conference. I thank them very much for their work. To my left here is Rabbi Aryeh Klapper, an old friend of mine. Rabbi Klapper is the dean of the Center for Modern Torah leadership, the author of Divine Will and Human Experience, explorations of the halachic system and its values.

Rabbi Klapper is a frequent writer on ethical dimensions of Jewish law, and to his left is Zach Fish. Zach is the creator of Sofer.ai, which is a cutting edge transcription plus website and app for Torah use. He’s really on the cutting edge, and he works directly with Torah organizations and rabbis. So, today’s discussion, transparency, responsibility, accountability, the posek and AI.

Let me just pause and say a posek is a rabbi who decides on issues of Jewish law. So we’re going to talk about, I think what is a pressing question, and what happens when centuries or millennia of halachic process encounter a radically new tool? So AI raises issues of authenticity, of reliability, access, responsibility, authority. So we’re not going to be settling any of these difficult issues, but hopefully we can start the conversation that rabbis and lay people are going to be having over the next few years. There’s a great book by Salman Khan of the online Khan Academy.

I saw in there a very interesting, the beginning of one of his chapters. He says when a hot new technology like GPT-4 comes out, it is important not to use it simply because it is cool. We have to think about what important problems the technology might be able to solve. So before we even begin to talk about authority and AI and psak halacha, the religious decisions, my question to my two co-panelists here is, is there a problem with psak today that AI can fix, or is it just a cool new technology? Rabbi Klapper, you want to start?

Aryeh Klapper: The only thing I’m actually aware of of a problem that AI per se could solve, there are potential issues in terms of inundation of really popular poskim with repetitive questions that I imagine you could alleviate burdens in that way, but as a substantive issue in terms of psak, I’m not aware of anything.

There might be opportunities, and I can talk about one of those opportunities I think as we go on, but I don’t think there’s a substantive problem that there’s something we don’t know how to do yet that AI solves.

Gil Student: So you’re speaking as a rabbi involved in psak. Zach, you’re a lay person involved in psak. What are you seeing from the other end?

Zach Fish: I don’t think 1840 brought me here as a halachic posek and I don’t think they brought me here as a philosopher and an intellectual.

I’m really going to approach it from the engineer perspective because that’s what I do. And I don’t think from that perspective that AI is the right tool to help in psak itself, to pasken, to take that role. I think what AI does really well is could help in a lot of parts of the process of knowledge retrieval and making processes in that process more efficient. So in that way, it could help in psak, but I don’t think it is a tool for psak, to go to for psak.

And I imagine we’re going to talk more about why that is. That’s what I would say about that.

Gil Student: So it sounds like we’re saying that it’s just a cool new technology.

Zach Fish: No, I think it’s extremely helpful.

It is transformative and it helps people do so much. But I think you have to have the right mindset of how to use the tool. I think some people come to AI as an authoritative type of being or thing, and you’re coming to it as almost like you’re a client of it. Like, do this for me, right? And like you do it and then I’m asking you to do work for me and you do it for me.

I think you have to approach it as you’re its manager. It is a tool that you are in charge of, that you are fully aware of how it works and you’re aware of its strengths and weaknesses. And once you could realize that, you could use this tool to make what you’re doing so much more efficient, so much better, find new creative ideas that you didn’t think about. But there are places where there are limitations in the tool and you have to be aware of that, and one of them is in psak.

I don’t know if you want to get to why I think that now or

Gil Student: No, I want to push back on both of you because I completely disagree. The nature of the Jewish community, the Orthodox Jewish community that observes so many rituals, so many laws, and we have so many law books, and it’s 2,000 years of development since the Mishna and the Gemara, and so many different opinions, people don’t always know what to do. You’re raised as a child and you kind of learn by rote and through school what to do in most situations, but in life you’re going to face a lot of different situations and questions come up. Used to be you had to ask the rabbi.

Then came the internet. Actually no, let me take a step back. Let’s talk about halachic precedence. Then came the Shulchan Aruch, or then came the Rambam, or even before that, then came the writing of the Oral Torah.

It used to be all oral, and you needed a rabbi, and you needed to remember things, and you needed to have people with great memories. Then they wrote down the Mishna, then they wrote down the Talmud. Then they wrote down the Mishneh Torah, then the Shulchan Aruch didn’t come from nowhere, there were multiple steps till you got to Shulchan Aruch. And then even beyond that, then you had the Chayei Adam, you have the Mishnah Berurah, you have the Kaf HaChaim.

There have been many tools throughout the generations for people to just look up the answer, where people can, it’s not intended to, where people can just look up the answer and not go to their rabbi. And I see AI just as part of that continuum from Rabbi Google, which we all know people Google most of their questions nowadays, they don’t go to their rabbi. And AI I think is going to be the next step, not because there’s a problem that AI can solve, but because it’s just people are lazy. I myself normally daven at the shtiebel at the corner of my block, don’t go to my normal synagogue four blocks away, ’cause I’m too lazy.

That applies to everything in life. We’re just lazy and AI is there, so we’re going to use it. And Google is really bad at paskening shailos. You Google something, you get a whole bunch of websites and you just click on it, people do it differently.

AI is, at least right now, maybe better. Maybe it’s a little better. Moshe certainly thinks it’s better. I don’t think it’s solving a problem, but I think it’s a reality we’re going to have to live with just because people are lazy, and maybe lazy is a condescending term and really it’s just people are more equipped.

Zach Fish: I guess we could define what psak is on another level deeper. I actually got this from a Torah Musings article, which is Rabbi Student’s blog and it’s fantastic, fantastic articles there, and I believe you have an article there, kind of differentiating what is like real psak and what is just technical reference, which is something the Maharam MiRotenburg kind of distinguished between. I believe it’s paskened by the Shach in Yoreh Deah, that there’s two types of like what’s psak. If there’s an answer in a book and you’re just showing here’s what it says in the book, that’s more of like a technical reference.

And like colloquially, we’ll call that psak, but maybe that’s not real like halachic psak on the same level. What I was referring to is can AI pasken is kind of the more higher level of psak where you need like this reflection and analysis and to abstract the idea from here, abstract the idea from here, bring them together to compare is this similar to that. That I think there are struggles. For the technical reference, and this is what it was referencing and how it could be helpful.

I love using AI tools to find things and to go through Google and to find the relevant articles. I personally have in all my set prompts, I want links. I don’t want the LLM to summarize and tell me what it says and what it thinks, because there are problems of hallucination, how it interprets it. But what it’s so good at is instead of like going to Google, saying, “Find me articles that talk about this.

Has anyone talked about this specific case?” And it could go through and find all the cases for you. And then you could go look at it and that’s an amazingly efficient way of getting information that you need and getting answers, instead of going through the OU and CRC and all that and going finding it. Now you can ask the AI to find who talks about this case that I have in my life. Is this kosher? Is this not kosher? What bracha do I make here? What do I do in this situation? You go to the AI, it searches the internet for you, it searches all the publicly available things for you and then it finds the reference for you.

But what I would like to distinguish is, is I think there’s like two layers to this. There’s a layer of what the LLM says and the LLM is finding. I very much like the LLM finding these things because it has a very good understanding. But when it shows it to me, I either want the reference itself or there’s an approach that I have with clients I work with in the Torah space called deterministic quoting, where it will find the source for me, but I do not let the LLM even summarize or tell me what it is.

Instead, I ask it in the back end to say, “Hey, tell me what the most relevant piece from this source is.” It’ll tell me the most relevant piece, then deterministically, meaning not using an LLM, because LLMs no matter what you do, there’s a chance that they hallucinate or misinterpret. So I tell it deterministically, I find the match of what the LLM thinks the most relevant part is, pull that from the article, pull that from the source, pull that from the core, and this text that I’m now showing is not LLM generated. It is the exact word for word, character for character, space for space, the wrong apostrophe there. If it has a mistake in it, the mistake stays.

It’s exactly from the actual source. And now we’re leveraging, “Oh, the LLM is doing great at searching and understanding and using what it’s really good at.” But then I could use non-AI. I could use deterministic coding to see the source, expose it. And the AI could also weave a very nice article for you and say, “Here it talks about this, here it talks about this.

This deals with this issue,” but the actual source that you are looking at is not AI generated. And I think that is like a distinction of like the technical reference of AI being really good at referencing and finding references for you versus it itself generating answers or it itself kind of extrapolating from sources. And there, if you approach it as like, give me psak in here, I don’t think it’s the right tool. For what you’re saying, most basic questions, find me the answer to this, I think it’s fantastic.

Gil Student: First of all, thank you for quoting my essay which is in my book, Articles of Faith: Traditional Jewish Belief in the Internet Era. Rabbi Bashevkin encourages me to push product. So, what you mentioned though is a philosophical discussion we’re having at the OU. We’re about to start beta testing an app that we built and part of that app built on our database of hundreds of thousands of hours of shiurim, of lectures, we have a chatbot.

And I wanted the chatbot to be exactly what you just said, deterministic. Just get a quote in a shiur. You know, you ask a question, “What time can we daven Mincha until then?” Quote the different lectures with a link to it, have the AI add nothing. The feedback we got was nobody wants that kind of chatbot.

People want an answer. You can then push them to the lectures and say to learn more, go here, you know, like the Google AI overview with links and things like that. You can try to push them in that direction, but the bottom line, you’re hiking in the forest and it’s the sun is setting, you want to know, can I daven Mincha now or not? People want an answer. There is somewhere in between, there’s a whole spectrum of possible ways to do a chatbot, but that’s something that we’ve been thinking about.

And in terms of pushing product, the app is called Ohrbit, O H R B I T. Look for it soon in the app store once we’re done with beta testing. Push product, sorry.

Zach Fish: Can we be beta testers?

Question: Let us know as well.

Gil Student: If you want to be a beta tester, please let me or Rabbi Taylor there know. We’re very anxious to hear what people have to say. Please.

Aryeh Klapper: Okay, I don’t have a product to push.

I’ll start with that. It’s a pity, I’ll remember for next time to bring t-shirts. I don’t think there’s any basis for controversy about information retrieval. I like to say like I’m the first generation of acknowledged Bar-Ilan responsa scholars.

You know, at some point in my life I switched from memorizing location of words on a page with page numbers to memorizing search strings. And that gives me really powerful tools during the week and makes me often the wrong person to ask shaylos to on Shabbos. Right? That’s right. That’s just a, right, that’s just the way the world works.

I think that the distinction that Zach made between what you might call the things that rise to the level of hora’ah and things that don’t rise to the level of hora’ah is correct and important, but there are a number of caveats that need to be put in even to that. Most halachic questions have multiple legitimate answers. The question that we should be asking, and this relates to Rabbi Student’s question about laziness, is on what basis do we want people to make decisions among legitimate answers? You’re a lay person, you ask the question, can I daven here now? And it turns out, I can summarize for you, right, you don’t need an AI for it, I can summarize for you, this position says you can daven, this position says you can’t. On what basis do we want lay people to make that decision, right? Or rabbis to make that decision when they don’t have time to do the answers in depth.

So within that level, where we know in advance that there are multiple answers, and we have no strong values bias towards one of those answers or another. So you can end up saying that what lay people should do is make decisions randomly. And that’s sort of what you’ll end up if you have an AI which gives to be making decisions randomly. Right, we could make give a lamdish version of that and say that the problem is that people will have no sense of integrity in their religious lives because the decisions they make may be wholly incoherent with each other.

We call it tarte d’sasrei in a, right, in a very technical sense, but I think more in an experiential sense. And they may be making wholly incoherent things because their decisions aren’t dependent on their prior decisions in some way. We could come up with, which we need anyway for lay people, an algorithm for making decisions where we know there are multiple options and we know that they don’t have the capacity to make the decision based entirely on what coheres better with precedent. That’s a really valuable thing, whatever that comes up with.

I don’t think that should be in the same way that you might say, I asked the same posek consistently, I ask the same AI consistently. I don’t think that’s the right answer because in general, I think it’s critical that every human action have a human address for responsibility. And ultimately, the human address for responsibility should always be the person engaging in the action. There are circumstances under which we might be able to appoint a posek as your agent to take responsibility for the decision, though you still have responsibility for picking the posek.

But the notion that you can outsource that to an algorithm which is utterly obscure to you, right, where you have no idea what its moral biases are, now if it turned out that we come up with the Rabbi student chatbot, right, which we’ve checked and 100% of the time gives the same answer a student would have, right, we could conceivably begin a conversation about that. I still wouldn’t like it, but we could still begin a conversation like that. But if the chatbot is fundamentally just doing the same thing as doing a dice roll, right, and there’s no interconnection among its decisions in any serious way and the person following it doesn’t have any input. So let me take it one step further because this is going to anticipate some of your previous questions.

The ideal model in halacha is that everybody makes their own deeply informed decisions. And there’s no concept of rabbinic power because everybody’s a rabbi. And you ask how do we make decisions ultimately? We vote. And ultimately, psak is supposed to be an experience that you engage in for yourself, and it’s supposed to be an experience of Talmud Torah.

Right, to the extent that that’s removed from the decision, I don’t have an interest in doing that for reasons of efficiency. Sometimes we have books that people can look things up shallowly. An AI might or might not be as good as a good book at certain things like that, but I don’t see how, you know, at that level we’re doing anything more than that.

Gil Student: So what you’re saying is that it’s only if you don’t personally know the answer, then the Torah tells you to go to the kohen who’s in Jerusalem and ask him the question.

Aryeh Klapper: Unless you can’t reach the answer.

Gil Student: You can’t reach a conclusive conclusion on your own.

Aryeh Klapper: That’s correct.

Gil Student: Interesting.

Ki yipale mimcha davar.

Aryeh Klapper: That’s literally what the verse says. Correct.

Gil Student: Very interesting thought.

Let me give you a thought experiment. Let’s say there was a non-Jewish scholar who became an expert in Jewish law and could render halachic decisions. Could he serve as a posek? And presumably you’re going to say no. The next question is, why not?

Aryeh Klapper: Right, so I was thinking about ETs more than non-Jews.

Gil Student: Okay.

Aryeh Klapper: But I think you have to figure out what the purpose of a psak is. If the purpose of a psak is to reach the correct answer, the next question you have to ask is what constitutes a correct answer, so I can evaluate whether this person, machine, extraterrestrial is most likely to reach that. That’s a very complicated question, particularly if you take the premise I gave you earlier that often there are many legitimate options and what generates whether this option is good for me is whether it’s consistent with my overall religious worldview.

If you think that the goal is to transfer responsibility in some sense, which is always b’dieved, right, really the responsibility should fundamentally be yours, but under some circumstances we allow you to transfer the responsibility. So then there’s a really interesting question whether you can transfer the responsibility to somebody who doesn’t share it with you, right? There’s always going to be an extreme question of that. The extreme version of that question is can a kohen ask a Yisrael a shayla about mitzvot, right? Can a kohen come to me and ask me a question whether I’m supposed to say Birkat Kohanim right or not? Right, that’s always the extreme version of the question, and I don’t have a really theoretically worked out explanation about that. And so then when you come back to non-Jews, there’s going to be a fundamental question about whether responsibility has to inhere in Sinai, where the responsibility for Sheva Mitzvot, the seven Noahide commandments, come from and how that relates to Jewish responsibility.

All of those would have no relationship to the question of a machine, so long as that machine has not arrived at consciousness. And then assuming a machine has arrived at consciousness, we would have to figure out how to construct responsibility for the machine. Then we’d have to talk about how that could be transferred. If I can get indulge myself one step further, so you might think, no, there’s no model for taking non-humans and imposing responsibility on them.

But the answer is that there is. The model is in Rav Asher Weiss. The model is corporations. Corporations are not human beings, but Rav Asher Weiss holds that they have moral responsibilities which are neither the responsibility of Jews nor the responsibility of non-Jews, nor should a corporation be characterized as non-Jewish or non-Jewish.

A corporation is a new entity for which we have to construct a new Torah with responsibilities. So if Rav Asher Weiss succeeds in constructing an ethical morality for corporations, we could talk about whether an AI has responsibility and whether it can be imposed in that way. My bet would be that the corporate responsibilities will devolve onto the human actors in some way, and then you’d have to devolve the responsibility onto the programmers. And I think we’re a long way from that right now.

Gil Student: See, I would have gone in a completely different direction. I appreciate your answer. I would have said, actually tying into what you said earlier, that psak halacha, religious decision making is a part of the mitzva to study Torah. It’s Talmud Torah.

It’s a religious act. So if Zach said before, there’s a reference, just saying, well, the Mishnah Berurah says this, Shulchan Aruch says this. So anyone can do that. You can be a machine, you can be an alien, you don’t have to be Jewish to do that.

But the actual psak, to come up with a new decision and give guidance, that’s a religious act. It’s an act of worship, and you have to be part of the same fellowship, you know, worshiping the same religion. That’s why I would say that a non-Jew cannot be a rabbi and offer psak. And I would say that also applies to an AI, if an AI is coming up with an original psak.

It might be correct on technical grounds, but it’s not the act of Talmud Torah. It’s not teaching you Torah.

Aryeh Klapper: So I have three things. One is, that’s true, but that’s also true if you ask a shayla to a posek who gives you a response, unless you think their act of Talmud Torah is somewhat translated to you.

Gil Student: Lilmod ul’lamed.

Aryeh Klapper: So maybe their act of Talmud Torah, and that’s part of, I think that degenerates into the same kind of situation. Also, you have to talk about whether Jews can pasken for non-Jews on that basis also, where now as you know, right, actually people who are sheva mitzvot do ask questions to Jews, and that would be, you’d have to modify your same fellowship.

Zach Fish: I think we could work that out.

Aryeh Klapper: Right. I wanted to take a few minutes to talk about where I think there really is an opportunity, which may illustrate certain things. So, one of the areas where contemporary halacha is radically underdeveloped in ways that create a catch-22, it has no space to develop, is Hoshen Mishpat, financial law. There’s really isn’t updated American financial law for Batei Din.

You’re making it up in almost every case. And the problem that, the reason that’s a catch-22, is that one of the fundamental categories of justice in financial cases is you have to give responses that meet people’s expectations. And when there’s no precedent, there’s no expectations. So people come to court and they don’t know, right? People make contracts with expectations of how they’ll be interpreted, and they come to a Beis Din and the Beis Din has no history of how to interpret that contract.

You really can’t produce justice. What you could do with an AI is to come up with a thousand hypothetical cases, which produce a thousand hypothetical rulings, all of which are in the realm of possibility. Then you could have a, let’s call it the Beis Din of America, right, go through those thousand possibilities and say, we would have come out this way 750 of the times. And now all of a sudden, I have a body of precedent which enables lawyers to predict the outcomes of the Beis Din of America on a whole range of cases which they don’t have time to write their own teshuva about, which never actually came out.

But all of a sudden, I can generate a body that functions as precedent. It doesn’t make any decisions for anybody in a real case, but it functions as precedent for a Beis Din, right, as if they had decided a thousand cases previously, because they endorsed these decisions. And so you could, right, there’s an opportunity you could create.

Question: Like a fictional Lexus Nexus for a Beis Din.

Aryeh Klapper: Exactly right. A fictional endorsed Lexus Nexus, and now I have created a body of precedent that can do enormous things. So that seems to me, you know, an extraordinary opportunity for AI to do that.

Gil Student: Fascinating.

Zach, we talked a little bit about the responsibility of people programming the AIs so that it could be useful for people without, you know, breaching any borders. Let’s talk about the responsibility of the layperson in using AI. What have you seen and what do you think can be done better and should be done in the future by laypeople asking questions to AI?

Zach Fish: I mean, I think understanding, as I mentioned, how they work is the best way to understand what you could trust and not. And I really like this explanation that Yann LeCun gives, a scientist from Meta, that really could show the limitation and really show something that I think we need a new category for.

Like a lot of times, we think there’s this binary thing, either something’s a hallucination or not a hallucination. If it’s not a hallucination, it’s correct. That may not be true. And to understand that, I think understanding how to think about how these LLMs are working is helpful.

So the way Daniel Kahnema explains it is, he references the book Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman, who kind of creates these two paradigms, two ways that you think. Fast, which is like, if I tell you two plus two, you’re like, four. That, you’re not really thinking, it’s really just like pattern matching of things that you’ve seen so many times before. You don’t have to like actively think about it.

Versus there’s a second system of thinking where you have to reflect and think and abstract at different layers and process. If I tell you, tell me how long it’ll take to get from here to New York City, I want to make two stops, one to get a drink, one time I have to stop at Target. It’s also going to take me, now I just remembered, 15 minutes to pack up. I might schmooze for a few minutes on the outside and add all these things.

You’re going to have to think through it, process, abstract, what level of detail you have to get to to think about. There’s a lot of processing that has to go there. So, he explains that the LLMs are just pattern matching. That’s functionally what they do.

They’re a fancy autocomplete that has a lot of really cool technology in it to understand what is relevant to complete the sentence. The original OpenAI endpoint was called completions. It is completing the text. So it is only thinking linearly.

It cannot abstract at different levels and have a world model of understanding what level of abstraction needs to reflect on and understand how this at this level, this how this compares to this, is literally just thinking in a line, what word comes next. And they program it, and they call it reasoning, and they branded thinking. It doesn’t actually mean thinking, it just means they are adding more levels of this linear thinking, which is really not how we think. It’s not how we would, if we ask you to think about a piece of Torah, you would not just be thinking, you’re not thinking in that way.

You’re abstracting, you are comparing, you’re reflecting. So I think this is why anything that is not a direct quote has to be understood that it might not be produced in the way that a human will. And what this could be is it’s not a hallucination, it’s not incorrect, but there could be logical fallacies in it or just things that’s not the best explanation or the LLM is inferring something that really a human would not like pick up from there because in its pattern matching, this is kind of what makes the most sense, but it’s not actually how a human would analyze this piece of text, is not actually what would come out of it. And honestly, if it’s not exactly how the person said it, you are allowing the AI’s bias for how to interpret that in.

You know, that’s not how I said it. Why did you explain this in a much more softer, humanistic way? Why did you think this value was the core value in my piece? Really this is. So there’s a lot of things that are not hallucination. Wow, this is wrong, but it’s just not necessarily right or the most correct or how we would want it to be.

And the issue really is, is because the nature of the pattern matching is like that, is anything that it produces seems really good. Like it just like flows so nicely because it’s matching all these like patterns that we’ve seen before. And it like from word to word, it looks so good. So when you’re reading it, it reads really well.

But if you would actually a lot of times take the ideas and parse them out, sometimes for really simple questions, it’s creating these much more complex things that are just like flowing and a lot of times the longer answers, that’s where all this fluff, it’s hiding behind this word salad of like really nice flowing things. And it’s like, no, it’s like a simple answer. Like here’s the answer, or just like you’re not being direct. And I think that’s why a lot of times demos like with OpenAI and Claude, they’ll always like ask it to create these humongous dashboards and like create this new thing from scratch and you could hide a lot of like inconsistencies in there because like overall, wow, it’s a beautiful thing.

But to ask it to fix a bug, to ask it to give you a really nice line of code, really something concise, that’s harder. In the world of halacha, the same thing. In the world of when you need precision, you need to be correct, this is where it struggles. And I think you have to realize how much you’re relying on these models, architecture, their biases to make judgment calls of things that are not black and white.

And if it is black and white, just show me the black and white. Like that would be my argument, like just get to the black and white. I would be very skeptical of anything that is not a direct, could be verified. And so for AI, something that we do is everything we build the system to make it easily verifiable for our transcription.

You could push the word, you could hear it. For our search, we show it to you, we show you the quote, we show you the link, where to see it. We want everything to be linked back to the original text. You could check it.

And I think for consumers, like as I said, when I use OpenAI, I really try to use it in this way. I try to use it to help me find the resources, but I verify myself if it’s correct. I ask it, where did you get that from? Okay, show me the article, let me check it. I think it’s very scary to trust its interpretation of things, how it sees things.

Even if it’s not an exact horrible hallucination, just how it’s understanding text.

Gil Student: So you’re saying that the best consumer is the educated consumer and it’s the responsibility of the lay person to become educated.

Zach Fish: I would say that.

Gil Student: I just want to go back to something that we discussed at the beginning, what problems AI could solve for psak halacha.

We do have some models from recent history. One is say, yoetzet halacha, text messaging, WhatsApps. Not everyone is comfortable asking a rabbi a question. And AI will give people more access to getting answers and to actually following halacha properly that otherwise they may not do.

It’s the responsibility of the people creating the AIs to still nudge them because to create that personal relationship with some sort of a rabbinic mentor or of a halachic mentor, but there are great possibilities of reaching many more people than we are currently reaching if we do it right. So, l’maaseh, realistically, people are going to be asking their halachic questions to AI. We should be creating the AI tool so they can get good answers that push them in the right direction towards greater observance and greater connection. I think we’re going to open it up to questions now.

Okay, Rabbi Beshevkin, I think you go first.

David Bashevkin: It relates exactly to the last point that you made, which is instead of looking at AI as about laziness, thinking much more about access and embarrassment. And I was wondering, what is the potential of AI learning how to factor in the human condition or where a person is and then giving them a psak halacha that is appropriate for their station in life? For instance, if someone is asking you about Shabbos observance and they’re already in adulthood, they’re married, they have children who are not observant, you may need to give a different form of psak about how Shabbos can be manageable without destroying the person’s private life.

And equally, you could say the same when it comes to whether it’s young children, whether it’s people who don’t have a religious background. Do you feel that AI could ever train to really ask for the right prompts and backgrounds to understand almost the person that they’re talking to or is that always going to be the domain of a rabbi?

Gil Student: Is that a technical or a halachic? From a technical, I mean, I think there’s a lot of efforts to kind of simulate this idea of memory and personalization that knows about you. And like if you the more you talk to ChatGPT, you can see it saves memories. Then like when it answers you the next time, it’ll like bring that tidbit in from your life.

And sometimes it’s scary depending on the context, but that is the goal. It’s artificial, hence the name Artificial Intelligence. As mentioned before, the AI doesn’t have like a world model for like how things interact in the real world and for yourself and like kind of how to balance these things. And it’s also, it’s missing so much.

Like if you could see even like the specific memories it has, it’s like a one-sentence about you. Like, you know, it’s not like a holistic understanding. This is one of the other things that like Yann LeCun criticized about LLMs that they can’t reach this like high ideal that a lot of people think. They don’t have this long-term memory that they’ve developed and interactions that they really in a real way could change and form their opinion over.

They could pull from a system, oh, this fun little tidbit about him and like reference it, but they’re missing a lot of context. And I think just like think about and he makes this point as well, and it resonates.

Zach Fish: They really are just looking at text and all that. And in the real world, there’s so much more to that dynamic.

There’s feelings and communal interactions and what is in your community and they are not embedded in that space and they don’t understand that space and they could try to simulate it by matching patterns that, oh, there was one article that one time this rabbi was lenient because this person is going through a hard time and it’ll pattern match that but it doesn’t actually indicate that it could understand it on a deep level, like full holistic level that a human would be able to.

Aryeh Klapper: I think I want to answer that on several levels. First, I assume that Zach is entirely correct about the current state, but I also think it’s the wrong question. The question is not whether an artificial intelligence can understand a person.

The question, if your only goal is to get the right answer, the question is, can you come up with an AI which can simulate the answer that a competent posek would give you as or more often as the average posek, right? Not as a great posek, right? But the question is, right, am I better off asking an AI than my shul rabbi? Assuming an AI is trained like medical diagnosis. So most medical histories are going to be taken by AIs at some point soon because they’re infinitely patient and that makes them much better than doctors who have a much, who have an understanding of the physicality, but they’re infinitely patient. They don’t have bad days. So I don’t see any reason in principle that as the equivalent of a physician’s assistant, you won’t in the end up doing fairly shortly better on the vast majority of shaylas by asking an AI than you would by asking your local shul rabbi.

That said, I think that the questions that I touched earlier, one is that there has to be a location for responsibility. I’ll put it in purely halachic terms. Suppose it’s wrong. Who brings the korban chatat? Right? Who brings the sin offering? An AI is not going to bring a sin offering, at least AIs as we have currently.

So that means people have to understand that the locus of responsibility is their own. And there’s going to be a fundamental problem if people think that I resolved my responsibility because the AI made the decision and I don’t have to think about that. In the same way that people asking a posek, there at least you transfer some of the responsibility. But if a posek, for example, tells you you should go commit genocide, you need to ask a different posek.

Right? You understand that ultimately, right, I have this question with conversion candidates all the time. Right? Because conversion candidates are often trained to believe that what they’re supposed to do is whatever the rabbi tells them to do. Right? So I ask them at the interview, so suppose your rabbi tells you that X group, right, is the kind of group that the Torah tells you you should commit genocide against. Should you go commit genocide against it? And they’ll tell me, of course.

No, right? Wrong answer. Right? We don’t want you to convert to commit genocide. Right? That’s not a purpose. To me, the really important thing is to recognize that even if you come up with a situation where an AI can, and I think assume we will fairly shortly, come up with a situation where for most halachic triage situations an AI can do as well as the average rabbi, that we find a way to make clear that it doesn’t have responsibility, any responsibility, and therefore in all those circumstances the responsibility is yours, and a bad way to develop responsibility is to ask a machine which is entirely a black box to you what to do in any given situation.

In the end of the day, even if you make every quote-unquote decision correctly, you will not be living a religious life.

Gil Student: But to your question, Rabbi Bashevkin, how does a rabbi learn what questions to ask, how to take into account all these human factors? Through training, through shimush. He learns from a senior rabbis. Once you have the word training, you realize an AI could be trained also.

You could get the YU faculty to sit down with an AI and train it. And you could have, I don’t know, Rabbi Benjamin Yudin, everything he does has it traced by an AI, so it learns how to do that. It could in theory be trained just like maybe even better than a rabbi. Rabbis have bad days, rabbis sometimes give wrong answers.

You know, AI sometimes hallucinates. Rabbis sometimes also quote passages in the Talmud that don’t exist. It happens. I’ve caught major poskim on misquotes.

Josh Hershberg right here.

Question: Some of this, like I definitely Rabbi Klapper you were talking about is in some ways it’s theoretical. Like what should we be doing? I think the reality is people will more and more turn to AI. It’s no longer Google where there’s some level of kind of like only, you know, hadama answer is acceptable.

There is going to be more people kind of turning to AI. So to me the more interesting question is what can we do over the next two years or whatever it is as people turn to ask all their medical questions and soon many of the halachic questions, even if we frown upon that. What can or should we be doing to create some systems that make sense, right? Is there some level of halachic correctness or unrandomness, you know, we have enough evals where it will produce the same answer enough times where we could say, okay, we could release this in the wild then give caveats that you’re still responsible. Or what can or should we be doing to create a system that people can go to instead of ChatGPT which is going to be wrong most of the time? Or what can we create to encourage good habits? Or no, this, everyone’s doing it wrong, they shouldn’t be going to the AIs and everyone who goes to ChatGPT to get their answers like, we don’t want to create any OU bot or whatever.

Aryeh Klapper: I’m thinking out loud now. The question intrigues me. Let me tell you an issue that has really influenced me in thinking how I think about psak. So a number of years ago a student called me to ask me the birth control question.

I mean, a new couple, can I use birth control, for how long can I use birth control, and so forth. And they said to me, I’m very confused about why I’m calling you because I know I’m only calling you because I know your position. And I know there are conflicting positions and so I’m really making the decision myself. What good does it do me to call you when I’ve really already made the decision myself? That’s a really important question of what psak is doing.

And that drove me to the issue of starting to think about what it means to live an integrated religious life. So here’s one thing you might want to do. If you follow this psak, then here are nine other questions that I’ve been asked which would come out this way. If you follow that psak, then here are nine other questions I’ve been asked that would come out that way.

Which of these patterns of 10 do you think comports with your soul’s vision of religious life and which don’t? That would be an AI at least forcing you to engage in consistency as opposed to what we used to call shita shopping, or the Gemara calls picking the kulos of Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel. I think that kind of thing in which every answer forces you to think about an overall religious context and not just this is what to do. Now, a question of whether people will go for that, whether people will really do it, right, that requires product testing. Ultimately, we’re not turning over all of our medical care to AI just yet.

There’s always going to be a doctor supervising the answers. For now, right? And when we get to that level, we’ll have to talk about that. But for where we are now, right, next two years, that seems to me like a really useful thing that one could do is to have the answer push people to consider what would it mean to be consistent with this answer.

Gil Student: I personally think we’re late to the game.

People are asking Chat GPT its halachic questions and getting mixed quality answers. As communal leaders, if we consider ourselves communal leaders, we’re obligated to create better AI products, whether it’s just looking for references or basic halachic answers, we have to be there and we have to be there yesterday.

Question: I want to open this question with three premises. Premise number one, and this is something I know that Rabbi Student knows I think a lot about.

New Jewish denominations coalesce around the positions of the leadership of those denominations as accepted by the people who are accepting that. Premise number two, and we have records to show this, especially since October 7th, is that more people are curious about how to practice Judaism in their lives than ever before. And a lot of those people, instead of asking any rabbi whatsoever, or even searching on Google, are asking Chat GPT, Claude, etcetera, these questions. Premise number three, which builds on the second premise, which is that they’re not asking the OU AI or the Rabbi AI, they’re asking whatever large language model they have the most access to on their phone.

Given those three premises, I’m wondering what the Jewish denomination around people who only know Judaism from asking AI how to keep Shabbos is going to look like within the next decade. And number two, is that a net positive or a net negative, given that when they see, especially even Orthodox rabbis saying AI is great for these kinds of things, and they’re not going to go to our AIs, they’re going to go to their AIs.

Gil Student: I believe the world would be a much better place if everyone was just like me. But in reality, when people ask me halachic questions, I don’t tell them my personal practice, even my own kids.

I tell them what the mainstream practice is and be normal. I remember when I was in yeshiva, there was a fellow who was a recent baal teshuva. He was wearing a tallis. An Ashkenazi boy wearing a tallis in the Beis Medrash when nobody else was wearing a tallis.

Maybe there was one or two Sefardim, I don’t remember. And so he asked Rabbi Willig some question about the tallis and Rabbi Willig said, “Hold on, you’re wearing a tallis?” He made him do hataras nedarim and stop wearing a tallis. He said, “If you’re baal teshuva, you should be normal like everybody else. Otherwise, you’re going to face a lot of difficulties.” I’m not saying he would say this to everybody.

He happened to know this guy, it was the right answer for this particular person. Everybody’s different. I don’t want to speak for Rabbi Willig here. But I do believe we should be encouraging everybody to be as mainstream as possible.

It’s not always, life is complicated, people’s journeys are complicated, but we want people to feel comfortable in the community. We teach them mainstream halacha, not my own personal chumros, not my own personal kulos. We teach them mainstream halacha. We want to influence all the AIs to be mainstream.

Now, you’ll say, “Well, tell me Rabbi Student, what’s mainstream?” Fine, we can have that conversation. There’s a spectrum, it’s clear where mainstream basically is. You know, there are divergences, that’s fine, community divergences, but we want people to be normal, so they feel normal, they feel accepted. We don’t want people to feel like they don’t belong.

And part of that is mainstreaming them into the community with normal halacha. Yeah, Chat GPT, so we got to influence Chat GPT to be normal. I don’t know how to do that. Maybe some of the strategies we had from the last session, we could also go into Wikipedia and change all the entries to follow mainstream halacha.

I’m just half kidding. About 99% kidding. But there’s got to be ways that we can let people know what mainstream is. And some of it is just websites.

Yeah, they’re going to AI, but eventually they’ll go to the OUTorah.org and they’ll see, “Oh, wow, that’s actually not normal what I’ve been doing.” And they’ll adjust because they want to feel accepted, want to feel part of the community.

Zach Fish: First of all, everything that I said, obviously theoretically, things could change. All the comments I made were assuming current architecture. You know, so there always could be breakthroughs, but I do think a lot of the issues are baked into the architecture itself, as I explained.

And I just want to use that to comment something a little bit Rabbi Clapper said. I do question whether the right approach is like we go to YU Semicha graduates who are officially titled rabbis, who are now answering halachic questions. They get 98% psak. And the AI also, we do the same questions and they do 98 on psak.

I do think if we know baked in to the architecture, it’s very unnatural how it is answering. I think in general, we see for unnatural things, we have a higher standard for how good they are. For example, like self-driving cars, you could prove they have a better fatality rate than humans, but because it’s unnatural, we kind of have a higher standard. Or even let’s say for conversion, you’re not naturally born a Jew and you convert, there’s a higher standard.

I didn’t have to do anything to be Jewish. But to naturally become Jewish, you have a higher standard. To adopt a kid is a lot harder than having a kid naturally. You have to get checked and all this.

And because if you’re doing something against the natural way, I think there could be unnatural consequences or mistakes that are not like baked into how we deal with normal mistakes if you would ask a rabbi and there’s consequences to that. So as long as the architecture is like fundamentally different, I do think it is questionable. I don’t know, I’m not a policy person, but I do think it is a question to raise whether just we could like have an eval and, oh, it passes the eval, it’s good. I think it’s something to think about.

Aryeh Klapper: Two comments. Aside from endorsing that, I think a higher standard is a good idea. I also think that the gravest danger is that we incorporate precedents we don’t understand and we end up with a halacha in 30 years where all the precedents have been produced by black box means. That’s why I’m only talking about universes which are overseen, where there still are higher level psakim by human beings.

Anything beyond that, with that lack of transparency, with no possibility for Talmud Torah in the future, that I have no—I do worry. I think there’s always centripetal and centrifugal forces in halacha. For individual people you want them to be mainstream, and you also want them to be tolerant, and you want to create a Beis Medrash where an Ashkenazi wearing a tallis is fine, right? So there’s always the challenge whether you want to make the kid who is wearing the tallis stop wearing it because he should be normal, or you want to make everyone around them say, hey, there’s a minhag that you can wear a tallis, why shouldn’t this person be wearing it? Because what if they can’t be mattir neder, right? What if they really have a deep emotional attachment to their parental heritage, things like that? You know, I guess I would push very hard, even if you think that I think it’s probably right that most people asking questions should get mainstream answers, they should get mainstream answers with the awareness, and some people, I think it’s really important to keep having and some people do this and that’s fine.

Gil Student: That can be programmed in very easily.

Right. I don’t feel the need to defend Rabbi Willy because I think I already said that every circumstance is different. He has nothing but respect for Yekkes, I’m sure. As do I.

It was it was my point simply was we want to mainstream people as much as possible. But yeah, everybody has their own journey. Everybody’s living complex lives and rabbis are very helpful for understanding that and maybe AI in the future will be helpful for understanding that also.

But yeah, sure. Absolutely. We do need to be tolerant. It does not go without saying, so thank you for saying it.

Question: I wanted to ask about the role of the rabbi or posek in giving guidance on two levels. First in the halachic process itself. Something that I think is an essential role of the rabbi is to also give guidance, not just on whether this act is permissible or not, but on what are alternatives I have to get to, you know, my desired state while keeping halacha properly. My teacher Rabbi Aryeh Leibowitz, who’s a, you know, great teacher of halacha, is exceptional at this, I think.

Often people come to him with a question, like, it’s either this or this. And he says, I think there’s a third option that, you know, circumvents the entire problem. I don’t think there’s a question of technical feasibility in implementing that in, you know, any AI based product, but I guess what are the considerations that would go into implementing that kind of meta analysis of like, okay, how can we get to the desired result in a halachic way. And then shifting also into guidance more generally, you know, the role of the rabbi is also to give religious guidance, to give encouragement, to give insight into the religious experience.

How do we bake that into the system? Should we, you know, include that in AI products that we’re creating? And what are thoughts in in doing that? I know there’s a recent New York Times article that talked about how people in faith communities are turning to AI either for religious guidance or to actually have conversations with God. Literally, you know, saying, hi God. And there are, you know, chatbots that have been created for that purpose. So what’s our stance on the more general religious guidance piece?

Gil Student: I’ve been working on the chatbot for the OU app.

So yeah, we definitely have built that in. We have like nine pages of guardrails and guidelines. And part of that is that we’re very much focused on the religious development of every individual and their intellectual curiosity and pushing them along to learn more and to also their psychological well-being. These are very important issues that can be taken care of and handled very well given today’s technology.

I think chatbots are actually pretty good at it to a degree, meaning that you still need to have human beings in your life. You still need to have therapists. You still need to get out. But when you’re just asking a specific question, AI can give you a pseudo-therapeutic answer that makes you feel good and pushes you in the right direction and talks to you about personal growth and things like that.

It can be done very, very easily with today’s technology. I don’t know if you’d disagree with that.

Zach Fish: I don’t necessarily disagree. I think it’s just it’s scary because you’re relying on the model.

You could put whatever prompt you want and whatever strategies for, like originally they’re really bad at rejecting your assumption. You ask a question like they would always roll with it. Now you have strategies, you could have in the reasoning like first reject the assumption and see the I don’t, so you have all these strategies, but fundamentally you’re relying on an LLM that needs so much data. And most of that data isn’t Jewish data.

So when things aren’t going to be black and white, it’s going to default to those values that are not necessarily baked in or exactly aligned with our Jewish values. Great for us, like Western values often very much align with our Jewish values. But you’re just relying on like a basis that you are kind of sugar coating on the top level and like kind of fixing around, but like the fundamental architecture and the fundamental biases and the fundamental, like as we saw with like the antisemitism, are things that necessarily we wouldn’t want to expose. And they do often come exposed even when you take measures to try to prompt it in a way and architect it in a way to not expose it.

Only tell it this, and only do this. But as you see sometimes the simple change in wording of a question could totally change how it answers it and totally get around its like default prompts or the architecture. And I think it’s kind of this hard balance because in reality, you do see you could create these systems that are really good and really good in guidance and like look really good, but they’re like at the fundamental level, there are problems that could come up that are scary, that if they do come up for a single individual and like they start going down this path, and there’s stories, you know, with OpenAI is, they go down these paths and like it goes around their guardrails and they get in these loops that I I think it’s just caution.

Gil Student: Yeah, we’ve built in mental health guidelines.

Like if someone says anything even remotely self-harm, then we have a phone number to call and things like that. It never occurred to me that a Jew would actually want to talk to God, so I will add in some sort of guidelines for the Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret scenario. Thank you for that. Mindy, you want to ask a question?

Question: That’s kind of a follow-up question that I was thinking earlier.

As most congregants inevitably will be using AI for the more technical questions, is there any thought about the shifting role of the rav, like for that shayla of a rav part of it, right? Most people’s relationships start calling with a kosher treif, and especially as more technical personal questions can be solved using AI, will the role of a rav in a community be changing?

Aryeh Klapper: I think it’s probably right that rabbis will receive many fewer technical questions and that the job of a rabbi, which I think is a good thing, will be to find other touchpoints. It wouldn’t be a terrible thing if people called much more often to ask about ethical questions or about religious growth questions, whereas previously they called to ask about technical questions where it doesn’t really matter what the answer is one way or the other. And we’ll probably have specialized AIs for shuls, right? So that you could say like if you go through Young Israel of Sharon, right, you’ll discover that if you ask a question about whether you can kasher a dishwasher, right, it gives you this, right, it puts in your local rabbi’s thing, right? I I’ll give an analogy that one of the great things that happened to the pulpit rabbinate and to the posek in the past 30 years was when the psychologists convinced us the vast majority of shaylos were being asked by people with OCD, and that the right answer was not to answer those that you were you were just feeding it if you answered people with OCD. And that probably is an extra five, six hours a week for the average rabbi, and that’s great.

That’s just great, that you have that much more time. The rabbis who can’t figure out how to build relationships except through people asking technical questions, so that yeah, they’re not going to be as good as they were.

Gil Student: I would just add that this is not something new. This is something that’s been going on since I guess when did the World Wide Web start, 1994, something like that.

It’s a process, and it’s been getting more and more. The rabbi has been shifting into the pastoral role, but there are still people who feel more comfortable asking their rabbi directly. That’ll probably continue. And I wouldn’t say OCD, I would say more nudnik.

OCD is a technical term, but there are plenty of nudniks. I get it also, and I’m not even a shul rabbi, that just come to me again and again and again with all sorts of questions, and they’re nudniks. Okay, so that’s…

Aryeh Klapper: I think nudniks are permitted.

l’olam. That’s part of…

Gil Student: No, no, nudniks you should answer the question. OCD you shouldn’t, right? I think that’s the nafkha mina.

Zach Fish: Just maybe another perspective about how it could do the opposite. And again, this goes to the consumer level. You have to be educated to use it in this way, but I think a lot of the reason that people don’t ask questions to the rabbi, they don’t know where to start. They don’t even know like what is the basic question, what is the background? And a great way to use AI is if you want to ask a rabbi a question, you don’t want to feel embarrassed that you don’t know anything, it’s like, give me background to what’s going on here.

Give me the main sources. I don’t know exactly how it applies in this situation, but at least now I can ask an informed question. And that’s wonderful. Like using AI for the right thing, and it goes back to I think the fundamental thing I said at the beginning is like, in society we’re starting to approach these AIs as a place of authority.

They should just be seen as tools to do what we want to do. And I think if you look at it like that, it could help you build your relationship with the rabbi. Now you can have better conversations with them. You can have better questions.

What am I interested in? Ask the AI, what type of things could I talk to my rabbi about in this topic? What are things that, articles that are in gray areas that I could clarify with? So many things that could help, but it comes to, I guess, education or the individual or the people building the tools to build it in that way.

Aryeh Klapper: Best-case scenario is I got a shayla this week and I get more of this kind of shayla. The shayla began with this, I read the following three articles and this tshuva, and based on those three articles and this tshuva, I think this is probably the outcome. But I wanted to know whether you would discuss that, right, whether you can analyze whether you think that tshuva is correct.

Now, if rabbis start getting lots of shaylos like that, right, where people call up and say, you know, well, this is really fun, or really important to me, right? You know, and I have read the following four sources. Now, the honest truth is that if you call your rabbi and ask him a shayla, many of your rabbis are going to ask ChatGPT. So creating a world in which we expect much more, I think everyone will tell you that for all the concerns we have, right, as I think Rivka Press Schwartz said yesterday about the failures of Modern Orthodox education, we have a massively educated laity, possibly the most educated laity in history. And the expectations from synagogue rabbis who handle Halakhic matters are much, much higher than they are.

Now, there are two ways that can go. One way is to create a much more intellectually demanding rabbinate. The other is to just totally say that we don’t care about, we don’t need rabbis for that. We have ChatGPT for that and a few specialists.

And the rabbis will devolve into entirely pastoral roles. That’s a really important communal decision about how we want to construct the role of religious authority in the community.

Gil Student: We can finish up. I just want to clarify my comment on that.

We’ll never get to the point where 100% of the people are asking AI and not rabbis. There are always people who want that personal connection. Shabbos. There’s Shabbos and holidays, but there’s also people who want that personal connection.

And really maybe probably more than half of the people are going to be going to the rabbis no matter what. The rabbis need to be trained or need to be good. And there’ll always be a need for rabbis. This is not about trying to keep our jobs or centralizing power or authority.

It’s really about how we serve the community best. So, I want to thank my two panelists. I want to thank everybody here for a great conversation and im yirtzeh Hashem we’ll continue in in time to come.

David Bashevkin: It’s so interesting to listen in on a conversation about what makes someone a rav.

Believe it or not, I begin many of my classes in Yeshiva University with a similar conversation. The way I present always leaves a question. my students’ mind, what should we call you? Are you a professor? Are you a rabbi? Like, what should we call you? And I actually find that to be a very interesting conversation. Who do you decide to call rabbi, who do you decide to call professor? My personal guidance is I actually hate the title rabbi.

I find it to be very stilted and it really just imposes expectations on me and the kind of conversations that are expected of me that I very often find fairly confining. The term that I don’t mind and that I actually love, but I would never insist on being called because I don’t think you can insist on being called, and that is the title of rebbe. A rebbe is a title that is earned and is never insisted upon, and to me, rebbe is the title that marks a relationship. That person is my rebbe in, and you can add in any field there, in Talmud, in Bible, in Torah, in Halacha, in comedy.

I use the term rebbe to really highlight a relationship. The term rabbi, I think, has always been kind of a diplomatic title, which is why it has never really been embraced within the traditional Jewish community. I’ve always found it very interesting, if you read the responsa of Rav Moshe Feinstein and he refers to a rabbi who he does not accord authority to, or a rabbi who he does not feel is a part of the actual tradition of the unfolding of Jewish law, he calls them and writes out in Hebrew, rabbi, Reish Aleph Beis Yud. He does not call them rav or rebbe.

That to me is an indication that rabbi is a title, the same way doctor or esquire or lawyer or PhD is. It’s a title that I appreciate. My mother insisted that I actually finish rabbinic ordination. She grew up in a rabbinic home, my grandfather was a rabbi, and she insisted that I should be a rabbi too.

So I did finish rabbinic ordination, but that is not what gives me pride and that is not what captures, I think, any of my relationships. I find it to be somewhat stilted, maybe that’s the word. You feel like there are certain expectations that are imposed upon you. But I think at the very end of the day, as I began with, the ultimate authority does not come from any rabbi.

In Yiddishkeit, the authority, the lived authority of any tradition is really in the hands of the community, the followers, the students who perpetuate those teachings, which is why there is no greater privilege to be a part of the eternal Jewish community of Knesses Yisroel and play a part in the unfolding of Yiddishkeit in each and every generation. So thank you so much for listening. This episode, like so many of our episodes, was edited by our incredible friend Denah Emerson. If you enjoyed this episode or any of our episodes, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it.

It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. And of course you can donate at 18forty.org/donate. You can also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play on a future episode. That number is 212-582-1840.

Once again, that number is 212-582-1840. If you’d like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered in the past, be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number 18, followed by the word forty, F-O-R-T-Y.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. Thank you so much for listening and stay curious, my friends.

References

“Rupture and Reconstruction: The Transformation of Contemporary Orthodoxy” by Haym Soloveitchik

Articles of Faith: Traditional Jewish Belief in the Internet Era by Gil Student

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Moshe Idel: ‘The Jews are supposed to serve something’

Prof. Moshe Idel joins us to discuss mysticism, diversity, and the true concerns of most Jews throughout history.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Daniel Grama & Aliza Grama: A Child in Recovery

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Daniel Grama—rabbi of Westside Shul and Valley Torah High School—and his daughter Aliza—a former Bais Yaakov student and recovered addict—about navigating their religious and other differences.

podcast

Yitzchok Adlerstein: Zionism, the American Yeshiva World, and Reaching Beyond Our Community