Moshe Koppel, Malka Simkovich, and Tikvah Wiener: Is AI the New Printing Press?

We speak with Moshe Koppel, Malka Simkovich, and Tikvah Wiener about what the AI revolution will mean for the Jewish community.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast—recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit—we speak with Moshe Koppel, Malka Simkovich, and Tikvah Wiener about what the AI revolution will mean for the Jewish community.

- How is AI going to change the dynamics, cadence, and rhythm of Jewish life?

- Should we panic about AI replacing the role of creative human work?

- What can Jewish and world history teach us about this moment?

Tune in to hear a conversation about what AI can teach us about our own needs, especially the need for Shabbos.

Interview begins at 14:26.

Dr. Moshe Koppel is a computer scientist, Talmud scholar, and political activist. Moshe is a professor of computer science at Bar-Ilan University, and a prolific author of academic articles and books on Jewish thought, computer science, economics, political science, and other disciplines. He is the founding director of Kohelet, a conservative-libertarian think tank in Israel, and he advises members of the Knesset on legislative matters.

Dr. Malka Simkovich is the director and editor-in-chief of the Jewish Publication Society and previously served as the Crown-Ryan Chair of Jewish Studies and Director of the Catholic-Jewish Studies program at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. She earned a doctoral degree in Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism from Brandeis University and a Master’s degree in Hebrew Bible from Harvard University.

Tikvah Wiener is Founder and Co-Director of The Idea Institute, which, since 2014, has trained close to 2000 educators in project-based learning and innovative pedagogies. From 2018-2023, she was also Head of School of The Idea School, a Jewish, project-based learning high school in Tenafly, NJ.

For more18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_forty

WhatsApp: join here

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Bashevkin: Hi friends, and welcome to the 18Forty podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re continuing our exploration of AI, artificial intelligence. Thank you so much to our partners and sponsors in this entire series, ASF, the American Securities Fund. We’re so grateful for all of their incredible work and leadership on this issue.

This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 1840.org, that’s 18forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.If I think carefully enough, I can remember quite a bit of firsts, like the first time I did X, Y, or Z, or saw a new technology in my lifetime. What were the big, big technologies that came out in my lifetime? So I think the first first that I remember was when we got an Apple computer, the original Apple. That’s the 128k, the Macintosh. I remember the room that it was in, I remember playing Brickles when it came out.

I remember the transition from tapes to CDs. I remember the first time my father got a car phone. He was a doctor, he needed a car phone. So I remember when car phones came out.

I remember the first time that I saw a laser printer. For some reason, that was a big deal to me. The first time I saw a laser printer was at the home of my friend Yoni Statman. And Yoni, who I grew up with, his father always kind of had the latest technology.

It was the first house that I saw the internet in. I remember I looked up sports scores. It was the first time I saw the internet, probably the early 90s, I’m guessing like 93, 94, something like that. And it was in that very home that I saw the first laser printer.

And I was utterly shocked. I had seen printers beforehand, but it looked very clearly that a computer, or what we then associated with a computer had printed it. It, you know, had like kind of lines in it, the type didn’t, it didn’t look like a book. And then the first time I saw a laser printer, like a proper, really good strong, I’m like, oh my gosh, you can just write your own book in the house.Fast forwarding, I remember the first time that I saw YouTube, that I owe to my dear friend Morty Jacobs.

I was in the dorm room in Ner Yisroel. I don’t think it was his dorm room, it was in another group of friends. And it was probably 2007, 2008, and he showed me YouTube. What did he show me on YouTube? I believe he showed me the video Lazy Sunday, which was the first of those SNL digital shorts, which was amazing with Chris Parnell and Andy Samberg.

I also remember, and this also credit to Morty Jacobs, was the first in my crowd to have social media because when we were in Ner Yisroel, he was in Johns Hopkins and he was the first to get Facebook. I did not understand it at all. Why would you want this? Why would you need this? But now it’s become a regular part of life.And here we are in this moment, and all of us are all experiencing for the first time AI, artificial intelligence. We all have, whether it’s ChatGPT or Grok or any of the other systems that are online, we’re using it.

It’s slowly but surely becoming a part of our daily lives, and surely all of us are wondering, where does this take us next? It is hard to remember a time before social media. It’s hard to remember a time before streaming music when you’d have to go to Tower Records, and there were movies like Empire Records that was literally an entire movie about a store that sells music. Such stores don’t really exist anymore all that much. You have stores that sell instruments, you do not really have stores that sell CDs or tapes.

Those used to be fairly common. I remember there used to be one in the Five Towns. There were two, one on Central Avenue and then one kind of off Central near Boy’s World, I think. I don’t even know if that store is still there.

That’s a throwback.But when we see technology for the first time and you’re already old enough to remember other technologies that come out, kind of the lens with which you approach it is wondering, is this going to shape my life in similar ways? What is the comparison to the way AI will shape the future of our lives and the lives of our children and future generations? How is that going to be different than social media, than the shift, let’s say, from tapes to CDs? That wasn’t so dramatic. Or maybe it’s the advent of the laser printer, also not so dramatic. Yet all of us have this kind of haunting feeling in our hearts that a lot more is about to change than simply a shift from tapes to CDs, and particularly within our Jewish lives. lives.

There is a perspective that this change really disrupts, what does it mean now to write creative Torah? What is the definition so to speak of the Torah that we share and how is the advent of AI going to kind of reformulate and reshape the interiority and the very structure of our daily Jewish lives? There is a fantastic book, it’s in Hebrew. It’s an older book, it’s not super hard to find, but I find it to be absolutely fantastic. It is called Mechkarim b’sifrut ha’tshuvot. That is explorations and analysis in responsa literature.

Responsa literature is the literature throughout Jewish history. I find it to be the most fascinating area of Jewish thought and law. It is not the writings that they wrote in commentaries, you know, on the Talmud or on the Torah. Instead, these are correspondence that were sent to rabbis asking them to weigh in on the latest issues.

And this book, which was written by Rabbi Professor Yitzchak Zev Kahana, again, it’s called Mechkarim b’sifrut ha’tshuvot, it was put out in 1973. It’s a great book. It’s broken down on sections of how rabbinic responses, which the beauty of the responsa literature is not even just the rabbinic response, it’s really the questions. What were the questions that were bothering people? What were the developments in history that people were responding to that caused them to reach out to rabbinic literature? And in this book, there is an entire section on the reaction to the printing press.

Movable type. The movable type printing press which really revolutionized the way information was able to be codified and shared, began in the middle of the 15th century. Over here, he gives the date of 1438. I see other people give the date of 1450.

But it was in the 15th century, in the middle of the 15th century. It is normally attributed to Gutenberg, even though I believe in the Gutenberg Bible, his name appears nowhere, and for many years, it was not abundantly clear who we should attribute the innovation of the printing press to. But there is no question that the printing press was a massive shift in the way Jewish life was developed. We are known as the people of the book.

And surely as our own tradition which is shaped through our reaction and interpretation of the written word. And we have a very unique tradition that bifurcates between what we call the written Torah and the oral Torah. So what does it mean to have an oral Torah now that anything that we say can be written down for future generations to examine when the barrier for entry for print is lower to such a degree. And this became a major debate in Jewish law, in Halacha of how to treat the printing press.

He was a kabbalist and also an incredible writer known as the Ramami Pano, Rav Menachem Azarya mi’Pano was probably the first to weigh in on this, but the debate lasted literally for centuries. Jews debating what is the halachic status of print? Can we write a Sefer Torah using movable print? Can we write a divorce document, a halachic document? What does this mean for copyright law? This also began to emerge. If somebody writes and puts to print an entire set of the Rambam and then somebody else goes and uses that movable print to publish the same exact work of the Rambam, are they infringing on that earlier person’s, I’m using air quotes, like copyright? Is the person, you know, who spent thousands of dollars putting this printed edition of the Rambam together, does he have any rights to the work that he did or is anybody allowed to go ahead and publish those works? This is actually what gave rise to a very common feature of Hebrew books known as the haskama. A haskama is an approbation, and approbations, most people think approbations is trying to testify whether or not the writer is a good scholar or whether he’s righteous or pious.

That was not the original use of approbations. Approbations really began as a reaction to these copyright questions where rabbis would write on the front of books and say, no one else is allowed to publish an edition of fill in the blank, the Talmud, the Rambam, the Shulchan Aruch, or whatever it is. There were really famous and big fights over the printing of Rambam. We could talk about that a different time.

But if you’re curious to learn more, there’s a phenomenal article that was published, I believe in the Torah u’Madda journal by really one of the worldwide legal experts in copyright law. I’m pretty sure he wrote the legal textbook on copyright law. His name is David Nimmer. I think it’s called like Nimmer’s textbook or something.

It’s a cool name for a textbook after your last name. And he also wrote a fantastic article on the development of copyright law in the Jewish world that is worth looking at. And when they were having this fight over the centuries and literal centuries… centuries.

In the 19th century, there was a rabbi who I am very fond of. His writings, there’s a real confrontation with modernity in his works, with scholarship, and that is Reb Tzvi Hirsch Chayes, who’s sometimes known as the Maharatz Chayes, as an abbreviation. He’s famous in the yeshiva world because Reb Hutner’s daughter famously did her doctoral work, Rebbetzin Bruriah David Hutner of blessed memory, wrote her doctoral dissertation on the Maharatz Chayes, on Reb Tzvi Hirsch Chayes, in Columbia, also in the 1970s. It’s a really cool dissertation, and I know many yeshiva guys passed around to one another.

It was circulating when I was in yeshiva, and I have no reason to think that it is not still circulating. But in this book that I mentioned, Mechkarim b’Safrut HaTeshuvot, it cites from the responsa of Reb Tzvi Hirsch Chayes in his 11th responsa, where he actually acknowledges the fact that technological innovation is deliberately disruptive. And every generation, he writes, has their own struggle with how to adapt the continuity of Yiddishkeit, the continuity of Jewish law, and figure out how it should react and be integrated into new technological advancements and developments. There are times where you have bursts of innovation, and he says, v’ein l’cha davar she’ein lo zman u’makom.

Nothing doesn’t have its time and place, and everything is given its time to disrupt the world, and then the Jewish people need to figure out, so where does that leave Yiddishkeit? Do we retreat, do we go forward, do we integrate, do we bifurcate? And the Jewish people have had many different responses to these crises over history. In many ways, I look at the Jewish people as the laboratory for how to deal with the vicissitudes and the ever-changing dynamics of the world while at the same time preserving a continuity that stretches throughout generations that binds and connects the entirety of Knesses Yisrael, the collective body of the Jewish people. And that is why at our AI conference, I was so excited for our final session. We spoke about AI and the printing press.

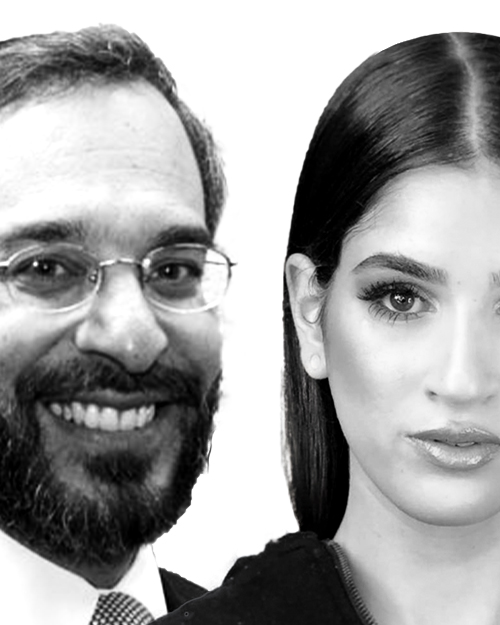

Is this an end or is this a beginning? How should we be looking at the way AI, artificial intelligence, is going to change the dynamics, the rhythm, and the cadence of Jewish life? We invited three incredible scholars to weigh in on this. I am so excited to introduce our three extraordinarily esteemed panelists, two of which are returning guests on 1840. And those two returning guests have actually both been on more than once. Our first guest, I am so excited to introduce, Professor Moshe Kopel, an esteemed computer scientist.

I love him from his original book Meta-Halacha, Logic, Intuition, and the Unfolding of Jewish Law, which draws quite a bit on the thought of Rav Tzadok HaKohen miLublin. It is worth reading. And of course, his more recent book from 2020, Judaism Straight Up. And let me just mention now because I think it’s Moshe Kopel’s finest work, he wrote an article many years ago in Tradition called Yiddishkeit Without Ideology.

I would urge in this moment to find that article, and I hope that we can put up a link to that article from Tradition in our show notes. Our second panelist, an esteemed professor, scholar of Jewish history, and we are drawing upon her wisdom. I am so excited to welcome back Malka Simkovich, who also sat on this panel, a dear friend of 1840, and I was so glad she was able to participate and share her wisdom. And finally, for the first time, Tikvah Wiener of Kadima Coaching.

She’s an educational consultant, extraordinarily wise, and does incredibly innovative work in the educational space. It is my absolute privilege and pleasure to introduce our panel with Moshe Kopel, Malka Simkovich, and Tikvah Wiener. You really want to hang on tight for this interview. There is a lot of disagreement and agreement in really the foundation of what this most recent modern evolution is going to do for meaning, for purpose, for Yiddishkeit, for our lives.

And it is with that in mind that I am so privileged to introduce our conversation from the 1840 in partnership with the American Securities Fund AI Summit. Okay, friends, this is really such a joy, and it has been really a delight to really gather with friends and talk out loud among ourselves about things that I genuinely believe are what the Talmud describes, dvarim ha’omdim b’rumo shel olam, matters that are really celestial and divine. The reason why I say that is because what this is really about is our own humanity, our own lives. And that is why this final session, which is about is AI the new printing press, what are the preparations.

we should be making to confront this new world? My mind immediately goes to the way social media affected the way humans interact, the way that we talk to one another, and the way that we speak to one another. But I wanted to begin on a very basic level to hear a little bit about how you have already, if you have, begun changing your work, things around your life with the advent of AI. And I wanted to start with Malka.

Malka Simkovich: Just a reminder that we don’t get the questions in advance, so thank you, David, I appreciate that.

And this has been a phenomenal conference, so I really appreciate that as well. When people ask me about AI, I think about it from the perspective of an author and a researcher and also from the perspective of an editor. And all of the things I’m going to share over the next hour or so are anecdotal. I don’t have data.

I’m not AI, and I’m not a professional at a serious foundation. I just speak from anecdotal experience. And my experience suggests that there’s huge panic in academia right now, and also stagnancy as a psychological response to what’s happening with AI. I was sharing in our group yesterday that I have a colleague in academia who put into ChatGPT a request.

He said to ChatGPT, use my own scholarship, and he put in his name, to write a new article on a topic that I am an expert on in the voice of Malcolm Gladwell. And what ChatGPT put out was so outstanding and so intriguing and well-written with such a good introductory hook that my friend said, I am never writing again. And he has not written anything since. This was about nine months ago.

He said, I’m done. I’ll teach and I’ll engage with my community, but I will not write anymore. It is simply not worth my time. The algorithm has exceeded my own creative capacity.

And that is one extreme, but I don’t think he’s alone. And on the other hand, you have maybe the older generation academics who are refusing to use AI, and as many of us over the past two days have said, and I agree, that’s maybe myopic and unrealistic to say I can get through the next however many decades of my career and just ignore the thing. I don’t think that that’s wise or practical or beneficial to those academics, but you have those on the other extreme as well. The big question is going to be what happens to those of us in the middle who want to use AI as a tool, but also want to think that we have capacity for our own creative ideas and that we have something unique to contribute.

I ask myself this question very often, but I’ve tricked myself into thinking that I do have something unique to contribute. And if you think that sincerely, as an academic, you have to work outside of AI before you go to it as a tool.

David Bashevkin: Tikvah?

Tikvah Wiener: So thank you. This has been amazing, David.

So thank you. So for the past 10 years, I’ve been focused on something called student-centered learning, which is trying to change education so that students have greater agency in the classroom. And it involves a lot of different components. It’s not one thing, it’s not one approach.

You have to do a whole bunch of shifts. You have to make a whole bunch of mindset shifts even within the teacher, and even within the students, and also within the parents who like sometimes are like, well, I did it this way, right? I walked uphill both ways in the snow, right? You’ve got to do it this way. What do you mean, right? You’re going to be working in groups. I literally got, I see in one of our group chats today, a parent is complaining there’s too much group work.

What do I say? So we have to think about whenever we change education, which seems to be a very slow field to change, especially Jewish education. We have to be aware of who else are we bringing along and how can we bring them along in ways that they can understand and are comfortable with. For me, in my work, which is to provide student-centered learning professional development to Jewish day schools, it’s a mouthful. We’re already seeing just how easy AI makes that work.

If you’re any kind of educator, general or Jewish educator, you can see how differentiating lessons can be made much easier using AI tools. But there’s so much that you could do. There are literal, if you go to Khanmigo, which is Khan Academy’s AI platform, or Magic School, there are so many tools you can use as an educator. So one thing that’s already become like de rigueur in our workshops is like, okay, so how are you using, you know, the AI tools for you? And then of course, the conversation shifts to how are the kids using AI tools.

So one podcaster, Angela Watson, she does Truth for Teachers. She’s like, I see this dystopia where all the kids are writing essays using AI and all the teachers are grading them using AI. So she’s just like, how do we prevent that from happening? So what are the guardrails that we need to put up so that that’s not happening? But how, I mean, to Malka’s very, you know, real point is like, how do we quell the panic among faculty, right, who are feeling threatened by this new technology? How do we help them adapt to this world where it actually is an amazing tool. Like, I can’t tell you how fast I can do some things that just took so long without it and make student-centered learning so much easier, giving the kids agency.

agency. So I would hate to go back to a time where like, I mean, I’m old enough to remember when everyone flooded the schools with iPads and there was zero plan. I promise you, if that was like I’m pulling the veil away from some schools, there was no plan, people, right? And a lot of times the iPad ended up in the drawer, right? Both for teacher and student. And now we know that the iPads were maybe a bad idea because there was no plan.

So how do we go into this new technology with a plan? Okay, there’s a teacher who really doesn’t want to use it. You know what? You’re the administrator. Have the whole plan for the school. Make a plan.

You ban cell phones, that’s freedom from. What’s freedom to? How is it a proactive plan and that you’re moving everyone along with you? And that’s what I would love to see happen really in the field.

David Bashevkin: Moshe, and I was wondering if you could speak to the first two responses. It’s something that I share as well, and I mentioned it last night, like the genuine panic, almost like the fear of watching a computer do what you have spent your entire life distinguishing yourself.

And for me, that is the development of ideas, the honing of ideas, and the sharing of ideas. And then all of a sudden you can put in a prompt, and it’s much faster and a lot of the writing can be excellent. It’s not always perfect, but it can be excellent. When you hear that angst, how do you relate as somebody involved within the Jewish community, within specifically AI? What is your position on the panic and the angst that people feel when they see the magnitude of what is coming?

Moshe Koppel: I think that angst is completely justified.

I think what’s coming in terms of people’s sense of self-worth, you know, those people, which is most people, who find meaning through the creative work that they do, I think this is going to be an absolute catastrophe. I think the number one problem that we’re facing, as we go, we’ve got plenty of time here. We’re going to talk about other catastrophes.

David Bashevkin: All of a sudden this chair feels like it’s 30 feet high.

So, and I’m wobbling about to fall. Keep going.

Moshe Koppel: I think that, you know, there are many potential dangers from AI, but I’m not a crazy doomer, but the one issue that I think is most frightening to me is the fact that most people will have absolutely nothing to do with themselves. And I’m not talking about people whose jobs, you know, are drudgery in the first place and they would be perfectly happy to be relieved of them.

I’m talking about people who are doing creative work and interesting work and find satisfaction in it. Young people will not be in those professions, okay? You know, whether it’s law, computer programming, medicine, education, you name it, all the white collar stuff. It’s not that the people who are currently there are going to get fired, it’s that the people who are up and coming and learning those things now are not going to get hired. And I’m not talking about the economic effects of this, which I think are minor, okay? I think that the real effects are psychological in terms of people’s sense of purpose and meaning in life.

This is going to be an absolute catastrophe.

David Bashevkin: I want to build on that and continue. I remember there was something that got a great deal of news attention as the popularity of the internet began to spread, and specifically within the Jewish community, there was something that has become known as the asifa. Asifa is a Hebrew word meaning gathering, and they rented out a baseball stadium and filled it, mostly from within the chasidic community, talking about the dangers of the internet.

Now, a lot of people like to chuckle, “Oh, the chasidim are putting their heads underground,” but there was some truth about the way that the internet was going to revolutionize and change society. If you were to imagine an asifa for the Jewish community in the coming of AI, what should be discussed? What do you think is the broad messaging? If you’ve filled a baseball stadium with Jews from all stripes and all backgrounds who are concerned about this question, what do you think the messaging should be specifically to the broader Jewish community about what we should be working on right now with the advent of AI around the corner?

Moshe Koppel: I was punting.

That was me punting very inelegantly. Yeah. All right. All right, I’ve had three seconds to think about that very fanciful question.

First of all, if most of the people in that asifa had two phones in their pockets, okay? L’maan yishmun v’l’maan yir’un as as they say, right? For those who didn’t get it, you have your dumb phone so that people will see it and your smartphone so that you can actually hear what you want to hear. Let me tell you about an interesting study, okay? I don’t remember who did this. I don’t think it was Jonathan Haidt, but it’s a kind of a Jonathan Haidt kind of study, okay? They asked people, how much would we have to pay you for you to go off social media for a month? You know, they said a lot of money, right? I don’t know, whatever, a few hundred dollars on average. Then they said, how much would we have to pay you for you and all your friends to go off social media for a month? They said, we’d pay you.

Okay. People are not happy. about being on social media. They don’t actually enjoy it, but they feel they have to do it because all their friends are doing it and if they don’t do it, they’ll just be out of it.

Social media has not served us well, okay? The question is what about AI? I think AI is different. I mean, I get tremendous benefit from AI, but sometimes, let me distinguish between two cases. You asked how we personally use AI. I didn’t answer that question.

I sometimes use AI essentially in the way that I was using Google until now, except it’s better, right? I’m looking for information instead of putting in a search term in Google, I kind of ask it in question form to Claude, and I get back a much better answer. And that’s really useful. Sometimes I do things that I would never have done otherwise because it’s too complicated, right? I want to know like which individual baseball statistics correlate best with runs scored when you look at the team statistics. If anybody wants to know the answer to this,

You into baseball?

David Bashevkin: I’m not, but I’m fascinated that you are.

Moshe Koppel: Oh, I’m totally, I’m a nut. If you take OPS, which is slugging plus on-base percentage, and you divide that by one minus on-base percentage, you multiply that by six and subtract two, that is the amount of runs a player is worth. Okay? If anybody’s a baseball fan here, mark that down.

This is the greatest, greatest statistic, greatest baseball statistic insight ever. Okay? AI does important stuff. But let me tell you how I usually use AI and how it’s actually, for the most part, does more harm than good for me. I wish I would stop doing it.

When I’m writing an essay or something like that, what I used to do is just sit down and write an essay. I was pretty good at it, okay? Now, I write kind of like something between an outline and the full text, like just kind of throw it down fast. And then I say, clean this up. Okay, and then I iterate, because it cleans it up and I’m not quite happy, and it doesn’t quite sound like me, and I iterate a bunch of times.

And by the time I’m finished iterating, A, it has taken me more time than if I would have just thought it through a little bit better and written it myself. And B, it doesn’t sound like me. Okay? That’s one of the main uses I have for it, and it’s bad. It actually is harmful.

It saves me nothing and it makes things worse.

David Bashevkin: You want to jump in, Tikvah?

Tikvah Wiener: Yeah. If I were to do the asifa, I think what I would say is this. I hear what Moshe’s saying, and when people say it’s really bad, it like makes my, you know, like gets me like that sick feeling in your stomach, right? Like, oh my God, what’s coming? Okay, I’m a big acolyte of Rabbi Sacks.

And Rabbi Sacks was not a person who spent time in despair. He talked about having hope, right? Which is, it’s also been meaningful because that is my name. Hope is an action verb, okay? And so I think we all live in a time, AI is one a thing, but obviously post October 7th, all the antisemitism, everything that’s going on in the world, I think we’re living in just very challenging times. I don’t think it’s helpful to live in that fear.

And when we make decisions out of fear, we tend to make bad decisions. So I think if I were gathering the Jewish people, I would remind them that we’ve been in places that have challenged our notion of what it means to be human before. You’ve named your podcast 1840, right? I think of the 19th century. There’s so much literature around.

Like, can you imagine being a Jew and Charles Darwin comes out with Origin of Species? You’re like, oh my God, what about Bereishit, right? And of course we have all the response now and we dealt with it. And now we’re like, right, we just, Rav Kook, we just expanded the palace of Torah around that, and who knows what a day is, and we made it work. And actually, we’re thriving. And I think about even this morning about the fact that like the virality of antisemitism on AI.

Well, antisemitism has always been called the virus and was it built in? Yes, it was, because even like the early biblical critics who threatened Judaism were doing it from anti-Jewish places because they felt Christ had to come and fix Judaism because it was bad. So we’ve been in places before where things have felt destabilizing. And I would say let’s learn the lesson also of not just the iPads but of social media. Now Haidt did this research for us, and we know how bad it was.

I don’t know if you heard Governor Cox a few days ago, and he called them the conflict entrepreneurs. They knew what they were unleashing on us. Let’s not be prey for them. I love this conference because you’re being proactive.

You’re saying let’s not be prey. And faith-based communities have such an important role to play here in saying we have this thing called the Torah where everything we do, we integrate it with it. So if we’re talking about human dignity, all the more so. Kal vachomer we’re talking about it with AI because it’s literally that.

So, I think if I were gathering them, I would remind us of that and not to live in the darkness.

David Bashevkin: I really appreciated that, Malka. I’m curious specifically from your vantage point as a historian who has watched the community respond to some really massive changes in the community. If you were given the microphone at this imagined gathering, the asifa, and we have the baseball stadium and all the Jews are there, where would you call their attention historically of what you see as a constructive response to dramatic Jewish change.?

Malka Simkovich: It’s a great question and before I answer that, like any good academic, I have to indirectly address the question. And I just think it’s interesting because the premise of a lot of our conversations over the past two days has been is AI good or is AI bad. Obviously, we’re not going to get to that answer and there’s a lot of variety in this room, but I wonder about the extent to which we’re just projecting our own natures and personalities and extent to which we’re a room of optimists and realists and pessimists, mostly the last. But when we’re thinking about AI and the future and is humankind going to inevitably improve, I think that we can’t get beyond our kind of natural disposition when it comes to the nature of humankind.

And that’s the case when we talk about AI. It’s also the case when we talk to AI, and we are asking or expecting an affable, agreeable, affirming entity that will essentially tell us that everything we say is correct, but here’s a better way to say it. I don’t know if we’re going to get to a point soon where AI will start arguing with us and being more combative and how that will change our relationship, but I just want to say that I think a lot of this is coming from our own dispositions and maybe there are fewer optimists in this room than I thought. Here’s the answer to your question.

A lot of people like to talk about writing as technology. In ancient times, people started to write and this threw the world into upheaval. I actually think that the second great technological development in this early history is more important, and that development is mail. It’s highways.

It’s what the Persians did at the end of the 6th century BCE and into the 5th century BCE when they built roads for the postal system, for the emperor. Because when the Persians built those highways and used it specifically to dispatch edicts and official statements of the emperor, suddenly people were held accountable to a higher voice than their very local homes, neighborhoods, and immediate communities. And now they had to think about a world beyond their immediate reality. Of course, this is way before there was any social media, but the mail was the social media.

And now they had to contend with very big questions about human freedom and accountability and whether they had a unique contribution to make, knowing that there was a higher authority that they had to answer to in a much more immediate way. Of course, there were always rulers and emperors that people were living under, but with the mail system, there was a closer connectivity and a sense of more immediate obligation to the host country under which they were living. And I think mail is a very interesting thing because it makes us think about the people beyond that we’ll never have immediate connection with, but maybe they’re producing something that threatens us. Or maybe they’re producing something that perfectly aligns with us and therefore we actually don’t have anything new to contribute.

Now, I think that there must have been some panic when mail started to show up, but I also think that the Jews living under Persian rule in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE used it as an incredible opportunity. I wouldn’t say to take control of their narrative, but certainly Jews responded right away with this technology to produce their own writings and to disseminate those writings. The end of the book of Esther is a great example of this, but it’s one of many examples of Jews writing and dispatching and transposing and sharing and translating. It’s not a mistake that the end of Esther provides a lot of detail about this dissemination and the reaches and the extent to which these letters made their way through this vast empire.

This is what Jews have done for centuries. They have faced these massive changes with resilience and with creativity. And I don’t want to be too optimistic, it would be against my nature. But I will just say that the willingness of the Jewish community under Persian rule to adopt this technology and then incorporate it into their own frameworks of thinking really ensured their survival and their unity.

David Bashevkin: I really love that example and that’s absolutely really, really, truly fascinating. One thing that I’ve been thinking about is the way that the human body reacts when it loses one of its senses. God forbid, somebody who does not have sight, so their sense of hearing is magnified. They’re able to focus perhaps much more clearly on the different noises and sounds that are taking place.

When you think of AI and we all spoke about how it’s really changed the act of writing and creative activities, what are the senses that you hope are going to be magnified? What is the training and the specific types of skills that we need to magnify in an era when certain types of thinking, certain types of writing are no longer going to be where we’re getting the exercise? I’d like to start with Tikvah.

Tikvah Wiener: When I mentioned before like the student centered learning, it’s a whole host of things that you do. If you’re standing in front of the room and suddenly Chat GPT can do that better, can provide the information better or whatnot, then you have a problem. But one of the things that we do a lot is teach the Socratic seminar, which actually popped up a few times here.

We ended up in different Socratic seminars because we’re Jews. We have to, right? We have to like talk and discuss, right? So during lunch or, you know, in our facilitation groups. When you give students agency and you teach them how to have conversations, I think that that is actually the antidote to social media and even AI, because what you’re doing is you’re saying, I need you to bring these texts because it has to be evidence-based, it has to be text-based, right? So you’re teaching them how to do the research. You have to show them, they have to come to a conversation with knowledge and skills, and then they have to discuss and take on someone else’s perspective.

And a Socratic seminar is not a debate. It’s not a zero-sum game. Malka is a pessimist, I’m an optimist. I don’t want to debate Malka about who’s better because that’s a zero-sum game.

I want to say, I need Malka’s perspective because you know yourself, you are going to get too high, like you need someone to like puncture the balloon sometimes. So all of us in this room have a perspective and I was thinking about that yesterday in terms of the like, what does it mean to be human? I think some of it is we need each other and that’s part of what’s ailing us about social media and it’s going to ail us too about AI if we don’t let it. And so having students collaborate, communicate, be creative with each other, I think is the perfect antidote to AI, which is saying, you know, just let me do it all for you. And you as a teacher can now say, no, actually, I need you to be in this room and present and bring all of you, right, to this conversation.

David Bashevkin: Moshe, I’m curious when you think about the specific skills from your vantage point. You know, I’m sure everyone’s asking you from a professional point of view, what are the AI proof industries? I am curious about that, but I’m much more curious from your vantage point about the specific human skills that we should be magnifying and developing further along the lines of what Tikvah just shared. When you think of the skills and the specific human-centric qualities that we possess, which are the ones that you think are in most need of development?

Moshe Koppel: Let me start by talking about the ones that I think are most threatened. I liked Malka, your nail example.

I’ll tell you why. Here’s a way to think about what happened then. We used to live in tribes essentially, okay? Not just in the Amazon, but people thousands of years ago lived in communities that consisted of a few hundred people and altruism was enough in order to keep those tribes functioning reasonably well. What happened when you had things like mail and roads, etc., the size of the so-called community that you were dealing with was much larger, okay? And there’s a magic number called the Dunbar number, right, which is somewhere around 175.

Once you’re in a group that has more than the Dunbar number of people in it, altruism no longer functions sufficiently to keep the society together. And you need essentially to develop social norms, in particular norms regarding commerce and so forth, that make it possible for people who don’t have any kind of kinship relationship with each other to be able to function as a society. So, in fact, everything that we call social norms, right, developed as a result of communities getting bigger because of things like, you know, transportation and communication that developed. What’s happening now is that, first of all, among other things, transportation and communication are becoming much more refined, right? So that essentially you can be talking now with billions of people and that’s what’s going.

And what we need to do is develop new social norms that are appropriate for billions of people. It’s a completely different thing. The communities that we have now are generally divided along other lines than we’re accustomed to. Once it was proximity, and then after that, it was a proximity but in a much larger scale, or commercial interest, etc. Now people are dividing up into virtual communities where, you know, you’re in the community of, you know, left-handed knitters and things like that.

We did not evolve as human beings, our minds did not evolve for this kind of a society. So we’re going to have to develop appropriate social norms in order for us to be able to function in this kind of society and I don’t think that it’s possible for those norms to develop very slowly. They evolve, and the speed with which these changes are happening is a completely different scale than the scale at which norms can evolve. So just the two things that I think, aside from what I already mentioned, that are going to go very bad for us and for which we need to work desperately to catch up on, are one, attenuated social skills, right? The fact of the matter is that

Tikvah Wiener: They’re getting worse.

Moshe Koppel: Social skills are getting worse, okay? If people are interacting with virtual whatevers, or if they’re just walking around with their faces in their phones all day, this makes their social skills worse, okay? Also, intellectual skills are going to get worse for reasons similar to what I described being in my process of, you know, like we get lazy, okay? Instead of thinking things through, we kind of outsource to AI to think instead of us. Now, what happens when you do that, it’s like what happened when you got Waze, okay? Probably you, like me, you know, if you were driving from here home, you would kind of look at the map and after like a minute looking at the map, you more or less knew how to get there. You might get stuck in traffic to be fair, but you knew how to get there, right? Now with Waze, I don’t know about you, but I could tell you that like, if I drive to the corner, I turn on Waze. is, I don’t know why I do that, but I can’t get anywhere without Waze.

My phone isn’t working for some reason and I’ve got to get from here to there, I’m going, how am I going to get there? People used to do it, three years ago, I don’t know, 10 years ago. So, the same thing of course is going to happen with our intellectual abilities because we’re farming them out. So, we are losing essential skills and at the same time we are fundamentally changing the way the people we interact with and the way we interact with them and so forth. And as I said, I think we are going to have to evolve norms that regulate the way we do these things so that they don’t end up catastrophically, and I don’t think that we are going to be able to do that in time.

David Bashevkin: That is absolutely fascinating and brought back some really pleasant and also frustrating memories of my father having a map open trying to find how to get to New Hampshire. And when I was dating, the shift was taking place as I was dating. I began dating in the MapQuest era, where you had to print out directions how to get from your house to the person you were dating’s house, to the location, then back to her house, and back to your house, and it was I came with a file cabinet on every date. Pass me folder number three.

One thing that I have been thinking about for the last year and a half, I’ll share this, it’s not really embarrassment, it’s really a point of pride, is that I have been involved in group therapy, group work. I’ve definitely been in therapy as a younger one-on-one, but for the last year and a half, I’ve been involved in group therapy. And the focus of group therapy is to have people sit around and really only focus and communicate the immediacy of their own experience. What are you feeling right now? It’s not about digging up childhood.

And it’s transformed the way that I teach and the way that I interact because I’m able to pay attention much closer. And what I have found that AI, if anything, has taught me how to articulate what I want, which is a really incredible skill. I think a lot of people go through life, they may have some vague idea of what makes them nervous or what makes them anxious or maybe even what makes them happy, but they have a very hard time articulating what exactly do you want? And I look at AI as an exercise in that, and in some ways, group therapy being an antidote of learning how to articulate the immediate what am I feeling right now? People don’t often know how to do that. And I’m curious and I want to really turn it over to Malka, specifically the pessimist, by your own admission.

Malka Simkovich: I mean that word’s in motion but.

David Bashevkin: Yeah. But you have spent a really impressive career in the academic world. Now you are the editor of a major historic Jewish publisher, JPS, and I’m curious for you, where is your mind going for your own self-development? Where are you thinking, where am I going to be useful next? And on a very personal level, what are the skills that you are trying to grasp and hold on to more now that so much of what you’ve spent your career doing has radically changed?

Malka Simkovich: Wow.

That’s a huge question and I’m not going to bore you with all my feelings about the second century BCE, but in a broader sense, I think that one thing that right now AI doesn’t do well is express doubt and humility. When you ask AI a question, it might invite you to refine the question and that could be a good skill for you cognitively to really think about what you’re trying to say, what you’re feeling and thinking, but what AI will ultimately give you, likely, is a highly confident answer that leaves you, maybe not you, but leaves one with a sense that they’ve reached kind of the objective threshold of truth. AI, in that sense, is very unhuman because when we’re in dialogue with another individual or we’re in conversation with the community, you can gauge, even if you’re speaking over Zoom, facial features, body language, intonations, hesitation, doubt, and also all those infinite gradations of humility in between. And then you have many more tools of discernment to assess critically whether you’re going to accept that information that you have received.

AI right now is not very insecure. Now, it could be that over time it will become more humanized and say, I think, but I’m not sure, that this is my answer, but also I advise you to go to Claude and Grok. So that’s not where it is right now. But I think going back to what Tikvah said, one advantage that we might have over AI is that when we’re engaging as one individual with this voiceless voice, that’s a one-to-one interaction, and really cannot mimic the distinctive, unique dynamics that are formed between all the individuals in this room as a unique community unless they start talking to each other.

And then I’m as worried as Moshe, I guess. But right now, the communities that we can build, I think, give us a leg up. And in those interactions, we see all the nuances of human experience.

David Bashevkin: Tikvah, I’d like to hear a little bit building on that specifically within the context of Jewish schools.

You do quite a bit of coaching with teachers and with administrators, talking about the direction of schools. What do you hope? I mean, I’ve seen curricula for teaching social emotional learning. I’ve seen all these tests and I honestly anytime I see a new curriculum, I look at it with a little bit of skepticism. Like it’s hard to have lesson one, you know, how to be polite and nice, past, you know, the kindergarten age.

And I’m curious, what do you think is the direction schools need to be going in, in a very specific way, now that it’s no longer the place where you have access to information? What are schools building? They’re not libraries anymore. You can have that on your home computer. What do you want to see developing further in Jewish schools to respond to the skills that we need most in the era of AI?

Tikvah Wiener: When we work, we don’t really work with curricula. We’ll take any curricula or any hashkafa that a school has, and we’ll say, okay, how can we help make your school more student-centered, right? So it doesn’t really matter what the content and skills are.

You can just tell us like, this is the content I want to teach in this grade, these are the skills I want to develop. What we’ll actually then encourage is, okay, so how are you also developing the skills of collaboration, communication, creativity, the social skills? How are you actually embedding social and emotional learning into the curricula? Okay, well if I’m having a conversation with someone, I need to learn I shouldn’t actually interrupt them, and to your point about group therapy, which is I need to learn how to listen to somebody else, right? Because that’s actually the thing that is ailing society as a whole, right? Is I just want to lob things over to you on social media, watch them explode and then walk away, right? So, these are the kinds of things that we’re working with schools and the way that we generally work is there’s like this one and done often philosophy of professional development. You know, someone exciting and fun is going to come and like jump on a table. I literally was in a workshop like that, and he’s amazing.

I don’t know if any of you have seen Ron Clark, he’s incredible, but that doesn’t teach me how to do all of this into my particular class into my particular classroom. And that’s certainly true for Judaic studies where you can have a plethora of resources in general studies. You want to look up Socratic seminar in 10th and 11th grade, you know, American history or English, whatever it is, there are millions of answers you’ll get. That’s not the case in Judaic studies, right? So how do we help everyone in a Jewish school move that forward? And really the how is really what we’re concerned with, right? How are you teaching so that kids are getting the skills that they need to succeed in this world? I think also if you look at, you know, what happened in Utah, what’s been happening with school shootings, you’re seeing the most vulnerable people in our population and that we’re not serving them, right? You see people who have gone very, very astray, and those are the canaries in the coal mine, right? Those are the extremes.

It makes me think like, what are we doing not just with social, I agree with you, like the social emotional curricula or like, is it an add on? Are you just like, okay, so once a week we’re gonna talk about our feelings. Is that really going to do the trick with everything that’s going on in the world? It’s like, no, to your point, a school should be a place where I really learn how to live in this new world. And so I need many more things than just, you know, how to, you know, read Shakespeare. But I want to give a shout out to the Tikvah Fund because I think also, and what Malka is saying is I do think we need knowledge.

I still think we need to teach the students, to your point, like to make it hard. Like, no, it’s worth it to invest in this difficult text because you’re going to get something out of it as a human. And we as Jews really value that. So I think that it has to be this kind of wholesale, you know, philosophy of like, what are we doing in our schools?

David Bashevkin: Moshe, when you listen and think, you know, your full time job while you educate, you are not a Jewish educator first and foremost.

Moshe Koppel: Not at all.

David Bashevkin: Or at all. You’ve educated me, so you’ve educated some people. But when you think about the Jewish schooling system particularly in the United States where there’s been so much talk about the cost of Jewish education and we all instinctively know if you grow up embodied within the Jewish community, that school serves not just a function of the information and not just social emotional learning, but they kind of build the culture of the community that springs up around it.

What advice would you give from your sitting point about the direction or maybe some of the blind spots that schools may have in the way they need to rethink the Jewish educational experience?

Moshe Koppel: Okay, this is like way out of my area of expertise at all, but I did go to Yeshiva in New York, so. Look, I sent my kids to the closest school that had heat in the winter. I don’t think you learn anything in school. I didn’t learn anything in school.

Whatever, whatever I ever learned, just ’cause I was interested and I learned it. One thing that I find crazy, but that’s because my kids went to school in Israel and they actually got a pretty decent education, is I keep hearing, probably all know this, that these schools like charge an arm and a leg and there’s like the which school should you go in your gap year in Israel director that has a whole staff under them and all this kind of crap.

What is this? I mean, I went to school, I mean I went to Chofetz Chaim. There’s 25 guys in the class. They got some teacher from public school to come in the afternoon and teach us whatever they taught us, okay? And there was one principal, completely clueless. And that was the school.

There was nobody else there. There was like the janitor was like the third highest ranking employee of the school. And now it just seems to be like insane administrator inflation. I don’t know, if you ask me, talking as a cranky old guy, just fire them all and just teach these kids some something for God’s sake.

David Bashevkin: Fascinating. Yeah, we’re truly fascinating. Not the, not the response I was expecting. …No, because I, I am curious about the specific skills, not how you would restructure the administrative body of a school, but what are the skills that you would focus on to learn and to develop, not about how to use AI, but in complementing your own human development? When you see emotionally healthy people, which our schools are trying to foster emotionally healthy societies.

Moshe Koppel: No, I don’t see that happening at all. I don’t see that schools are trying to do that at all. I see that they’re coddling kids and turning them into emotional invalids.

That’s all I see. What they should, what they should be doing is saying, okay, now we’re going to learn and actually sit there and learn something for like an hour, and then say, now it’s recess time, go out and do whatever the hell you do out there, okay? Instead of like constantly coddling them and telling them that they’re okay.

David Bashevkin: You would have made an extraordinary 11th grade Rebbe. I could only imagine what you would have been like.

Malka, I do want to ask you one question because I think a lot about your work specifically about how Jewish communities internally learned about one another. And one thing that I’ve been looking at, the possibility of AI, and really in the larger project of 18Forty, is facilitating not information but facilitating experience so people know the different possibilities of what Jewish life can, in fact, be. Can you share a little bit historically about how Jews and the fascination or even the motivation, if it was at all, wanting to learn not texts of the Torah, but learning about other Jews’ lives who they did not have access to?

Malka Simkovich: Once again, David does not provide questions in advance. So, no.

No, I’m just kidding. So yes, Jews have always been intrigued by the Jews who live beyond and reached out to those other communities using the latest technology. And sometimes it was technology itself that was a point of contention. And those communities that had more advanced, first of all, more resources in general, none of this is going to surprise anyone here.

But the more affluent communities, the communities that had more resources and also more religious leadership, tended to use technology to be more paternalistic and to use technology and and letter writing specifically, to reach out to other communities and try to argue for what might be a normative practice of Judaism. And this use of technology, of course, is not limited to Jews and Judaism. And one of the questions that I have for you, David, is to what extent is any of this, don’t worry, I’ll answer it rhetorically in a second.

David Bashevkin: I’ll be asking the questions around here.

Malka Simkovich: To what extent is any of this really specific to Judaism? When we talk about, is Judaism ready to face AI? A lot of the talk yesterday, especially, presumed a level of Jewish exceptionalism and singularity that I’m just not convinced. Yes, of course, the Jewish people have a particular set of scriptures and a particular set of values and shared experiences and history, and I’m not here to deny that. But at the same time, I’m also not convinced that other communities are experiencing these questions, especially communities of faith, that make them less equipped or better equipped to deal with this. And I’ll give one historical example, since you asked about history.

In the first century BCE, there were two major libraries. Most people only know about one and that’s the library of Alexandria. But in fact, there was a huge library in Pergamum. And the Pergamum library was trying to compete with the Alexandrian library.

And they were producing as many texts as they could. They used papyrus, they used paper, and they needed the papyrus of Egypt to produce their books. And so they were importing all this papyrus. They were buying paper from Alexandria, from Egypt, until Alexandrian authorities said, what are we doing? We’re selling paper to our competitors in Pergamum who are using it to put together these books and enhance their gorgeous library, which is a symbol of knowledge, which is a symbol of power, which is a symbol of authority.

We don’t want to do that. We want to have. have the best library and the best museum, so we’re no longer importing paper to Pergamum. And what happened in Pergamum is that they said, that’s fine, we’re going to start to process our own paper.

We’re going to find a workaround and we are going to find alternate sources of papyrus, and they did that. And today, the truth is my analogy doesn’t totally hold because we still all know Alexandria as being the better library. But Pergamum essentially went off and became siloed socially and intellectually and produced its own orbit of intellectual production. And they had their own museum with their own sources of paper.

Now, what’s the nimshal? I’m not sure exactly. I’m going to get there. The meaning of the story is that I think that sometimes we can weaponize these new technologies in a way that works against ourselves. And we have to be very careful to keep those higher ideals and values at the foreground as we think about these new developments which are taking place so quickly.

If our goal is to maintain a global community, to strengthen connection, to build stronger bonds with one another, then we have to be very careful. There was some talk earlier today about whether there should be a Jewish chat GBT. That might solve some interesting questions in the short term, but in the long term, what does that do to further silo the Jewish community or the particular Jewish organizations working on that particular chat or AI model? What does that do to those broader relationships? David, I forgot your question.

David Bashevkin: I very much appreciate that.

But to answer the question that you posed at me and before we turn over the questions, my answer for Jewish exceptionalism, particularly as it relates to AI, is a one word answer, and it is Shabbos. I genuinely believe to my absolute core that the Shabbos observant Jewish community, the fact that we have managed, it is 2025 and we have elderly, middle-aged, young children who have grown up with the experience of Shabbos, to know how novel that is for the world, that you read op-eds every six months in the New York Times and the Washington Post about people saying, wouldn’t it be amazing if we just unplugged for a little bit? And we have lived communities. It is not just the pious, it is not just the righteous, where we are actually fostering an ethic where we remove ourselves from technology. We still engage with it, we still work with it during the week, but we have a day where we really just focus on being and our own humanity.

To me, I really think is the prototype and the reason why I genuinely believe to my core that the Jewish community should not only be a part of this conversation but should be leading the conversation because we remember and we have every single week a reminder of life as it could have been otherwise. So that’s really 100% my answer. We do have time, of course, questions.

Question: Okay, this was an excellent panel.

Thank you so much. In terms of qualities, and Malka, you touched on this a bit, but I’m interested in it from a bit of a different angle. The quality of humility and of patience. I come from this really with a focus on human flourishing, human development, child development, soul formation.

When we are raising children in the AI era, thinking of what the day-to-day experience looks like for our kids, compared to the pre-digital age, right? So even just the visual aesthetic of growing up around a life of books, of shelves, of seeing shelves, of seeing libraries, of seeing a Beit Midrash. That evokes humility, of seeing people around you read and read lengthy books and getting through the book to the last page, of learning from wise teachers who’ve gone through sequence and mastery and shinun and failure and trial and failure and achievement. This is something that deeply concerns me and is the focus of a lot of the work that I do at Tikvah, is thinking about how to marry our current age to an educational vision which very often to me truthfully seems completely incompatible to raise children outside of a culture of books, outside of a culture of wise sages. You know, is this a question? I don’t know, but I’d love for you to elaborate more on kind of this culture of instant gratification.

The patience is disappearing for children. They can’t even wait long enough for Alexa to answer them, let alone look up something in an encyclopedia, which they don’t even know what that is. And then just more generally kind of humility as a deeply Jewish value and humility, I think, as something very deeply human. What is happening to that?

Malka Simkovich: I already spoke a little bit about this, so I’ll turn to my panelists, but I’ll just say in terms of gratification, I don’t think that there’s a binary between this generation or older generations who remember the time before and children.

When I was a kid and I did read a lot, I always started with the last page. Always, every single time. I know, it’s terrible. I remember reading the last page of 1984 and being like, well that was a waste.

But then I read the whole book. I mean, somehow I still did it. And even to this day, and this is it’s a bad habit, I always read the last page. So in terms of terms of that gratification and impatience, I assume that past generations have had their workarounds as well.

But I totally agree with you that the pleasure is in the process and that children are not going to learn that in the same way using technology. But I want to pass it on to my panelist.

Tikvah Wiener: Yeah. I mean to really build on what you’re saying, I think that word, the process is the learning.

And so how do we as educators take children through that process, especially, look, you can’t dictate what a child’s home life is like. Some parents are deciding to be screen-free, right? But some parents can be giving their kids a lot of screen time. We don’t know. What if school were a place where we were taking kids through a deliberate process? And you know, you can use digital tools.

I don’t think we should be afraid of them. You know, bring the AI in, bring other digital tools into the classroom, but show them that there’s a process. I mean, even taking the idea of failure, right? That is a skill that kids need to learn. And the test taking, right, is not the way that they learn it because then they learn this is the grade and that’s it.

But what does it mean to iterate on something and be slow, and you said deliberate. So yeah, I think that there’s like a huge possibility, opportunity even for us to, you know, rethink how we’re doing things and to make sure our rooms are filled with books, right? We know that kids will read. If they don’t even have to see you reading, right? There’s studies done on this, right? All they need to see is books around them and they will read.

Moshe Koppel: Yeah, I think kids should not get anywhere near screens until they’re at least like 14 years old or something like that.

My kids are now grown, they have their own kids and they hardly use smartphones even. And I achieved this, by the way, if you want to know the trick, by setting an extremely bad example, because I’m a techie. I’ve had my face in screens like all the time. And I think my kids at some point said, we don’t want to be that guy.

So I just lucked out that way. But but yes, I think it’s very important to all these skills that you’re talking about, if kids develop them until they’re whatever appropriate age in their early teens, then it’s probably less terrible for them to get on screens after that.

David Bashevkin: I just want to say something before we get to the next question. There’s two things.

A, I’ve always found it fascinating that the way that the Talmud articulates learning is literally through failure. With the Talmud in tractate Gittin says, Ein adam omed al divrei Torah ela im kein nichshal bahem, that you cannot stand up, you cannot have your footing on the ground visa vi Torah, unless you first have failed, unless you first suffered, unless you first were disappointed and you didn’t get it. It’s the only way to arrive at learning. I will say, and I’m going to mention this again, because I am raising young kids and to my own horror, you know, all of the systems that we have, my kids see plenty of screens every single day, every single morning, to the point where my three-year-old started calling me Daddy Pig after a little too much Peppa the Pig in the morning.

And that’s certainly as a Jewish parent was not a victory when my son started referring me to Daddy Pig. But I will say something. My wife and I put in a lot of effort in the way that we educate and introduce Shabbos, where we make Shabbos something that is so undeniably awesome. We brought back Shabbos parties.

I grew up with people having Shabbos parties. My kids wake up every Shabbos morning and there are cupcakes out for them, there’s cake out for them. Thank God, we live in a neighborhood where like their friends and the backyards are always open. I have so much confidence and I am such a long-term Shabbos optimist that I feel like a lot of parenting needs to shift into how do you introduce the notion of Shabbos to your kids? And it’s really interesting because when we first introduce it when they’re three, they freak out.

They don’t like Shabbos. They’re like, oh no, and we’re not afraid of that conversation. I’ve had conversations with every one of my children, why are you scared about Shabbos coming? And it’s always we’re not we don’t get to watch TV. So what do you get to do? What do we have differently? Am I ever on my computer? Am I ever at work? And we really put in a great deal of our parenting into transforming Shabbos not just into a fun and exciting time, but as an educational experience.

Tikvah Wiener: Can I piggy back on what you said just now? Because also at like, you know, we’ve been talking a lot about what ChatGPT can create better than maybe what we can create, right? And the whole notion of creativity has to be rethought. But it’s not because what you’re saying is Shabbos isn’t just about what you’re not doing. How do we create Shabbos? AI can’t do that for us because it’s not one thing. It’s coming down the stairs and smelling the cholent, right? You can’t recreate the.

Think about that, right? Ken Robinson talks about like anesthetic experiences, things that put us to sleep, and aesthetic, right? Where we’re woken up. And what you’re saying is how do we create a religion where we are waking up and creating, right, our experiences.

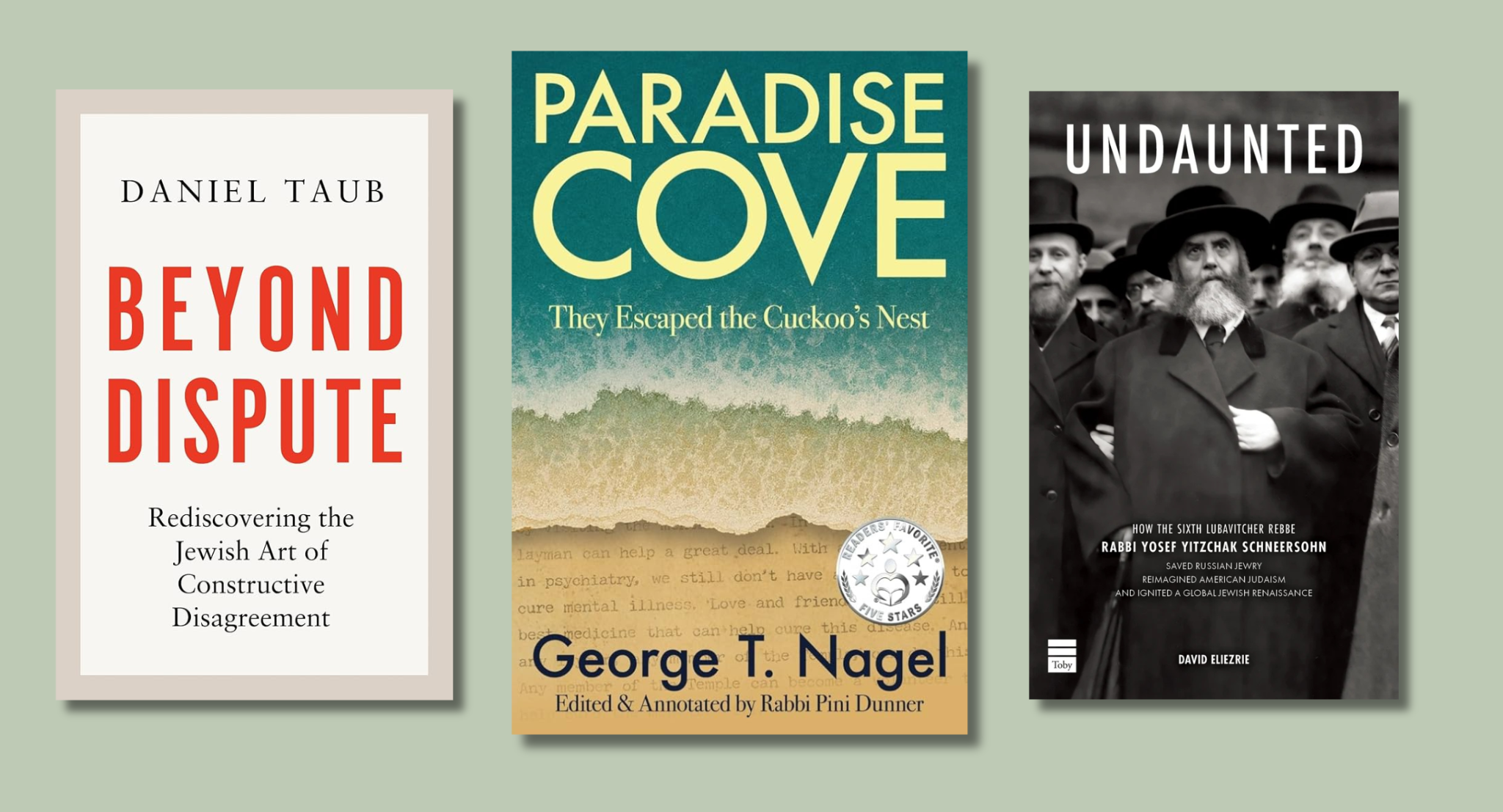

David Bashevkin: It’s why from the very beginning, it’s a strange part of 18Forty, but a part of what we do has always been around books related to Shabbos. We run an account called Shabbos Reads, which is just sharing what different people online read on Shabbos.

And I’ve been working with influencers. We just want you to share what you read on Shabbos. And thank God, we have Harvard Law professors, we’ve had a couple celebrities here and there. All we want you to do is share the cover of the book you read on Shabbos after.

And thank God, we have Harvard law professors, we’ve had a couple celebrities here and there. All we want you to do is share the cover of the book you read on Shabbos after. after Shabbos, but that’s a way of building culture. It’s not teaching young little kids, though people do share their children’s books.

We need to reintroduce Shabbos to ourselves. How do we make Shabbos something exciting that we’re looking forward to?

Question: Alright, so plugging right into this big Shabbos energy and noting that Moshe Capel did not answer the question about the asifa, straight forward. I want to connect to the asifa. I think about this a lot.

I’m so glad you asked this because I was one of the morons who chuckled, you know, when the Rabbonim were like, no, internet, this is bad. I think about this asifa, if not daily, then certainly weekly with great shame because it strikes me that they were more right than wrong. Now my question, and I understand full well the implications of, well we can’t just, you know, set new technologies aside and I understand full well there are uses. I ask this not necessarily by way of just provocation, but really as a kind of a philosophical exercise.

Is resistance possible? Can we go full Shabbos mode and say, look, as a community, this thing which we understand has good, it is more terrible than good, it will lead to some kind of destruction, we are out of this story.

Moshe Koppel I don’t think so, honestly. I think that Shabbos is just one example of a way in which Jews have already developed tools for dealing with the coming crisis before that crisis even existed. I want to give you two more examples.

So one of the things I’m worried about, as I said, is intellectual outsourcing, right? We depend on this thing. Conveniently, we actually have a tradition of arguing. That’s going to serve us well. The idea that learning for its own sake, right, is a value, and that we have a tradition of, right, machlokes between Beis Hillel, Beis Shammai, Rav and Shmuel, etc, etc, right? And thinking about the kinds of moral dilemmas that are right around the corner for us, I think serves us well.

I just want to mention as an aside, autonomous vehicles, which is going to be a big deal very soon, raise all kinds of moral dilemmas because you need to program in trolley problems, right? I mean, what do you do? You know, your car is going and the car needs to be programmed in advance to deal with a situation in which it can either, you know, kill one person this way or five people that way. And oddly enough, trolley problems, most people think they were invented by Philippa Foot in a paper in the British Journal of Philosophy in 1963 or Judith Jarvis Thompson after. They were invented by the Chazon Ish, okay? The Chazon Ish died in 1953 for those who don’t know. Look up in his Chiddushim on Sanhedrin, siman khaf hey, he absolutely invents trolley problems.

There’s no fat man being pushed off the bridge, but essentially everything important about the trolley problem are already in the Chazon Ish. That’s just one example. We have a tradition of dealing with moral dilemmas, arguing about them, thinking about them. I think we are in a very good position when it comes to the fear of completely outsourcing our moral and intellectual thought.

That’s number one. But another example, I was talking about we won’t have anything to do and we won’t find meaning in our jobs. This is a real problem. But it so happens that there is another old Jewish institution for batlanim, right? It’s called a kolel.

People dump on the kolel because there are all kinds of negative aspects to it. But the fact of the matter is, the kolel really does anticipate a society in which there’s so much leisure that people will not find meaning through their professions, but rather find meaning through learning lishma. That is a institution which will serve us very well, right? It won’t serve everybody very well. As you well know, Olam Haba is where tzaddikim go and learn uninterrupted 24/7, and it’s exactly the same thing for everybody else.

Gehenom is exactly the same thing for everybody else. The point is that if we adapt the kolel model, adapt the Shabbos model, adapt the learning model, we will head off a lot of the problems that we’re facing.

David Bashevkin: Do we have time for one more question?

Question: We’ve done a lot of talking about how the Jewish community is particularly situated in facing these questions and how we can be in positions ourselves and through our communities where we’re able to face it. I’m wondering if we can move the conversation explicitly outward.

My background is in really two parallel fields, kiruv and marketing, which is really the same field, and I’m happy to discuss why that is. But when I think about these questions, I think as someone who grew up outside of Jewish schools, outside of an Orthodox Jewish community and embraced it, what I consider later on, what most people consider very early on average, is how can we communicate this message to those outside of our community to maximize the positive that it can do in the face of AI for everyone else who does not have these advantages built in already?

David Bashevkin: I’ll just talk about the Shabbos piece. I genuinely believe that we have a very real responsibility to model what a Shabbos observant life can be, and particularly something that I’ve tried to do, and we did very early on in 18Forty, do a series on Shabbos, which is to model what I would call an accessible Shabbos possibility, which is actually not highlighting the strictest Shabbos observant communities, but highlighting communities where I have family members that observe Shabbos in a way that maybe your local Orthodox rabbi wouldn’t be thrilled, who wouldn’t hold it up as an example, but realizing the diversity of practice that we have in our. I always believe in starting inwards and slowly moving outwards, and I think that if the Jewish community preserves its own humanity and stands up as a model of humanity in our discourse, in the way that we discuss, the way that we argue, the way that we talk about ideas, I generally believe that we’re going to be in very great shape and we’re going to naturally be a model for the world, because the world is right now looking for models.

The whole world is scouring. Does anybody have this figured out? And I think it’s a very interesting moment to be a part of a community that to some degree has figured some of this out, some of what it means to be alive, some of the great mystery of existence. I wouldn’t call myself an optimist or a pessimist in this regard. I’m just confident.

I’m very confident in the tradition and the life and the way that we approach the question of existence. We have something very real. And I think modeling that for the world without in an evangelical or in a marketing way, I think people are beginning to take notice and are going to notice even more in a very organic way.

Tikvah Wiener: I think also we’ve talked a lot internally about our own Jewish experience, but we are citizens of a country, and we know that the educational system in this country is also broken, right? So how can we work together? How can we be good citizens and create, as you said, our own models and then share? I mean, we could be leading the charge in solving some of societal’s ills.

I think we should be, right? We have so much to contribute to American society. So I love your question because it really demands of us to say, what can I do to help fix this? Because in so many ways it’s not just AI, right? We know there’s so many problems. So I love that. I would love to see that sort of civic responsibility in what we’re doing.

Everyone will benefit.