Altie Karper: When a Book Is Banned

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Altie Karper, editorial director of Schocken Books, about censorship and cancel culture.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Altie Karper, editorial director of Schocken Books, about censorship and cancel culture.

Every community has boundaries, and every community needs a way to enforce those boundaries. As Altie’s experience publishing a book that received religious pushback tells us, it can be hard to gauge if something will be deemed appropriate. If a public figure says something that doesn’t fit within the boundaries of a community, there should be criticism, but this criticism can easily become sharp and unjust. We must ultimately remember that there are people behind the mistakes and they deserve to be given some benefit of the doubt.

- What amount of censorship is ok and what amount is too far?

- How should one criticize a public figure for saying something inappropriate?

- What kinds of criticism go too far?

- What is the difference between communal boundaries and cancel culture?

Tune in to hear a conversation on censorship, criticism, and cancellation.

References:

One People, Two Worlds by Ammiel Hirsch, Yaakov Yosef Reinman

Antisemitism: Here and Now by Deborah E. Lipstadt

To Heal a Fractured World by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

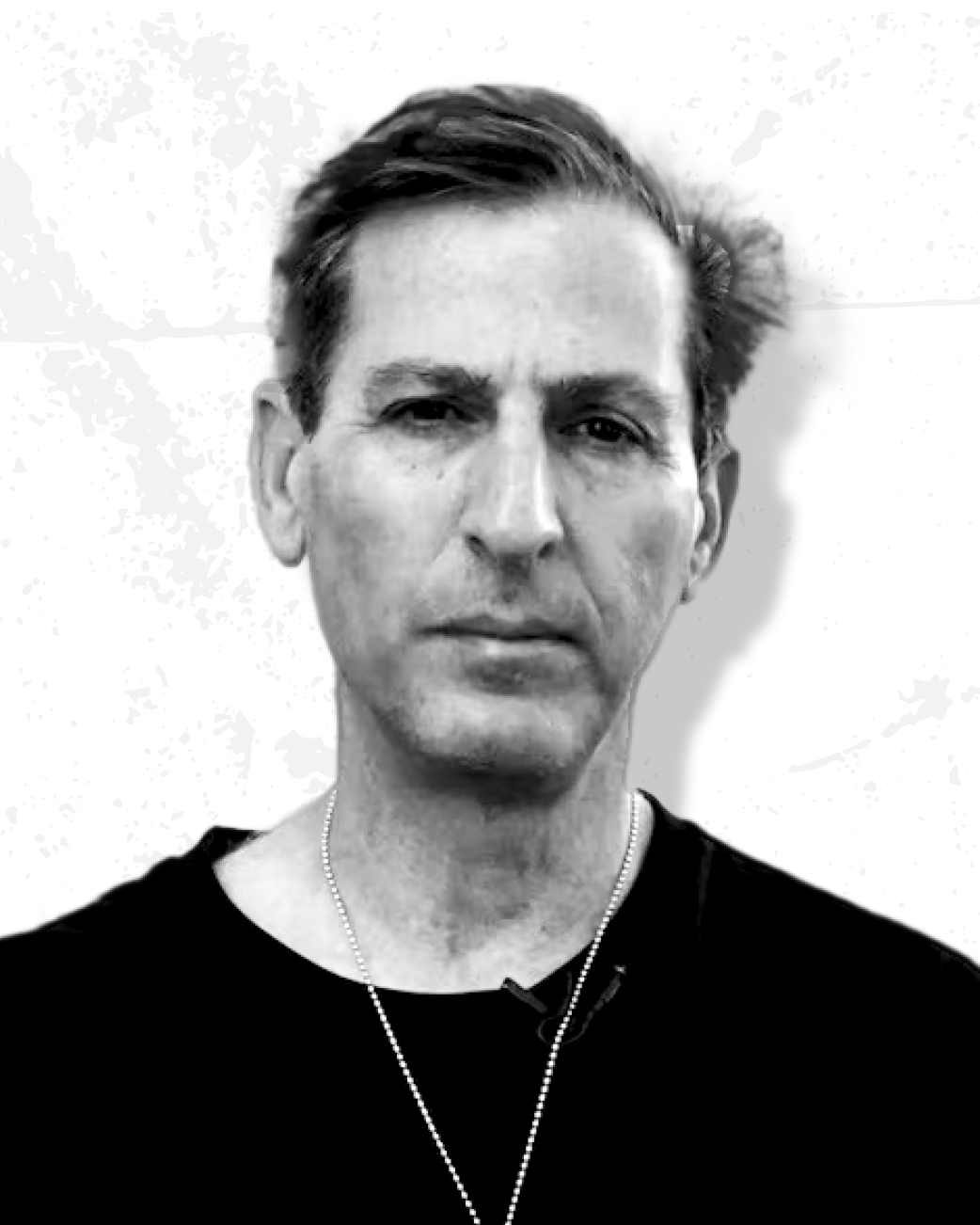

Altie Karper is the editorial director of Schocken Books, a division of Penguin Random House. Schocken has a long history as a major publisher of Jewish literature and an early publisher of great thinkers such as Kafka, Rosenzweig, Buber, and Agnon, among many others. As one of the leading names in Jewish publishing, Altie has worked on many of the great (and controversial) books of our time. No stranger to censorship battles, Altie brings to 18Forty her decades of thoughtful experience in the world of books, the Jewish community, and the boundaries around our ideas.

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless, Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring censorship and cancel culture. Yikes. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy, Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18Forty.org, where you can find videos, articles, recommended readings. All the good stuff.

I keep a letter right next to my bed in the drawer. I keep the letter right next to me nearly at all times for a very curious reason. It is not a letter addressed to me. It is actually addressed to my former boss, my boss at the time. It was sent to me about 10 years ago. And if you look at the envelope, it looks extraordinarily strange. It has stamped in red, it says, “Confidential, confidential,” stamped all over it. It was sent to my former boss. And inside the letter, it has a copy of something that I tweeted over 10 years ago. And I tweeted, “Here’s a movie I would recommend if I could have admitted watching this movie.” And it was a movie that definitely had inappropriate scenes. It was probably rated R, probably something I shouldn’t have watched in the first place, and certainly something that I should not have broadcast or advertised.

I did think that it was a fairly powerful film that had to do with relationships and how they deteriorate. It doesn’t matter which movie it was – though you can feel free to write in letters to find out and discover – but this person had written letters, not just to my former boss, but to a lot of very senior people at the OU with a print out of this tweet, and then they really did the work. They also printed out the IMDB page, or one of the pages where it says, what are all the inappropriate scenes in the movie. Which happens to be a great website for parents if you ever need to know, is this movie appropriate for my child? There are plenty of great websites where you can get that breakdown.

Sometimes the breakdowns are a little too graphic, to be perfectly honest with you, but it sure beats my mother’s strategy, which was going into Blockbuster and asking the 16 year old behind the counter, “Is this movie appropriate for my child?” That did not work as well. The advice that the 16 year olds gave my mother about the appropriateness of different films as a kid was not as value-driven as perhaps my mother would’ve wanted. But be it as it may, this letter did come to several senior people in the OU, and written in the letter was essentially saying that I, who at the time I believe was associate director of education for NCSY, should be fired. They were coming after me to fire me. And I think about this a lot, and I want to explain why I keep this next to my bed.

First and foremost, I never found out who sent this letter, and Lord knows I’ve tried. I’ve squinted. I kind of know which PO Box it came in. If any of our listeners sent this letter, feel free to come forward. It was really an extraordinary bold move. But it doesn’t matter who sent it, because honestly, they were right. I should not have shared that online. It was not an appropriate movie. It’s not something that somebody like myself in the position that I had should be sharing with others. And they were right. And it was a reminder to me that not everything that you’ve done or do needs to be broadcast to the entire world.

There is some element of self-censorship that is, I think, very healthy and normal and a part, not just of being a rabbi or educator, it’s a part of being an adult and a human being in the way that we share and transmit our values. So in one sense, I think that they were right. I did do something wrong. But in another sense, it highlights for me the scrutiny, that I think has only amplified, of the way and the purity of ideology that we insist upon. I think I know another rabbi who actually saw a very appropriate movie, but I believe – I’m probably butchering this, and I think he listens to this podcast every once in a while. He mentioned to his congregants that he took his children, or congregants saw him take his children, inside of a movie theater. And they gave him a lot of grief.

And I’m not here to litigate whether or not it’s appropriate, or whether you want your congregational rabbi sitting behind you in a movie theater, or recommending you movies that have scenes that are inappropriate. What I think this moment in time is really about, this angst that we see about cancel culture, which hopefully we’ll define a little bit more clearly, and censorship in general, is the question of the level of purity of ideology and practice that we insist upon, and the people who we look up to, and our role models, and the people who we associate with. And I think, in some very beautiful ways, we actually do associate and insist upon a very high level of ideological purity. We want the people who we look up to, we want the people who we get advice from, we want the affiliates of our community to have, as in any not just religious community, in any community, you want to have certain boundaries that reinforce the values that the community is meant to perpetuate.

But I also think that, as part of having boundaries, we need to have a smarter way of educating. Or, let me find a better word. Somebody one time used this term for me. Instead of “calling out,” they said “We are calling you in as a sign of friendship. As a sign of, we’re not trying to get you fired, we’re not trying to eliminate you from your job, but we’re trying to educate you in the position that you have and what you represent and the values that our community represents.” And that’s actually what my boss, he sat me down, he looked at the envelope, and he kind of smirked and smiled and said, “Yeah, this got sent to everybody where we work, which was absolutely mortifying.” He handed me the letter, which is why I now have it. And he looked at me, and he says, “David, you need to be a little bit more careful.”

I think that that was excellent advice, and what I’m still grappling with is, what is the right way to disagree? What is the right way to call somebody out if at all? I always think back, there was a documetary, I think it was on PBS, about Hasidic Life in America. The documentary is called A Life Apart: Hasidism in America, which is an absolutely charming film. I don’t know why it’s not as popular as it once was. I think they used to show it in a lot of classrooms. And there’s this one really beautiful scene in the fish market where there is a Chasidish fish guy. I think he’s a famous guy, Moishele the fish man. I don’t know what his name is. I think it was Moishele. And he was careful, he didn’t like videos and cameras. And the documentary filmmakers came into his store. And they started filming him, and he says, “No, I don’t want videos and television and movies. I don’t want this stuff.” Then he looked at them. He paused, and he looked at them. He says, “It’s for parnassa? It’s for your livelihood? It’s in order to make a living?” And they said, “Yes.” He says, “Oh, I don’t want to hurt anybody from making a living. I don’t want to stop anybody from making a living.”

So there are definitely, in anybody’s job, in anybody’s career, there are definitely clear boundaries of what you can and cannot do. I do think that that scene in the documentary crystallized for me the higher level of scrutiny that you need before going after somebody’s actual job. That we should take away their livelihood, that we should get them fired. And I think that in many ways, there are a lot of distinctions that can be made in the current moment that we’re in, talking about cancel culture. But I’m going to make two of them, and they’re from my own experiences. They’re from my own moments in my own life where people have come after me, and maybe there’s something flattering in there that there are people who think that I am of stature enough to even go after. I wish they went after my books to sell a couple more copies.

But there is a level of very honest and real scrutiny that you can have, or should have, when you are sharing with the public, and there’s a way that the public needs to react when they hear something that they don’t like, that they don’t approve of, that they don’t find appropriate and reflective of their values. Allow me to share two distinctions from the outset that I think are going to come up over and over again as it relates to cancel culture, as it relates to censorship at large.

The first distinction, and I think this is a really important one, and I heard this from a former guest of ours and a dear friend of mine, Rabbi Daniel Feldman, a Rosh yeshiva at Yeshiva University. He one time said, and maybe he heard this from Rabbi Sacks, I don’t honestly remember. He said you need to make a distinction between canceling and the culture. They are two very different things. Every community has mechanisms through which they can establish boundaries for the community. That’s not a religious phenomenon. I think political communities have that, and corporations and organizations and neighborhoods. Every community has boundaries of what they deem appropriate and inappropriate. That’s not necessarily something that we need to lament.

I think the part that gives me pause, at least, is the culture part. The concern that some very honest and real reasons so to speak cancel somebody, to say that we don’t want you having a platform or being a representative in our community, which I think there are plenty of reasons to have that feeling, but the concern is the culture that surrounds it. When we create a culture around this level of scrutiny of making sure that everybody has a sufficient level of ideological purity to be a part of the movement. And it reminds me of an analogy that I heard when I was in Yeshiva. It’s a pretty famous analogy. I think they say it in the name of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik. I’ve seen it quoted in other names. I believe it’s in the sefer, there’s a work, a commentary on Tomer Devorah, which is a work of Mussar and Jewish thought. And it has this commentary on the bottom by a rabbi who lives in Cleveland. It’s a blue copy, you find it all over the place.

And over there, the analogy that they use, which I find extraordinarily helpful and somewhat moving, it says, “The difference between healthy cancellation and cancel culture,” obviously this was written before the term cancel culture was popular, “the difference is the difference between the way your mother versus a house cat reacts when they see a mouse. If a mouse runs through the house,” and we actually had a mouse in our garage, and my wife at that moment, she thought of just moving to a different neighborhood. Like, we need to sell the house. There is a mouse in our garage. It’s time to just start a new life in a different community. She freaked out and screamed and made me go into the garage and bang and chase it away and promise that I did a good job. Because I’m known, a lot of times when my wife sends me after insects or anything that we find, and then I can’t find it, I lost it, I will sometimes, out of love, out of a great deal of love and affection, lie to her and say that I did in fact catch it. And if she then sees later on that same spider or whatever it was, which I also happen to be terrified of, I will lie. It must have been a different spider.

I don’t want her to not be able to go to sleep knowing that this lone spider is now dwelling in our midst because I lost it and couldn’t find it. But she freaks out, and she’ll scream, and she’ll just chase it out. It’s got to get out of this house. And a cat, if they see a mouse, does the same exact thing. They chase it, they’re excited, and they run after it until the mouse is gone. But what’s the difference? The difference between the way my wife reacts and the difference between the way a cat reacts is once the mouse is gone. What happens when that person or that antagonizer has now left? My wife is relieved. The cat, however, is quietly disappointed.

The cat, however, is thinking to itself, “I can’t wait until there’s another mouse to chase.” And that’s the concern that I have when I think very honest brokers who are looking to make sure that the values that we project to our community are sufficiently reflective of our community. I think that’s a good thing. What concerns me is the excitement of the chase. What concerns me is the thrill of the pursuit. When we’re after the person, and we are dogging and riling up others and trying to get our pitchforks together, that makes me nervous. And I think it’s in many ways reminiscent of a line I heard from Rabbi Shalom Carmy, who wrote in Tradition, he was actually quoting the former rabbi of my shul, the rabbi of my shul growing up, one of the greatest Jewish thinkers of all time, Rabbi Walter Wertzberger.

Rabbi Wertzberger noticed and had a turn of phrase on the commentary of the Ramban when discussing why the Egyptians were punished for subjugating the Jewish people in Egypt, even though there was a prediction. God prophesied that the Jewish people would be enslaved in Egypt. So what are we punishing the Egyptians for? This was pre-ordained. And there are a lot of answers to this question, but the answer of the Ramban was that, yes it was pre-ordained, yes because it was pre-ordained you shouldn’t necessarily blame the Egyptians for this. The problem is, there was undue amount of subjugation. They enslaved them more than what was necessary.

The turn of phrase that Rabbi Carmy says quoting Rabbi Wertzberger was, like Ramban, “He was concerned about the way even a justified war corrupts those who wage it.” Let me read that again because I think it’s so beautiful. “He was concerned,” talking about Rabbi Wertzberger based on this Ramban, “He was concerned about the way even a justified war corrupts those who wage it.” And I think sometimes the thrill of that pursuit, the thrill and excitement of chasing away those mice or those bad representatives, can actually corrupt the very people chasing them. If you do it with too much excitement, with too much undue thrill and personalizing the pursuit, and making it about that person, I think that has the ability, that the culture of cancel culture has the capacity, that even when justified, it’s a war that can corrupt those who wage it.

I think that’s a message both for the way we look at the use of cancel culture inside of our community and outside of our community. And I think the personalization leads me to a second anecdote and a second distinction. Those of you may know that when 18Forty was first started, we got into a little bit of hot water. I’m not going to recount the whole story now. I do it every four months. I’m not sure why. We know why, it’s to drum up ratings. Everybody likes a banned podcast. But it’s not really why.

It was very relevant here, and it was a really difficult period in my life and one that taught me a great deal, but I do know that there were people who were calling up my employers, and there was someone who called up a Rosh Yeshiva in Yeshiva University, saying this person needs to be removed. You’ve got to get this person out of an educational setting. They are not appropriate. Which was just everything that I’ve built for and worked for to inspire and educate Jewish people, it was soul-crushing.

I remember I called up a Rosh Yeshiva in Yeshiva University, somebody extraordinarily senior. Not anybody who I’ve mentioned and not anybody who’s been on our podcast, but I called up somebody who I have an extraordinarily close relationship to, because I knew the wagons were circling to get me out. And this Rosh Yeshiva, who was extraordinarily kind and generous, and gave me so much chizzuk, so much encouragement during that period. I’m really grateful to them. They made a Talmudic distinction about cancel culture, and it’s similar to what I just mentioned. He used brisker terminology that really originates in the Talmud itself. He said, “David, are they after the cheftza or the gavrah?”

He said that when this person called me and was looking to get you fired, I posed them the following question: Are they after the cheftza or the gavrah? What’s the difference between the cheftza or the gavrah? The “cheftza” is the object. That’s the Hebrew word meaning the object of the scorn. You wrote an essay people don’t like. You recorded an interview that people think are inappropriate. You tweeted something. You can call something out as being inappropriate. That is tried and true, and there are boundaries for appropriateness that I think all of us need to do our best to adhere to. That’s the cheftza question. But he said, if you’re after the gavrah, if you’re after the person, if you’re personalizing it, and you’re saying that this person is corrupt because they made a mistake, that’s not something I’m willing to get on board with.

I think I noticed the difference. I think the difference always is of whether or not you’re after the object of the content, the idea that you deem inappropriate, or the person that you want to just remove entirely from the community. Usually the difference is that you find throughout history, and I have found this personally, is whether or not they approach you personally. If somebody has a personal relationship with you, and they see that you shared something that was inappropriate or that they didn’t like or that they vehemently disagree with, they usually reach out to you personally. When they start reaching out to others and don’t give you a chance to either delete, apologize, you made a mistake – I’ve deleted, I’ve made mistakes – but they start circling the wagons and trying to get your employers to get you fired or ensure that people stay away from you, that’s usually a fair indication that they are not after the cheftza. They’re not after the object, but instead, they are after the gavrah.

And I think it’s those type of wars that have a great deal of capacity to corrupt, even when justified, those who wage it. So I think this month, there are some really important questions that we’re going to be asking, not just what we’re seeing happening on, whether it’s on campuses or in just broader society, this movement of cancel culture and censorship of making people accountable and responsible for the things that they shared in ways that aren’t always proportionate to what was shared. We’ll be talking a little bit about that, but there’s also a question for within our community, the way that we look, and I think that there are essentially three questions that we’re going to be exploring over the course of this subject.

The first question is, what kind of history should we share? This is a question that we’re seeing now in American history in particular in the way that we look at the monuments of figures and past history. Whether it was people who fought with the confederacy, whether it’s the notion of founding fathers being slave owners. This is something that we see in broad secular culture. But I think it provokes some really important questions about our community, about the Jewish community, about figures and rabbinic leaders from the past, who perhaps their legacy is a mixed barrel.

There are stories that involve them and involve previous great Jewish leaders that maybe don’t measure up to the current values of the Jewish community. How should we look at those aspects, those moments in history of those previous leaders? Should we censor those stories? Should we broadcast those stories? Should we whisper them quietly, like we do some other passages in Jewish life? We sometimes whisper when we don’t totally have the capacity to say it loudly. You whisper it. What’s the right way that we should look at those moments and those personalities from our own history that don’t necessarily measure up to the conceptions of the Jewish community that we have now?

I think a second question that I hope that we will return to is, how should we react when we see and learn things that we don’t like or approve of? What’s the right way to do it? What are the things that we should litigate and speak out upon? And what are the things that, maybe this isn’t the right place to raise this issue? Maybe this isn’t the right approach to correct something that we found inappropriate? And finally, what should we share about ourselves? What should we disclose? What should we share about our own Jewish stories, whether or not you’re a Jewish educator or a rabbi or whatever it is? Everybody is a role model to somebody. And the question is, which parts of our own lives should we be sharing?

And that’s why I am so incredibly excited for this topic, which I think the relevance of this topic in this moment is almost the ancillary part of our discussion, and what I want to more closely examine are what are the implications and ways these concepts, cancel culture, censorship, are manifest within our own community? So we have an incredible lineup this month of personalities and people who really are at the center of this intersection of how ideas of cancel culture, censorship, the way that we transmit our values, the way we transmit our history, how should those ideas intersect?

And that is why I am so excited for our first conversation with Altie Karper. If you have never heard of Altie Karper, you almost certainly have heard of her books. She is the editor of Schocken Press, Schocken Publishing, which is an imprint of Knopf, which is one of the most storied Jewish publishing houses in the world. She runs Schocken, and she says she is Schocken. It’s a small shop, but she does incredible things with it. They have published the works of Rabbi Sacks, they’ve published works on Russ and Daughters, you can find a lot of their amazing stuff online, and we’ll be sure to link to all of that.

What we’re really talking about is one book that she published well over a decade ago, nearly two decades ago, called One People, Two Worlds, which was a book that was a dialogue between an Orthodox Rabbi, Rabbi Yosef Reinman, and a Reform Rabbi, Rabbi Eric Yoffie. And they had a dialogue in this book, and right when they were about to go on this press tour to publicize the book, there were people calling and saying that this book was not appropriate. It kind of muddled to have a dialogue between two different denominations at the time in some segments of the Orthodox world was deemed inappropriate.

They had to withdraw from the book tour. And Altie, as she recounts in this incredible interview, takes us through how this happened, how she reacted, who she called to respond, because she, as an Orthodox woman, was forced to defend this book, which she thought she had all the approvals for, and then needed to explain to all of her secular or non-Orthodox partners, she had a whole bunch either from the publishing house or from all the JCCs around the country who had lined this up, exactly what had happened.

She remains a major part of the Orthodox community. She still lives on the Lower East Side and has been a staple of that community for many years. Altie is really an incredibly thoughtful person. And just one thing I want to mention, which I found so special about Altie’s participation in this interview, is that Altie refused to be interviewed until I reached out and got permission from Rabbi Reinman, who so much of this controversy surrounded. And number one, it speaks to the graciousness of Altie, that she doesn’t want to rehash an incident that casted one of her authors in a bad light, or jeopardized his standing in the community, but I also think it’s a testament to the graciousness of Rabbi Reinman, who I did reach out to, and was so kind and so gracious.

He did not want to come on to this interview, which I absolutely understand. He prefered to focus on other works that he’s putting out now, and he’s an incredibly prolific author and publishes books both for the popular audience and more scholarly, rabbinic works. He has an incredible book on Shtaros, on Jewish legal documents that you can find. I don’t know how many of our listeners are interested in that, but he is an incredible author, and he was incredibly gracious as well. But this was a major incident in the Jewish community. It got coverage from the New York Times, and reliving it through the perspective of Altie, how this affected her personally as a Jew, how this affected her outlook on the way the community reacted, and how she ensured that the reputation of the book, of the publishing house, and most importantly her authors, remained intact. It is my absolute pleasure to introduce our conversation with Altie Karper. Altie, thank you so much for taking time to speak with me today.

Altie Karper:

My pleasure.

David Bashevkin:

So Altie, what we’re talking about today is your role in a fairly well known controversy to people who are old enough to remember it. There was a book published nearly 20 years ago, I believe it was 2003, and it was called One People, Two Worlds. I have it right in front of me.

Altie Karper:

2002.

David Bashevkin:

- So we’re really coming up on 20 years, the 20th anniversary. And it’s called One People, Two Worlds.

Altie Karper:

Yep.

David Bashevkin:

It’s a dialogue between a Reform rabbi and an Orthodox rabbi, Ammiel Hirsch, Yosef Reinman, and they explore the issues that divide them. And before we get into the controversy, maybe we could start at the very beginning to talk about, what was your role in this book, and how did you first hear about it?

Altie Karper:

This was a project that was submitted to me by a literary agent named Richard Curtis. It was actually submitted to a colleague of mine at Schocken who was not really familiar with the Orthodox world and Orthodox vis-a-vis Reform. And it came to her from a literary agent who was a friend of hers. She got the proposal, and she said, “Well, what do you think Altie? Is this something we should be doing at Schocken? Would anybody be interested in reading this?” And I read the proposal, and I was just blown out of my chair, because Rabbi Reinman was clearly an Orthodox rabbi. He was clearly from Lakewood. And he was obviously willing to participate in… We didn’t really call it a dialogue, we called it an exploration, an exploration with a Reform rabbi. And I just thought this was absolutely astonishing. I mean, I couldn’t believe that he would have agreed to this without getting the necessary haskamos from his religious authorities. And I said, well, if this –

David Bashevkin:

Haskamos meaning rabbinic approbations, correct?

Altie Karper:

Right. Rabbinic approbations, right. And I said to my colleague, “If this guy’s for real, and if he has all of the rabbinic approbations that will satisfy me, then we have to publish this book. This is unprecedented. This is absolutely amazing.” So we did determine that Rabbi Reinman had all of the haskamos, the approbations that he needed, and we signed up the book. It wasn’t anything that people at Random House were particularly excited about because they were not aware of how monumental a book project this was, but we did try to communicate the enthusiasm, and eventually, people at the sales force got it. And my publicity colleagues got it.

Then when we pitched the book for publicity to outside venues, then they were able to see how truly momentous this was, because practically every Jewish community center in the United States was interested in having these two rabbis come and do events at their Jewish community center, their synagogue, their whatever. So we booked a 17-city book tour. It was going to kick off with an appearance at the 92nd Street Y. I mean, it was just the dream tour. Every single venue that I would’ve loved to have to promote this book was interested in doing it. At some point during the publication –

David Bashevkin:

Before we get into the actual controversy, I want to take one further step back and just explain two things. Number one is, what is your role at Schocken? And two, maybe situate yourself, how did you know, maybe explain to our listeners, how did you know to look at that this would need rabbinic approbations? Meaning, you are identified, you grew up on the Lower East Side as an Orthodox Jew, but tell us, what’s your role in Schocken? And where do you situate yourself in the Jewish community?

Altie Karper:

I’m the editorial director of Schocken books. We are an imprint of what is now known as Penguin Random House, what was known at the time as Random House. It’s a big international English language, and actually multi-language, publisher. And we are Schocken books, it’s a very small imprint within this huge corporation, and our specialty is books of Jewish interest: fiction, non-fiction, history, biography, culture, pop culture, cook books. I mean, you name it, we do it. Anything having to do with the Jewish experience. So that’s what I do. As far as my background is, I’m a nice Bais Yaakov girl from the Lower East Side. Also attended Teacher’s Institute for Women at Yeshiva University, and Bruriah in Israel for my time in Israel.

I have a pretty good Orthodox Jewish background, and fully cognizant of the feeling of Orthodox rabbinic authorities on dialogue with non-Orthodox groups. And I’m aware of the Rav zt’l, his ruling about the Synagogue Council of America. I mean, there were a lot of things that have been published over the years, starting, I guess, in the 1950s, about how Orthodox rabbis should approach contact with rabbis who were Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist, Humanistic. So I had that background. I knew that this was a big deal, that this was an Orthodox rabbi who was willing to have a public conversation with a Reform rabbi, and I wanted to make sure that there were enough Orthodox rabbinic authorities who were on board with this. I didn’t want to publish something that would then get excoriated by the Orthodox community. That wasn’t my intention. My intention was to publish a book that people would read and that people would learn from. So that’s the background to that.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning in general, and I’m just curious, and maybe we’ll talk more about this, but before we get into the controversy, in general, as an editor, and you grew up in the Orthodox community, you grew up in the same community as Rav Moshe Feinstein. I’m sure you saw him from time to time.

Altie Karper:

Oh, yes.

David Bashevkin:

Who’s also very instrumental. And I’m just curious, generally as an editor, and I just want to make a disclaimer to our listeners. Though Altie is at the top of this Jewish publishing empire of Schocken, which is the big fish in the small pond of Jewish publishing, I would not advise you to send her your manuscripts, because even family doesn’t get special treatment.

Altie Karper:

Thank you for that.

David Bashevkin:

Be careful. Don’t just send her your manuscripts. But before we get into the controversy, let me just ask you, your grounding as an Orthodox Jew, how does that shape the way that you look at the books that you publish? Meaning, you know the sensitivities that emerge in the Orthodox community. You identify and are immersed in that world. So how does that play out when you see a manuscript that has something that is not for the orthodox community?

Altie Karper:

Well, my audience is not specifically Orthodox Jews. My audience isn’t even specifically Jews. My audience is anybody who wants to read a book of Jewish interest that I think would appeal to a large segment of readers, whether they’re Jewish or not. Well, actually, I’m interested in publishing books that entertain, challenge, and inform. Those are the three things in the Jewish realm. Which is to say, that’s why I publish pop culture. That’s why I publish history. That’s why I publish books where a Reform and Orthodox rabbi are in conversation. I’m interested in books that I think my readers would be interested in about all realms of the Jewish experience.

There are things that I would not publish because I’m a frum person, but that decision is left to me by the corporation. I mean, would I publish a book of Jewish pornography? Probably not. I probably wouldn’t publish a book of Jewish pornography even if I wasn’t a frum person. My mandate is to publish books that I feel comfortable with.

David Bashevkin:

Altie, take me through now, you have this amazing manuscript, you have this book. You have all the rabbinic approbations that you need lined up. And at this point, you probably have a nice relationship with both authors. Let me ask you, at what point did you discover that there was a controversy surrounding this book more than the normal readers saying, “Ooh la la. This is something we haven’t seen before.”

Altie Karper:

Well, that’s actually very interesting because it interestingly enough didn’t come from Rabbi Reinman. It came from a second cousin of mine whose sons and/or sons-in-law learned in Lakewood. And this cousin, whose name also happens to be David, calls me up at the office one day out of the blue. And this is a guy that I see a couple of times a year at family weddings and who’s never called me at the office. And he called me, and he said, “Altie, they’re out to get your book.” And I said, “What are you talking about?” He said, “You’re publishing that two rabbis book, right? Because I see it’s from Schocken.” I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “Anonymous papers are being hung up on the Beis Medrash in Lakewood that this book, no one is to go near this book.” And I said, “Well, that’s interesting.”

And I called Rabbi Reinman, and I reported to him what my cousin told me, and he said, “Yeah, there’s a little bit of an issue, but I’m handling it.” So I said okay. And this was probably… Okay, we published the book in August. So this was actually probably in June because, I’ll explain why in a minute. So he said, “No, I’m handling it. It’s okay. There were some murmurings, but everything’s going to be okay.” And then maybe a couple of weeks later, he calls me and he says, “Is it too late to make any changes in the book?” And I said, “Well, what?” He said, “Well, I’ve got to take out one of the people in the acknowledgements because he’s a little reluctant to be associated with the book.”

I’m not going to mention any names, that’s not why I’m here. I said, “No, it’s not too late. The book’s about to go on press. We can take out his name.” And I kept saying to him, “Are you sure we’re okay here?” And he said, “Yeah, yeah. It’s fine. There are some issues, but I’m handling it.” So we took out that name, and we published the book. And then we had our tour set up, and the first… And I’m trying to remember the exact chronology. Rabbi Reinman, at one point, and I guess it was in September. No, it was very close to when the tour was going to start. And he said, “Well, I’m having some issues, and I might have to cancel some tour cities.” Then I’m starting to get nervous.

Our kickoff event was 92nd Street Y. We did the event, and it was an amazing success. And the moderator was a Conservative rabbi. He was the director of Judaic programming at the time at the 92nd Street Y. And I remember, he asked Rabbi Reinman the most amazing question. This was during the heyday of The Sopranos. And he said to Rabbi Reinman, “If somebody asks you, ‘Should I learn Torah, or should I learn Gemara with a Reform rabbi, or watch The Sopranos?’” And you can just hear a pin drop. It was electrified silence. And they had just had a perfectly nice sort of kumbaya, touchy-feely kind of event, and then this rabbi drops this question. And there’s silence. And Rabbi Reinman takes a deep breath, and he says, “You should watch The Sopranos.” It was about 500 people in the 92nd Street Y in the Kaufman auditorium, and this huge intake of breath. It was just electrifying.

David Bashevkin:

I’m not sure. I wonder if that is an indictment on Rabbi Reinman’s view on learning Talmud with a Reform rabbi or his deep appreciation of the quality of The Sopranos. I guess we may never know that. At this point, you had the 92nd Street Y event, which is a great kickoff event. I mean, my dream kickoff event is the YU Seforim Sale. So the 92nd Street Y is definitely a step up from that.

Altie Karper:

And then what happened, there was a couple of days hiatus and the tour was going to start. And then, I don’t remember exactly how I became aware of it because I don’t have my book files. I’m working from home. I don’t have my book files. I have them in the office. But this proclamation came down from Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. And it said that there’s this book that’s being published that’s a conversation with an Orthodox and Reform rabbi, and this book should be kept far away from any observant home. That this was a terrible idea, and it gives legitimacy to… I don’t know if they actually used the word “Reform,” I don’t remember what the exact language was, or “apikorsim,” I don’t remember what they said.

David Bashevkin:

I have the exact language.

Altie Karper:

Oh!

David Bashevkin:

I have the exact language in front of me.

Altie Karper:

Oh, you have it?

David Bashevkin:

Where it says, “A distressing development has occurred in our community. The publication of a book that presents a debate between on the one hand, a faithful Jew and talmud chacham,” meaning a scholar, “and on the other, a Reform leader whose premises reflect his denial on the very basis of our faith. The entire gestalt of the book and its promotion, including the strong public emphasis on the warm personal interaction between the two authors, and joint promotional appearances before large audiences, represents a blurring of boundaries between darkness and light and an undermining of the Jewish religious tradition.” What did you feel when you got the first reports about this? And explain the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah for you. You grew up knowing what this kind of centralized rabbinic body is?

Altie Karper:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

You grew up knowing one of its most senior members, I have mentioned earlier, Rav Moshe Feinstein. You have memories of him on the Lower East Side. So how did you feel personally when you first read this?

Altie Karper:

Well, I had this horrible sinking feeling in my stomach. I was just gobsmacked. I mean, that’s the word. I had not anticipated this at all. I was just speechless. I was speechless because this was not my intention in publishing this book, and I was speechless because I had a 17 city author tour with 100s of books purchased by these venues that the authors were going to sign. These venues had been advertised in bulletins, in local newspapers. So I had a responsibility to Random House. And I also, as a member of the Orthodox community, it was just not my intention to do something that made Orthodox rabbinical establishment upset. I was just gobsmacked. It was just something that I had not anticipated at all.

So Rabbi Reinman, after this proclamation was published, Rabbi Reinman called me and said, “I can’t go out on tour. I’m sorry.” So then I really started to panic. I mean, I didn’t know what to do. This was going to be terrible. In addition to bad for Random House, it was going to be a huge, I felt, chillul Hashem, because here’s an Orthodox rabbi who made a commitment to support his book and signed a contract, and in the contract it says that he agrees to do publicity for the book. And now it appears as though he’s backing out. I mean, I completely understood why. And I was chas v’shalom not going to hold him liable. He was technically in breech of contract, but I was not going to pursue any options in that area.

I just didn’t know what I was going to do with 17 cities that thought they were going to be getting two rabbis, and now I didn’t know what they were going to be getting. So while I’m sitting there trying to figure this out, I know this is going to be your next question, so I’ll just get to it. So I get a call –

David Bashevkin:

Hey, you’re jumping right in there, because you told me this.

Altie Karper:

I’m jumping right in. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

But it tells a little bit, to give the context, meaning your next call was so fascinating, maybe just give us a little bit more context, not just to the call and who you turned to, but there’s a deep family relationship that you had with a sitting member on the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. Maybe tell us about what that relationship was and what that call was.

Altie Karper:

Right, okay. Well, I’ll set it up. So I’m sitting at my desk. The first thing I have to do is tell my publicist that the tour is off. And the next thing she’s going to say is, “Okay, so what do we do? Do we cancel the tour?” This never happened to me. So I was just gobsmacked. And while I’m sitting there thinking about what we’re going to do, can we save this tour? So I get a phone call. It’s from Gary Rosenblatt, who’s the publisher of the New York Jewish Week, and he said, “Well, we’re about to run the story about the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah banning this book that was written by an Orthodox rabbi and a Reform rabbi that you are the publisher of, and I’d like to know if you would like to give me a comment.”

In addition to everything else I was worrying about, now I have to figure out what I was going to say publicly. So the first thing I said to him was, “Well, Gary…” And I knew Gary Rosenblatt. We were acquaintances. And I said, “Gary, you know that I’m a nice, frum girl. And you know that I cannot give you a response to this without consulting my rav, because this is pretty huge. So I’m going to ask you if you can just give me a little time to call my rav and find out what is an acceptable thing to say to you. Because this is something that’s bigger than just a censorship issue. This is bigger for me personally. It’s bigger for the Jewish people. It’s bigger for Orthodox Judaism. So you got to give me time.”

He said, “Yeah, sure. I get it, fine.” So having been in publishing, by that point in time, I guess I had been in publishing about 20 years. So periodically, things would come up, shailas that I would ask, and for the huge ones, I would turn to Rav Dovid Feinstein zetzal, who lived down the block from me.

David Bashevkin:

Who was a member of the Moetzes?

Altie Karper:

Of the Moetzes, right. So I would turn to Rav Dovid –

David Bashevkin:

Can I just ask you Altie? When Rav Moshe was alive, did you also have a relationship with his father, Rav Moshe Feinstein?

Altie Karper:

No, my dad had a relationship with Rav Moshe Feinstein. They were on committees together. They were on advocacy committees together. When Rav Moshe was niftar, I was just starting out in publishing. So the only personal contact I had actually with Rav Moshe zetzal was when we were sitting shiva with my father, and Rav Moshe came up to be menachem avel. Which, talk about being gobsmacked. And what was interesting, he came up during the afternoon, when there were not people there, and he came up, I believe he was there, he came with Rav Dov and some other men. And they sat down, and it was me and my mother and my brother and my uncle Shmiel, who were sitting shiva, and we all would… And there was nobody else there. And we all sat down, and of course Rav Moshe, of course he knew the Halakhah, which is that you don’t start speaking until the avel starts speaking.

And nobody could think of what to say. So finally my uncle said [inaudible], and that was enough for Rav Moshe. The avel had spoken first. So then he proceeded to say all kinds of nice things about my dad, which was huge. And he was basically in dialogue with my uncle and with my brother, and I was sitting off to the side, and then he got up to leave, and he stopped where I was sitting, right in front of me. And he said, “You’re the daughter?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Your father was a finer man.”

David Bashevkin:

Wow.

Altie Karper:

And I can’t tell you how many people who would come to see my brother would just walk past me, like I wasn’t in the room. And he stopped and made a point to actually say something, words of nechama, to me personally. And that was just one of the signal experiences of my life. So, I mean, that was the only personal contact that I ever had with Rav Moshe zetzal.

David Bashevkin:

But Rav Dovid you knew?

Altie Karper:

My brother was a talmud of Rav Dovid at MTJ. So, when I went into publishing, and I would get questions that I knew were like, big enchilada questions, so I would say to my brother, “Do you think I could ask Rav Dovid this?” My brother would say yes, like maybe the first couple of times my brother would call him and say, my sister has a shaila. And then after a while, my brother said, you could just call them. So, I knew I could do that. And I knew that this was a pretty big enchilada, and I would have to call Rav Dovid about this. My go-to rav for shailas, Rabbi Yeshaya Siff, who’s rabbi of Young Israel of Manhattan. And he has been my rav since I was a child, when he came to the Young Israel, but I knew that there was some shailas that he would say, Altie, you need to kick this up a notch. And I knew which ones they were. So I would just go to Rav Dovid for those.

David Bashevkin:

And this was certainly one of them?

Altie Karper:

This was one of those. So it was during the day, and I didn’t know where he was. But I had to call immediately, and I didn’t want – Usually when I had a shaila for Rav Dovid I would call him when I knew he was home in the evening. I wouldn’t dream of bothering him in the beis midrash during the day. But Gary was on deadline, and I just had to call, I think it might’ve even been like Friday or something. I don’t remember. So I called the home and I got Rebbetzin Malka, and I explained to her what my problem was. And I figured that she would then call him at the beis midrash and explain the problem, and then she would call me back with whatever Rav Dovid said I should do.

After she heard the whole shpiel she said, Altie, you need to speak to the Rosh Yeshiva directly. Is said, meet him in the beis midrash? She said, yeah. And she gave me this number, which is what I call the bat phone, because this was obviously, this was the number that you call if you needed to speak to Rav Dovid and it was an emergency. So she said, and tell, whoever picks up, say that I gave you this number. So I did that. I called, and this person picked up, and I identified myself. And I said, I have a shaila for the Rosh Yeshiva, and Rebetzin Malka gave me this number and said you should put me through to him. So he did.

I got Rav Dovid on the phone and I tell him the whole maysa. And I said, bottom line is, I just need some direction on how to reply to Gary Rosenblatt, because I mean, I’m upset. I’m certainly upset on behalf of Random House. I’m upset. But I can’t say that, I have to represent my company, which is upset. But I don’t want to say anything that’s mechutzafdik.

David Bashevkin:

Disrespectful.

Altie Karper:

Yeah. I don’t want to say anything disrespectful, because they are a rabbinical [inaudible] and this is their ruling, and I’m a frum person and I accept their ruling. But on the other hand, I’m an employee of Random House and Random House is very upset about this. So we worked through blank. I mean, it was just surreal to me. We worked through… It was like I had a thesaurus in front of me, and we were just looking for like the proper adjective, the proper adverb. So we finally came up with a one line set statement, which was speaking on behalf of Random House. “We are puzzled as to how a book that was rabbinically acceptable six months ago is now not rabbinically acceptable.” We are puzzled. And he said yeah, okay. You can say “puzzled”. So that was when I called up Gary. I said, “Okay, Gary, get a pen. Here’s my statement.”

David Bashevkin:

It’s just remarkable to me. And I really think it’s one of the lesser known footnotes in this story, but that Rav Dovid Feinstein, who sat on the Moetzes, and I’m sure was aware and played a role in explaining why he felt this book was not appropriate for the community that he was leading at the time, but also took the very same time to walk you through a healthy statement, like serving as your PR agent in talking about this. I always found that story fairly moving, but tell me now, in the aftermath, after you share that it was puzzled, how did you then explain this to the publisher and the conversations that you had inside, and what residual feelings did you have with yourself? I mean, you’re still affiliated with the very same community. You don’t seem to me, I mean, we know each other for so many years, you don’t seem to me that you’re bitter or cynical or you didn’t leave the community over this. Did it in any way affect your affiliation or connection to the community and if not, why not?

Altie Karper:

Well, what I found out much later, and I just found this out, by happenstance, was… Actually, I was in the local butcher shop, and this man walks in and I recognize him to be someone who was affiliated with Rav Dovid at MTJ. And we’ve also known each other casually. And he said to me, “I just want you to know something about that book.” I had to think for a minute what book he was referring to. And I said, “You mean the two rabbis book?” He said, “Yeah.” He said, “You should know that the rabbis who wrote that proclamation, they went to Rav Dovid to get him to sign it, and he wouldn’t sign it. And he said that he didn’t agree with that. And his reasoning was, it had to do with the motivation.”

He said, “Rabbi Reinman’s motivation was to make a kiddush Hashem, Rabbi Reinman’s motivation was to spread Yiddishkeit, to make people frum. He was not doing it to because he disagreed with the decision by Orthodox authorities to not dialogue with Reform rabbis. He didn’t do it for that reason. And he did go through the process of explaining what his book was and what his motivation was. And he got approvals. He wasn’t doing this to test boundaries, to be mechutzef, because he disagreed with the Moetzes. He did this from the purest and most altruistic motives.” And so Rav Dovid would not sign that ban. So that really restored my faith, whatever my faith needed to be restored. And also the fact that Rav Dovid Cohen, Rav Dovid Cohen from Congregation Gvul Yaavetz. He actually gave me a blurb for the book.

David Bashevkin:

It’s on the back of the book. I have it right in front –

Altie Karper:

Yeah. And people went to him to ask him to take his blurb back. And he said, absolutely not. And he said, he said the most gevaldig, the most amazing thing. He said, and he told me he’s the rav of a number of my cousins who daven in his shul. So I know him from seeing him at family simchas. So he said to me, they came to me and they asked me to take my haskama off, and I said to them, if you show me one Orthodox Jew who’s going to become Reform from reading this book, I will take my haskama off. He said, I’ll go you one better. He said, if you show me one frei yid, one secular Jew who became Reform from reading this book, I will take my haskama off. And he got a lot of grief for that, but he stuck to his guns. So yeah, I mean, there were a lot of reasons, I didn’t take this as this monolithic Orthodox community coming down against this book, because that’s not what we are. I mean, we’re in galus, we don’t have a monolithic Orthodox community.

David Bashevkin:

You just mentioned on how you remained connected to the Orthodox community even after this stress of feeling that the very community that you’re trying to serve was not interested, actually quite opposed to what you did. Tell me a little bit about how the book reacted, meaning the book, the sales of the book reacted to this ban. Meaning, you lost the book tour. They didn’t go, they didn’t after the 92nd street Y continue on their tour. But it was covered in the New York Times and the Jewish Press and all the Jewish media. What ended up happening to the sales of the book? Did they absolutely plummet because it was banned and no Orthodox Jews were buying it? Did sales nosedive that you only sold a handful of copies because they no longer went on this tour?

Altie Karper:

Well, actually, we didn’t cancel the tour. My publicist said, “We’re not canceling this tour. How about if you go out on tour with the Reform rabbi?” Which took me aback, because that’s not what editors do. Editors sit at their desks and edit. We don’t go out and pound the pavement and sell the books, but I didn’t want to lose the sales. And I didn’t want Rabbi Hirsch to go out on his own because it would have been kind of a non event, and what the event became instead of an Orthodox and Reform rabbi talking about their book, it became events about the controversy. And what I was trying to do, and I was trying to do two things. I was trying to keep this whole thing from being a chillul Hashem, and I wanted to do a little bit of what Rabbi Reinman wanted to accomplish. I agreed to go out on some of the 17 cities. I went to the cities on the Eastern – I mean, I had a long conversation with my mother, who was not thrilled about any of this.

David Bashevkin:

Like a good Jewish mother.

Altie Karper:

The compromise was I would just go with Rabbi Hirsch to the East coast cities. So we did a couple of events in New Jersey. We did an event in Washington DC. We did an event in Connecticut. I forget where else. We just did the Northeast corridor. And Rabbi Hirsch went, he did… We had other cities. We had California, I think. And we had Detroit and we had someplace in Texas. So he did those on his own. So we were able to salvage the tour, and there were a lot of angry people at these events because actually, I mean, the audience that Rabbi Reinman was speaking to was not Orthodox Jews. It was people who were neither Orthodox nor Reform. He was trying to say… He wanted to be mekarev people with this.

David Bashevkin:

To do outreach.

Altie Karper:

That was his intention, to do outreach. He wanted to do outreach. And he knew, and he’d said to me on numerous occasions, if I had submitted a proposal to Random House on this Orthodox rabbi, and I would like to do a book of outreach to a non-observant Jews, you would not have signed that up. And I said, “You’re exactly right, because that’s not what I do. I’m not an evangelical press.” So he said, when this opportunity came to partner with this Reform rabbi, he said, “I knew that this would give me the platform that I could use to speak to unaffiliated people and explain to them what Orthodox Judaism was.”

He said it was not my intention, and that’s not what the book is about if you read the book. It’s not a debate between an Orthodox and a Reform rabbi. He’s not knocking down Rabbi Hirsch’s arguments. He is just presenting. What is the Orthodox point of view on this? What do Orthodox Jews believe on that? And that was because it was a series of letters, that’s what the book is. And his letters were, okay, let’s talk about… This is so long, let’s talk about kashrus, kosher. This is the Orthodox view of – this is the Orthodox view of life after death.

This is the Orthodox view. And then Rabbi Hirsch’s responses would be, well, and this is the Reform view, and Rabbi Hirsch’s point was that it’s not quite that far from the Orthodox view. Which is, yeah, I’m not making any value judgements here. But they actually had two different purposes in writing the book. Rabbi Reinman’s purpose in writing the book was to introduce Torah Judaism to people who did not know anything about it. Rabbi Hirsch’s purpose in writing the book was to show that Reform theology is not that far away from Orthodox theology.

They had two different purposes. And I was keen to keep rabbi Reinman’s vision of the book. So that was why I went out on tour when I was able to with Rabbi Hirsch and just try to undo the damage that the ban did, because what this was doing was the exact opposite of what Rabbi Reinman’s idea for the book was. I mean, Rabbi Reinman wanted to make a kiddush Hashem, a sanctification of God’s name with this book. He wanted to show people the glories and the wonders of Orthodox Judaism. And what this whole thing did was actually put a very bad taste for Orthodox Judaism in people’s mouths. And my interest was that that not happen. So that was why I went out on tour.

The interesting thing was that audience members who would attempt to dump on Rabbi Reinman would find that he was being supported by Rabbi Hirsch. Rabbi Hirsch stuck up for him and said, I understand why he had to do this. And he’s still my friend. And I would have loved to go out on tour with him, but I still love him. And he’s still my friend. And I understand why he had to do this, which I thought was very admirable of Rabbi Hirsch. They still keep up to this day, by the way. So, an answer to your question about how… Yeah, well, there’s nothing like telling people that they can’t read a book to make them want to read it. This book probably sold several thousand copies more than it would have sold had it not been banned. And it’s sold in communities that we didn’t think was going to buy it, it’s sold in Orthodox communities. And we weren’t really thinking it was going to sell in Orthodox communities because we didn’t think Orthodox Jews would be interested reading it. And it sold at, I’m not going to name the stores, but we’re Random House. We know who we ship our books to and we know who sells them because they report back to us. So this book sold –

David Bashevkin:

It’s not a mom and pop shop. You have some data on this?

Altie Karper:

Yeah, that’s right. Exactly. So we knew that it sold in Monsey and it sold in Flatbush and it sold in Borough Park. We know where it sold. And it was, I mean, it was under the table, but yes, it’s sold in much greater numbers in these communities than it would have had it not been banned.

David Bashevkin:

If you were giving advice, and I have published books, your experience is that a book ban may actually increase sales of the book? I know when I published, I tried it to align. I also got rabbinic approbations, but I also tried to line up a few rabbinic bans to hopefully drum up some sales of my own book. I couldn’t get any in line. One thing that I want to talk about is the later aftermath. And I want to just mention this to our listeners that I found quite moving, is that you did not agree – this was an uncomfortable chapter in your own life, and you would not agree to come and sit down with me to talk about this before getting permission from Rabbi Reinman.

He was extraordinarily gracious. He wasn’t interested in speaking himself, but he said there was no problem in recounting this, which I thought was really wonderful. So let me ask you, in general, we’re living in a society right now where there is a great deal of attention on what people call cancel culture, what people notice from maybe the more left wing community of this allegiance to the purity of ideals, and people who don’t reach those ideals, they immediately want to cancel book agreements and this and that. As an editor in Schocken, how do you look at manuscripts, at books, and other publications from Schocken, not just this one, in light of this renewed attention that’s being given to, so to speak, cancel culture?

Altie Karper:

That’s an interesting question. I publish books that interest me, that intrigue me, that I feel I learn something from. Regardless of where they are on the ideological spectrum. And that’s my bottom line. I publish books that inform, that contribute in a meaningful and respectful and intelligent way to dialogue. I don’t look at books, whether they’re right wing or left wing. I just look at books that have intelligent and interesting and fair-minded and nondoctrinaire ways of saying what they want to say.

David Bashevkin:

Have you ever rejected a book in advance because you felt it was too incendiary, subversive? Have you ever edited parts out of one of your authors manuscripts because you said, this is not going to play well in our readership? Not because of grammar issues or typos, but the substance, there are parts of this book, almost as like a censor, for their own good. Have you ever played those roles as editor?

Altie Karper:

No. That never came up.

David Bashevkin:

Not once?

Altie Karper:

No. I published a book by Deborah Lipstadt on Anti-Semitism, and it’s called Antisemitism: Here and Now. And what attracted to me to Deborah’s book is that, this is an equal opportunity offender. The people on the right are guilty of antisemitism and people on the left are guilty of antisemitism. And what I admired about her book was the she pulled no punches and identifying right wing antisemites, and then identifying left-wing antisemites. And that to me is the ideal publishing experience.

David Bashevkin:

One thing before we close, and we always close our interview with quick questions, but I wanted to mention this as well. We spoke, when Rav Dovid, who you had a relationship with, passed away, we all know he passed away right around the same time as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. And you are one of the few people that I know of in the whole entire world who had relationships with both of them. You were the editor of Rabbi Sacks’s book. I believe it’s called To Heal a Fractured World. And you had worked with him. He also went through a controversy of having one of his books need to be revised. There were people calling on banning it. Did you ever speak to Rabbi Sacks about his experience with that?

Altie Karper:

Yeah, that was not a book that I published. That was The Dignity of Difference. I published To Heal a Fractured World and a Future Tense, Not in God’s Name, and the book about the science and religion.

David Bashevkin:

The Great Partnership?

Altie Karper:

The Great Partnership, right. Those are the four books that I published. The book on The Dignity of Difference I did not publish. And Rabbi Sacks just treated that as a question of semantics. He revised what he said in the book for subsequent printings, but I mean, I’m not going to speak for him, but he felt that the way he revised the book did not change how he felt on the subject about which he was writing, and that it was just a question of semantics. And I’m not going to say anything else because I’m not going to speak for Rabbi Sacks zetzal, and it wasn’t a book that I published, but he felt very strongly about that.

David Bashevkin:

The one thing I do love that you mentioned about Rabbi Sacks is he made your role as an editor fairly easy, more so than maybe any other author. You had mentioned that, that…

Altie Karper:

Yeah, he didn’t need editing. If all my authors were like Rabbi Sacks, I’d be out of a job. And it was really interesting, because his books were published first in the United Kingdom, and then we published them in the U.S. and I had occasion to meet once in England with his UK editor. And I complimented him on his editing of Rabbi Sacks’ books. And he said, “Well, I don’t edit them. I thought you edited them.” And I said, “I didn’t edit them. I thought you edited them.” So there you go. He just, Rabbi Sacks didn’t need an editor.

David Bashevkin:

Altie, I cannot thank you enough for your time. And this story. And the example that you play in the world of publishing is just an incredible example, I think for all Jews, and a real inspiration. It’s not a surprise to me that you continued the tour as an example of what it means to be an Orthodox Jew. You certainly bring me inspiration. I always end the interviews with a little bit of quicker questions, rapid fire questions. My first question is, somebody was looking for a book about the writing process or publishing. What is the editing process like? What is a book you would recommend for somebody to understand what the process of writing and editing is all about?

Altie Karper:

Okay. That’s an interesting question. Actually, al regel achas, on one foot, I can’t come up with it. I mean, there is a book that I’m thinking of, but the title of it isn’t coming to mind. I don’t even know if it’s still in print. I’m going to have to get back to you on that, because I mean, there is a very nice book that might not even be in print, but you can get it on a used book site, which is a guide for novice writers. I’ll have to get back to you on the title of that, unless it comes to me…

David Bashevkin:

No problem. My next question, I always ask my guests. If somebody gave you a great deal of money and allowed you to take a sabbatical for as long as you needed, go back to school, get a PhD, or write a book. What do you think the topic of that book would be?

Altie Karper:

Well, what fascinates me is Yiddish literature that was written by women during the time that Shalom Alechem and Yud Lamed Peretz and Ansky and Mendele Mocher Sforim were publishing works. There was an extraordinary amount of books written by women. Isaac Bashevis Singer’s sister, [inaudible], those are two that immediately spring to mind. And it’s all there. It’s in the archives of the National Yiddish Book Center. So what I would like to do is I would get my PhD in Yiddish literature and then go into, dive into those stacks and see what I could translate.

David Bashevkin:

Can you translate Yiddish? Do you speak fluent Yiddish Altie?

Altie Karper:

Not on that level. With a dictionary, I can make my way through Yiddish literature if I sat with a dictionary, but I don’t have that fluency. So that’s what I would go back to graduate school and get my PhD in before I could then embark on this project.

David Bashevkin:

Absolutely interesting, fascinating. And any of our listeners, if you do in fact want to send Altie a manuscript, make sure it’s attached the money that would also allow her to take that sabbatical. My final question Altie, and I really cannot thank you enough for your time today. I’m always interested in the sleep patterns of the people I speak with. What time do you go to sleep at night? And what time do you wake up in the morning?

Altie Karper:

I go to bed about 11:30 and I get up at 5:00 and I am in a constant state of sleep deprivation.

David Bashevkin:

Altie, I cannot thank you enough. I hope that we get to see each other in-person quite soon, as we used to do in the past, but thank you so much for your insight, perspective, and wisdom today. My deepest appreciation.

Altie Karper:

Thank you. It was my pleasure. Hope to see you soon.

David Bashevkin:

I think what I take away from Altie’s story is her personal integrity and character in this story. How she even with opposition, even through a great deal of adversity, stuck to her guns, and did it with graciousness and gracefulness. But more importantly, it’s how even the community that she was affiliated with, even after it disappointed her, even after it proceeded in a way that she did not find sensible or did not find to be the right approach or the approach that she would have taken, she didn’t allow it to infect her with that type of cynicism, or she didn’t allow it to undermine her relationship with the community itself. Her connection, her affiliation, her pride remained intact. And that’s something that I’m not sure I’m capable of.

I think for so many when we look out and we sometimes see things that our community does or any community that we affiliate with does, there was that ah, I would have done that differently. I wish that didn’t happen. Or there’s that sense of embarrassment. I think there’s a normalcy to that, but where the real heroics take place is where you’re able to remain loyal, where you’re able to remain faithful, even when communities or individuals act in ways that you don’t necessarily approve of. It’s that type of flexibility and breadth that I think is needed for anyone to affiliate with any community. Not just a religious community, and it’s not just a Jewish question. It’s a question of, when you affiliate with a broad community, you need to develop the capacity to withstand that communal affiliation, even in the face of individual reservation.

So thank you so much for listening to this episode. It wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of shnorring. So if you enjoyed this episode or any episode, please subscribe, rate, review. Tell your friends about it. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. If you’d like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered, be sure to check out 18Forty.org. That’s the number 1-8, followed by the word “forty”, F-O-R-T-Y.org. You’ll also find videos, articles, and recommended readings. Thank you so much for listening, and stay curious my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Elissa Felder & Sonia Hoffman: How the Jewish Burial Society Cares for the Dead

Elissa Felder and Sonia Hoffman serve on a chevra kadisha and teach us about confronting death.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Red Flags: A Conversation with Shalom Task Force Featuring Esther Williams and Shana Frydman

We have a deeply moving conversation on the topic of red flags in relationships.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Shlomo Brody & Beth Popp: Demystifying Death and the End of Life

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shlomo Brody and Dr. Beth Popp.

podcast

‘Everything About Her Was Worth It’: The Life of Yakira Leeba Schwartz A”H

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yisroel Besser, who authored many rabbinic biographies and brought David Bashevkin to Mishpacha magazine, about sharing Jewish stories.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Rabbi Meir Triebitz: How Should We Approach the Science of the Torah?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

podcast

Anita Shapira: ‘You cannot wipe out Hamas’

Leading Israel historian Anita Shapira answers 18 questions on Israel, including destroying Hamas, the crisis up North, and Israel’s future.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Frieda Vizel: How the World Misunderstands Hasidic Jewry

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Frieda Vizel—a formerly Satmar Jew who makes educational content about Hasidic life—about her work presenting Hasidic Williamsburg to the outside world, and vice-versa.

podcast

Gadi Taub: ‘We should annex the north third of the Gaza Strip’

Gadi answers 18 questions on Israel, including judicial reform, Gaza’s future, and the Palestinian Authority.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Mikhael Manekin: ‘This is a land of two peoples, and I don’t view that as a problem’

Wishing Arabs would disappear from Israel, Mikhael Manekin says, is a dangerous fantasy.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

Recommended Articles

Essays

This Week in Jewish History: The Nine Days and the Ninth of Av

Tisha B’Av, explains Maimonides, is a reminder that our collective fate rests on our choices.

Essays

I Like to Learn Talmud the Way I Learn Shakespeare

If Shakespeare’s words could move me, why didn’t Abaye’s?

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Fighting for My Father’s Life Was a Victory in its Own Way

After losing my father to Stage IV pancreatic cancer, I choose to hold onto the memories of his life.

Essays

Books 18Forty Recommends You Read About Loss

They cover maternal grief, surreal mourning, preserving faith, and more.

Essays

Benny Morris Has Thoughts on Israel, the War, and Our Future

We interviewed this leading Israeli historian on the critical questions on Israel today—and he had what to say.

Essays

Why Reading Is Not Enough for Judaism

In my journey to embrace my Judaism, I realized that we need the mimetic Jewish tradition, too.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

‘The Crisis of Experience’: What Singlehood Means in a Married Community

I spent months interviewing single, Jewish adults. The way we think about—and treat—singlehood in the Jewish community needs to change. Here’s how.

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Do You Need a Rabbi, or a Therapist?