Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

Summary

This series is sponsored by our friend, Danny Turkel.

This episode is sponsored by Camp Morasha in appreciation for Rabbi Rothwachs’s tireless dedication to his family and ours.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

Larry is the rabbi of a congregation in Teaneck, New Jersey, and sees himself as someone who is sort of in the business of helping people. His daughter Tzipora was diagnosed with an eating disorder as a pre-teen. As Tzipora’s disorder got more severe, she was distanced from her family—both physically and emotionally. During this time, she and her parents were forced to redefine and strengthen their relationship in ways they couldn’t have otherwise.

- How can absence become a relationship in and of itself?

- What did this journey teach Tzipora about being a daughter, about family, about her relationship with her father, and for Larry as a parent, how did this change his relationship, not just to Tzipora, but his relationship to being a parent in general?

- How can parents and children remain connected even when so far apart?

Tune in to hear a conversation about how distance can make a relationship grow stronger than it ever was before.

Interview begins at 11:43.

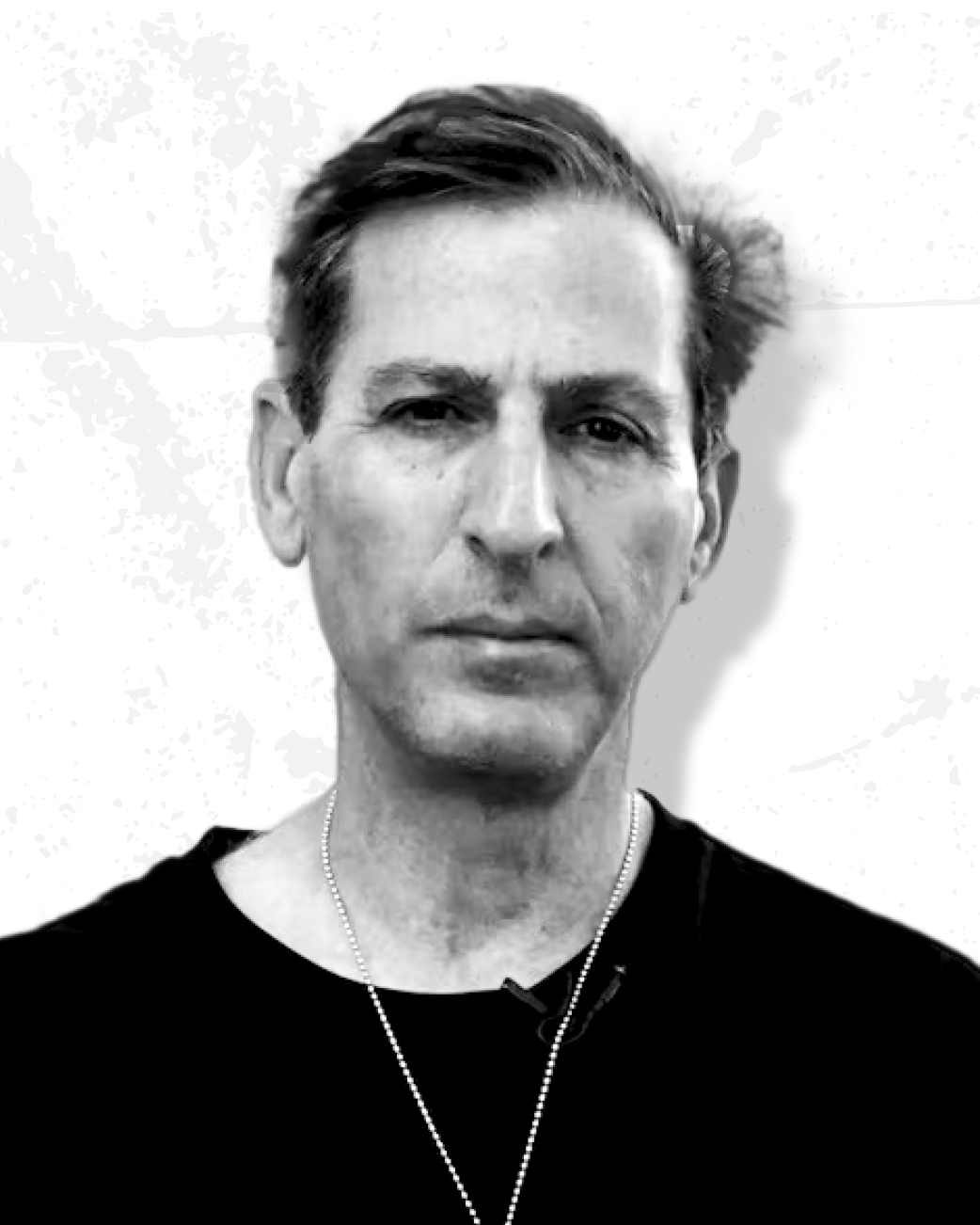

Rabbi Larry Rothwachs (father) serves as rabbi of Congregation Beth Aaron in Teaneck, NJ, and is the Director of Professional Rabbinics at RIETS at Yeshiva University. Rabbi Rothwachs has served as president of the Rabbinical Council of Bergen County and on the executive committee of the Rabbinical Council of America. In May 2016, he was named by the Jewish Forward among ‘America’s Most Inspiring Rabbis.’

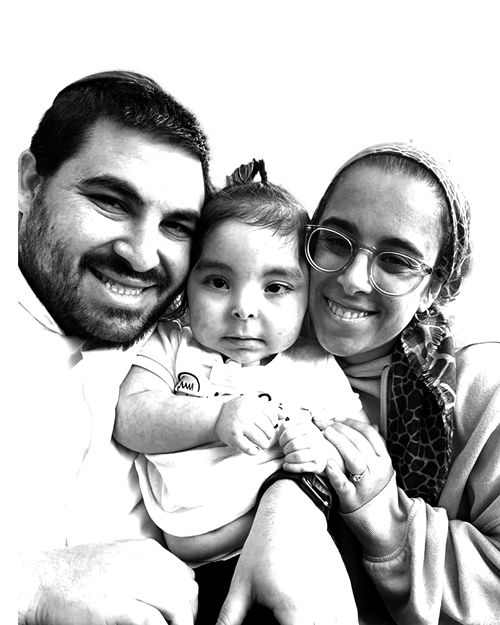

Tzipora Rothwachs (daughter) grew up in Teaneck, NJ, and studied Business at Yeshiva University. After graduating from Yeshiva University, Tzipora Rothwachs began working as a property associate for JLL in New York City. She enjoys running and the outdoors and lives in Bergen County, NJ.

References:

The Fifth Son by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson

Top Five Pictures of the Four Sons by Dovid Bashevkin

The Animated Haggadah by Rony Oren

Here Without You by Three Doors Down

Far From the Tree by Andrew Solomon

Transcript

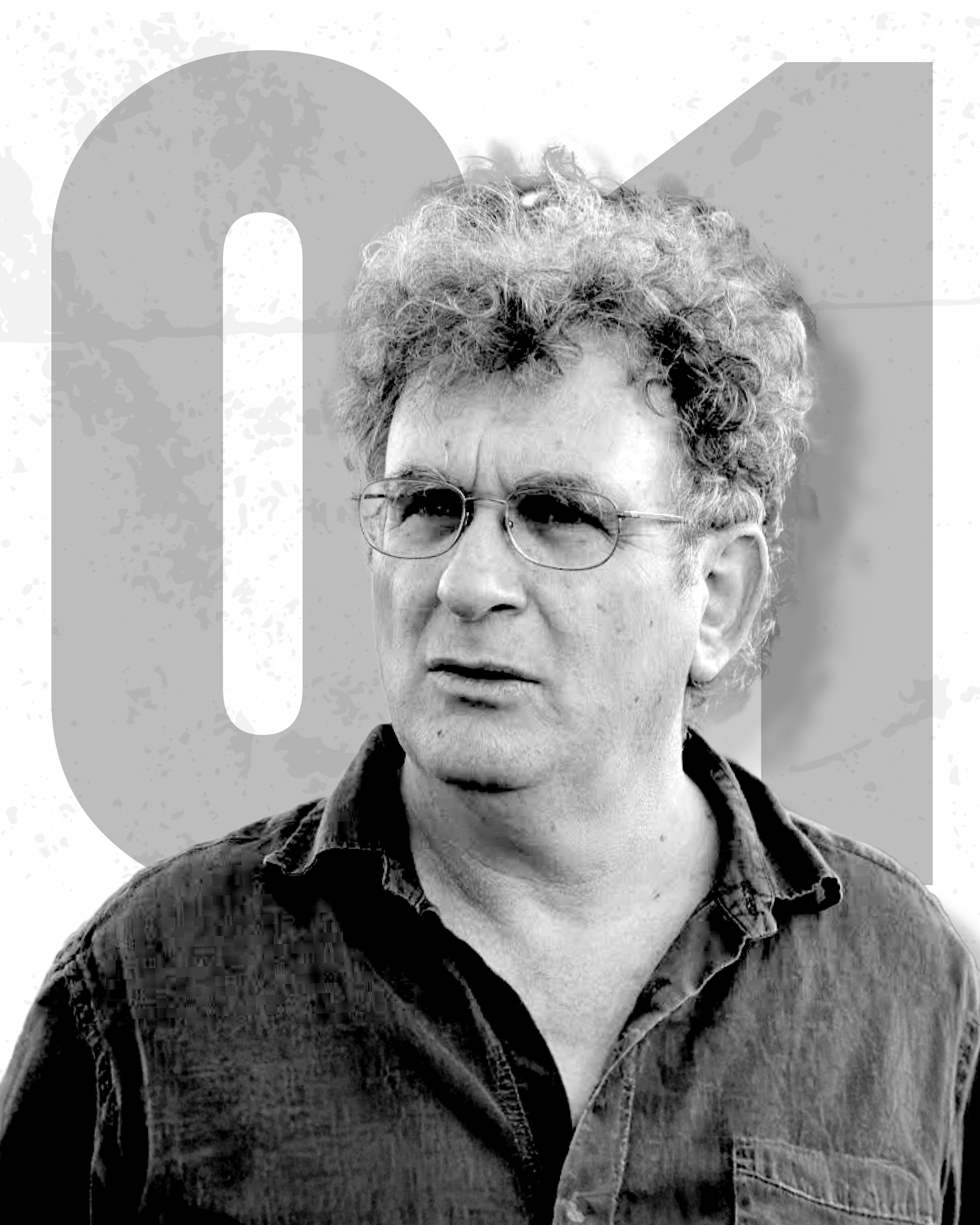

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month, we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin. And this month, once again, we’re exploring intergenerational divergence. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org, that’s 18 F-O-R-T-Y.org, where you can also find videos, articles, weekly emails, and recommended readings. Thank you so much for our episode sponsor, Camp Morasha and my dear friend, Jeremy Joseph, director of Camp Morasha for sponsoring today’s episode in honor of the camp rabbi of Morasha, Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his entire family. And thank you again to our dear friend, Danny Turkel for sponsoring this entire series.

There is a very moving letter that I heard quoted many, many times, but I never kind of read it inside until maybe a year or two ago. That was written on April 12, 1957, which was the 11th of Nissan of the year 5717. It was written by the Lubavitcher Rebbe. If you’ll allow me, I’d like to read the original Hebrew from the letter of the Rebbe and then translate as well just because I think the Rebbe’s language in the original Hebrew is all that beautiful. The Rebbe, Rav Menachem Mendel Schneerson of Lubavitch is known as the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe of Chabad. I usually just call him Rebbe. He writes as follows El acheinu Bnei Yisrael to my brethren, the Jewish people, v’askanei hachinuch b’prat b’chol atar v’atar HaShem aleyhem yichyu shalom u’bracha, to all of those involved in educational practices wherever you may be, greetings and blessings. Chag HaPesach, the holiday of Passover matchil begins k’sheyishal bincha when your child will ask, v’hegadtia l’bincha writes the Rebbe. V’yesh kama v’kama ofanim, there are so many ways b’sheila ub’teshuva, there are so many ways of asking questions and formulating answers b’hetem l’arba sugei banim, to the four types of children Chacham, rasha, tam, v’sheino yodea lishol.

This is the part of the Seder that’s known as the four sons, the four children. These are archetypes for the different types of children around the table. We always have the wise son, the wicked son, the simple son, and the child who doesn’t even know how to ask. And any Haggadah printed from the last several centuries always has curious ways in which they depict the different types of children. I actually wrote a Top Five one time for Mishpacha Magazine about my favorite depictions of these four types of children. I think my favorite is always the way they depict the wicked son. There’s one Haggadah where he’s wearing like a green suit and a purple tie. Looks like a used car salesman. I’m not sure why that’s the archetype of evil in this Haggadah.

Another one of my favorites is the Claymation Haggadah. That was the one that I used to use growing up where all the characters were made out of clay. I think the wicked son has a safety pin that he is using as an earring, which to me, is like, it’s pretty hardcore. It’s a pretty hardcore earring and I like that they preempted some of that hard rock ethic of having the wicked son wearing a safety pin earring. But the Rebbe continues, L’tzad hashoni shel arba banim, while these all differ, veheyotam hafachim zeh m’zeh, they’re opposites and different in each and their own way, yesh lahem tzad hashaveh, there is one particular way where all of these children are the same, shutfut, a partnership. “What is that way? ” writes the Rebbe. Afilu harasha, even the wicked child, sharui gam b’avodat haseder he too is present for the night of the Seder. Hu nifgash v’chai b’yachad im ovdei haavoda, he is living and present with the others who are involved in this service.

Im chayei Torah u’Mitzvos he’s present and integrated with those performing mitzvahs, v’hu mitanyen bahem, and I think he’s involved with them. He’s interacting with them. Davar zeh noten tikvah, there is a optimism, a tikvah, a hopefulness in the fact that he’s still there participating in the Seder even this wicked child. V’tikvah chazaka b’yoter, this strong optimism, shelo rak hatam v’sheino yodea lishol, it’s not just the simple child or the child who can’t ask. Ela gam ken harasha, it is even the wicked child. Yehiyu chachamim baalei deah shleima, shomrei Torah u’Mitzvos, They’re all there together ultimately, that while one is very wise and one is wicked and one can’t ask and one is very simple, ultimately, they’re all there together. Aval l’tzaareinu to our collective pain, bemeyuchad b’zmaneinu specifically nowadays, k’shehachoshech kaful u’mechupal, when the darkness has doubled over, when the difficulty and absence of the modern world that we live in is almost a double blindness. We don’t even know what we’re missing. What is absent.

Yesh od sug shel banim there’s another type of child, Haben sheino nimtza klal b’seder, the child who is not at the Seder at all. Hu eino shoel kushiyot, that child doesn’t ask any questions. Kevian shein lo shaychus bichlal, that child has no connection whatsoever im HaTorah v’HaMitzvos, to the tradition of Torah and Mitzvos, im dinim u’minhagim yehudiim amitiim, to that traditional Jewish life that the other children, no matter the wicked one, the wise one, the one who can’t ask, the one who’s quite simple, they’re ultimately all there at the Seder. But very often in families, there’s someone who is not participating at all. We focus a lot on the four children, but what sometimes obscures our vision are the children who are not participating at all.

Learning how to form a relationship with a child who is not present, who is not there is at the heart of the conversation that we are having today, a conversation that was not easy, a conversation that required a great deal of courage and vulnerability to even share. It’s a conversation between a father and child, Rabbi Larry Rothwachs, a dear friend, and his daughter, Tzipora, or Po as I called her throughout, and how during Tzipora’s struggle with an eating disorder, when she was not able to be present in the home at the table, how as a family, they were able to still continue, reach out, and maintain that connection and that relationship even in her absence. It’s a story in many ways that I think a lot of us may think of in the deep recesses in our mind when we gather around a Pesach Seder, there are relationships that are not able to be fully present, fully embodied around that table.

Maybe it’s with people who are actually physically there, but emotionally, they’re alienated. They are gone. They’re no longer participating, or maybe it’s people who didn’t want to show up at all. But the notion of learning how to forge a relationship even through periods of absence, the notion of learning how to reach out and not let go even when someone who’s in that relationship is running in the other direction, is struggling with something that doesn’t allow them to be present, is something quite powerful and something that I know a lot of families struggle with. I think part of the pain, like the Rebbe says in describing this, aval l’tzaareinu to our collective pain, u’bemeyuchad b’zmaneinu, specifically in our time, k’shehachoshech kaful u’mechupal, the darkness is doubled over. This notion of darkness being doubled over is the idea that sometimes the suffering that we have, it’s quite obvious and quite apparent and you know you’re going through it.

A darkness that’s doubled over is an absence that is so far gone that people don’t even know that something is missing. And I think when we look at a lot of other families and we look through windows, proverbial windows, and we look at other people’s lives, which is a natural part of growing up in any community and particularly the Jewish community, a lot of times, I think we struggle from this choshech kaful u’mechupal,the doubled over darkness. Where when we look at other families, we sometimes only pay attention to the absences that we can see, the apparent difficulties that they carry with them quite visibly and quite apparently. But I think every family has a doubled over darkness, a darkness that they’re not yet ready to share with the world, a darkness that nobody else knows about, a difficulty, a pain, a struggle, whether it’s with a family member, whether it’s with their own lives that the world has no idea about whatsoever.

And that people looking in who may be wistfully thinking, if only I had it like that family, if only I had it like that home, like that Seder, like that picturesque family ideal, yet they don’t know that there’s a doubled over darkness. There’s an absence that they can’t even see. There’s a struggle that they may not even be aware of that’s animating inside that home that nobody else has any idea about. I think in many ways, this is a story of somebody, a family, a father and a child, who even in that doubled over darkness where not everybody knew what they were going through and been with the absence of a child, a father was able to reach out and remain connected.

A family was able to remain deeply connected to a daughter, which I think in many ways when you listen to this interview, you see the capacity of a family to include so much, to include so much pain, to include so much struggle and be able to have a frame that even with the difficulty and with the tough conversations and through the absence, you’re still able to frame it and have the capacity for deep love. I think for all of us, when we look at our Seder, we should think in many ways about maybe who might not be there. Maybe they’re a person, an individual who, whether or not they’re expected to be at our Seder, maybe they’re missing from a different Seder, maybe it’s somebody who’s not fully present at our own Seder, but developing the capacity to create a presence of relationship even through absence to be able to allow and create space for people in our lives to be fully embodied, fully present, fully participating requires us first to notice and appreciate their absence.

And I think this story of a family negotiating with absence, negotiating with alienation, negotiating with tremendous difficulty gave me a great deal of inspiration to notice who is collectively still engaged in a part of our collective religious lives and who may be missing, who may be outside on the door gently knocking, trying to find a way in, and learning how to develop the capacity to ensure that all of our families and by families, I don’t mean our immediate families, I don’t mean our cousins, I don’t mean the people on your program, I mean the larger family of Knesses Yisroel to find a place where everybody can have a seat at the table to be fully present where we no longer have to lament not just the wise, the wicked, the simple, and those who can’t ask, but we no longer need to lament the children, the individual, the experiences that aren’t even showing up at all.

I think this story of this particular family, this courageous story, this heroic story gives us a frame to appreciate how to create room in our lives and our collective Seder for everyone to be present. It is my absolute privilege to introduce our conversation with Rabbi Larry Rothwachs, and his daughter, Tzipora. I want to introduce our guest today, and I’m so excited to hear their story, to discuss their experiences. That is my dear friends, Rabbi Larry Rothwachs who lives right here in my neighborhood in Teaneck and his daughter, Tzipora Rothwachs, or do you prefer Po?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Either works.

David Bashevkin:

I’m a big fan of the nickname Po. It’s like one of my favorites. I have a Po who’s a niece. We’re talking today about your journey. You struggled with an eating disorder, which obviously can disrupt your individual life. It really can take a toll on a family life. I’m wondering if you could begin with some context about what was your family life before this happened? You do grow up in a rabbinic home, but what was happening before an eating disorder emerged?

Larry Rothwachs:

Okay. I guess I’ll begin. Thank you, Rabbi David for this opportunity. Really, is a great personal privilege and an honor. As I mentioned to you before we got started this morning, it’s really hard, I think for the both of us, to believe that this is how happening because this really is a story that I think many people know, but very few people actually know. It’s the story that we ourselves are still in the process of discovering and completely coming to terms with on so many levels. Our life before Tzipora developed an eating disorder was, I guess from a certain perspective, unremarkable. As you know, we have somewhat of a complicated life being a rabbi and living in a fishbowl, as people like to say. There’s nothing typical per se, about a rabbinic household, but my wife and I always try to prioritize our family and we, I think we succeeded in achieving balance both in general and addressing the particular needs of our individual children.

I think we had, and still maintain Baruch HaShem, a good relationship with each and every one of our children. I think that what happened about 12 years ago, a story that we’ll share bits and pieces with you today, was such a major disruption and actually set our lives on such a completely different course. In some ways, it’s actually difficult to sort of remember what life was like beforehand, because on a certain level, it’s changed so much dramatically since.

David Bashevkin:

I was wondering. Let’s fast forward to, I like calling this term a nexus event, when you realize that things are different than the trajectory, than the story that most people have in their heads, which is you grow up on this moving escalator that takes you from childhood to adulthood. You don’t really have to do anything. Then all of a sudden, you realize something different is going on there. There’s a struggle here. When did you first realize, and on that you, I’m asking both Po and your father, when did you first realize that this trajectory was not going to unfold as sequentially and naturally as you had originally expected, as everyone naturally expects their lives to unfold?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Okay. For me, I was a happy child. I had great siblings. It was definitely a challenge being a rabbi’s daughter and setting an example and feeling that everyone was looking at you in a certain way and you had to, in a way, like-

David Bashevkin:

Behave. You had to live up to a certain standard, I’m sure.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah. For me, I was 11 years old. I remember going to Israel that summer and my mom at the time was working on Michlelet and I was with my whole family in Israel. It was great. My bat mitzvah was coming after the summer and I wanted to lose some weight for it, so I started dieting and getting into exercise. There was a gym in Michlelet. I remember going with all these Michlelet girls while I was 11 years old and thinking I was cool for that. Then I would say I started restricting and became very picky with foods. My main focus a bit after that was just losing weight and it became my only focus. I came back from Israel and I remember going to a doctor. At the time, I actually spoke with my dad about this a few weeks, days ago. I don’t know.

He told me that at the beginning, she said, “She’s fine. This is normal,” whatever, but I do remember going to Israel and then coming back and going to a doctor who told me that you have anorexia. For me, I feel I took that as okay. Like, okay. I didn’t really A, process it or B, care. I was so in the moment and so into losing weight and doing my thing that I didn’t care what anyone had to say. I really didn’t. That’s skipping ahead, but I’ll just bring it in. When I went to therapist or nutritionist, I would usually walk in with my middle finger up.

David Bashevkin:

Straight up.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Straight up. Straight up. Middle finger up. I would-

David Bashevkin:

Lost girl attitude.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yes.

Larry Rothwachs:

Sometimes it was even both of them, if I remember correctly.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah. I’m stubborn. I was very into what I was into. And I was lost and I didn’t want the help to help me get out of it. From there, I just got deeper and deeper into it. Do I continue here?

David Bashevkin:

We could stop for a moment. I’m really intrigued that you were so young and you were able to even have the stamina to stick with something when therapists and your parents, I’m sure, were getting nervous and concerned. It takes a certain almost confidence to be able to go through with something like that when other people seem to be getting concerned. Where do you think that was coming from that even, I’m sure you had early conversations with a parent worried about you? Your reaction was what when they initially came to you and said, “We’re worried”?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I guess in the beginning, yeah, I didn’t really take it as anything, like I said, but I definitely remember one birthday going with a few of my friends, middle school, to this frozen yogurt place with my mom. I remember what I was wearing that day and I remember going and them looking at me in a weird way, like all of them. It could have been in my head, but I remember them looking at me in a weird way. I actually remember one of my old friends, her dad. I remember him always staring at me. This was not in my head, but no, I remember being looked at differently and almost as if people were looking at me like they were concerned for me. Obviously they were, but at the time, it was an uncomfortable feeling. Everyone just looks concerned. I remember my mom looking at me like she was… I don’t even know how to explain what the face was, but it was kind of like she looks sick. She looked at me like she was the sick one or something. I don’t know.

Larry Rothwachs:

I think in retrospect, things unfolded very typically. This is the way eating disorders often evolve over the course of time. Unfortunately, we were not prepared as a family to really deal with it. While maybe there was an element of denial, I think we were just not addressing some of the signs as early as we should have. And then, as Tzipora sort of indicated in her own self-description, it really builds a lot of momentum over a pretty short period of time. Eating disorders, they operate a bit like a vice. If you pull at them gently, they pull back with much more aggression and it becomes this fierce battle. I’ll just say one other thing that I actually do remember in the early days, you feeling a tremendous amount of confidence, feeling almost like a rise.

I think in some ways, getting all of that attention, even though it was concern and worry from people who loved you, and I’m sure there was a part of you that felt bad, at the same time, being able to demonstrate such self-control to be able to restrict day after day after day, and look at everybody around you not be able to control what they eat and how much they eat, just being able to look at them almost with that look that you’re giving me right now is something which may give a person a sense of control, ironically, even when you’ve lost that control. I don’t know. To a certain extent, as a parent, as we’re watching this happen, you feel like, “Wow, my daughter, she’s looking really happy. She’s looking really confident. She’s looking very, very secure.” So two things are happening at the same time. She’s coming apart at the seams, at the same time, feeling good and emotionally driven. At a certain point, everything collapses.

David Bashevkin:

Can we talk about, the gentle, I’ll use that analogy, the gentle pull has an aggressive pull back. As a parent, for you, what was the initial pull? I mean, you see your kid. They’re not eating healthy. They’re losing weight. For you, were you immediately like, we need to go to doctors. We need to figure this out. What was the initial pull and then what was the more aggressive pushback?

Larry Rothwachs:

Right. I think the reason why parents often, in situations like this, pull gently is for two reasons. Number one, you love your child. The last thing any parent wants to do is to inflict any additional pain and suffering upon their child. So if I see that my child is weak and tired and losing weight, I know that there’s a part of them that is already suffering. So to go ahead and to add more to that, to make them feel bad about that, ashamed, to make them feel like somehow they’re failing themselves or others, it’s not intuitive. It really actually runs, in some ways, counter to what we want to do as parents. As loving caregivers, we want you to be happy and comfortable. So that’s number one. The other reason why I think in general people pull gently is because to pull aggressively at an eating disorder, to challenge it sometimes requires major sacrifices for some or all members of the family.

It requires a level of care that sometimes, there’re just major disruptions involved in terms of scheduling and traveling. There are major costs involved. And as always, you want to take the path of least resistance and you can’t believe that something like this is really going to take what’s required. Had we known when this all started that this was going to be not a three or four-week journey, but a three or a four or maybe even a five-year journey, there’s no question in my mind that we would’ve acted much sooner and much more aggressively if we could have.

David Bashevkin:

So maybe tell me, when did you realize that this is going to require a more serious intervention and what were the more serious interventions, for listeners? Again, this isn’t a series on diagnoses or understanding eating disorders in particular. This is a story of a family and how to navigate family issues, but maybe you can give a little bit of background and understanding to just what’s that big moment where you realize that-

this is more than a three, four week… This is more than a phase, so to speak.

Larry Rothwachs:

I think what was happening over the course of several weeks and months, was we were looking for anything that would be a sign of hope. We would grab onto anything, which looked like things were turning around and moving in the right direction. Again, in retrospect, and maybe even at the time we realized, it was actually one step forward, 10 steps back. Day, after day, after day. And you begin to speak to more people and you do your homework and people start mentioning things like residential treatment, inpatient treatment, hospitalization. Doctors are taking vital signs and realizing suddenly my otherwise perfect healthy 11, 12-year-old daughter has low blood pressure, her heart rate is low.

There’s a certain point where you just sort of can’t deny the severity of what you’re facing over here. This is not a simple thing. This is potentially life threatening. I do think that for us as a family, and particularly for Tzipora and I, as two people, it sort of came to a certain point where, it was sort of a point beyond return.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I don’t think that’s what made me feel like I have an eating disorder. That’s just what made me hate you.

Larry Rothwachs:

Okay. At the moment. No problem, so tell me, what would you like to say here?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I guess I already said that piece though. That’s when everyone was looking at me differently, that’s when I thought there might be an issue.

David Bashevkin:

Well, you just mentioned something. You said there was a point where something happened that made you hate your father. That’s a powerful feeling for A, a father to see and for a daughter to feel, what made you hate your dad?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I never hated him, but-

David Bashevkin:

He’s too lovable.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah, no, I never hated him. In the time, I was very angry at him and no, I was very angry at the situation. He called the ambulance in front of my siblings and I was just embarrassed in general. Also scared, like what? I’m not getting in an ambulance, like that’s extra. I always thought all these things were just extra. I don’t need an ambulance. I’m not dying. I just really didn’t think anything was wrong. I don’t remember at that point thinking that there was any real issue, but my dad called the ambulance to get me to a hospital. And that was very embarrassing for me. And it was scary. After that, I moved into my grandparents house for about a month and I did not talk to my dad for a month. I remember pulling out of the driveway and looking out the window and seeing him stare down at the car that was driving away. I remember it in slow motion.

David Bashevkin:

As like standing alone?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

No, it wasn’t like that. It was sad. It was like, I didn’t want to go. I didn’t want to go but a big thing for me was I pushed everyone away that was trying to help or trying to be there for me. Because at the time I didn’t want anyone to be there for me. It’s not that I didn’t want them to be there for me. I wasn’t ready to accept any sort of help. I wasn’t ready to … I didn’t understand the whole eating disorder, anorexia piece myself. To understand how to overcome it or how to get the help I need or yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Let’s talk a little bit about your relationship because that’s really what this is about. When you, she moves into her grandparents’ house. I assume that’s your in-laws?

Larry Rothwachs:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

You move into your grandparents’ house, as a parent, what do you do now? I mean, she’s not living under your roof anymore. You want to let your daughter know why this is necessary, but also that you still love her. How does that change your relationship at that point?

Larry Rothwachs:

There were many moments sort of iconic moments during this multi-year period. That I think I was just feeling an extraordinary amount of pain. Sort of feeling like you’re staring into the abyss. I wouldn’t say that this moment was necessarily the worst, but it was certainly the first. I think in that respect, it was. I was feeling my daughter sort of slip beneath my fingers. There was nothing that I was able to do until this point to rescue her. The only thing that we really had until that point was an open line of communication. She may have not been accepting our overtures for help. She may have not been expressing her appreciation and she certainly was not complying. But at the end of the day, we were still father and daughter. We were still a family. There were moments that we would hug each other. I think that kept both of us going. At this moment, that Tzipora mentioned, and it came after multiple threats, where I did, I think what was unthinkable for both of us. In retrospect, it was Kleinekeit, but I called 911. She looked at me and she said, “We’re done.”

She was 12 years old at the time. She said, “I’m not talking to you.” And she left the house this she just described. My heart was absolutely shattered. I thought that I’d be hearing from her later that day, but a day turned into two days, which turned into a week, which turned into two weeks and three weeks. She was in constant contact with my wife and other members of the family, but she completely shut me out. And that was a very, very painful thing to experience as a parent. Particularly someone such as myself who is sort of in the business of helping people. I’m in the business of trying at least to rescue people when there is no one else. Here, my own flesh and blood completely shut me out. So that was painful. It took time for me to realize that actually, that was a moment in which our relationship was probably at least on a foundational level, becoming stronger than it ever was before.

David Bashevkin:

Why is that?

Larry Rothwachs:

Because relationships are forged in moments of great pain. People were telling this to me at the time, I couldn’t really understand it and I certainly couldn’t feel it. Tzipora felt extremely secure with the decision and I made too call 911. She was so frightened by it. She felt so threatened by it and she was angry by it. She was smart enough at the time to realize that there was tremendous amount of sort of self-sacrifice that was involved in all of this. I think in ways that she couldn’t appreciate and express at the time, she genuinely appreciated that. When there was a moment of reunion, which was somewhat dramatic, it wasn’t that we just picked up where we left off. It was actually, it was an embrace, like never before.

David Bashevkin:

I want to come back because you described it a moment of anger and difficulty. I want to ask Tzipora question because you didn’t use any … That wasn’t the main word that you used. You used the word embarrassing. I’m curious if you could reach back, what’s the embarrassment, meaning your family knows what’s going on. People know what’s going on, so in your mind, were you embarrassed about?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I was embarrassed for my sisters, my brother, people on the street, to watch me get in an ambulance. I find that to be very embarrassing. I found that to be very embarrassing at the time. Not only that, yes, I was very scared of the whole, I don’t like that. I’m scared of hospitals. I’m scared of that stuff. When I see an ambulance, you picture either an elderly person to be in there or someone that is, I don’t know. I just, I didn’t think I was in need of an ambulance. I thought it was very extra and yeah, it was embarrassing. I remember seeing my siblings on the top of the steps. On the top of the steps and-

David Bashevkin:

That’s a hard feeling. No, that’s what hit me the most when you kind of like to admit, with all the fear, scared, but that sense of embarrassment to feel like you’re bringing attention to yourself or announcing that something different is going on. That’s really, really painful. To admit that and to talk about that is quite powerful. I’m wondering, you were talking about these steps and what I really want you to reflect on, before we get to some of the sweeter moments, is what were mistakes that you made during this period? Meaning you look back now and whenever you’re reflecting in retrospect, it’s never going to be perfect. No one’s doing the right thing and it’s the first time you’re handling it. Are there specific moments that you look back at and say, “I should have done something differently then?”

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah, definitely. I actually, in terms of family and shutting my dad down for a month, I remember that month being very painful for me. I felt very alone and my dad, he’s always been the person I would go to if I needed something, not-

Larry Rothwachs:

Not everything.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

He’s always been the person I would go to for like the smallest things. He would always make me feel better about it. Friday night. I would worry about getting older when I was five.

David Bashevkin:

That’s so interesting. I had that fear too. Meaning just like imagining yourself as an adult.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Can I share something like really random?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Go for it.

David Bashevkin:

There’s this movie called Father of the Bride, just with Steve Martin. It’s like a comedy. It’s like the sweetest movie. At the end of the movie, the father plays a game of basketball with his daughter. You see in the movie that the daughter, there’s like an image of them when she’s like a little kid and then like she rapidly grows up. I saw that movie, I wasn’t five, but I was probably like eight. And I started crying like uncontrollably. It hit me emotionally so much because you confront just the river of time rushing forward and feeling that your own childhood is not permanent. That sense of being cared for is not permanent. I remember my parents, it’s like the sweetest comedy.

Literally our family, getting arrested in the store because they sell eight hot dogs, but only six hot dog buns is something my father would absolutely do. We would always talk about that. That whole movies about my family and they were making a wedding at the time, with my big sister. I remember that final scene of playing basketball together. I don’t know if you ever saw it. Did you ever see Father the Bride?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I definitely did.

David Bashevkin:

It’s really a classic, but that fear of getting older quickly and losing your childhood. I don’t know if you had that. If that’s the same feeling you’re describing, but it’s something that I absolutely dealt with.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yes. That is what I’m talking about. I’ll tell you, to go back to what my dad was saying, about how that month of us not talking, brought him closer. I feel the same way. After I didn’t talk to him for a month. I remember my mom coming to my grandmother’s house and saying, “You need to talk to Abba. He’s going to have a heart attack. He’s not well, you need to talk to him.” And I remember sitting on her lap while she was telling me that. At that point I needed to talk to him too. It was just it. I always wanted to talk to him. It’s not like I was like ignoring him on purpose or like I wanted to, I just, I didn’t want to give in, in a way. I really was felt what did was so wrong at the time. I was trying to maybe prove a point in a way. I don’t know what I was doing, but I do remember not being good that month. I felt lost. I felt lost throughout this whole process, but I felt very lost without my dad in my life.

David Bashevkin:

It’s interesting. You were kind of like, and I may be totally off base in even suggesting this, but you were kind of like the same way you restrict yourself from food. That ends up being the relationship and obsess with food itself. You’re almost restricting yourself from your dad. From that very relationship. That itself, that absence was a relationship in and of itself.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

I want to give you time to kind of weigh in and reflect on this. When you think back, what do you look back at mistakes that you made during this journey?

Larry Rothwachs:

Oh, my wife and I are very forgiving of ourselves in terms of the things that we didn’t do, when we should have done them. At the end of the day, we were doing the best we could. We were working with the script we had. It’s not just hindsight is 2020, we’ve become much more informed and experienced when it comes to eating disorders in general. So yeah, it’s clear to me right now that there were things that we should have done earlier, more aggressively. As Tzipora related earlier, as strange as the sound, we actually should have ignored the advice, which was well intentioned from a pediatrician. Who basically told us, when all the warning signs were there, this will go away, just ignore it. I don’t hold myself accountable for that. Actually I do feel that things needed to play out the way they did in order for us to ultimately find the way to the clearing.

Although, several things that I actually do think that I would do differently and I do look back on with a certain degree of regret. First is, there were times that I said things that I didn’t mean. When you’re standing on the brink and when you are staring at the malach hamaves in your face, every day. It’s just sort of this battle for life. It brings out some ways the best in some ways, the worst of you. There were things that I said to my daughter, about my daughter, that I didn’t mean, but you sort of can’t help it. There were moments that there was so much-

Tzipora Rothwachs:

What did you say about me?

Larry Rothwachs:

Well, you were always there. I didn’t say anything about you when you weren’t there.

David Bashevkin:

I’m curious too. Thanks for jumping in there. Because I was like, what exactly did he say?

Larry Rothwachs:

You just can’t believe what’s happening. Part of the challenge, whenever you’re dealing with trying to help and provide care and comfort, to someone with a behavioral illness, it’s very different than dealing with any other physiological illness. Where there are symptoms which are so clearly beyond their control, you would never say to somebody with a broken leg, “Stop being such a baby, just walk,” normally. You would never say to somebody with cancer, “What’s your problem? Just get over it.” But when you are looking at somebody who looks otherwise normal and healthy who refuses to eat, and is slowly but surely dying, you know, you can’t help, but look at that person and say, “What are you doing?” Unfortunately, like I said, sometimes the words that are used and the way that it’s expressed is much less refined, much more colorful. We’re human beings and it is what it is.

I will say that on the flip side, I think that I came to develop within myself, a much greater degree of self control in general. Particularly, when it comes to understanding and appreciating, sometimes the best thing to say is nothing. I had to fail at that again and again and again and again. I look back, some of the moments, like I said in the fight for life were not my finest moments. Another thing, and this is a little bit of a deeper point and I’m not quite sure that I would say that this is a regret. Knowing what I know now, I wouldn’t do this again. I was trying very, very hard to rescue Tzipora. That was sort of my role in all of this. I was the rescuer. I mean, you could read about that and learn about it. It was a role that I didn’t realize, but I guess I had sort of auditioned before in advance.

David Bashevkin:

That’s like a term.

Larry Rothwachs:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

The rescuer.

Larry Rothwachs:

I was like, I was going to fix this.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Larry Rothwachs:

This was my place. And it was incredibly, incredibly frustrating to not be able to do that. I didn’t realize initially, how I’d become so consumed with saving her, that I had slowly become somewhat neglectful or maybe to a large extent neglectful of other people in my life. At no point, did it reach a crisis level, but it was very clear that I needed to sort of readjust. At a certain point, remind myself that I have a wife and children, I have a community and I have myself, all of whom need care and attention. I wasn’t succeeding. This was a journey that we were all on together, but there were things that Tzipora needed to do. There were things that needed to happen that I couldn’t do. I couldn’t facilitate and I could no longer impose my will, my expectations on her in that way. And so I would say that knowing what I know now, I wouldn’t try quite as hard.

David Bashevkin:

Interesting. That’s really, really interesting.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Can I add one thing?

David Bashevkin:

Of course.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

If I could go back a big mistake, regret that I have, is not only how I treated my parents, but other people around me. My therapists, my doctors, everyone trying to help. I remember walking into my first psychiatrist. Her name was Eileen Miller and yeah, two fingers up. And I really, really, really was mean to her. I said mean things to her and I stopped seeing her at one point and went to another doctor. I got the chance to work with her later on and got the chance to not only be her patient, but to be her friend, and to take her advice and to give her a hug. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Did you apologize? That’s such an interesting thing. You had one period where you’re seeing a certain psychiatrist doesn’t go well, and then there’s a second period where you come back to them. Did you like say … It’s a weird thing. I never imagined. I also, I was in therapy at a fairly young age and I could be obnoxious. Did you apologize to her? How did you break the ice that second time?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Eileen Miller actually died last summer. And I remember my dad calling me Saturday night and telling me that she died and it was a shock. She wasn’t sick or anything. At first, I don’t think I processed it. I remember for a week just really feeling down, couldn’t get it out of my head. I still think about Eileen a lot. She was a big part of my recovery and I wish I thanked her. I didn’t, but when she died, I sent her a text and made me feel better. It was a long text, but Eileen’s just an example. Because so many people, that I was just so rude to and mean to. The fingers up and just-

David Bashevkin:

There’s something so deeply beautiful about, even after she had passed, you just wanted to like write something to her. To like give that closure and appreciation for somebody who was able to get you through last leg of the journey. I know for myself, I get most emotional when I think about the people who really supported me and carried me through dark, dark times of my own life. It’s hard to talk about. It’s hard to reflect on, because it calls up a part of ourselves that it’s who we are. When you talk at it, you feel like you are touching on the most intimate parts of who you are as a person. Because they really pieced us back together. I’ve shared this before. It took a long time for me to get married.

I was dating for a very, very long time. I had a therapist who finally got me over the finish line. When I finally had a child, the first person I texted after my immediate family was my therapist. I wanted to let her know that … Have a moment where I could reflect back and say, “You were a part of this journey in the most real way.” It’s more than just like a doctor, a service person, but this journey, this accomplishment, this moment, you’re here, you’re here with me and you really made this happen. I’m wondering if we could shift. That notion of going back and thanking the people who stuck with you even when you were two fingers up, as you say. It’s a powerful thing to reflect on.

I think of people in my own life, who maybe I didn’t even go back to thank. It requires a great act of bravery. I want to shift and talk a little bit about the period where you were not living at home and developing relationship between father and daughter, when there’s the most absence. Meaning there was a period where you had to go to a residential treatment center, is that what we could call it? Is that what it’s called?

Larry Rothwachs:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

David Bashevkin:

I’m wondering if you could say, what were the events that finally allowed you to accept that level of help? Then, maybe we could talk about how you stayed connected? How you spoke with your family? Was it visits? Was it phone calls? Was it letters? How do you stay connected in that period? Maybe take us to the moment of your ability to like accept the help to take you to a place outside of your home.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

The first hospital I got admitted to was Princeton. I think this was a week after me and my dad made up. I remember I was sitting in a room room for like three hours writing things down. My mom was writing paper, like doctor, you have to fill out forms for your child.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. Yeah.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Originally they told me, “Yeah, we’re just going to go for a quick visit. Just to see some doctors.” They both knew they were leaving me there, but I guess they said that just so I would comply and go. Then, they said I was going to get admitted. Again, I’m just like, what does that even mean? Kind of same thought that when I first heard anorexia from that doctor. This time it really was freaking me out. What do you mean? I’m 12 years old, you’re going to leave me here type.

Yeah, they left me. I remember freaking out and being in a hospital room with a hospital bed and hospital sheets, being guarded by like, her name was MJ and Bethany. Other people were there. And my mom and dad like hugging each other as the door is closing. I really remember it, like it was yesterday, the door closing and it felt really scary and like alone, I was 12. Like I said before I got picked up from my sleepovers. I was alone in a hospital room. I didn’t have a phone. I didn’t have anything. I had an iPod, but they took that away. As soon as they knew I was texting my dad or something. It was scary. That was the first hospital I went to. Actually that was the one time I think I complied in a hospital. That first day at Princeton because I did everything. This was my first experience in a hospital. I’m just like, “I need to get out of here.” They told me what I had to do and then you can get out. My main focus was let’s just do it and get out of here. So I did it, I ate the food.

David Bashevkin:

In that period, when your parents are dropping you off in a hospital, what are you feeling towards your parents? What are you feeling towards your dad?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

At that point, I just wanted them. I wasn’t mad at them. I think I just wanted them. I wanted them. I wanted to go home with them. Obviously, I’m like, “How can you leave me here probably?” I don’t remember exactly, but I remember just wanting to be with them. I wanted to be next to them. I wanted to be sleeping in their house with them, but I remember being really scared and I didn’t want to be in Princeton. So I complied in that hospital. I got out of there. I think that was the only time I ever complied in a hospital. After that, I was home in and out of Princeton for a while. Went to Cornell, broke my dad’s glasses on the way in half.

David Bashevkin:

Why’d you break your with dad’s glasses? Frustration?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

His glasses are much nicer now, anyways.

Larry Rothwachs:

You see the first admission, you can get away with. We’re just going to speak to a couple of doctors.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Larry Rothwachs:

You can only get away with that once.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Larry Rothwachs:

In the years that followed, whether it was Cornell, Denver, Portland, different cities that we were visiting along our journey. Each admission was complicated. Literally, the trip, the journey there was complicated. It was complicated.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning in between, when you had to go back is that considered a relapse or first time, it was just like, I just want to comply to get home.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah. I don’t think it was ever a relapse for me. I don’t think I ever made it out. I think I was just sent home because-

Larry Rothwachs:

There’s only so long that-

Tzipora Rothwachs:

That they keep you there.

David Bashevkin:

Got you.

Larry Rothwachs:

Some of these places are going to keep you, until they realize that we really need to look at the big picture over here. Sometimes for certain kids, I suppose, a patch up here and there is all that’s necessary, in order to give them what they need to be able to maintain at home.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I think these hospitals, I think being sent to hospitals and treatment centers for me, tell me if I’m wrong, but I think it was just to get me to a normal weight so I

come home and do my thing again at home.

Larry Rothwachs:

Again, that wasn’t our goal, but it could be that’s the way you were looking at those periods of time. I got to do what I do so I can go back home and do what I like doing. That certainly wasn’t our goal.

David Bashevkin:

I’m wondering if you’re comfortable, I want to talk about a relationship during periods of absence, which, you know, I remember… This is nothing compared to what you’re going through, but it’s calling back a lot of my own memories as a child. When I was a kid, not often, but often I’d get very angry, particularly at my mother for certain things. The way that we would make up is I would always slam the door, lock the door, and my mom would go into her room and I would always like write her a note.

I would write letters and slip them underneath her door. I would always be somewhat surprised when my mom would slip it back under. I’m sure my mom knew that this relationship was going to heal in practice, but the exchanging of notes is what allowed me to a process a lot of my own pain because talking it out… I don’t know, there was something so immediate and so in your face when you talk it out with somebody that it’s hard to separate the emotions that you had and speak them out. Sometimes writing a note is just easier to say, “I’m sorry.” I know you were exchanging notes during that time or exchanging…

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Mainly my dad and my mom sending me notes, emails that they would print out for me and give. There were times where I couldn’t speak to my parents like even on the phone.

David Bashevkin:

You were not allowed because of the hospital.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Yeah. They would not allow me to speak to them. You had to get to a certain level or something. But I do remember they made exceptions for me because usually people get to the level to be able to speak to their parents, but as stubborn as I am, I wasn’t making it to that level. I think they made an exception to print out some emails. And these letters weren’t just a paragraph, they were pages of comfort. I don’t know, I slept with them. I still have them.

David Bashevkin:

You slept with them in your bed?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Not slept with… I read them before I went to sleep. I read them before I went to sleep. A part of me felt like he was there, my dad was there, my mom was there. And my dad’s a great writer, but there was something about the things he was saying to me.

David Bashevkin:

What did you feel when you read those letters that your parents sent to you? And what did you wish you could say to them that you were only now able to say or explain that you maybe didn’t have the ability to say to them back then?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

It’s hard to explain how someone with a severe eating disorder is thinking. Their brain is hijacked. It’s the only way I could think about it. To be honest, because my brain was so depleted from the eating disorder, I really don’t have day to day memories of how my relationship was with my parents. I was focused on my own misery. And in some ways, like, I was determined to keep my eating disorder alive. And once I was in a physically better place, I really never had a moment that I didn’t feel I needed my parents. My relationship with my dad had its moments, but he was always there. We were always connected in the same way. It was… Yeah. When we meet up after…

David Bashevkin:

That month

Tzipora Rothwachs:

… that month that we didn’t speak, he took me to a park, a memorial park in Fair Lawn, and he played a song, Here Without You by Three Doors Down. And ever since, it’s been our song. Every time he finished a letter, he would always go, “Here without you, always and forever, Abba.” It’s still our thing.

Larry Rothwachs:

It became our song, certainly during those years of separation.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

It’s still our song.

Larry Rothwachs:

It is.

David Bashevkin:

It’s deeply moving. I feel some measure of obligation to mention that I have seen Three Doors Down, I think at the Roseland Ballroom, probably in 2000. They became famous because of their song Superman. Are we thinking about the same band?

Larry Rothwachs:

We’re thinking about the same band. I’m actually not holding in Three Doors Down enough to really even say that I know what song you’re talking about, but the song Here Without You, really, it touched me very deeply at the time. I related it, maybe superimposed onto our situation, our relationship. It did become sort of this tagline.

David Bashevkin:

Let’s listen to that right now.

Three Doors Down:

I’m here without you, baby. But you’re still on my lonely mind. I think about you, baby. And I dream about you all the time. I’m here without you, baby. But you’re still with me in my dreams. And tonight, it’s only you and me, yeah.

Larry Rothwachs:

I’ll mention that the correspondence that was going on, in my mind actually, Tzipora was the one who started that pen pal arrangement. When she was not talking to me, I was completely closed out from her. At the time, she had… I think she had a Blackberry. I don’t think iPhones were being used.

David Bashevkin:

Those were the days.

Larry Rothwachs:

We installed, at the time, software, like we did with all of our kids when they were that age, to let us know what they were doing, and maybe on her computer as well. I would rarely actually check it in Tzipora’s case because she had been so shut out from the world. It wasn’t really all that much to be concerned about. We had much bigger problems on our plate. But when she had gone radio silence for a couple of weeks, I was desperate. I was pulling at straws to find anything. What I discovered was she was actually writing a little bit of a journal, a diary to herself. She called it My Miserable Life.

David Bashevkin:

You had a title on your diary.

Larry Rothwachs:

It was called My Miserable Life, and she would add a few lines every day and began to reflect. What happened was absolutely fascinating, because while she was not talking to me, she was talking to herself. I was able to get an inkling, insight, into what was really, really beneath the surface. It was almost like I heard her voice. She’s still there. When you’re talking to her in real life, she wouldn’t give us that satisfaction, but she was talking to me. That motivated me to start to write to her on a regular basis. I was trying to cut through and sort bypass the eating disorder, which is the face that you see, and go deep down and talk directly to Tzipora who’s in there somewhere. There were many, many months and years that she would not really give me the satisfaction of knowing that like we say, the pintele Yid inside of her was really listening and was really attuned to those messages, but she was, and I’m glad.

David Bashevkin:

Is there a specific insight that you gained? The insight of what she was struggling with, what was behind this, what insight did you take from what you had seen?

Larry Rothwachs:

She was expressing tremendous confusion and tremendous fear. Tzipora touched upon this earlier, I didn’t want to interrupt. What’s really, I think, so difficult and challenging with having to see a child through this illness is that the treatment involves a level of care that, again, just seems to go contrary to everything that we know about life in general and parents’ roles in the lives of their children. Can you imagine in any other situation dropping your child off at a hospital and them saying, “Okay, you have to leave now. And we’ll let you know if and when you can talk to your daughter again.” She’s 12 years old, she’s a child. That was extremely, extremely painful. One of the reasons it was so painful is because as this is going on, she’s reflecting to herself and we’re listening to this, that “I am in pain, I am confused. I don’t know why this is happening and I don’t know how to stop it.”

At the time, I didn’t want to let her know. I don’t think until very recently I did let her know that I actually read My Miserable Life because it really was a very private space for her, and I didn’t want her to stop. I was craving that because that would be the only access that we would have to what’s going on deep inside. But in the early days, there was no genuine reflection. There was no, “This is why this is happening.” I don’t believe that she knew at the time why this was happening. I just know that she was afraid and lost and couldn’t control.

David Bashevkin:

Do you mind sharing a little bit? What do you think gave you the language, the words, so to speak, to be able to express what you were going through? I mean, it started when you were so young and you went into adolescence in the middle of this. What do you look at as the breakthrough that allowed you to kind of turn the corner and even have the language to express what you were in the middle of?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Living at home and being with horses and being with my friends. I mean, making friends in the stable.

Larry Rothwachs:

What we basically did was just stop fighting. We just stopped fighting. She came to a point where she was well enough to be at home and basically spent most of her waking hours with horses. We actually owned a horse for a while.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning, a big turning point in this in being able to just figure out what you were going through was developing relationship with horses, animals, and almost developing a new social network.

Larry Rothwachs:

Yeah. I mean, it’s sort of ironic. What happened was, after years of fighting and after years of doing everything we could to impose our will upon her, we came to the realization, with the assistance of really some of the best clinicians in the country, and I say that without exaggeration. Tzipora was under the care of doctors who testified before congressional hearings on these matters. Literally, one of her closest doctors ever once called us when he was in New York being interviewed on the Katie Couric Show, and we actually went backstage and got to spend a little time with him and met Katie Couric. But the point is, she really had the full attention of the best doctors in this country and they said, “Listen, it’s going to be on her terms when she’s ready.”

And so therefore, we made what was, in retrospect, probably the only choice we could make at the time, and that is we’re not going to fight this anymore. She had come to a point where she was well enough to be at home. There were still many concerns we had regarding what she was doing, what she wasn’t doing, but she was able to spend a lot of time with that, which is, at the time, was a great love in her life. And that was horseback riding and her horse in particular.

David Bashevkin:

How does one learn that they love horses?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Growing up, my dad never let us watch anything until we were, I would say, 11. Before, that we were watching Brady Bunch, Punky Brewster, Silver Spoons, Little House on the Prairie…

David Bashevkin:

Classics.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

… Different Strokes. Anyways, this is one of my best childhood…

Larry Rothwachs:

This is awesome. She grew up with the best TV.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Honestly, this is a great childhood memory of mine, coming home every night and watching an episode of Little House on the Prairie. I probably know every episode by heart. Don’t put this in here, but I once dressed up as Laura for Purim.

David Bashevkin:

I love that.

Larry Rothwachs:

Stop saying don’t put this in here.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

No, that’s weird.

David Bashevkin:

It’s totally not.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

But anyways, Laura…

David Bashevkin:

I can tell from your face that it’s not bothering you so much.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

No, it really is. It really is. But Laura had a… I was just very into outdoors and sports and nature. I was a little tomboy growing up.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I like to capture the flag on Shabbos. I’ve always loved animals and horses. And then, I even rode before my eating disorder in Overpeck Park. And then, I started riding horses again during the time. I don’t know what got me into it. I just…

David Bashevkin:

And you can gallop on a horse?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Not anymore.

David Bashevkin:

But you could? There was a period where you could?

Tzipora Rothwachs:

There was a period. Not gallop. You don’t gallop in a stable. Canter.

David Bashevkin:

Canter, that’s the…

Tzipora Rothwachs:

You gallop in the woods.

David Bashevkin:

Got you.

Larry Rothwachs:

Yeah. She actually owned a horse. We had a horse for a period of time. His name was…

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Tucker.

Larry Rothwachs:

His name is Tucker, believe it or not. And when we tell people that, which is pretty rarely, they get confused, “Where does he sleep?” Obviously not here, but there’s a stable not all that far from here. It was a rather costly enterprise, but it’s things that you do when you’re trying to keep your daughter alive. I remember actually once, when I was in Israel, I wanted to buy her gift. What do you get the daughter who has everything like a horse? So I thought I would get a little name plate for his stall. You know how in Israel, they sell those…

David Bashevkin:

The wooden oil…

Larry Rothwachs:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Olive oil…

Larry Rothwachs:

This was just like, I wanted to get a… Because it’s Western themed, I wanted to get a leather name plate. I went into this guy in Meah Shearim who produces these things. I still remember this guy. He was leaning over his machine, smoking like a chimney. And he goes, “Mah hashem?” So I said, “Tucker.” He says, “Tucker?” He was trying to spell it out. He goes, “Im tet, im taf?” I said, “ani lo yodea.” He says, “mah zeh ata lo yodea?” So I said “zeh l’sus” He goes, “ah, zeh lesus? Zeh im tet.”

David Bashevkin:

This is for a horse, you told the guy. That’s fabulous.

Larry Rothwachs:

Tes vav kuf reish and there it goes. There was this name plate, Tucker, over Tucker’s stall. He was, I guess, an extended member of the family for about a year or so. I would say thankfully, because it was a lot to manage on many levels. At a certain point, Tzipora decided she was going to take a break from horseback riding.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I stopped riding horses, I would say, when I reached a point where I overcame everything enough to want to focus on my life in other areas. Horseback riding was everything. I’d wake up in the morning, I’d go to the stable. I’d come back at night, wake up with… It was a whole day experience too. Usually, people go for a lesson and then leave. People at the stable honestly were like my second family.

David Bashevkin:

Wow. We could spend another hour on just Tucker, but I want to come back to our story and maybe reflect more generally. I mean, every parent, every child, it’s so interesting that you grew up watching Brady Bunch, Silver Spoons, Little House on the Prairie. You grew up watching these really idealistic picture-perfect families. That was the picture that you had. And meanwhile, your own story of what you went through is not a Brady Bunch story, is not a Silver Spoons, Little House on the Prairie story. I’m wondering if you could reflect more generally about what this journey has taught you about being a daughter, about family, about your relationship with your father.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

This whole experience brought me much closer to my family and it woke me up in certain areas. It made me realize that family will always be there for you. In terms of my mom, she left her job at one point. I was her full-time job at one point. At first in Princeton, she would drive me, wake up early when I was outpatient. It would be only for the day. She would drive me in the morning and pick me up at night. When I was in Denver, she moved to Denver. When I was in Portland, she lived in the Ronald McDonald. It’s this hotel for free. Anyways, she dropped everything for me. When I was going through it, it was hard for me to see anyone’s help and appreciate anything. But looking back, what my mom sacrificed for me and what my mom did for me leaves me like super grateful.

I’m very lucky. I’m lucky to have my mom and my dad. I got very close with my mom over the past three, four years. I feel that my relationship with my mother got much better. Not that it was ever not good when I had a lot of issues. I think it was very hard for my mom to see me being sick and having an eating disorder. I saw that it was hard for her. I guess that left me a little feeling of guilt, and I felt bad, but it wasn’t something I could control. But my mom was there for me in ways that I definitely didn’t see at the time. I’ve been fine now for seven years, but I would say over the past four years or whatever, I just feel a very strong connection with my mom.

My sister, Shira, got married about a year ago and the chuppa, walk around seven times. Each time, my mom gave me a little squeeze on my hand. And yeah, I’m going to cry too. I cry every day when I think about it. She’s unreal, my mom. She really is. It’s not always easy for me to see the good when I was going through such a hard time, but I feel the squeeze every day now. And I know she’s always there for me, and I see it now more than I ever will or ever would have been able to if I didn’t go through this. My dad is my savior. I would wake up, when I was living at home, I would wake up to yellow sticky notes on the bathroom, like “Have a great day” or something.

These little notes, that’s something super small, but when I say my dad put me first always, he still does, I’m not exaggerating. I found out also a few months ago… I used to email my doctor a lot, and I randomly said to my dad, “She was amazing. She would answer me all the time, very fast.” I would email her a lot, whether it’s “Can I go bike riding now?” Or “Can I go jump on a trampoline?”, ridiculous things. My dad told me a few months ago that, “It was never her. It was me.” He made an email, lesliesanders@gmail.com, and her name is Leslie Sanders, but she had hers with the confidential Atlantic Health. I kept emailing Leslie Sanders, got a response right away, it was my dad saying…

Larry Rothwachs:

There’s a little more to that story, if you don’t mind. In other words, you did actually a lot have direct correspondence with Dr. Sanders. At a certain point, it was just too much for her to handle. So she and I actually conspired together. We were going to set up a Gmail account which I was only going to use for Tzipora because…

David Bashevkin:

She had all these specific and didn’t allow herself…

Larry Rothwachs:

She had many other patients, an extraordinary committed clinician who availed herself to her patients, but…

David Bashevkin:

But Po would want to know every detail to allow herself to do everything and so you conspired with the doctor to set up…

Larry Rothwachs:

That’s the closest I got to becoming a clinician.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

That’s just an example though.

David Bashevkin:

That’s so sweet.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

That’s just an example.

David Bashevkin:

It’s playful too. It’s mischievous in a very sweet way.

Larry Rothwachs:

It required a lot of coordination. That’s one example, and Tzipora only knows some of them. There were many…

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Every year, a new one comes out.

Larry Rothwachs:

… deceptive measures that were needed along the way in order to protect her from herself. While I give myself credit because I think some of them were quite creative, it did require a tremendous amount of attention and focus to keep the facade going, because she is extremely bright, quite manipulative when she’s driven and focused on something, and it really needed to be airtight. It was a plan that was constantly being revised and required a lot of creativity.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

Is there any other ones that you want to share?

David Bashevkin:

I feel like he did… Did you ever read the book Miss Nelson where the teacher comes in as Viola Swamp? I feel like at some point, he came in and he had, I don’t know, a sheital or a disguise, pretending he was the doctor, a white lab coat.

Tzipora Rothwachs:

No.

Larry Rothwachs:

If I could have, I would have with, without a doubt. There was a lot of that, because again, there’s only so much that we were able to rely on others. and you know, bamakom shein ish, that’s what you do.

David Bashevkin:

For you as a parent, how did this change your relationship, not just to Po, but your relationship to being a parent in general?

Larry Rothwachs:

I think that this entire experience obviously opened our eyes and our hearts to a world that we really hardly knew existed. After I started to really face the challenges associated with managing an eating disorder close up, I actually reached out to some of my congregants who had come to me over the years to discuss matters of eating disorders and begged them for forgiveness for failure to have really understood what they were asking and why they were asking it. As much as I’d like to think that I was somewhat experienced and trained and understood different areas within the realm of mental health in general and eating disorders in particular, I had to really live through it to understand and to appreciate how little I knew. I think that that experience in itself was really good because it redefined the contours of my life in general, my career.

Several years ago, I returned during the summer to school to earn a degree in social work. Actually was licensed this past week. Not quite sure what I’m doing with that, but in other words, I think in Tzipora’s zechus, I’d like to think that I’ve been able to be more focused on an area that really requires constant awareness, particularly within our community. I would say more importantly than that, this entire experience led to tremendous self discovery. I was able to explore worlds with inside of myself that I never knew existed. Needless to say, it hasn’t been said yet, but I say it with tremendous pride, my wife and I benefited tremendously from the assistance of a therapist who worked with us on and off throughout this entire ordeal. That was my first exposure to therapy. And if I had all the time and money in the world, honestly, I would continue to work with her or with another therapist at every stage in life because I found it to be incredibly worthwhile.

You really have to experience sometimes some really, really, really challenging moments to understand and appreciate who you are, and finally, I guess, what life is all about. When things are relatively simple, when things are… There’s sort of the everyday challenges within life, so we can afford to look at life in a very binary way, “This is good, this is bad. It’s cloudy, it’s sunny. This is a nice person, this is a not nice person”, without nuance, without appreciating the complexity of life, and I would say that throughout this ordeal, we have come to understand and to appreciate that nothing in life is simple. Quite everything is complex. It took a challenge like this for us to really, truly understand that and appreciate our relationship. Our relationship with Tzipora is unique. I love each and every one of my children.

I would never say, and I don’t believe for a moment that I have a better relationship…

Tzipora Rothwachs:

I’m a hundred percent his favorite.

Larry Rothwachs:

It does say on my phone Po, my favorite daughter, but that’s only because I allowed my kids to enter their names however they choose. I wouldn’t call Tzipora my favorite daughter. Our relationship is unique. We experience things together that I have never, and I hope never to have to experience with any one of my other children, and as a result, our perspective on ourselves, on each other, on life in general, has been shaped and defined by some very, very unique experiences. The good, bad, and the ugly.

David Bashevkin:

If you could go back and give your younger self advice of what you were going through, what would you reach out and tell that younger father, that younger Larry Rothwachs, who is about to confront this, who’s in the middle of this, what advice, what chizuk, what encouragement would you tell yourself?

Larry Rothwachs:

Yeah, I guess I would say two things. The first one is some very, very sagely advice that I have heard many, many times from one of my Rebbeim, Rabbi Willig, shlita, who whenever discussing with him matters having to do with chinuch in general, and I certainly think it applies in this particular, he always says “Patience, patience, patience.” I think that as parents, we sometimes become very fixated on wanting to see our children be what we imagine for them, what we expect of them, at certain stages and phases in life. Sometimes their expectations are completely inappropriate and off base, but even if their expectations are in fact appropriate, that’s just not the way life works. And so, to understand and to appreciate that you are about to embark on a journey in which you are going to feel as if all is lost, as if you will never see the light of day again, and to just be able to speak to myself in the most reassuring way and hear the words and internalize the words, patience, patience, patience.

There’s one other thing I would say, and I’m actually going to read a note. I’m not going to name this individual because I don’t know that she wants to be named, but in a letter that I wrote to Tzipora, 10, 11 years ago, I wrote the following. I said, “A few months ago when you first went to Princeton, I was afraid. I said to a close friend that I can’t handle this test. And this is…”

… I was afraid and I said to a close friend that I can’t handle this test. This is what she wrote to me in an email. Very simple. She wrote, “I am a firm believer that HaKadosh Baruch Hu gives people challenges that he knows they can deal with. Even if in the moment, they seem insurmountable. The real intent is that HaKadosh Baruch Hu needs you to do something … Needs you to do something with it after you have … I’m sorry, after you have mastered your situation. The way I see it is that you, Chaviva, your children, and most important Tzipora are going to make a difference in the world years from now. When this is all behind you, there is no way to see it. Now, you have to …” Come on. Where’s this coming from? “You have to hang on to the professionals and continue to talk to God.” You know, when I look at this now and I read this and as you could see, it was a little hard for me to read it. This is simple. I could do a much better job. I could actually clean this paragraph up and maybe stick a couple of marei mekomos in there and make it-

David Bashevkin:

Scholarly rabbinic.

Larry Rothwachs:

Sound so much more profound, but I cannot tell you how much I held onto this at the time. I read it again and again and again and again, and wanted so much to believe that there would be a purpose to all of this. I will never say, it’s not my place to say, nor do I think … It would be presumptuous of me to say that this was all worth it. That if I could change anything I wouldn’t. At the end of the day, this is so much more about Tzipora than it is about me. I can say that these words, to a certain extent, I do believe were somewhat prophetic because I really do believe that my life, Chaviva’s life, Tzipora’s life, the life of our entire family and by extension, I really do think many other people have been inspired by Tzipora’s transformation. By incredible resilience and her ability to face one of the most frightening experiences imagined as a child and being able to emerge strong, secure, focused, and determined. Frankly, and I’m just going to say one thing. David reached out to me about a month ago and said, “I’d like to interview you and your daughter.” I said to him, “Which daughter?” He said the one who had a eating disorder and I said, “I’d love to, but she’ll never say yes.” He said, “Just ask her.” I said, “But she won’t say yes.”