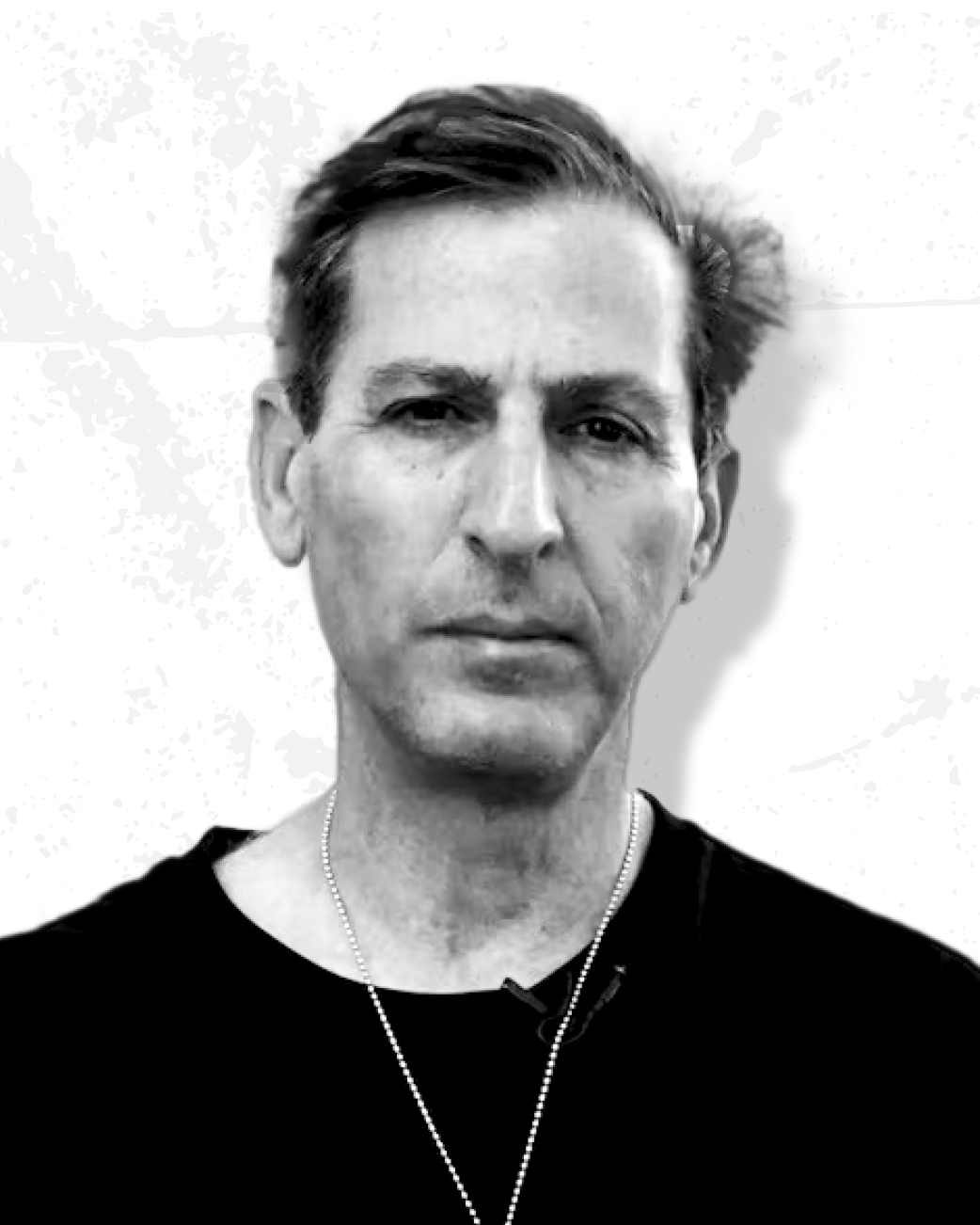

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

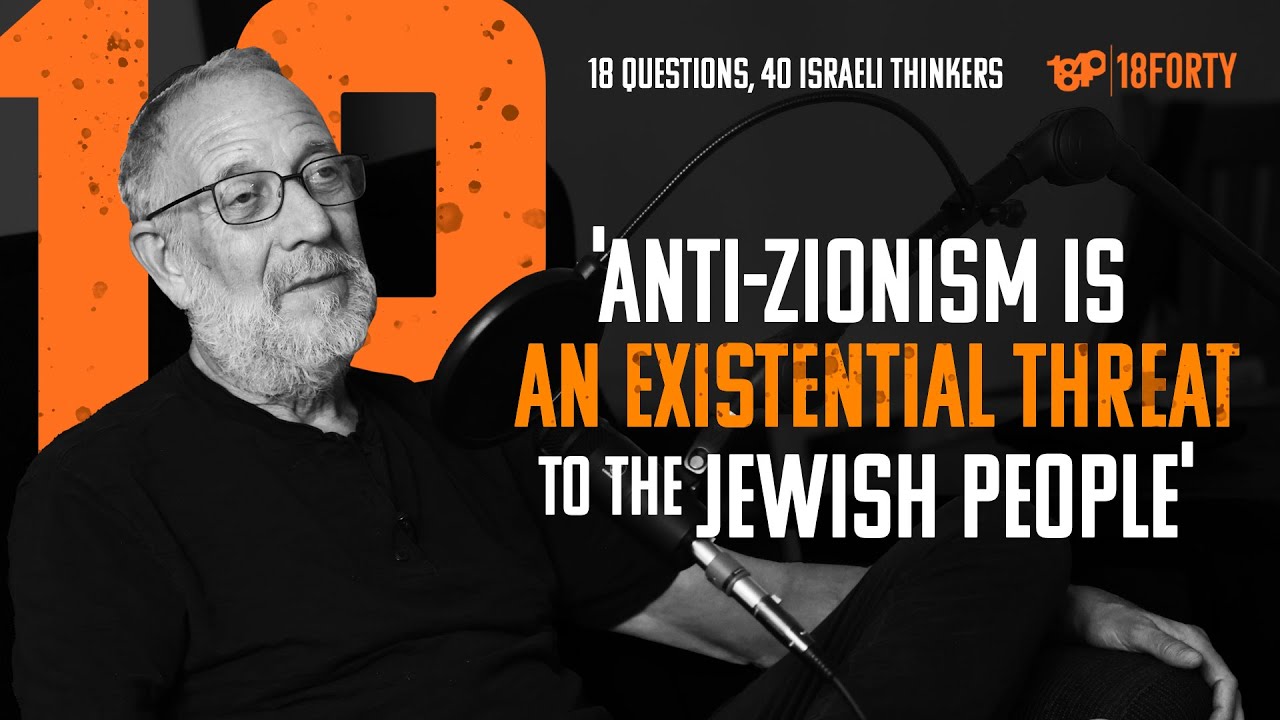

Summary

Until Hamas is gone, Haviv Rettig Gur says, Gaza will be unable to recover after the war.

The Times of Israel journalist and political analyst has emerged as a leading voice for the Israeli public and the Jewish world for deeper understandings of the war’s developments. Haviv has covered Israeli politics — domestic and foreign — for nearly two decades and speaks internationally about Zionism, the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict, and Israel’s future.

Haviv was previously the director of communications for the Jewish Agency for Israel, and currently teaches history and politics at Israeli premilitary academies.

Now, he joins us to answer 18 questions on Israel, including the country’s leadership, Western media, and the Palestinian future.

This interview was recorded on Sept. 9.

Here are our 18 questions:

- As an Israeli, and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

- What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in its war against Hamas?

- Do you think Western media covers the Israel-Hamas War fairly?

- What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

- Which is more important for Israel: Judaism or democracy?

- What role should the Israeli government have in religious matters?

- Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

- Now that Israel already exists, what is the purpose of Zionism?

- Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

- Is the IDF the world’s most moral army?

- If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

- Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army — such as in the context of this war — be a valid form of love and patriotism?

- What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

- Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

- What should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict after the war?

- Where do you read news about Israel?

- Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum, and do you have friends on the “other side”?

- Do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish People?

Transcript

Transcripts are lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

Haviv Rettig Gur: A lot of people talk now in the West, these sort of very moral, very tormented people, about a one-state solution. I think that’s adorable. It’s just, how could people who can’t trust each other enough to have two states suddenly have one state? Why would the Jews, after the 20th century, give up their capacity to defend themselves, which is what a one-state solution is? Why would the Palestinians, who will enter this one state massively, with a huge gap in economics and power, possibly trust the Jews? All the Palestinians know is that you can’t trust the Jews. The Jews are expansionist and all that, right? That’s their discourse about us.

It’s a very silly idea. Hello, this is Haviv Rettig Gur. I’m a political writer based in Jerusalem with the Times of Israel. This is 18 Questions for 40 Israeli Thinkers, plus me, from 1840.

Sruli Fruchter: From 1840, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Shirley Fruchter. 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a new podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas war, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today.

Haviv Rettig Gur is a journalist and political analyst whose public profile has skyrocketed in the last 11 months. His sobering voice of reason, substance, and nuance is why I believe he’s become such a figurehead today and such an important voice and person for those seeking deeper explanations and perspectives on Israel’s war with Hamas and the state of the world today. More formally, he’s officially a senior analyst at the Times of Israel and has covered Israeli politics, foreign policy, Jewish diaspora, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and everything else that goes along with this since he’s been a journalist. He has reported from over 20 different countries and delivered lectures in Israel and abroad on Israeli society and its history, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the future of Judaism, and the future of Israel and Zionism.

Before he worked at the Times of Israel, he was the director of communications for the Jewish Agency for Israel. And in addition to his role at Times of Israel, he teaches history and politics at Israeli pre-military academies. I first heard about Haviv actually from one of my rabbis when we were talking about the different types of journalists and outlets that we tend to follow and rely upon to understand what’s going on with Israel. After our conversation, when I first listened to an interview with Haviv, I knew that he had to be someone we had on the podcast.

One of the things that I’ve very much appreciated about his perspective in general, and I think this really comes from his experience as a journalist and as an analyst, is his tendency to provide a lot more information and context and an overview than you might initially expect when probing a certain topic. At many points in our interviews, there were a lot of directions he was going in where I wasn’t really sure it was going to tie in. And then I saw why, and he speaks about this and you really get this sense, comes across from him and he’s a very big advocate of this, of understanding deeply, deeply understanding history, context, and the information that surrounds the topic that one is looking into. Specifically, it comes up in the interview when we’re talking about Western media’s coverage of the Israel-Hamas war, and he gives an example of speaking with a journalist, trying to understand the motivations Iran has towards Israel and how the journalist’s reluctance or inability to try and ask that kind of question hindered the journalist’s ability to report for her or his readers.

This interview was our longest, so although Yossi Klein Halevi was at the top of our charts for the longest interview, which came out two weeks ago, this is now our longest because there was, as usual, too much to discuss, so I’m trying to keep this introduction much shorter than usual. But in brief, if you want to find out more about Haviv, you can easily search him up, find out more about him on Times of Israel and YouTube and the different podcasts that Times of Israel has had where he is a frequent guest. So on that note, if you have questions you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, shoot us an email at info@18forty.org and be sure to visit us at 18Forty.org where you can find all the questions that we’re exploring about Jewish life today. And special shout out to the 18Forty Podcast, our big brother, our big sibling, who was exploring the topic of Teshuva, which began last week.

Be sure not to miss that. And so, without further ado, here is 18 Questions with Haviv Rettig Gur. We’ll begin where we always do. As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I’m feeling okay.

Sruli Fruchter: Why okay?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I was going to make this one of the short answers to earn time for the future questions. Speak freely.

Sruli Fruchter: The bank is infinite.

Haviv Rettig Gur: We are the strongest Jews who have ever lived in the history of Jews.

Obviously, we’re okay. We just have this culture of anxiety and tension and worry, but we’re okay. We have enemies who think they can destroy us. We have enemies who have set about destroying themselves on the altar of destroying us.

That’s horrifying and tragic and sad. It’s not going to destroy us. We’re okay. Every generation of Jews that came before us worked and suffered and bled to make us, to give us the strength we, this generation, has today.

We are so strong that we’re actually startled at the fact that there might still be such a thing as war and fear and enemies and big religious ideologies that come for you because you play some role in a big moral historical cartoon running in their own heads. And that surprises us, but that is the basic experience of most generations of Jews at one point or another somewhere. So, welcome to Jewish history. No one has ever been safer and stronger navigating these challenges than this generation.

Our one task is to realize that and do whatever we need to do to make our future safer, face down these enemies. There’s some way to even cure these enemies of their need to destroy us, but we are emphatically okay.

Sruli Fruchter: It’s interesting because I was just hearing you on a different podcast with Times of Israel.

I’m going to get her name wrong. What is it, Amanda? Borschel-Dan. I usually get it right.

Haviv Rettig Gur: She’s Borschel and her husband is Dan. Barak Dan. He’s a linguist, a very interesting man. Oh, wow.

Sruli Fruchter: And on that podcast, you were describing that the vast majority of Israelis are actually quite pessimistic and quite not okay right now. So, I’m curious, not so on the nation, but on yourself, why you’re feeling okay. Yes,

Haviv Rettig Gur: There is one great Achilles heel that is tearing us apart and is our one weakness. And if we fall, that will be why we fall and it was ever thus.

And that’s our own internal schism, political campaigns that are campaigns against each other. I believe the current chief perpetrator of this inner weakness are the people in power, not because I have something against them, but because they happen to be in power. And so, they happen to be the ones doing this. If the other side was in power, I suspect there would be similar things happening from their end.

But there is, among the Israeli public, if you go to the protests for a hostage deal and you scratch the surface and you talk to them and you interrogate them a little and they welcome it, you will discover that they do not want Hamas to win. You will discover a great many veterans of the Gaza war who are willing to go back into Gaza. You will discover a group of people who, according to the best polls we have just from this past week, a large majority are willing to go fight a war against Hezbollah in Lebanon, because they have emptied the north. But they don’t trust the government.

They don’t trust our leaders. And if you follow the news and the statements, forget the news, the statements coming out of our leaders, they haven’t earned that trust. And they haven’t earned that trust for quite a while. Every group of Israelis I am familiar with is impressive, except them.

And so, yes, our inner distrust of each other, our inner divides as Jews, as a society, as a polity, that is our one weakness. And the people perpetrating this weakness upon us are hurting us. And I don’t like them for that reason. But then when you ask the Israelis, what about the enemy? You discover astonishing unity, strength and courage, frankly, power.

We are dangerous. And if we had better leadership, I think the region would be less eager or less willing to experiment with this idea of maybe they can destroy us, because our capacity and capability would be more evident in the region.

Sruli Fruchter: What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in the current war against Hamas?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Interesting question. I think the greatest success, in my view, a little contrarian view, is what all the sort of Western intellectual class is convinced is our greatest mistake.

Hamas built a battlefield. It built hundreds of miles of tunnels in order to transform Gaza into a type of battlefield, all of Gaza, with its civilians. And its civilians are functionally critical to the battlefield Hamas produced. The point of those tunnels is that we have to go after them through the civilian population.

They run along streets, they don’t run out into fields anywhere in Gaza. And in 11 months of war, not a single civilian has been allowed to step foot in a single tunnel. The point is to force the Israelis to destroy Gaza. And Hamas is upset at this moment that the death toll in Gaza isn’t much higher.

And if it was higher, Hamas believes, Sinwar believes, Hamas would be winning much more clearly. In other words, the pressure on Israel would be an order of magnitude greater, the price for Israel would be greater. Hamas wants to win a war against Israel through the destruction of Gaza. And after October 7, after seeing those videos of those Hamas attackers, infiltrators, kill parents and then sit down to eat food from the fridge of the home while teasing the children over their dead parents.

After watching these people, the Israelis are willing for the first time, they have not been willing in the past, to pay the price Hamas set for destroying Hamas. And the world concluded, all these experts of war and the Institute of War in places like Columbia and Princeton and Harvard and in the media in the West, concluded that that was a great Israeli mistake. Hamas managed to force, impose on Israel a war that hurt Israel terribly. I submit to you that it is a horrifying tragedy.

Hamas built the battlefield, Hamas set the price. We have to now show that we can win, not on our terms, not the war we want, a war of maneuver of tanks in the desert, the war we are classically brilliant at, but that we can win their war, on their terms, in their battlefield, with the cost they impose. And we will still be standing and they will still be destroyed. And the fact that the Israelis, with grim determination, were willing to go do that, the cost for Gazan civilians is the astonishing thing, is the horrifying thing.

But the fact that we will fight them on their terms and win. Iran built Hezbollah for no reason except to be that second front. And so we have to be able to hurt Iran and Hezbollah with that second front. We have to be able to take every blow they can dish out and we have to be able to defeat them on those terms, on their terms.

And then they will be lost. They are a new strategy, born in the failure of several old strategies that we defeated, again, on terms they imposed. And we have to do that again. And so the greatest Israeli success is the willingness to fight them on their terms and still do what needs to be done to win.

The greatest Israeli failure, we just talked about. We have a political class that never, never joined us in the war. When family betrays you a little bit, it hurts a lot more than when a random business partner betrays you a lot.

Sruli Fruchter: When you say political class, ar e you talking about, I’m just imagining it horizontally or vertically, the horizontal line being people on the upper echelons of the …

Haviv Rettig Gur: My wife accompanied a family that had eight members taken hostage on October 7th. A friend of hers is a sister of one of the hostages. And that family managed to get a meeting with the chancellor of Germany, because I think, I don’t remember exactly, I think two grandparents had citizenship before they could get a meeting with the most junior Israeli minister. I went to a funeral of a soldier in Gaza.

Ministers came to the funeral because dad, the father of the soldier, was politically involved and fled after the eulogies so that they wouldn’t accidentally rub elbows with people who they know hate them. So they flee. Kibbutz Nir Oz, one quarter of the kibbutz, was killed or taken hostage on October 7th. They have invited Netanyahu to visit, and he has refused.

11 months later, he has not yet visited. We have a political class made up …

Sruli Fruchter: Political class, you mean the…

Right-wing leadership. I mean, unless you’re speaking … That was my question before.

Are you referring to the left and the right, and it’s the higher option—

Haviv Rettig Gur: in those camps? They are right-wing. That makes them abject coward. I don’t think that’s it. We have polls of trust in which the least trusted politicians in Israel come from Likud, and also the most trusted come from Likud.

I don’t think the public, the feeling of them failing us, I don’t think is partisan. Obviously it’s externalized in partisan ways, and obviously different political partisan campaigns are running partisan campaigns about it. But they failed us, disastrously. Imagine being prime minister on October 7th, and 11 months later, still thinking it’s everyone else’s fault, after the strategy was yours and you ran the place for 13 years.

Is that really what the right can give us? Can the right really not produce another leader? Can the right really exact any kind of cost for October 7th? The containment strategy defined Netanyahu. He defended it. From the far left, they argued that we should lift the blockade. From the far right, they argued we should go in, and he defended the containment.

Of Hamas in Gaza, and when it failed, right? So I would say it’s a right-wing failure as such, if it turns out that the political right, the voters, ordinary people, forgive him. If they decide in the name of the partisanship and the great war on the left that everybody imagines on the right, and just like there’s a great war on the right, which is coming for our democracy, everybody imagines these great enemies on the other side. If in the name of that imagined enemy, you forgive the leadership on October 7th, then yeah, it’s a right-wing problem.

But that is our great weakness. And we have almost no other weaknesses.

Sruli Fruchter: Weakness or mistake?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I think that’s a terrible mistake. I think that’s a terrible mistake, that the prime minister on October 7th is the prime minister 11 months later, I think is a terrible precedent and a terrible lesson for the future for this country.

And it’s also unjustified. I’m deeply unimpressed by this government. I don’t think it’s produced the results we want, not in the war. I don’t think it’s handling the economy responsibly.

I think that the debates in our, I can defend this with a lot of details. When you have now a budget debate happening today, the day we record, there’s a budget debate happening between Bezalel Smotrich, the finance minister, and the Shas party. And there is no sense that there’s a war on. And there’s no sense that there are hundreds of thousands of Israeli households that have crashed economically.

And they’re talking about the same old yeshiva budget increases, because they’re in the coalition and you need their votes. I don’t know what to do with that. Likud has an enormously high percentage of people in the war, voters who are actually serving in the war. They don’t seem to take care of them.

And because Israeli voting is so tribal, I’m not sure the voters will exact a cost. And that is their absolute God given democratic right. But that’s our weakness.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think Western media covers the Israel-Hamas war fairly?

Haviv Rettig Gur: It’s a complicated question.

I don’t know what fairly means. If a reporter for The Washington Post or New York Times or I don’t know what Chicago Tribune shows up in Israel, and their automatic take is anti-Israel, that’s not necessarily unfair. And it’s not unfair because there are thousands of dead children in Gaza. In other words, they could look at the situation, they could see the disparity in power between Gaza and Israel.

The Israelis feel vulnerable in the face of a vast ring of proxies of Iran, and they know Iran is funding Hamas. And so they feel vulnerable and small and weak compared to the enemy. But Palestinians and certainly Gazans feel that weakness compared to powerful Israel. And they could look at that disparity and they could look at the civilian toll in Gaza.

And they could say, my first duty as a journalist is to make demands of the Israelis. And that’s fair. That’s journalism. My concern isn’t that it isn’t fair, my concern is that it’s profoundly ignorant.

And it’s not just ignorant, it’s uninterested in ending its ignorance. So you will peruse the pages of the Western press, watch the television interviews, and you will not really understand, you will never really discover why mentally healthy people in Hamas, not sociopaths, not psychopaths, a lot of people think there is some sociopathy or psychopathy in Sinwar himself. But Sinwar alone can’t, couldn’t have destroyed Gaza and couldn’t have carried out October 7. Why they do what they do? Why is Hamas willing to destroy Gaza? The question I actually asked a journalist from the United States when I was berating them about their lack of curiosity was, Iran has no border with Israel.

It has no interests in Israel. Why is it spending a vast percentage of its GDP? Why is it losing so much, incurring so many sanctions, spending so many billions it doesn’t have on destroying Israel? And when you answer that question, don’t answer it with one of these shortcuts journalists take, this sort of vocabulary to avoid. d answering, for example, calling them hardline, or calling them extremist, or what is the actual story they think they’re living in?

Sruli Fruchter: What did that journalist answer you?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Nothing much, nothing much. They understand, and my theory of what the Iranians are doing, which I think is very clear, the Iranians talk about it, but also is old and is well known and is so obvious in this region that people barely even bother talking about it, is just my take, and they were very, very defensive.

They didn’t know why Iran is so obsessed with Israel, and they don’t care. It’s just a fact of life, and journalism is what happens after you accept that fact of life. To me, it’s fundamental, because if you understand why the Iranians are so obsessed with Israel, you understand a lot about the regime, what it thinks about itself, where this war is going to go, whether you can deter them or not, basic empathy and understanding of the enemy’s sense of self and story and motivation. I mean, you don’t understand a war without it.

I don’t know why this is a complex point, right? This is ancient, ancient, this is Sun Tzu wrote stuff like that. This is not interesting wisdom, okay? But there’s a profound lack of curiosity. The Western press suffers from a sense of itself as a moral vanguard, and therefore the fundamental question it asks in every issue, in every place, in every problem, every conflict, every political crisis in America, is as a moral vanguard, because I am the rabbis and priests and philosophers of my society, rather than the journalist who’s supposed to explain it analytically. I have to tell everybody what to feel and think.

And that makes them into deeply uninteresting, uncurious people, incurious people, who can’t actually reflect what actually, you know, when an Israeli reads The New York Times, before they get upset or not upset that the headline could have been more pro Israel, more anti-Israel, more this, more that, they don’t see themselves in the story. They don’t see their experience in the story. The story of the protest against the government is not, haha, Bibi’s about to fall, which is the question I got from multiple Western journalists in Jerusalem over the last week. Is Bibi about to fall? When is he about to fall? How does he fall? What’s the procedure? What’s the parliamentary process? And I said, guys, talk to the protesters.

Bibi’s not going to fall because this is a fight over the Philadelphi Corridor, which most Israelis who hate Bibi don’t want to leave the Philadelphi Corridor. In other words, learn the people. Talk to the actual experience of the people. If they can’t see themselves in your story, you’re not doing journalism.

You’re just, you’re talking to a mirror and surprising yourself by your own eloquence. So it’s not, I think that they’re unfair. There’s something much deeper there. I don’t think they’re failing Israel.

They’re their readers and they’re failing their readers on vastly more issues than us.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Bribes. I take bribes, mostly bribes. No, I don’t tell people anything about who I vote for.

I will say I am. Not who you

Sruli Fruchter: vote for, but what you look for. What things are you considering or hoping you’ll see reflected in a party?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I would say competence, honesty, not political honesty. I don’t want every politician who makes a promise on the election in an election campaign to fulfill that promise because then the country would go bankrupt.

But a fundamental coalition building honesty. Netanyahu right now suffers from, there’s this, when you talk to Likudnikim about how if Netanyahu’s replaced, they’d have an easier time forming a government, not a harder time. Because, you know, a Gallant or an Edelstein or a Barkat or Israel Katz is trusted. They think that across the aisle they can sit in a government with them.

Netanyahu’s entrusted. And then they say, well, you can’t boycott somebody supported by, you know, voted who gets 25% of the vote. And then I said, but they didn’t boycott. They went with him to a rotation coalition government and then he stabbed them in the back on national television after promising us no tricks and no schticks back in March of 2000 with a rotation government with Gantz.

And so nobody’s, he’s lost the capacity to sign a deal because everybody knows he’s lying. Everybody knows that everything in the deal is a lie. And that is not something you hear from Yair Lapid, who thought it was a lie back in 2020. That’s something you hear in Likud. And a lot of frustration about that. So look for a kind of basic deal making honesty, because we have never had a majority party government.

There’s never been a party that had a majority of the Knesset. It’s always coalitions. And a basic integrity will build the better coalition. And the coalition, you probably want more and the person with integrity will have more options and therefore will have more influence.

Netanyahu’s a weak prime minister within his coalition, because he has no one he can bring in to replace any other partner. And so all the partners can get whatever they want on any issue they care about. And that’s a profoundly weak position to be in. And if he had other options, because he had that integrity, he would be stronger and the government, the weight of power in the coalition would be more with him.

So a basic integrity I think is useful. It’s just tactically, politically useful. And competence, you know, we sometimes have been led by very competent people and sometimes by much less competent people. The good news is, just about every party among politicians I know, and have tracked their careers and policies, has a front bench with good people.

Likud, Yesh Atid, these are serious people. Meretz, the Democrats, right, the Meretz-Labor federation, they’re very good, serious, honest people. Some of the finest ministers who have accomplished the most and who have gone from this government to the kibbutzim and who have sat with victims of October 7 and not chickened out and run away like the cowards that they are, the ones who have not been cowards, came from Shas. If the policies and the basic sort of worldview fits you, right, if you are economically, let’s say socialist, religiously conservative, and are lo oking for a competent government, Shas is not a bad option.

So I am capable empathetically of understanding or personally even of voting for probably 80% of the Knesset.

Sruli Fruchter: is more important for Israel, Judaism or democracy? I

Haviv Rettig Gur: Which don’t know what that means.

Sruli Fruchter: Which part?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I don’t know what the question means. I don’t know what Judaism means for a state.

And we don’t entirely know where democracy, Israeli democracy even comes from. Israel has to be a democracy. If it isn’t a democracy, it falls. I don’t know how to put this more bluntly, so I’ll just put it this way.

I have been being, my oldest is 13. In five years, he’s going into the army. I’m okay with my four children going to an army where they might actually have to fight a war. Not all armies in the world have to fight wars.

I’m okay doing that, even though they are the most important thing in the world. I want to be very clear on this. Israel exists to protect them. They don’t exist to protect Israel.

And therefore I’m okay sending them to an army to protect Israel, only because other Israelis are sending their kids to the army to protect them now. And they will take their turn in this joint effort to protect each other, which has made us the safest Jews who’ve ever lived. And that’s only possible in a democracy. If the next war is Putin’s war in Ukraine, the dictator needs the war for some wackadoodle geopolitical reason and is willing to kill the quarter million of our kids for that vision, then Israel won’t have my children and they won’t have those soldiers willing to go into Gaza.

There was some statistic from the army, something like 18% of the reserve army is high-tech employees. High-tech in Israel votes overwhelmingly left, center-left. The left went to this war just as much as the right. That unity in the face of enemies is only possible if everyone’s a stakeholder.

And if there isn’t actually the belief, what crashed, the reason morale has crashed on the center-left over the last 11 months, roughly about six months ago, we can track it in the polls, is that they no longer actually believe the war is being run for military, decisions are being made for military purposes, but in fact, they’re political decisions. Netanyahu’s politicking is that that collapse of trust in government has collapsed morale in the center-left. I disagree with that analysis of Netanyahu’s behavior. I think it’s incompetence and weakness that made us stop in Gaza for three months because of American pressure.

I don’t think he was literally campaigning and that’s how those decisions were made. And governments that make not-perfect decisions in wartime is kind of a feature of war. In other words, I disagree with their analysis, but my point is only that the sense that the war is actually necessary and that the people are united around a leadership that even if they’re partisan, nevertheless, are leading the country as an elected leadership is foundational to the ability of the state to demand from us great sacrifice. And without great sacrifice, it won’t stand.

And with a willingness to great sacrifice, we don’t actually have to sacrifice that much. So Israel, the day it stops being a democracy, stops winning wars and collapses. So it has to be a democracy.

Jewish. This is what, to me, the least interesting question in our public life. And I have a secret suspicion that everyone who deals with this question is lying. What the heck is a Jewish state? And who cares? There’s never in the history of Jews been a chief rabbi until the goyim imposed it on us. And now it’s this holy thing we all have to bow before.

I don’t know anyone who respects the chief rabbinate. I don’t know anyone who respects the chief rabbinate. I mean, we’re meeting in the OU building. So Religious Zionism has a deep old reason for respecting the institution.

Ask them about the rabbis and you won’t hear that deep old reason. There have been great chief rabbis. Rav Ovadia Yosef was a great rabbi and a true genius and a true leader and a man who forged new identities out of populations of Jews. And when he passed away, 700,000 people felt the need to be at his funeral.

Jerusalem was doubled in population for a day, but not because he was the chief rabbi, because he was Rav Ovadia Yosef. It’s actually startling to people that such a great man could have become chief rabbi, right? Because that’s not who becomes that. So the whole idea of a Jewish state, if the state is full of Jews, it’s going to be a Jewish state. You walk down the street and yell at somebody about why they’re wrong, you’re a Jewish state.

Sruli Fruchter: What role should the Israeli government have in religious matters?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I like religion. I think religion asks questions that nothing else asks and science can’t even begin to tackle. And so as little as possible, as little as possible, what are the three things you love most in this world? And do you want the government touching them? As little as possible. Israelis love their religion despite the state, not because of it.

And they don’t actually live in the official legally sanctioned religious institutions of the state. I think 50% of Israelis tell pollsters, there was a poll on this a month ago, 50% of tell pollsters, they don’t want to marry in the state rabbinate. 50% of Israeli Jews, right? There’s whole different numbers for the Sharia rabbinic Kadhi system, right? For the Muslims, and the canon law system for the Catholics, we have the old Ottoman millet system. Because they don’t want to marry, they will build workarounds.

Because you can’t actually force people to do religious things. So for example, we have in Israel, totally invented by the courts, not by the legislature and absolutely beloved by the Israelis and no political party, however religious, is going to ever touch it because they know that they can’t. We have a common law marriage in Israel. Because you cannot, there’s no civil marriage and you have to marry in the old Ottoman system.

Everybody hates the old Ottoman system. But nobody can agree on what to replace it with. So it just sticks around generation after generation. This is a problem in many Middle Eastern countries, not just Israel.

Lebanon has this problem exactly. And so we’ve developed a common law marriage, which is, we use the old halakhic term, known to the public. It’s functionally basically English common law marriage. And the courts have slowly grown out the rights that this recognition, which is usually post facto, right? When a couple lives together for many years, sleeps together, that’s part of the definition, shares a bank account and then breaks up.

And then one of them sues the other to help them finish the rental contract. Then they discover they had been married because that’s how common law works, right? We have given those relationships called yeduim betzibur, known to the public relationships, the powers of end-of-life decision, the power to sue for alimony, the power to adopt children, the power to receive the stipend of a wounded or killed in action soldier. And we have extended that in the 90s to gay couples. So right up until the US Supreme Court forced all states to recognize gay marriage in 2014, I think it was, Israel had both the most conservative, reactionary, literally imperial Muslim Middle Eastern marriage law in the free world.

And also one of the most liberal, all at once, overlapping each other in these oddball workarounds. That’s what happens when the state tries to take over religion. Everything goes nuts. It’s not a healthy situation.

People will live their ordinary lives. If the state wants to control religion, it will fail. It doesn’t really want to. It’s a game everybody plays.

I don’t think it’s interesting or useful. The sooner the state gets out of religion, the stronger religion will get.

Sruli Fruchter: Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Absolutely.

Sruli Fruchter: No distinction in terms of army, in terms of religious differences?

Haviv Rettig Gur: No, there need to be other options to the army.

There needs to be a serious community service option. A great many people will take that option among Jews. Not everybody’s built to be a soldier.

Sruli Fruchter: Isn’t that already available with Sherut?

Haviv Rettig Gur: There’s a Sherut Leumi system, a national service system.

It is a few tens of thousands of kids. It’s not nearly what it should be. It needs to become mandatory for everyone as a condition for entering university. It needs to be local.

In other words, you can choose to do it in your community. So every young Haredi person can do it in their community. Every young Arab person can do it in their community. And it needs to give us a workforce of kids who are taught that society is something you serve.

That volunteering isn’t optional, which is a funny thing to say, because that’s literally the definition of volunteering. But that in fact, you don’t live without society. You look at the West today and you see just a social and emotional wasteland. An entire civilization of people desperately lonely, measurably.

Reports from the CDC talking about epidemics of loneliness. Well, what is that? It turns out that that is the ideologizing of everything and the removal of actual human contact. Americans no longer really have churches and social clubs. Increasingly, there are obviously huge numbers of Americans with, but this is true in France and Britain and Canada and Australia.

These old ways of gathering and these old ways of meeting and these old support systems have disintegrated over the last 40, 50 years. And people live these lonely, disparate, detached lives. They’re incredibly mobile societies. They leave, they move out of their city, out of their county, out of their state.

The kids go across the continent to go to college. And so they end up also because the grandparents are far away, having fewer kids and having smaller families and being terribly lonely people and societies. Some wonderful statistics that really are so startling when you think about it. Progressives donate much less to charity than conservatives.

I think that’s interesting, not because I want to rib on progressives at all. I think what progressives think they’re doing, and this is a conscious discourse among progressives, is that they want systemic solution. They want to actually solve the problem. And you do that with voting and political power.

And if you donate, that’s a Band-Aid. So they don’t donate, they march. But donating profoundly affects who you are and how you think of yourself. And donating can be time and donating is socializing.

It’s a socializing experience. And so they have very few socializing experiences.

Sruli Fruchter: So just to tie us back to the original question.

Haviv Rettig Gur: I was hoping to avoid the original question.

Sruli Fruchter: It seems like you’re saying that yes and no.

Haviv Rettig Gur: We need to teach our kids that society is whatever they build here and now in their community, in their street. Now our kids includes Arabs and Haredim and communities that don’t go to the army. The army is this vast socializing experience.

The army makes people live happier lives. Not on purpose. That’s not why we built an army. It’s an awfully expensive way to do it.

But it ends up doing that. And we need to have every member of this society believe they’re a stakeholder in it. And that’s a great way to do it. And we also need to create a real sense that a fairness, frankly, a fairness.

There is nothing in the Haredi community that prevents them from taking over the entire army medical corps. The biggest medical nonprofits in Israel are Haredi. And if we had a, if everyone was accustomed as a fundamental aspect of Israeli life, you pay taxes, you give a volunteering couple of years, and they would build whole learning institutions to accommodate in the hours around that volunteering. It would be doable if it was a demand.

And there wouldn’t be the army lifestyle is going to make us secular. And therefore we’re scared of the military. It’s not good for our religious lives. All of that wouldn’t happen.

And in the Arab community, there’s a lot of complexity because there’s a lot of layered identity. There’s a sense that they’re Israelis. There’s a sense that they’re Arabs and Palestinians and Muslims and all these different identities intertwine and overlap in different ways. And they vote differently based on what they prioritize among those many different identities.

So a localized sense of commitment and contribution would strengthen, A, the communities themselves. The communities need an army of volunteers. They need commitment. They need, it would lower crime.

It would pull some of those young people out of, you know, lacking work, lacking, you know, being drawn into organized crime, which is a huge problem in the Arab community, much more so than in Jewish towns and communities. Yes, we need it. And we need it as soon as possible. And everybody kind of wants it.

And it’s just, you know, we have a government busy doing other things. Now that

Sruli Fruchter: Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

Haviv Rettig Gur: You keep asking these questions. I don’t understand.

Sruli Fruchter: I have a sense you wouldn’t like this question.

Haviv Rettig Gur: What’s Zionism? I don’t know.

Sruli Fruchter: You tell me.

Haviv Rettig Gur: I don’t know. I don’t know what, what’s the purpose of Zionism? Jews had three options in the 20th century.

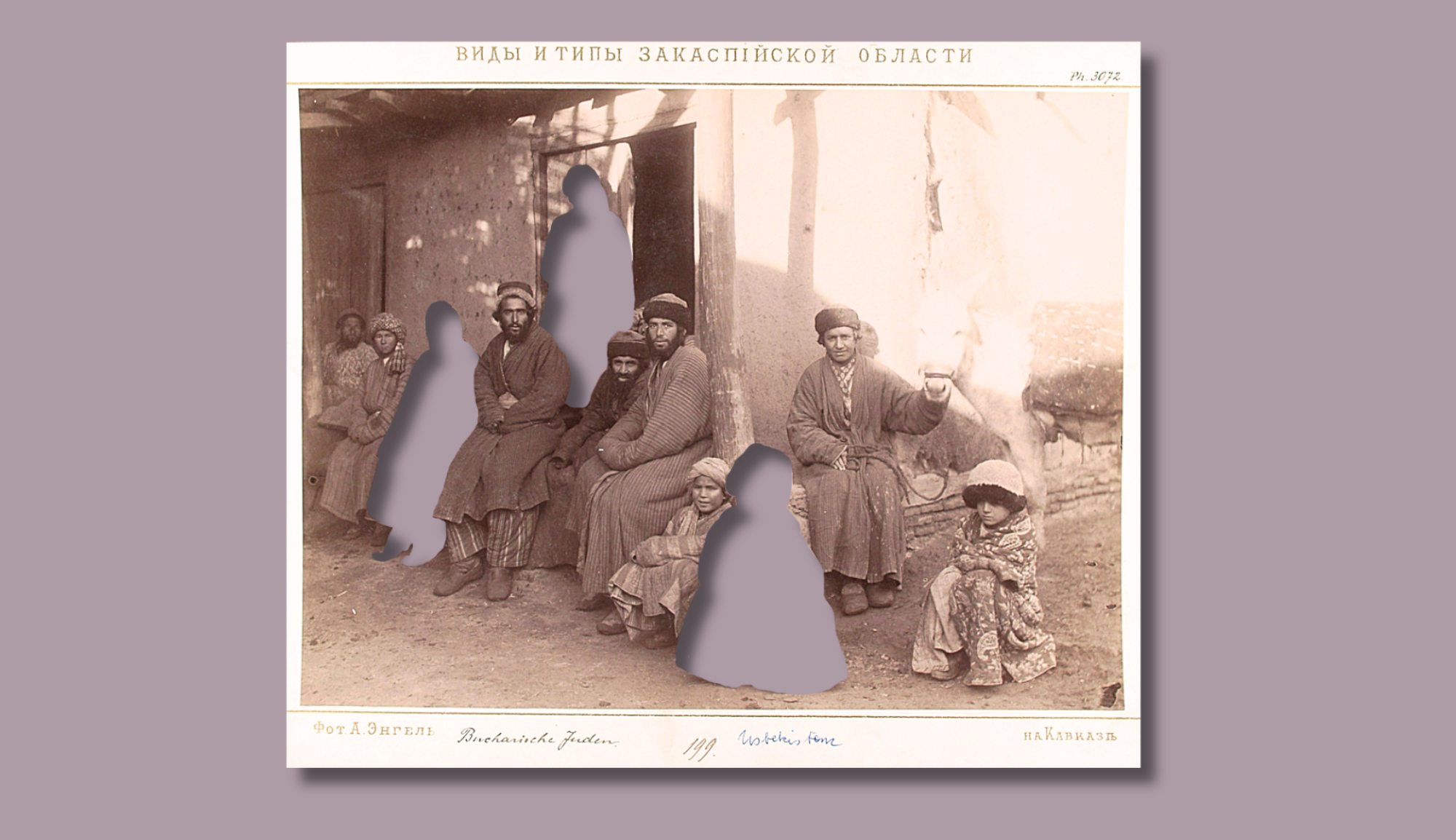

Learn English, learn Hebrew, or die. Sorry. Well, sorry to the Russian Jews and the French Jews, but statistically this holds. Jews who could not get into the English-speaking world, when the English-speaking world put up its quotas in the 20s and 30s, were rescued by Zionism and by no one else.

What’s the purpose of Zionism? Millions of living Jews who would otherwise not be living. What is its purpose now that they’re living? Stay alive. I don’t know. I don’t think that Zionism as, I’ll tell you why I hate that question.

I know exactly why I hate that question. I hate that question because out there in the world, when they look at us, they think of us and they’re taught to think of us by other Jews. They think of us as an ideological option. You could be a socialist, a communist, a liberal Democrat, a social Democrat.

What am I missing?

Sruli Fruchter: Probably a lot.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Ultra-Orthodox, Bundist. I don’t know what. You can be 17 different ideological options and Zionism is one of them.

And because it’s one of many ideological options for a safe person to choose as a life journey, it’s okay to also say, ew, yuck, that’s a bad one. Don’t pick that one. The people who think this way are profoundly ignorant people who don’t know their own story. The Jews who think this way, who don’t know their own story.

Non-Jews who think this way don’t know the Jew’s story, so they shouldn’t be emotionally invested in thinking this way because you shouldn’t be emotionally invested in the inner identities of other people whose life stories you don’t know, on account of how that’s a pretty good signal of bigotry. But Jews who think this way don’t know the Jewish story that produced Israel. Most Israelis are refugees. Most Israelis fled here.

Most Israelis had no other option. Their grandparents we’re talking about, not them, right? And so the question, what is the purpose of Zionism today, is a very silly question. It’s a little bit like asking, what is the purpose of medicine anymore? I mean, not a lot of people get polio. What’s the purpose of medicine? Zionism was a movement that produced many, many ideological elites, the religious Zionist vision that interpreted this whole vast flow of migrants and refugees, the socialist Zionists, the liberal Zionists, all these different kinds of Zionists, who are these intellectual elites that wrote books and thought about this vast social change, this vast movement of millions of people fleeing people.

But that’s not what Zionism is. Zionism, the thing that they all had in common, was the rescue project, was Herzl. There’s a catastrophe coming, and if we don’t organize for it, we’re going to die. That’s Zionism.

Is it still relevant? Yes. You know how I know? Not a single Jew lives in Iraq, and not a single Jew can live in Iraq. We still need Zionism. In America, they’re debating whether the Jews are so white that they’re bad, or maybe a little less white, so they have to be a little bit respected.

They’re still not good because they’re not non-white. People are still putting Jews into the position of playing cartoon characters in the moral cartoons running around in their own heads, and don’t experience that as their own bigotry. And the Jews still have to deal with it. And so we still need Zionism.

I’ll tell you what Zionism gives us. It’s a hack of history. When they love Jews, nobody has to talk about Zionism. Who cares about Zionism? I don’t care, you care, nobody cares.

And then when they hate Jews, suddenly there’s Zionism. They can go to, they can just move, they have where to go, that will accept them, embrace them, and fight a war to defend them. In other words, there are no bad endings anymore. A Jew living in Canada, either Canada is a place where a Jew can live happy and be Canadian and everyone accepts and they’re integrated and everything’s happy, in which case, beautiful, or Zionism kicks in.

Welcome to the Zionist hack of history. There are no bad endings anymore. And so yes, Zionism is still relevant. The fact that it’s so unbelievably successful that we can’t even imagine a situation in which we would need to build it into that catastrophic 20th century in which it was built, just proves how successful it is.

Sruli Fruchter: Seems like a pretty good question. You had a lot to say.

Haviv Rettig Gur: It was a good question. Questions we have to reframe are not bad questions.

Sruli Fruchter: Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Or ignorant? A lot of wonderful, decent, ignorant people. And some profoundly antisemitic ones. It depends, you know, if you genuinely don’t know that the Jews who actually built Israel had no other choice, then you may think they had another choice and wish they had chosen that. And then we can have this nuanced debate over whether you get to choose how other nations live or die.

But there was a cost to the founding of Israel. And the Arabs, the Palestinians in this land paid a great cost for it. Not so vast a cost, they paid a huge cost for the Arab response. Probably a greater cost, because it was the Arab world that didn’t let them found a state, not us, in that sense.

There were a thousand opportunities to draw a line in the sand when we were weak, and they didn’t take it. So you can have this debate, but that’s an interesting historical debate. But none of it really matters when you realize that a quarter of the IDF in 1948 was DPs who had nowhere else to go on earth and had been living in, you know, Buchenwald after the war for three more years because no one woul d take them in. And they’re a quarter of the IDF soldiers of 48.

So if your anti-Zionist argument is, I wish Israel had never been founded and these Jews were just dead like all the other Jews in the Eastern Hemisphere, huge numbers of, not all, obviously, then yeah, you’re an antisemite. If you think of Zionism as one option among 16 and imagine that all Jews could all move to China or something, or could have gone to New York, chose not to go to New York, they really should have gone to New York. We would have taken them in. That’s not quite antisemitism.

It’s just deep, profound ignorance.

Sruli Fruchter: Which question do you think we’re up to?

Haviv Rettig Gur: 12.

Sruli Fruchter: We’re halfway through.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Okay.

Sruli Fruchter: But we ask that to everyone. That’s not because it’s long. Some people have taken that as a signal. If we were long, I would tell you.

Is the IDF the world’s most moral army?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I don’t know. I have not measured the morality of armies. The IDF understands very clearly that profound immorality in war is detrimental to the war effort. Every IDF officer I’ve ever met is worried about their own morality.

Every soldier who makes every decision doesn’t want to walk away from that decision thinking they were bad, evil, immoral. I served for years in the IDF. I stood at checkpoints. I saw soldiers do bad things, steal cakes from a bakery truck going past, a Palestinian bakery truck.

And I saw another soldier report it. And I saw them fight. And worse things than that happen. Armies are big, complicated places.

300,000 soldiers were called up to the Gaza War, just reservists. You can’t call up 300,000 people without a few criminals among them, statistically. The Israeli army is an army. And it is an army that doesn’t want to think of itself as doing bad things.

And so it tries to do things the right way. It happens to be true that it is nearly always true that morality and professionalism go hand in hand. Whenever you’re in an army, you see a unit that does bad things. It usually is also the most incompetent unit around.

And it’s a unit that you need to get disciplined so that it can actually accomplish the mission as well. So I think the Israeli army on balance is quite a moral army. I think that from full military service in the infantry, including during Defensive Shield in the West Bank, when we walked into Palestinian towns and villages and cities. And I also think it’s an army that fails sometimes, obviously.

When I was in basic training, we had classes on Israeli war crimes. I have a friend who was in one of the branches of the US military, and he said that they also had combat soldiers, have classes on war crimes in the history of their own army, of their own branch. The Kafr Qasim Massacre, 1956, border patrol units, which is technically under the Israel police, but it’s functionally a military unit. They do four months infantry training.

And they hold borders and they do a lot of work in the West Bank as well, a lot of security work. And in 1956, there was a still military rule left over from the 48, 49 war on Israeli Arab towns, which would be lifted in the 60s. And there was a curfew in Kafr Qasim in 1956. And some agricultural workers didn’t know about the curfew, and they were coming home and the border patrol soldiers opened fire on them.

And that was a massacre that went all the way to the Israeli Supreme Court. And the Israeli military teaches new enlistees that Supreme Court decision. The idea is that even if the order is legal, it is illegal, because there are certain things that are very clearly illegal, even if technically it went through the right command chain. There was absolutely no sense.

Israel is a signatory on Fourth Geneva. In other words, the stipulations of the Geneva Conventions are Israeli law as well as international law. And so the Israeli army knows that it is an army, and that armies go to war and fight wars. And our enemies have dragged all wars with us into civilian populations as a force multiplier.

Our enemies aren’t troubled by this. Our enemies eagerly pursue the death of their own civilian populations, which I think was the most shocking thing for Israelis on October 7. October 7 itself, our failure, our collapse, our army’s collapse was the trauma, was the great horror. But the simple fact that Hamas planned the destruction of Gaza and then did something to ensure it happened and to give us basically, in our view, no choice is the shocking part.

The willingness to destroy Gaza in order to destroy us is a thing we cannot imagine because our government is not willing to destroy us to destroy the enemy. And so we have an army that is aware of the moral failings of its past and is also aware that it doesn’t want them in the future. It is a moral point. It is a point you see in every officer you meet and every soldier you meet.

They don’t want to think of themselves as bad. They do want to know how to do the right thing. They do need to still win. If the laws of moral war mean they can’t win, they will ignore those laws.

But if they can win with better, more moral actions, they will pursue them. And we have all these experts from West Point and places like that who tell us the Israeli army is instituted. By the way, you don’t even have to think the Israelis are good. They’ve instituted more measures for preventing civilian death while the enemy is pursuing civilian death as its fundamental strategy than any army in any battle in the world.

Sruli Fruchter: If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Well, first of all, in the audience, right? The case for Israel among Muslims in the Middle East is very different to the case for Israel in Paris or Denver, Colorado. But I don’t make the case for Israel. I would begin by not doing so. We do not stand before the world and ask to be.

I travel to Jewish communities to teach Jews their story because Jews who know their story are invincible. And they will already fight their local fights and debate their local debates, and they know how to do it. I don’t know how to. You have a TikTok account?

Sruli Fruchter: Personally, no.

Haviv Rettig Gur: No, I don’t either. Apparently, we’re losing 200 to one on TikTok. I don’t know how to do that. I don’t have an account, right? The college kid has the account.

I need to tell the college kid his story. And then he will take the war to TikTok. And so I don’t make the case for Israel. We are a nation.

Two and a half million school kids went to school this morning speaking Ivrit. I don’t even understand what anti-Israel means. It’s like being anti-Canada. Okay, you’re anti-Canada.

It makes you happy. I’m glad you have that happiness in your life. My kids are still going to go to school. I’m still going to speak the language I speak.

I’m still going to do what I do, right? I mean, we’re a civilization. We’re a society. We speak our own language. In other words, I don’t believe that we need to make the case for Israel.

There’s specific arguments. There’s this war being fought now on our story. And the Jews caught in that war, I feel for that. And I want to teach the Jews their history fast, because then they are invincible.

And by the way, nothing I tell Jews about their story, nothing about the refugee history of Israel exonerates Israel from some mistake or crime, right? You want to be left-wing? I promise you, you’ll learn everything I have to teach. You can still be left-wing. You want to be right-wing? Nothing I’m going to teach you is going to not make you right-wing anymore. But know your story.

And that’s the case for Israel.

Sruli Fruchter: Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army, even in the context of this war, be considered a valid form of love and patriotism?

Haviv Rettig Gur: No, God forbid. If you ever question, you should die.

Sruli Fruchter: That’ll be the tagline for the episode.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yes. Do not question or die. I mean, so obviously that, yeah. I know why you’re asking the question.

There are some silly people. I love these silly people, but they are silly, who may feel, not even think otherwise sometimes. But that’s so obviously, you know, not a thing. I would say it’s awfully hard to not question.

They’re a government. The best government you could possibly have is screwing up on half the things. My complaint is they’re screwing up on 75% of the things. You know, I’d forgive them if it was only 50%.

Yes, you really should. You should. Don’t give them a second to breathe. They’ll be better for it.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

Haviv Rettig Gur: It owes Palestinians answers. We need to destroy Hamas. Hamas sets the price. Here’s why we’re willing to do it.

Here’s why not just right-wing Israelis are willing to do it. Here’s why left-wing Israelis are willing to do it. Left-wing Israelis who yearn and hunger for a Palestinian state, for ending the occupation, are willing to destroy Hamas at whatever cost sets. Because they remember 1996.

Rabin is assassinated. Peres is running to keep the peace process running and advancing. Netanyahu has warned Israelis this will bring terrorists with guns into their midst. And a week before election day, there are two, maybe three, I forget exactly.

Folks don’t work hard. Look it up on Wikipedia. There’s suicide bombings in Jerusalem. And they tilt the election a tiny, tiny fraction of a bit away from the Oslo left, by the way, Hamas suicide bombings, by Hamas, to the critical right, to Netanyahu saying, guys, this is going to end badly.

And he wins that election, I think by 30,000 votes, the narrowest margin in the history of Israeli elections. Hamas pushed the left out of power in 1996. That’s not even, I mean, the right says this, and I’m not even accusing the right of winning because of Hamas. The right said, guys, this will end in terror.

There was terror. It’s like, we won this exactly for what we said we would, right? And then the Second Intifada.

Sruli Fruchter: Is that the kind of answer you think Palestinians want?

Haviv Rettig Gur: No, but it’s, I don’t, I mean, I don’t care what they want. I know what they need from me, about me.

If they’ve come to understand me, if they need to interpret me, if they need to try and figure me out so they can destroy me and defeat me, I have some things to say when they’re trying to learn about me. Here’s what you need to know, dear Palestinians. Hamas pushed the left out of power and delayed Oslo in ‘96. In 2000, in ‘87, at the beginning of the First Intifada, Israeli soldiers were literally running traffic in every Palestinian city.

13 years later, by 2000, there were no Israeli soldiers in any Palestinian city, town or village. And there was a PA, and two years earlier, the soldiers had pulled out massively from everywhere. And they were negotiating shared sovereignty on the Temple Mount at Camp David. And that’s when 140 suicide bombings began, driven quite, to a significant extent, Arafat had a big role, significant extent by Hamas.

Sruli Fruchter: What’s the particular criticism that you find that you’re identifying as leveled against Israel?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Until Hamas is gone, it will destroy everything anyone tries to do for Palestinians. There is no recovery for Gaza if Hamas isn’t removed. You cannot send $100 billion into Gaza

Sruli Fruchter: Is that a criticism of Israel or of Hamas?

Haviv Rettig Gur: It’s the criticism of Israel is after you understand that the defeat of Hamas unites Israelis, because not because Israelis don’t want the Palestinians to have a future.

The Israelis who desperately want the Palestinians to have a good future here want to destroy Hamas because in their experience, Hamas kept preventing that from happening. The day after Hamas is gone, assuming that’s possible, I happen to think it’s possible, I even happen to think it’s not that hard, but most people disagree with me. So maybe they’re right and I’m wrong. Israel owes the Palestinians big, big answers about a future, about self-determination.

They don’t elect the Israeli military governor of the West Bank, and that is not sustainable. There has to be an answer, and there are solutions, but the solutions begin with reconciliation. We used to think that you find the right border, you find the right policy, you find the right clever refugee formula. And we, Western, you know, diplomats used to think that if you can navigate between the range of the policy question, the reconciliation will solve itself.

It turns out, no, it won’t. Until you have the reconciliation, none of the policies will work. So the second Hamas is gone, frankly, the Palestinians start to win in the best sense of the term, because then they are actually able to engage the Israeli society, Israeli politics, and they actually have real needs, and we actually need to solve their problems.

Sruli Fruchter: So this is a good segue to the next question we had.

Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I don’t know. I don’t know about peace. I still think in the end we separate. I still think …

Sruli Fruchter: By separate, you’re referring to a two-state solution?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Some kind of two-state solution, yeah. And it might be a two-state solution heavily dependent on the Arab world. And in other words, some kind of a Palestinian-Jordanian confederation. It’s so silly to go into these kinds of ideas.

But if the Palestinian political elites can overcome a century of thinking about us as the arm of imperialism of various empires, and the colonialist French colonizers of Algeria, and all these different sort of visions that they have of us, as something essentially that can be peeled off of the land if only they’re violent and cruel enough. If they can overcome that, and they’ll overcome that because it’ll fail catastrophically. They won’t overcome that because we’ll convince them and it’ll be a polite sitting over coffee. But if they can overcome that, these ideological elites of Palestinian society, then all kinds of policy prescriptions become possible.

They become even easy. The problem is that there are still Palestinian elites that think they can win. And so it’s worth destroying everything on that altar of that victory. So yes, I am in that sense optimistic.

We’re humans, right? So we’re going to do everything possible other than the solution. And then when all of it fails, we’re going to finally get to the solution. But after it all fails, we will eventually get to the solution. A lot of people talk now in the West, these sort of very moral, very tormented people about a one state solution.

I think that’s adorable. It’s just, how could people who can’t trust each other enough to have two states, suddenly have one state? Why would the Jews after the 20th century give up their capacity to defend themselves? Which is what a one state solution is. Why would the Palestinians who will enter this one state massively, with a huge gap in economics and power, possibly trust the Jews? All the Palestinians know is that you can’t trust the Jews. The Jews are expansionist and all that, right? That’s their discourse about us.

It’s a very silly idea to reach the level of trust where you can separate, to reach the level of trust where you can live together. You’ve long ago passed the level of trust where you can separate much more easily. Live much happier, I think, separate than locked in together into this thing. Anyway, I think in the end we end up with two states.

Sruli Fruchter: What should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the war?

Haviv Rettig Gur: What’s my fantasy? What do you

Sruli Fruchter: think should happen? If

Haviv Rettig Gur: If I was God’s advisor?

Sruli Fruchter: Netanyahu just called us during the interview. He said, Haviv, I want you to—

Haviv Rettig Gur: I don’t think Netanyahu could pull it off. Let’s say Elijah the Prophet shows up and says, what do you think should happen? We’re stumped up here in heaven. First of all, I would have that Israeli chutzpah of telling heaven what to do, which of course, as a Jew, I’m perfectly comfortable with.

But I think that A, deradicalization, B, deradicalization, and C, deradicalization. Gaza has the world’s sympathy, profound sympathy. It deserves it. That sympathy will translate into infinite dollars.

If the Palestinians can piece together a political framework that isn’t Hamas, won’t destroy everything that would be built with those hundreds of billions of dollars over time. And it’s just at the most basic level, fundamentally competent. Israel doesn’t want a war with Gaza. Israel doesn’t need a war with Gaza.

Gaza could be everything that people talk about sort of flippantly, a shiny beacon of Singapore and all that stuff. It could be easily. The sympathy money is probably bigger than oil money at this point. But you have to have a way to absorb it.

At this moment, every dollar that the EU or the Germans or the Americans will spend on Gaza will be lost to Hamas. And so the future for Gaza is a deradicalized, de-Hamasized, massively supported, aided, you know, massive foreign development money. That if they can just have just the most fundamental competence, you know, Israel in its early days was weak and poor and corrupt and competent enough to build everything that would come in the future. I’m not saying they need to be, you know, start on day one as Norway.

But if they can start on day one as post, you know, Soviet Poland, then they will build something beautiful there. All of it depends on deradicalization. All of it depends on Hamas not ruling the place. And as long as it does, nothing will help.

You dump $100 billion there, it’ll look the same in 10 years.

Sruli Fruchter: Where do you read news about Israel?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Me? Original sources. Um, journalists have a lot of WhatsApp and Telegram lists where all of the political statements and press releases from the army and universities put out statements and institutions and NGOs and all that all comes flowing into your box. And I, you know, my newspaper has communication channels where, you know, I know what the military reporter is saying before it goes up, things like that.

And then you have literally original sources. Talk to leaders, politicians, analysts, experts. There are people I read for the grand sort of analysis. It’s not one.

There are conservatives, liberals.

Sruli Fruchter: Top three. Or your top 18.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah, you’re going to make me have, exactly.

I’m going to get calls. Why didn’t you mention me? Correct calls by good people. I would say whoever is on the unexpected side of the debate.

Sruli Fruchter: So to get you out of trouble, can I say who are the three people you’ve read today?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I mean, some of my really fundamental teachers on more than a single topic, right? If I’m dealing with judicial reform, there’s a bunch of lawyers that I talk to.

I mean, law professors and significant people. But basically, they’re just people who deal with law all day. But if you go beyond a single issue, my dad. My dad is a PhD, former rabbi, former lawyer, former many things, and avid reader of books in history and things like that.

And I have, you know, a lot of the stuff I talk about now, the history of the Jews and the story of the Jews, comes from wonderful books of history, who are my teachers, more than anything else. If I was to recommend a couple, it would be Götz Aly. G-O-T-Z is his first name. He’s a German historian.

Aly, A-L-Y, is his last name. He wrote a book called Europe Against the Jews. Recently, I think it’s fairly new. I think it’s in the last few years, but it’s available on Amazon.

I believe it’s even in an audiobook. And it’s the history of Europe emptying of its Jews up to the Holocaust, of the millions set to fleeing, of the laws passed in Romania and Poland, taking away rights to university access. And in other words, the Holocaust, he argues, was this horrific crescendo of a 60-year process that’s far larger than Germany itself. He doesn’t exonerate the Nazis of anything, anything.

He clearly lays out the horrors. Without the Nazi planning, without the Nazi extermination. Because he’s a German non-Jewish historian writing about this, so he does have to also say that. But he also explains it and demonstrates it beautifully.

But he also explains that Europe made itself uninhabitable to Jews, literally. And the Jews fled. And if you understand that, you can’t stay anti-Zionist. Your anti-Zionism becomes clearly silly.

Because there’s literally no other choice. So, and many others, many other books like it. There’s a wonderful book in English and Hebrew, definitely no audiobook version, though, called Israel and the Family of Nations. It’s a book written by Professor Alexander Yakobson of Hebrew University and Professor Amnon Rubinstein, who is the former Meretz minister of education, former dean of the Tel Aviv University Law School.

The man who wrote in 1992, the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty, Israel’s if there is a Bill of Rights in Israel. And it’s very minimal, but it’s all he could get through. But that is it. And these two gentlemen put together a book that is probably the finest defense of Zionism in the last 40, 50 years.

And in Hebrew, it’s available as a retail book, regular price in a bookstore. In English, it was classified by the British publisher as academic. And so I think it costs $140. I hope that that academic pricing isn’t an attempt to silence the book.

This was, I don’t know, 20 years ago, 15 years ago. But yeah, it’s an astonishing work where it delves into, I actually hope people don’t read it because some double digit percentage of what I say is from that book. And so I’ll be much less impressive. People will know the deep answers.

These are two scholars who, Alex is a historian, and Amnon was a great legal scholar and constitutional scholar. And from those two directions, they tackle left wing academic elite, sort of sensemaking elite discourses in the West. And they go beyond English speaking. They go to French, they go to German.

And so they can tackle the colonialism question at a very high level that’s happening on campus, right? If you’re a Jewish college student at Columbia and the head of your department, I don’t know which department, I’m not focusing on a specific person, but if the head of the department rails against Zionism being colonialism, you as this, you know, B.A. student, you know, freshman or sophomore, are going to have an awfully hard time there saying, no, right? And because there’s all that stature. And so these guys just go right for the throat and give tremendous history and give it really in a very clear, concise, calm way. And the footnotes, the footnotes are wonderful. And you will dive as deep as you want and you will swim as far as you want.

And you will come out really knowledgeable about your own story. So that book is an absolute must on every bookshelf in the Jewish world.

Sruli Fruchter: Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum? And do you have friends on the other side?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I’m a Gur Chassid, so UTJ. That was meant in jest, although I understand they’re very good people.

It’s a good one. Where do I identify? I like good people and I’m disgusted by public servants who don’t know they work for me, who think I work for them. That doesn’t narrow it down much.

Sruli Fruchter: I assumed you wouldn’t want to say precisely.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah, but no, but it’s really important for me to say, Meretz and Labor, their new joint party, are led by some extraordinary people who will demonstrably charge into gunfire for every other person in this country. And that is true of 80% of the front bench of Likud. And so we have extraordinary people across the political spectrum and a politics that are petty and corrupted by all kinds of phenomenon that are not unique to Israel. They’re happening across the democratic world.

But nevertheless, when people ask me who to vote for, I really tell them that there are many options and they should be comfortable voting because these are good people.

Sruli Fruchter: The question is less focused on who you’d vote for and more where you identify politically on the spectrum. If you’re not comfortable answering, I would try and push once more, but I don’t think that’ll get me anywhere.

Haviv Rettig Gur: I’m comfortable voting almost everywhere. Almost everywhere.

Sruli Fruchter: No, not comfortable voting.

Haviv Rettig Gur: The people I want to get a beer with are Shas. I’m not comfortable voting for Shas because I don’t like the state religious system.

Sruli Fruchter: I think that’s as good as I’m going to get.

Haviv Rettig Gur: But on a lot of other issues, Shas has been a shining example that I wish other parties would follow. And so Shas, which is very far from me on sort of culture, I find myself as comfortable around them as around people closer to me culturally. So yeah, I don’t…

By the way, in the Arab world, political world in Israel, I find myself much more comfortable around conservative Muslims than around, you know, urban, secular, you know, socialist elites, which are two different political factions in the Arab community. So I don’t know. I drink beer with conservative religious people and I urge people to vote their conscience comfortably on most, most political factions.

Sruli Fruchter: And on the religious spectrum.

You’re Haredi, secular, Daty Leumi? Somewhere in between? Modern Orthodox Jewish day school?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah. Yes. Good question.

Super boring question. Really, I’m so boring. I cannot even express how boring I am. There is a God because…

Sruli Fruchter: I’m talking more religious identity, not necessarily like the beliefs themselves. But if there is a religious identity that you feel represents you, wonderful. If not, then I think I’ve learned after 16 questions, I’m not going to get much further than where you’ll let me go.

Haviv Rettig Gur: I don’t do identities all that well.

I don’t do identities all that well. And loyalty of that kind bothers me. I think with a little less loyalty to political tribes, we’d have better politicians and healthier politics. And so, yeah, I don’t…

When I drive down the Ayalon in central Tel Aviv and see a billboard of a woman in her underwear, I feel awfully Haredi. And my five-year-old daughter shouldn’t have to live in a world where she’s constantly exposed to women’s advertising worthy bodies. And I spent a great part of my 20s in the Jewish thought department at Hebrew University trying to figure out what I think about God. So not a yeshiva, but a university.

But nevertheless, I kind of treated it as a yeshiva. So I don’t know. Do you identify with a specific religious faction?

Sruli Fruchter: You’ll find out on my 18 questions interview.

Haviv Rettig Gur: So like, for example, if I go into the Hasidic world, I love the Kotzker Rebbe, because the Kotzker Rebbe never built around himself …

He never built around himself, you know, a court. A court, an institutional, right? And there is a tradition in my family, I cannot prove, I don’t know if it’s true, but that we are the direct descendants of the Maggid of Mezeritch, the chief student of the Baal Shem Tov at the founding of Hasidism. I cannot prove it. And the one time I told it to…

Sruli Fruchter: If we question that, we have to question everything else you

Haviv Rettig Gur: said. One time I told that once to a wonderful Haredi rabbi, who I had a chavruta with when I was a teenager, because my dad wanted to make sure his sons, we were three boys, his sons grew up knowing a little bit of Gemara and knowing how to read a page of Gemara. And so I said, oh, you know, I don’t know what a cocky 17 year old, we’re the direct eighth generation from the Maggid of Mezeritch. And he says to me, you know, the best, you know why, Yichus, right?

Lineage is like a carrot. The best part’s underground. So that was his very correct answer. But the Kotzker Rebbe was someone who said, all that stuff is not, right.

You have these deep, profound, broken existence, and we have a duty in this world, and we are that conscious piece of it that brings things together. And that’s what it’s about. And all these courts and all of these tribes and all of these, I have trouble with tribes. I have a tribe.

I have a tribe. I will, it turns out, I have discovered about myself that I will live and also die. Dying is easy. Living is hard for my people and to defend my people and to, you know, slap my people on the cheek when they think they’re being silly and wrong.

But I have a tribe, but that’s the tribe. I don’t have a tribe within the Jews. Yeah.

For our last question, do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish people?

Haviv Rettig Gur: 99% hope and the 1% glimmer of fear.

Not hope, not even hope, not even hope. Look around. This is the Jewish people sitting here in the heart of Jerusalem. That’s not hope.

When you have a kid who’s already got three gold medals at the Olympics, you don’t hope he does well in gymnastics. It’s not hope. It’s certainty and pride and comfort and safety and a sureness about the future. And the 1% glimmer of fear, you know, they say one small candle, I’m real chassidish today, dispels much darkness.

Sruli Fruchter: You’re a Gur Hasid, you said.

I’m not actually, but you know, yeah. Um, and one tiny little drop of poison will ruin a whole big bottle of wine. But it’s the same fear that was always there.

Chazal teach us that what brought down the last Jewish kingdom was not the great and immense and unstoppable power of the Roman empire that conquered everything it saw. That was technically what did it, what actually did it, Chazal say, was us and our internal schisms and our stupidity and folly and silliness and vindictiveness and a politics of civil war. And that’s the one thing that will always fail us. That was the only real weakness we have.

And I see Israelis struggling against these centrifugal forces, pulling them apart. And whenever the chips are down, nobody asks questions. And so I, my frustration, my anger at this leadership, not for the left-wing reasons, I don’t think that this leadership is literally betraying us because they’re politicking away, you know, around the war and letting the hostages die on purpose. But they are willing to purposefully and constantly produce a politics that makes half the people think that way because it’s a good political strategy.

And that’s the betrayal. And that’s our only weakness. And so I don’t mind if the right wins or if the left wins. I mind that people who set us against each other lose.