Yonatan Adler: What Archeologists Find

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Dr. Yonatan Adler about the intersection of halacha and archaeology.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Dr. Yonatan Adler about the intersection of halacha and archaeology.

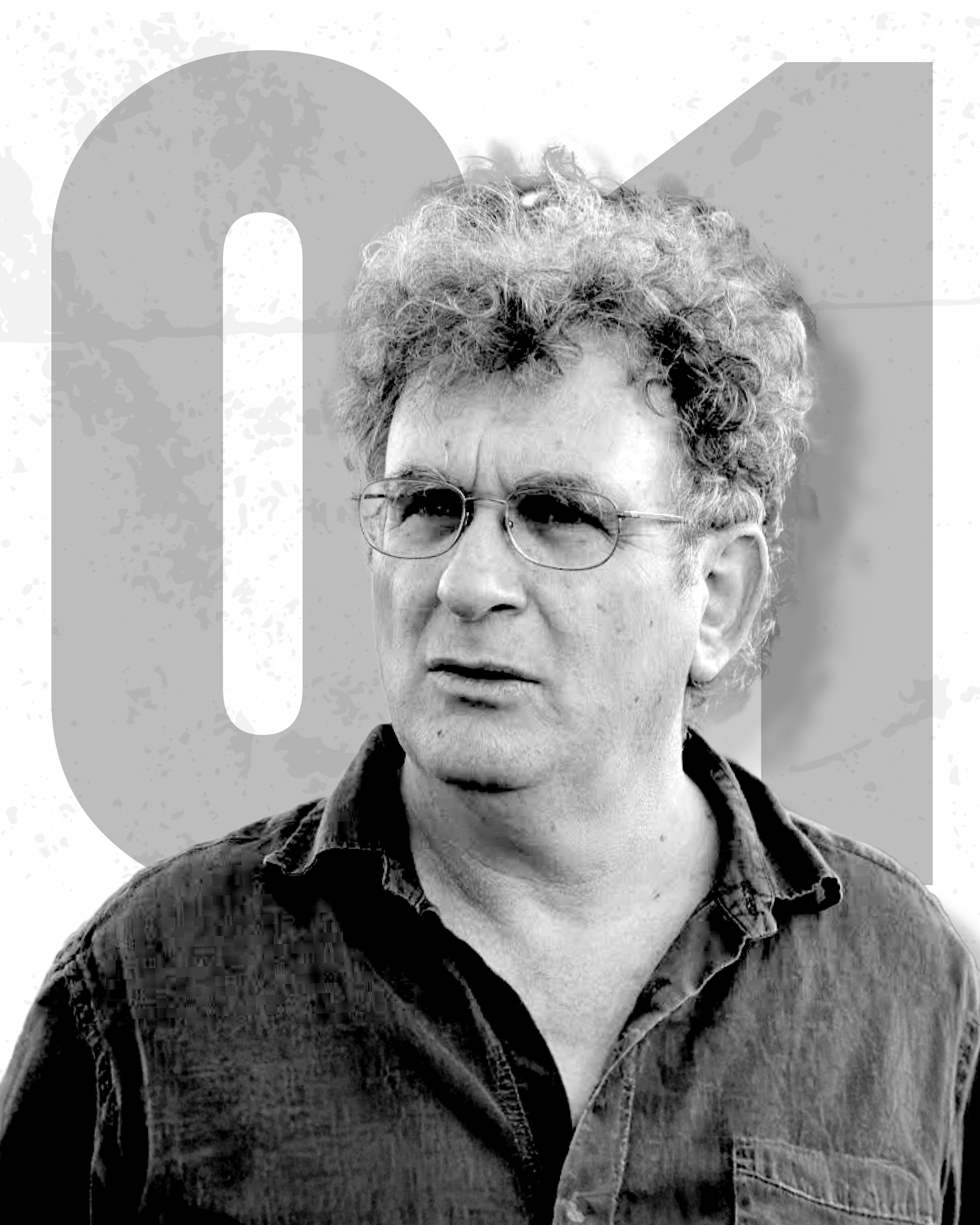

Yonatan Adler is a professor of archaeology at Ariel University in Samaria where he teaches about halacha in early Judaism as we see it through the lens of archeology.

- Why do we view the past in light of the present and not the present in light of the past?

- What does archeology tell us about the origins of the Jewish People?

- Did ancient everyday Jews keep the Torah?

Tune in to hear a conversation on the blueprint of creation, the invention of the term ‘Judaism’, and more.

Interview begins at 23:15

References:

“Hazon Ish on Textual Criticism and Halakhah” by Tzvi A. Yehuda

18Forty – “Andrew Solomon: Far From the Tree”

“Hazon Ish on Textual Criticism and Halakhah – A Rejoinder” by Shnayer Leiman

“The Role of Manuscripts in Halakhic Decision-Making: Hazon Ish, his Precursors and Contemporaries” by Moshe Bleich

Iggrot HaRav Kook – Letter #423 by Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook

The Origins of Judaism by Yonatan Adler

Judaism: The Genealogy of a Modern Notion by Daniel Boyarin

“This is Water” by David Foster Wallace

Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism by Menahem Stern

Josephus: The Complete Works by Flavius Josephus

The Jewish War by Flavius Josephus

Drashos Beis Yishai – Essay #23 by Shlomo Fisher

18Forty – “Tova Ganzel: The Judaism of the Prophets & the People”

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring the origins of Judaism. Ooh, sounds spooky. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18Forty.org, that’s 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org. You can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.

My introduction to the field of archeology did not go so well. I believe it was on a trip with my family, and my father organized one of these tour guides that knows all of the… They just know all of Israel in every detail. And maybe it was a function of my age, more likely it was a function of my maturity, most likely it was a function of my absolute ignorance of anything related to Tanach at the time, because I remember he would take us to these cliffs and he would say, “Oh, this mountain range is the exact same mountain range as described in the book of Tzephaniah and Micha“. And I’d be like, “Okay, first off, I’ve never heard of those books of Tanach, so I think you’re making this up. Second of all, I’m not sure I care.”

I wasn’t into it. It did not go well. And I remember mid-tour I was like, “I think it’s time to go home.” And I don’t think we made it to the end of it. I was just not engaged. I was not interested. It was not speaking my language. Again, I knew so little about Tanach, and he’s showing me all these things, the, “Oh, this is in the chapter described in Malachim, the Book of Kings,” et cetera, et cetera. And I was like, “I never read this stuff, so I really don’t know what you’re describing or what you’re talking about.”

I have come to love the reality of Israel a great deal more. I think a part of that is from these really charming clips that my rebbe, Rav Ari Waxman sometimes shares on Twitter on Erev Shabbos where he will hold up a grape from Israel and explain some pasuk in Tanach. And maybe it’s just like his enthusiasm, my love for him, the joy, but I like the reality now. I’m much more into it than I was back then. But I think that initial introduction to archeology didn’t stay that way because there was a discussion related to archeology that absolutely fascinated me that I was exposed to in high school. My grandfather died when I was in 12th grade, and one of the treasures that I inherited from him was the entire collection of the journal Tradition. Tradition Journal, which is run by our friends Jeffrey Saks and the board over there.

They do absolutely phenomenal work and all of Traditions’ archives, of course, are available at traditiononline.org/archives. So when my grandfather passed away, Rabbi Moshe Bekritsky, I inherited the entire Tradition archives. And let me just say, I absolutely love the work of Tradition. We use so much of it informing the work that we do here. But I do want to say one thing. If you go back to the very beginning, the scholarship is absolutely excellent throughout, but I want to spend a moment talking about the graphic design of the covers. Dare I say, and I want to say it now for those listening. You heard it here first: I think the old design was the best. I think the first design of Tradition, these block letters, very colorful, was the best design.

Bring back these really popping colors to Traditions, bring back the soft pastels. We’re not talking enough about graphic design of our scholarly publications enough within our community, but we don’t ignore it here in 18Forty, and I’m happy to wax poetic about the quality of our book covers, our journal design, and if you really push me, we could talk about my favorite fonts, but that’s not for right now.

There was a discussion that I found in this collection that I inherited from my grandfather. There’s an article that came out in the summer of 1980, volume 18 issue number two that was published by somebody named Professor Tzvi A. Yehuda. It doesn’t have a biography in the article, but it’s clear from the article that this was a student of the Chazon Ish, of course one of the great leaders of halacha, really a radical thinker in a lot of ways if you look at the way that he understands the development of halacha. And he spends a great deal of time really on these meta issues, why halacha developed the way that it did and really says incredibly creative, radical, fascinating ideas and there’s nobody more qualified to speak on these issues of course, than the Chazon Ish that was fairly more in depth and his writings is not always so accessible.

But this Professor Tzvi A. Yehuda was clearly a student of the Chazon Ish and the Chazon Ish did say some radical things as it related to the development of halacha. First and foremost, he does suggest that there’s some divine providence in the way that our tradition has been formulated. What manuscripts, what information came to us. There’s a providence in the way that this tradition that we have that we call our mesorah came about and even sometimes that came at the expense of some manuscripts that were unavailable to previous generations. But in this article, which is entitled ‘Hazon Ish on Textual Criticism and Halakhah’, again, this is in the summer 1980, volume 18 issue number two in Tradition journal, he writes as follows: “Here is a stunning example I heard from Chazon Ish, assuming that an old sefer Torah from a very remote past will be found, let us say of Rashi, Rabbi Akiva, or any other great authority of antiquity or for the sake of argument even of Moshe Rabbeinu himself and that we will detect textual variance, distinguishing it from the current mesoretic texts…”

In parenthesis, he writes in spelling, malei and chaser, kri and ksiv, these different ways in which we write out the words; form of letters, division of parshiot, et cetera, all of which is not only possible but even expected because of both the fallibility and the dignity of the mortal scribes, which are neither angels nor robots. What are we going to do?” It’s an absolutely fascinating question. It’s a tantalizing question. Anytime that you go on an archeological dig and you’re wondering, they’ll pull out a pair of tefillin that may look differently than our own. They’ll discover mikvaos that may have been built differently than our own. They’ll find some piece of information from the past that make us question our present. How should we factor that in? This is not a new question. 18Forty is not raising this of course for the first time, and this isn’t the first time that it was dealt with, but the Chazon Ish did spend time dealing with this and this is what Professor Yehuda writes, “Halacha dictates, said the Chazon Ish, that we do not correct our sefarim according to the old sefer, but vice versa.”

“The old sefer Torah, even if it were written by the greatest authority, must be considered pasul as long as it does not conform to ours. In order for it to become kosher, it must be amended and adjusted to comply with the text of the contemporary sefarim, according to the regulations of the most recent halacha. It seems strange. We view the past in light of the present and not the present in light of the past. Why?” What a great sentence which relates squarely to everything that we’re discussing in this series. We view the past in light of the present and not the present in light of the past. When deciding halacha, what we care about is the present tradition in front of us. We’re not trying to find the oldest tradition and we’re not trying to find the work that dates back the farthest, in the present is how we reconstruct the past.

It’s that first model that we discussed in the introduction to the series. “And the question is why the halachicconception of correctness with regard to the Torah text, like any other item in the purview of halacha,” I’m reading directly from the article, “is based on the rule of majority not antiquity. This is the general halachicway of gauging reality and properness. It is horizontal, not vertical.” What a fascinating sentence. “It is horizontal, not vertical.” This resonates a great deal with me even though as we’ll see, there’s a great deal of pushback in the way that he characterizes the opinion of the Chazon Ish. But I love that idea. It is horizontal, it is not vertical. We’re not trying to go back and find the oldest. We’re trying to see what was preserved in the present. It reminds me of the distinction that Professor Andrew Solomon made in our series on intergenerational divergence in his book that we discussed in our interview “Far From the Tree” about the difference between horizontal versus vertical identity.

Does our identity stem back where we go vertically to the person before us, before us? Or do we have a horizontal identity to the people beside us? And I think both of these exist in a way when it comes to our halachic identities, but what he’s emphasizing over here that our halachic identity is not just a vertical identity, it’s not just what goes back the farthest. Oh, I have this sefer Torah that’s 3000 years old. I have a pair of tefillin that’s 2,500 years old and we go based on that. No, we really need to factor in and a major part of our halachic identity, it’s not the vertical identity, it’s our horizontal identity, what was preserved by the collective mesorah that exists now in the present, the Knesses Yisrael. What have we embodied over all of these generations? The story of course does not end here.

Somebody responded to this article, I believe it was his first time ever writing in Tradition Journal. Somebody who went on to write dozens of more times. A name that I hope our listeners are familiar with, I think he may be one of the greatest living Jewish scholars. Just really his command of Jewish scholarship knows no bounds. Also an absolutely fascinating individual, one who I hope though I doubt would ever accept the invitation, but a man can dream… It would be an absolute pleasure and privilege to have Professor Shnayer Leiman on 18Forty. And in his first article, I believe this is number one, this is the first time he ever contributed, he’s gone on to write many, many other times of course. But the first time he ever published I believe, was in response to this article from Professor Yehuda and he wrote an article again, ‘Hazon Ish on Textual Criticism and Halakhah’, a rejoinder in the winter 1981. This is volume 19 issue number four.

And he begins the article as follows, and I love the beginning. Professor Leiman writes, “What is meritorious about Tzvi A. Yehuda’s essay entitled ‘Hazon Ish on Textual Criticism and Halakhah’ is that it clearly sets forth questions that all intelligent Jews should ask regarding Torah and textual criticism. Can archeological discovery influence halacha if per chance archeologist discovered a copy of the Torah written by Moshe Rebbeinu himself, would halacha require Torah scribes to correct our Torah scrolls in light of the original? Should we take seriously the variant readings of the text of the Talmud and the numerous Gaonicinterpretations of Talmud texts that were lost for centuries only to be rediscovered in the Cairo Geniza in this century? Should these readings and interpretations be induced or ignored by rabbis concerned with the halachic consequences of classical Jewish texts?” It’s a fantastic introduction because it validates everything that we’re looking at, everything that we’re examining in this series.

And I love that Professor Leiman says quite emphatically that all intelligent Jews should ask regarding Torah and textual criticism. These are good questions. These aren’t heretical questions that are reserved for-These are good questions to really understand how our history and how our memory function with one another. What happens when the history contradicts, so to speak, the living memory and the question that he asked black on white, can archeological discovery influence halacha? He rejects the stance of Professor Yehuda that we wouldn’t factor in if we were to find the sefer Torah so to speak, written by Moshe Rabbeinu and that it would have no bearing on our tradition. He actually poses an absolutely fascinating thought experiment to undermine the logic of Professor Yehuda who argued… Professor Yehuda argued that it wouldn’t have any bearing because we decide based on the majority, what’s known in Talmudic parlance as the rov, the majority.

And he says that makes no sense. This is what Professor Leiman writes: “Let us suppose for heuristic purposes that a demented Jewish scribe decided to write thousands of Torah scrolls establishing new readings at a new majority.” I love that. A, I love the fact that he uses the word heuristic, which we know is one of my favorite words that I overuse constantly. But he says it here. Professor Leiman gives us his stamp of approval for using the word heuristic. I also love the thought experiment, “a demented Jewish scribe.” We need more thought experiments that involve demented Jewish scribes. There actually are stories about evil demented Jewish scribes. There’s a famous story with the Noda b’Yehuda that I believe ends with someone’s hands getting cut off. Spoiler alert, it’s not the Noda b’Yehuda‘s hands, but that’s a story for a different time.

Right now in this thought experiment we’re saying a demented Jewish scribe writing thousands of Torahscrolls and they’re all printed wrong deliberately. Would the new majority supplant the old one? Needless to say, Professor Leiman writes, it would not. Majority rule, rov in halacha governs only in instances of doubt,like there’s a safek, there’s a doubt. Where certainty reigns, majority rule plays no role. Indeed, tradition has it. And I love this story, there’s a famous story that Rabbi Jonathan Eibschutz was once asked by a gentile sage, happens to be one of his major fields of interest of Professor Leiman is in the life of Rav Yonasan Eibschutz as he’s more commonly known. In this article he calls him Rabbi Jonathan Eibschutz, who actually did interact quite a bit with Christian scholars at his time. So it could be this is actually a true story and Rav Yonasan Eibschutz was asked by a gentile sage, the Torah dictates that one must follow the majority as it says in Exodus 23:2. If so, should not all Jews convert to Christianity since Christians clearly outnumber Jews?

And Rav Yonasan Eibschutz replied that majority rule prevails only in doubtful matters. Jews, however are quite certain about the truthfulness of their religious beliefs. Professor Leiman is skeptical. He says we would absolutely factor in a sefer Torah that was written by Moshe Rabbeinu if we knew definitively that it was, of course that would have bearing on the sefer Torah that we have today. How could we outrightly dismiss it? The issue is, he says, that we need some skepticism to know, is it in fact belonging to Moshe Rabbeinu number one? And when we get a new manuscript, we have to know is there reason to believe that this is in fact more correct? Professor Leiman pushes back that he may be giving too much importance to this notion that the Chazon Ish talks about a divine providence through history, that that means that any accident of history is decidedly a part of our sanctified tradition.

He quotes a great story and he writes at the end, he says, “It would appear to be the better side of wisdom to admit that not all accidents of history are the will of God.” He quotes a story of thousands of Bibles printed in England in 1632, were printed with the following verse, “Thou shalt commit adultery.” “No one claimed that the printer’s error was the will of God,” Professor Leiman writes, “the King’s printers were fined 3000 pounds sterling for their literary indiscretion. My point here is not that the emandation of biblical text under ordinary circumstances is desirable or even permissible, but rather that a theory of textual determinism that mechanically elevates human error to divine fiat creates more problems than it solves.” We can’t just flat out say he seems to be arguing that anything preserved through history must be this way. There’s some things that are legitimate accidents and I would absolutely love one of those 1632 Bibles that say “Thou shalt commit adultery.” That’s a real demented printer over there. That’s fascinating.

But be it that as it may, we have to engage to some degree with definitive historical truth, though we can’t automatically assume just because something is older that means it’s necessarily more correct. That’s not really how history works. It’s not necessarily how archeology works. It’s certainly not how preserving a tradition necessarily works. There was one more article. Didn’t end over there, began with Professor Yehuda and had a follow up from Professor Leiman. There was another article from a writer who was written very infrequently in Tradition and his name is Rabbi Moshe Bleich. I believe this is the son of the quite famous Rabbi JD Bleich whose collection of articles in Tradition about halacha, contemporary halachic problems are absolute classics. He was writing these broad overviews of contemporary halachic issues before all the search engines even existed. I believe this Rabbi Bleich is his son.

At the time, his bio says that he’s a member of the editorial staff of Machon Mishnas Rabbi Aaron, studies at the Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood, and is the spiritual leader of Congregation Machzikei Torah. There’s another Moshe Bleich, it could just be an updated bio, who I believe works in social work. I’m not sure if it’s the same person, but he wrote a response to this whole discussion about the Chazon Ish‘s approach to textual emendation, how the past affects the present tradition. And his article, which was published in the winter 1993 issue a few years later, volume 27, issue number two, his article’s called ‘The Role of Manuscripts in Halakhic Decision-Making: Hazon Ish, his Precursors and Contemporaries’. And he shows that this notion of attributing divine providence to our mesorah, to the canon that we have preserved even to exclude certain manuscripts that were not included is a fairly old tradition. Chazon Ish did not make this up, but he provides a lot more nuance into this discussion and you should really check out this article. It’s absolutely fantastic. I’m not going to read the whole thing. Maybe I’ll read the last paragraph just to know how he concludes and basically sums it up. One really fascinating bonus to this article by Rabbi Moshe Bleich is that there’s an end note that’s only tangentially related, but it deals with an absolutely fascinating question that has nothing to do with this series or what we’re talking about today. But I always love the endnote to this and the question that he deals with is whether or not non-Jews get a reward, get schar, get reward merit for performing mitzvahs. Fascinating question. If you ever thought of stopping a non-Jew on the street and asking that they put on tefillin today, make sure to read the endnote to that article, which is absolutely fantastic.

But he basically ends his very detailed discussion about how history factors in halacha with the following: “Nevertheless,” he writes, “for halachic purposes, it is the consensus of contemporary authorities that inordinate weight not be given to newly published material. Even earlier authorities who gave a relatively high degree of credence to newly discovered manuscripts did so within a limited context. Accordingly, formulation of novel halachic positions and adjudication of halachic disputes on the basis of such sources can be undertaken only with extreme caution.” And to me, this is acknowledging that our tradition is really an integration of both a vertical and a horizontal identity.

The vertical identity that stretches all the way up, the oldest, the most antiquated definitely has a role in this but we also need to factor in our horizontal identity, what was preserved and the divine providence that goes into that preservation. What was thought over, what was sacrificed for, what ideas did we preserve in our tradition through the ages also is a major part of the corpus of our tradition of course, that horizontal identity in correspondence to what we normally just think of as a vertical identity.

And this measured response to archeology is paralleled in some ways in the writing of Rav Kook. Rav Kook, who was the first chief rabbi of Israel, was quite aware of the seriousness in which archeological discovery could pose or questions that could arise both halachic and theological that could arise out of archeological discovery and so much of the early founding of Israel where these jaw-dropping discoveries related to Israel. He has a very short letter, even though we discussed this on several different occasions, about whether or not we should factor in archeological discoveries related to what were considered walled cities, which is a major halachic factor in deciding when you should read the Megillah on Purim. We don’t need to go into those details here, but there was an archeological discovery that basically changed our prior conception of what was and was not a walled city, which would’ve changed when they should be reading the Megillah, what day they should be reading the Megillah on Purim.

And Rav Kook responded regarding archeological finds. I’ll read it in Hebrew and then of course I’ll translate. So “Ki kol ha’chochma hazot“, this entire field of knowledge, “shel chakirat madda Eretz Yisrael” of investigating archeological of the knowledge of the land of Israel itself. “Mileeah hi rak hashharos,” is filled with approximations. “She’omnam reuim heim l’chiba, v’kavod hachokrim” that nonetheless we should definitely love and give honor to these scientists,”v’hadorshin b’zeh” and those who really expound and investigate these areas. “mi’tzad chibas ha’kodesh,” just from our land of the love of Israel. “aval sof kol sof“, at the end of the day, he writes, “ei efshar likvoa masmores” we can’t like hang a nail and decide all of our tradition just because of an archeological find and I think some of this healthy, I don’t even want to use the word skepticism, but healthy understanding of how our present tradition actually arises… It’s not trying to find the oldest thing possible. It factors in the interpretations of the generations as filtered through thousands of years. It is not just a vertical identity, it is also a horizontal identity.

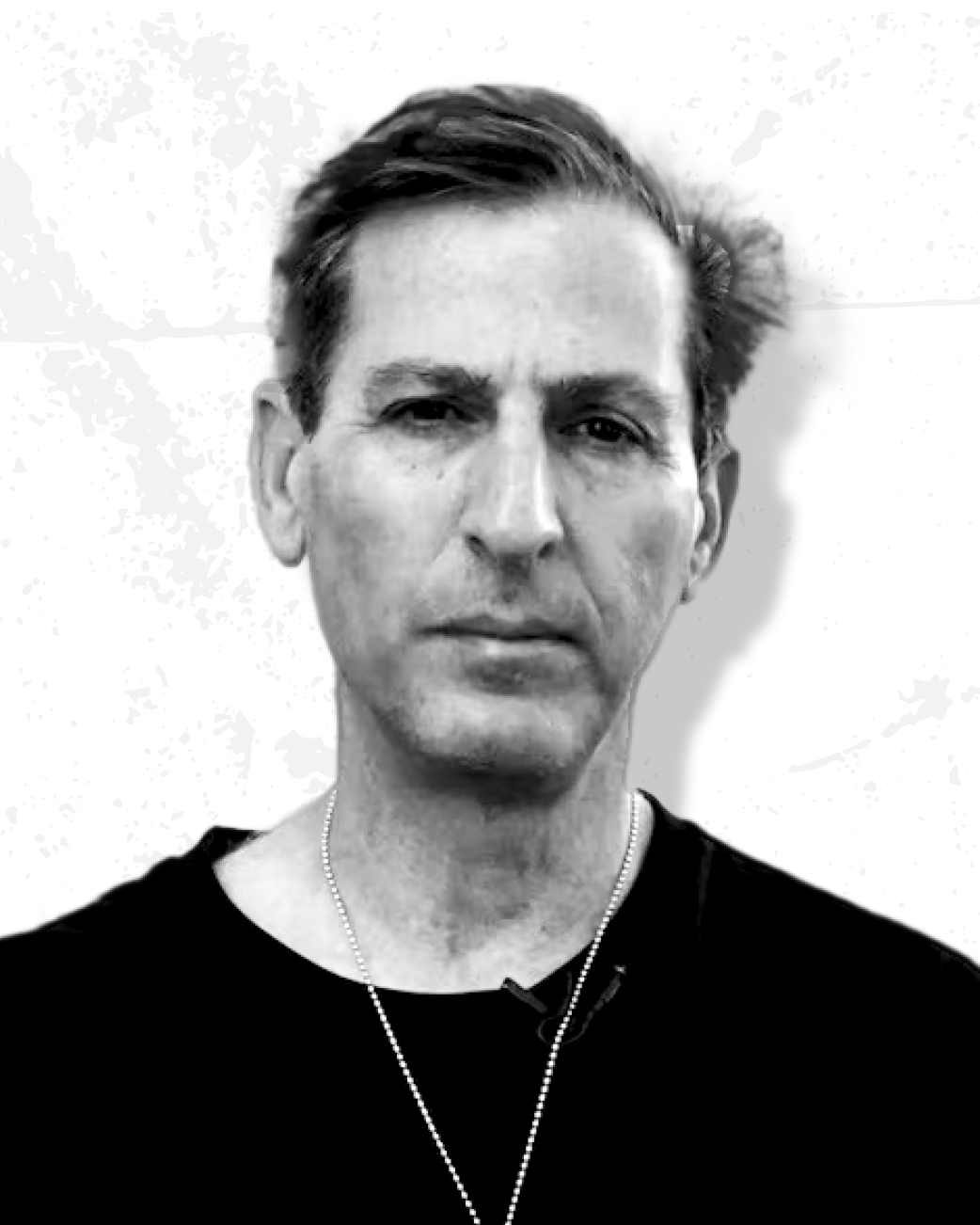

And I think some of this framing is necessary to understand our conversation with Dr. Yonatan Adler. Dr. Yonatan Adler is an archeologist in Israel and speaks the language of archeology. And we tried to stay very focused in our interview on what archeology does and does not tell us. And I think it was absolutely fascinating our discussion about his forthcoming book, The Origins of Judaism. I did not yet read it and you can tell in the interview, this was recorded before the Queen of England unfortunately passed away as you’ll listen to in the interview. But it’s an absolutely fascinating take to understand what exactly do archeologists do, what does archeological information tell us about the development of Judaism? And it’s an absolutely fascinating lens to better understand what is buried, so to speak, underneath all the rubble of our memory. What can this aspect or this area of Jewish history tell us?

Without further ado, my conversation with Professor Yonatan Adler.

It is my distinct pleasure to introduce a scholar whose book caught my attention being published by Yale called The Origins of Judaism. It is my absolute pleasure to speak today with Dr. Yonatan Adler.

Yonatan Adler:

Thank you for having me.

David Bashevkin:

Really, really exciting to have you. You’re going to correct me 1,001 times. You are an archeologist in Israel, correct?

Yonatan Adler:

Correct. I’m an archeologist in Israel. I’m an associate professor at Ariel University and my area of interest is early Judaism, so I look at Judaism and how it developed, how it originated, how it emerged, how it developed over time, specifically through the lens of archeology. So I focus on the material aspects of ancient Judaism, but I of course don’t ignore the texts that also shed light on early Judaism. So I look both at texts and the material finds, which we unearth through archeology.

David Bashevkin:

When I think archeology, honestly my mind goes to Jurassic Park, of people finding dinosaur bones and trying to figure out what period they lived in. When you think of a historian, you think of somebody who’s poring through old texts, you’re obviously studying a period that predated both the printed word and is quite a couple years after dinosaurs. So I’m curious, what exactly does an archeologist do? What is the evidence? Are you in the field with a little pick axe and one of those cool hats? What exactly are you doing and what is the evidence at the data point, so to speak, that you even look at to develop your ideas?

Yonatan Adler:

Okay, so first of all, I need to bust a myth here.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Yonatan Adler:

Archeologists do not do dinosaurs. Okay? So I teach this in my first class on archeology. Dinosaurs predate human beings by a long time and archeology actually focuses on human beings, human activities. So if it doesn’t involve humans, archeologists are not interested. I tell my students if an archeologist is digging and finds a dinosaur, an entire skeleton of a dinosaur, we don’t deal with it. We call a paleontologist and if he doesn’t come then we’ll just throw out the dinosaur bones. Because archeologists are not interested in dinosaurs.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. A lot of our listeners who are planning on careers in archeology may just have changed their mind, but I appreciate that-

Yonatan Adler:

Okay.

David Bashevkin:

… myth. So what do in fact an archeologist do?

Yonatan Adler:

Okay, so our interest is in the past both archeologists and historians are interested in the past. The difference, and I think it’s a bit of an unfortunate distinction that we make between history and archeology… Historians deal with texts. So anything that’s written down in ancient times or before today, let’s say, a historian will be interested in the text for what it can teach us about the human past.

Archeologists, their interest is on material remain. So things that you can touch, things that you can bang your fist on and what that can teach us about the human past. So our interest is the human past and the question is what tools do we use to uncover information about the human past? Archeologists can go further back in time than historians because writing was invented only at a certain period of time. Only about what is, it depends where we are on planet Earth, but let’s say if we’re talking about in the Middle East, we’re going back say about 4,000 years, you know, 5,000 years at the most, archeologists can go back much further in time because we have remains that humans have left over from before there was writing.

Archeologists also deal with historical periods, periods of time when we have texts, but the texts only give us a very, very small window on the ancient past. And archeology gives us a different window. I like to give the metaphor of how we would love to be able to look on the past as a vast panorama, but unfortunately the wall of time stands in between us and we have here and there in this wall that’s blocking our vista of the past, here and there we have these little slits in the wall that we can peer through and see little snippets of the past. You know, one little slit will be a historical document, another slit will be a different historical document. Another slit will be pottery that we find and stone vessels that we find and buildings that we find. And it’s unfortunate that there are some people that only look through the slits of the texts and other people look through only the slits of the material find.

I think what we need to do optimally is to look through all of the slits that we have in this wall of time in order to get the best picture that we have. At the end of the day, we’re not going to get that panoramic view that we would love to have, but if we take advantage of all the different little slits that we have in the wall, we’ll get a semblance of a picture of what the past was. So what I do, I work with both of these things. I work both with the texts and with the archeological finds in order to get the best picture that we can possibly have.

David Bashevkin:

I absolutely love that imagery and the wall of time is frustrating for a lot of people because especially now where we preserve so much in the digital space that it’s warped our understanding of how the past used to be preserved and we want to have that certainty about what the past was and look like. And you do kind of have to squint quite a great deal, but there is so much that we can learn.

And I wanted to begin actually with a question that predates your focus within your book, which obviously we’re going to get to, and that is the role of archeology specifically in Israel, where archeology in other countries, I get the impression, I don’t want to call it a hobby, it’s nice, it’s not as politically interwoven in the landscape as it is in Israel. I believe Israel, I’m sure other countries have one, but there’s a great deal of political interest in archeology in Israel, particularly discussing the existence of Jews in Israel. Do you work specifically with the government in discussing kind of how to present or understand the existence of Jews within the land of Israel?

Yonatan Adler:

Okay, so you’re a hundred percent right that historically archeology has been interwoven with politics. Good archeologists are doing science, so good archeologists are archeologists that try not to allow their own personal ideologies, whether they’re political or religious or any other ideologies affect the questions that they ask or the answers that they take out of their work. As all scientists should be trying to be as objective as possible in their work. We’re all humans and we all have our subjectivities, we all have our biases, but as scientists, we should be doing our utmost in order to squash those ideologies and those biases when we’re doing our work, right? We’re allowed to have our beliefs and our political beliefs, our religious beliefs and so on and so forth. But they shouldn’t be allowed to affect our work. I think that’s just simple science. That’s what science is all about.

Have archeologists always been successful in that? No, I can give you plenty of examples where archeologists not only in Israel by the way, so you have all over the place archeology being misused towards political ends. I’ll just give you one example: I read a few years ago in a Swedish newspaper, they were writing about how Sweden is very open to immigration from the Muslim world and there were archeologists that discovered a very, very early evidence of Muslims in Sweden going back more than a thousand years. And this was touted towards political ends, let’s say. So it’s not only in Israel that we have, we have it a lot in Israel because we have a lot of politics in Israel, but certainly any good archeologists, and I would say today almost all of the archeologists that are working in the field are driven by science and not by politics.

David Bashevkin:

Your work deals with a fascinating distinction and I wanted to parse apart both of them and talk about them separately. Your book is called The Origins of Judaism, which is about the religion which is distinct from a different question of the origin of the Jews, meaning the people as a distinct civilization within Israel. I want to get to both and I’m wondering if we could start with I think what first emerged, which is the distinct people, the Jewish People. What does archeology, if anything, tell us about the origins of the Jewish People, so to speak? When do we find, particularly in Israel, obviously that’s what I’m censoring around… What does it tell us that maybe what does it not tell us?

Yonatan Adler:

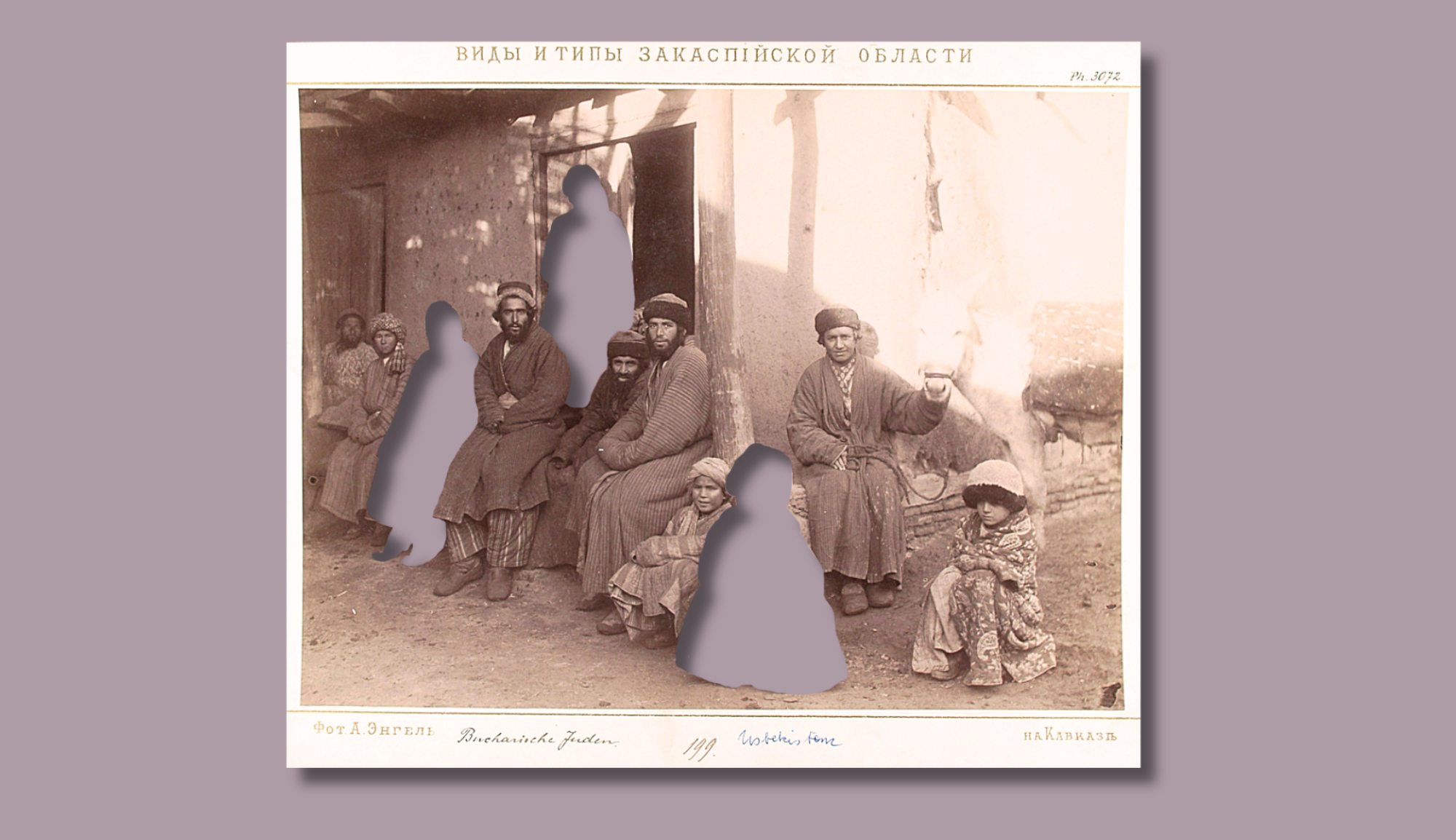

So that’s a very complicated question and I would say it’s even a bit of a minefield in terms of the question. I’ll just put out a few of the complications and I don’t want to get into too many details because this is actually not my field, but I will get into a little bit of the details. First of all, the questions of terminology terms. I’m not sure if you mentioned Israel as a people; when do we have evidence of a people we can call Israel? When do we have evidence of a people we can call Judah or Judean or Jews? Is there a distinction between Judean and Jews? And all of these are debates that we have in scholarship today. So if we wanted to know from when we have a people that call themselves Israel or a people that call themselves Judah, we would have to look at texts, ancient texts, but we would have to look at texts that we have from the ancient past.

But archeologists actually are able to look for a distinct group that we might have in a certain part of the country, let’s say the hill country of modern day Israel, and ask questions, like is this the beginning of something we might call Israel or Judah? Is this maybe a proto-Israel or something of the sort? All of these are very complicated questions. They also involve questions and definitions, but scholarship has been working on this for quite some time. But I would say in terms of the names, so the earliest texts that we have as far as I know that refers to Judeans comes from Assyria, from the time of Sanchereb where we have Chizkiyahu, Hezekiah the king is called a Judean in Acadian. And then we have from that point and onward the biblical texts and we have Greek texts that speak of Ioudaios, which is the Greek term for Judeans. Afterwards we have Latin, the same name appears in Latin and so on and so forth.

So we have this term already appearing, let’s say at the end of the eighth century before the common era. And, yeah, as a people, we know that this people existed quite early. The question that interests me in my work and in my book isn’t the origin of the Judeans, my interest is in the origins of what I call Judaism. And I try to avoid the term religion. I don’t like the term, I think it’s a modern term.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

We don’t have a term for religion in Hebrew, in biblical Hebrew there’s no term for religion, and there’s not even a term for Judaism in Hebrew until the modern era.

David Bashevkin:

So interesting that you mentioned that. We don’t have a term for Judaism until the modern era like yahadutis a very modern term. You don’t see that-

Yonatan Adler:

Modern term. Daniel Boyarin published a book recently, I think in 2019 called, I think it’s called The Genealogy of a Modern Notion. And he basically shows a fascinating point that he makes that there never was a term for Judaism prior to the modern era in any of the languages that the Jews spoke. There’s no term for Judaism to the modern era. So he takes that in a bit of a postmodern direction that if there’s no term for it, then the thing didn’t exist. And I don’t agree with that idea. I think a good example would be the term cisgender which is a word which is-

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

… comes up very much these days.

So I was born way before the term cisgender was ever coined, and I identify as cisgender. That means that I identify as the same gender as I was born into or as I was identified as when I was born. It’s basically the opposite of transgender.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Yonatan Adler:

So the question is, when I was a child and there wasn’t a term cisgender, does that mean that I wasn’t cisgender?

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Yonatan Adler:

Well, on a certain level of analysis, yeah, but it’s not a particularly interesting level of analysis. I’ve always been cisgender. The fact that there wasn’t a term for it doesn’t mean it didn’t exist. I think it’s the same thing with Judaism. Judaism existed, we didn’t have a term for it, I think because it just permeated every fiber of the fabric of our life that you didn’t need a term for it. It was just this is what Jewish life was. You didn’t need a term Judaism. And that’s why we don’t find any term like it.

David Bashevkin:

It reminds me of the great story that David Foster Wallace told at his commencement address, I think in Canyon State College, where there are two fish that are swimming next to each other and one fish turns to the other fish and says, “How’s the water today?” And the other fish turns him and says-

Yonatan Adler:

What’s water?

David Bashevkin:

… yeah, “What the heck is water?”

Yonatan Adler:

Yeah, exactly.

David Bashevkin:

Sometimes you have something that really just envelops your whole existence. It’s the one term that you don’t necessarily have a word for it, but please continue. What does it mean that you’re exploring the origins of Judaism?

Yonatan Adler:

So I use the term Judaism to mean the Jewish way of life governed by Torah law. So for most of our history, the Jewish way of life has been characterized by strict adherence to the laws of the Torah. And that’s governed everything we do from the time we wake up in the morning until we go to sleep at night from cradle to grave. And I can give myriad examples of all the things that affect the life of a Jew. And historically that’s how it’s been until the modern era, until things changed greatly, let’s say in the 19th century with reform and secularization in general. And even there you still have Judaism.

David Bashevkin:

But for most of history, starting… You give me a day from the first century CE, Jewish life was synonymous with a ritual observance that enveloped every aspect of somebody’s daily life.

Yonatan Adler:

We’ll get to the when it begins.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Yonatan Adler:

That’s the question of the book. But for hundreds of years this has been the situation. And we’re talking about things like diet, what we eat, what we don’t eat, what we wear, and what we don’t wear. The holidays that we follow, the blessings that we say, the prayers that we say, what time we say them. Purity laws, laws relating to marriage and conjugal life. Just about every aspect of life has rules that govern what you’re allowed to do, what you’re not allowed to do, prohibitions and practices. I think anyone who has any connection to Judaism knows about this. And of course it doesn’t mean that everyone agreed all the time about the details, but in general, this is what characterized Jewish life: adherence to the laws of the Torah.

So I use, there’s not a good word for this thing, this Jewish way of life governed by Torah law. I chose the word Judaism and I could defend why I chose the word but I think it’s a good key holder for this thing that interests me. It’s the thing that interests me. It’s not the word. I’m not interested in the definition of Judaism. My interest is in this thing. And particularly my interest is in the question from when does this exist? From when do we have evidence for the masses of Jew, right? Your regular everyday Jews as a society, knowing that there’s such a thing called the Torah regarding this Torah as authoritative and observing the laws of the Torah in their everyday lives. The question is, when does this begin?

David Bashevkin:

Why do you make a distinction? And I’m curious because it seems like you’re emphasizing it deliberately between the masses and you know, what could be termed. I don’t know if that’s in response to a minority, to the elite, to scholars. When you emphasize the adoption of the law by the masses or ritual observance, let’s call it, by the masses, that’s in contrast to what?

Yonatan Adler:

Excellent question. So yes, I’m emphasizing the masses. I’m emphasizing regular ordinary people. I’m emphasizing society. The reason is because oftentimes we look at ancient texts which talk about the Torah, right? Torat Moshe, which were written by, I would call them the Judean or Jewish literati. These are intellectuals who are highly literate, highly intelligent, who wrote ancient texts like the biblical text. And these are people who are not representative of regular everyday people, or not necessarily representative of regular everyday people. And it’s fully possible that you had a very small number of these intellectuals who knew of the notion of a Torah and regarded this Torah as authoritative and may have even been observing the laws of the Torah. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that your regular everyday people knew about, or that society at large knew about the Torah and were keeping the laws of the Torah.

So it’s a good question from when do we have the Torah? Right? That’s not a question which interests… It is a question which interests me, but not in my book. I’m not asking the question from when do we have the Torah? I’m asking the question from when do the Jewish people know about the Torah and from when do the Jewish people as a people, as a society regard the laws of the Torah as authoritative and are observant? So yes, my interest is specifically in the masses, in the regular everyday people. To put it in a bit of a different way, my interest is not in intellectual history. My interest is in social history. So I’m interested in Jewish society at large.

David Bashevkin:

Fascinating. And I think that’s why it’s so important to make it clear because you’re not saying that what you termed the social history of this adoption is the first evidence we have of the Jewish people or even the existence of this idea. But when did this become synonymous in this kind of mass social movement? So maybe you can begin with when do we know for sure that these became synonymous in your eyes, and what’s the evidence that you have that you call upon to say, this is when we for sure see that on the mass level ritual observance and early Judaism were synonymous with one another.

Yonatan Adler:

Okay. So maybe I’ll start off by describing the methodology that I go about in the book.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

Basically what I do is I take a period of time exactly as you said, from which we know, from which we have lots of evidence that this thing I’m calling Judaism existed. The first century of the common era is exactly such a time. So the first century, meaning beginning in the year one of the common era until the year 100, let’s say 99 of the common era, is a period of time when we happen to have lots of textual evidence and archeological evidence, which indicate that regular everyday Judeans were keeping the laws of the Torah and strictly keeping the laws of the Torah.

I’ll give you a couple of examples: Shabbat. Okay? The Jewish Sabbath is mentioned by both Jewish writers and non-Jewish writers as something which just about everyone was keeping. And the dietary laws, so both Jewish writers and non-Jewish writers are writing about the fact that Jews don’t eat pig.

David Bashevkin:

Can you give me some examples? Like who’s a non-Jewish writer who’s reporting on the shabbos and how are they describing it? That sounds fascinating.

Yonatan Adler:

There is a three volume set put out by the late Menahem Stern, a scholar of ancient history called ‘Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism’, and it’s a fascinating set of books, thick books, where he collates all of the ancient Greek and Latin authors that ever mention anything about Jews and Judaism or the land of Israel or anything like that.

David Bashevkin:

Wow.

Yonatan Adler:

And if you go through these volumes, you find one after another, these non-Jewish writers are mentioning things. Oftentimes they were wrong. So oftentimes they mixed up Shabbat and Yom Kippur. They thought that Shabbat was a day of fasting.

David Bashevkin:

Uh-huh. Has this been translated? Could you mention the name of the book because it sounds fascinating. I’ve heard of Menahem Stern, he was killed, I believe, right?

Yonatan Adler:

Correct.

David Bashevkin:

And he was murdered during the Intifada, but what’s the name of this book and is it in English?

Yonatan Adler:

Yeah, it’s in English. He brings both the original Greek and Latin and then translates it into English. So it’s very, very readable. “Greek and Latin authors on Jews and Judaism.”

David Bashevkin:

It sounds fascinating.

Yonatan Adler:

It’s fascinating. The first time I saw it, I bought it right away and I’ve been using it ever since. It’s a great set of standards for historians of ancient Judaism.

In any event, so we have these ancient writers, like I said, both Jews and non-Jews that are writing about this. And it’s not only that they’re mentioning that there is this thing called Shabbat. They’re describing society, they’re describing how Jews keep these laws.

David Bashevkin:

Are there any charming descriptions? Not to get too specific.

Yonatan Adler:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

I’m just curious. Some of these early descriptions, did any of them jump out at you or that you remember?

Yonatan Adler:

Yes. I’ll give you a very charming one. So there was one, I’m forgetting who this is ascribed to. There’s one ancient Roman historian who writes about Herod, right? So Herod, who lived at the end of the first century before the common era, that Herod was of course a Jewish king. And Herod was also a very… He was a horrible king, he killed everyone in his family and everyone that was close. So this Roman author quipped that it’s better to be Herod’s pig than to be his son. That’s how he writes it. Meaning that if you’re his pig, you know that Herod isn’t going to slaughter you to eat you.

David Bashevkin:

It’s not kosher.

Yonatan Adler:

But if you’re his son, chances are, he’s going to kill you. And it’s actually a play on words because in the Greek, the term pig and son are very similar.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, that’s very sweet. Minus the-

Yonatan Adler:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

… fact that he murdered his own family.

We’ll leave it that.

Yonatan Adler:

But the point is that even Herod, this evil king was known to have kept the dietary laws and we can go through practice and prohibition after practice and prohibition. I’ll give you a couple of archeological examples.

David Bashevkin:

Please.

Yonatan Adler:

So for example, we have a large number of tefillin that were discovered in the Judean Desert. And I have a project on that. I’m working on analyzing the tefillin right now. We have mezuzot from the Judean Desert.

David Bashevkin:

And what year approximately are the tefillin and mezuzot popping up?

Yonatan Adler:

So right now I’m talking about the first century.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Yonatan Adler:

The first century of the common era. Just to get an understanding, when I say the first century, I mean we’re going back 2000 years and to gain perspective, the second temple was destroyed in the year 70. So towards the end of the century,

David Bashevkin:

It’s contemporaneous with the Second Temple. Wow.

Yonatan Adler:

Right. So we have a standing temple throughout most of the century. One of the important pieces of data that we have, or one of the important sources that we have actually for this Judaism, is actually the New Testament because of course the New Testament, and particularly the first books of the New Testament, which are called the Gospels, they relate the life or the supposed stories about the life of a Jew who lived in Galilee in the first century. Of course, Jesus, he was a Jew-

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Yonatan Adler:

… and all of his followers were Jews and all of them kept the Torah. Right? So we have all kinds of stories about Shabbat and about discussions about exactly what you’re allowed to do on Shabbat, what you’re not allowed to do on Shabbat, of purity. We have all kinds of discussions about issues relating to purity. Nobody is ever saying, don’t keep these laws for Jews. Jesus never said it. None of his followers ever said that Jews don’t need to be keeping the laws of the Torah. So Torah observance permeates all of these texts.

And I started to talk about archeology. So we have literally hundreds of immersion pools, which today we would call mikvaot, which were being used by Jews on a daily basis. Basically every family had access to their own immersion pool. At the same time, we also have stone vessels, which are being used by Jews because they were regarded as impervious to ritual impurity. So people that were keeping the purity rules in their day-to-day lives were very careful. If they had pottery, they would’ve broken the pottery. And stone-

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Yonatan Adler:

… was considered impervious to ritual impurities. So we have this phenomenon of Jews in the first century that were using stone vessels as both storage vessels and tableware.

David Bashevkin:

I need to ask you, I’m sorry to jump in.

Yonatan Adler:

Okay.

David Bashevkin:

… in, and obviously we haven’t gotten to the full scope of your work yet, but I’m curious, you are fairly knowledgeable in halacha. I am curious, the mikvaos that we found, the tefillin that we found, were they what we would nowadays consider a kosher mikvah? And were the tefillin that were found, did they have any semblance to the tefillin that we wear now? Does this kind of resolve the famous dispute between Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam? I’m sure that’s the question that everybody’s asking right away.

Yonatan Adler:

It’s the question everyone asks me. We could actually do a podcast on each and every one of these topics. I teach a course called Archeology and Halacha Aleph, and Archeology and Halacha Bet, two semesters.

David Bashevkin:

Wow. Okay. We’re not going to be able to cover everything.

Yonatan Adler:

We’re not going to be able to cover everything. And-

David Bashevkin:

You don’t like short answers, you don’t want to give me the quick answer. I feel bad pigeonholing you.

Yonatan Adler:

I can give you a quick answer in terms of the mikvaot and the tefillin So the mikvaot, I wouldn’t know if the mikvah was kosher, because I don’t know if people were pouring in mayim sheuvim drawn water or not.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. Okay.

Yonatan Adler:

There’s no way to steer that archeologically and in terms terms of the tefillin, so that I can give you a bit of a better answer. So some of the tefillin that we have are exactly like the tefillin that we wear today in terms of the content.

David Bashevkin:

Mm-hmm.

Yonatan Adler:

But in terms of some other things, not just, for example, this is breaking news because this is something that I’ve just discovered in recent months. But doing an analysis on the skins that were being written on. I’m not going to be able to get into details here, but Chazal have their own, the ancient rabbis have their own take on exactly what part of the skin should be used for tefillin, what part of the skin should be used for mezuzah, so on and so forth. So the ancient tefillin that we have fit very well with that. Modern day tefillin, not so much. But that’s the story in and of itself. And-

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Yonatan Adler:

… like I said, you can invite me for another talk on tefillin.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, for another time, and I’m going to keep the tefillin I have now. Nobody panic. We’ll get to that later. Keep your tefillin people, don’t panic. I don’t know if you could buy the ancient tefillin that he had for sale. Something tells me they’re a little pricier than the ones that you get in your local Judaica store. But let’s continue.

So you have this period where it is quite apparent through the archeological record that the Jewish people living in Israel at the time, that’s the geographic area.

Yonatan Adler:

And in the diaspora.

David Bashevkin:

And in the diaspora. Give me examples in the diaspora. I’m thinking, you’re mentioning tefillin, you’re mentioning mikvah. What did we find in the diaspora?

Yonatan Adler:

Okay. So we actually don’t have yet archeological evidence for observance of Torah outside of the land of Israel. I wouldn’t make too much of that. It could be simply a matter of not being able to identify where we have Jews living in the diaspora. But we do have texts which talk about Jews in places like Alexandria, places like Asia Minor, Greece, Rome, Syria. We do have texts. We have authors like Philo of Alexandria that describe-

David Bashevkin:

Mm-hmm.

Yonatan Adler:

… Jewish way of life in Egypt. Josephus writes about Jewish communities throughout the Roman world, and the New Testament also writes about, we have descriptions of the Jewish way of life, and the Torah seems to have been something which characterized the Jewish way of life everywhere. So everywhere that there were Jews that we have evidence, Torah observance seems to have been ubiquitous.

Again, I want to stress that doesn’t mean there weren’t people here and there that weren’t breaking the law. There were, Josephus, for example, writes that if a Jew living in Jerusalem ate something that was forbidden, he would have to run away to the Samaritans.

David Bashevkin:

Huh.

Yonatan Adler:

Which in indicates that first of all, there were people here and there that would break the rules, which can only be expected.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

But it also imitates that there was such social sanction that they would have to run away if they did.

David Bashevkin:

Not much has changed.

Yonatan Adler:

Well, no, today, if you’re-

David Bashevkin:

You got to find another shul, you might not have go to another universe, but you got to at least go to the shuldown the block if the-

Yonatan Adler:

Today there are many secular Jews that don’t necessarily abide to the laws of kashrut.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. A secular Jew does not need to flee the-

Yonatan Adler:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

… community. Even if you live among religious Jews, that has changed.

Yonatan Adler:

Right. So the point is, there was no such thing as a secular Jew in the first century. It didn’t exist, but the notion didn’t exist. The notion of a religious Jew didn’t exist because, and then we get back to your fish in the water. Everyone was keeping the laws of the Torah. That was just what it meant to be a Jew in the first century.

David Bashevkin:

Mm-hmm.

Yonatan Adler:

So getting back to my methodology from the first century of the common era period, when we know that we have this thing called Judaism, I’m going backwards in time to see how far backwards in time do we still have evidence for this thing that I’m calling Judaism? Do we have evidence for it in the first century before the common era? Do we have evidence for this in the second century before the common era, in the third century, in the fourth century, in the fifth century?

How far back can we go and still find evidence, whether textural or archeological, which indicates that regular everyday people were keeping the laws of the Torah, they knew about the laws of the Torah and were keeping the laws of the Torah. That’s what I do in this book. And basically I have a chapter for each of the different categories. So I have a chapter on dietary laws. I have a chapter on the purity laws. I have a chapter on figural art. So in the first century, Jews universally refrain from depicting humans or animals and their art in deference to the second commandment, “lo taasei lecha pesel v’chol temunah“, you shall not make a graven image.

David Bashevkin:

And we really see them refraining from this?

Yonatan Adler:

Absolutely. There’s no doubt about it. We have a large amount of art, mosaics and frescos and stucco walls and ceilings and coins. So we have coins that are being minted by Jews in Jerusalem where you do not have any depictions of humans or animals. And this really stands out on the coins because even today on coins, coins that are minted in monarchies, you always have a depiction of the king or the queen.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, correct. I was going to say the president or a early politician.

Yonatan Adler:

Right. But in monarchies, but like in England, you’ll always have for now the Queen, right?

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

After meah v’esrim, it’ll be the king, presumably. And you have this throughout the world, you always have the monarch on the coin.

David Bashevkin:

She should live and be well.

Yonatan Adler:

She should live and be well, indeed. My grandmother in another month from now is going to be turning 100.

David Bashevkin:

K’neina hara.

Yonatan Adler:

She’s British.

David Bashevkin:

I could see you had a certain reverence for the queen.

Yonatan Adler:

So she should be getting a letter from the queen wishing her a happy birthday for her hundredth birthday.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. Should be good and gezunt.

Yonatan Adler:

My point is that, and this is going back to ancient times, ancient kings as well always had their face on the coins. When we get to the Jewish kings, so we get to the Jewish kings, Hasmonean rulers and kings. Herod, Herod’s sons, we never have their face in the coin. What do we have instead? We have a long text, which is describing the Jewish rulers.

So for example, the first of the Jewish rulers to mint a coin was first of the Hasmonean rulers to mint a coin was John Hyrcanus, Yochanan of Hyrcanus. Minted a coin which said John Hyrcanus, the high priest and the Council of the Jews. Right? This long, long text, which to my mind is a virtual portrait, it’s not a real portrait, because that you’re not allowed to put on the coin. It’s a virtual portrait, which you’re allowed to do. It’s text, it’s words, and that you have within a frame that you would normally reserve for the portrait of the ruler. The fact that we don’t have that, instead we have this long text is very, very clear indication that these early Jews are avoiding any kind of artistic depiction of animals or humans. And then we also have the texts like Josephus did talk about that say very clearly that Jews are not allowed to have depictions of animals or humans.

David Bashevkin:

Fascinating. What a fascinating chapter. So continue with the methodology and as you go backwards.

Yonatan Adler:

Okay. So then I’m looking at all these things. I also have a chapter on tefillin and mezuzot. I have a chapter on miscellaneous practices like Shabbat, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Pesach and also menorah. The seven branch menorah that mitzvah, it’s a commandment in the Torah that one has to have a seven branched menorah in the Temple. What evidence do we have for such a thing? Do we have, for example, evidence of the menorah being depicted in Jewish art? How far back does that go?

David Bashevkin:

Mm-hmm. Not of course the menorah of Chanukah, which is-

Yonatan Adler:

No, no, no. No, seven branch-

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Yonatan Adler:

… golden lamp that needs to be in the Temple.

David Bashevkin:

Uh-huh. What is the most curious… A lot of these are the big ones… You have kosher, you have Shabbos, tefillin. What is the most curious, like almost peripheral practice that you were surprised to have these early appearances of? Like obviously this wouldn’t exist. You have like an upsherin, which is a much more-

Yonatan Adler:

Oh.

David Bashevkin:

… that’s obviously a joke. That’s a contemporary practice where people wait three years that we don’t have this in my family, but a cute, I’m curious if there are any cute observances that you’re like, oh wow, that you were surprised to see how old they were.

Yonatan Adler:

So I’m not actually not particularly interested in cute observance. I’m sure there were. I’m interested in Torah. So if it says it in the Torah, I’m interested to know were people keeping this.

David Bashevkin:

Yes. Okay.

Yonatan Adler:

There were things which were questioned. I’d like to point out something here by the way. The fact that we have Judaism doesn’t mean that everyone’s agreeing on the details. Okay? So there were lots of arguments about exactly how to keep the details. We have groups like the Pharisees and the Sadducees, the Perushimand the Tzedukim, and the Essenenes. And we have the followers of Jesus that they were their own group. And we have, Chazal talk about the Baytusim, early rabbis talk about this other group that we don’t have outside evidence for. So all of these people were arguing about how we should be keeping these rules.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

None of them suggested that we don’t need to keep the rules.

David Bashevkin:

That there’s no such thing as rules.

Yonatan Adler:

There were arguments about how to keep rules. None of them were being particularly lenient versus strict. It was just a question of how these rules should be interpreted and put into practice. One of the examples of the things that they were arguing about was, do we need to keep rules that aren’t written outright in the Torah, but we’ve been keeping for a long time. So the tradition of the elders, it’s called.

David Bashevkin:

What’s an example of that?

Yonatan Adler:

Well, a good example of that is washing hands. So we know that from the Torah, from Leviticus, VaYikra, the entire body can become impure from various sources of impurity. There’s no real notion that one’s hands can become impure and that they can become purified. There is something relating to the zav, but the general notion is that one’s entire body becomes impure.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Yonatan Adler:

And one needs to wash the entire body in order to purify it. So where’s this notion of washing hands-

David Bashevkin:

Just your hands and not a full body immersion.

Yonatan Adler:

Exactly. So that’s something which isn’t written.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Yonatan Adler:

But it is something which had been practiced for quite some time and there was a question, should this be kept, should this not be kept, even within Chazal?

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

There was one of the Tanaaim that disagreed and thought there’s no such thing as-

David Bashevkin:

Tumas yadayim, as it’s called.

Yonatan Adler:

Exactly. There’s all kinds of quirks, but I don’t want to miss the forest for the trees-

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

… or the trees for the forest. And the question is, from what point in time do we have evidence for all of these things? It could be that some things we have evidence for earlier than other things, but that’s the question that I’m asking. Okay. So do you want to hear the punchline?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, let’s hear the punchline. I’m really fascinated by this. Growing up when I was a kid in yeshiva, the world of early Judaism, I think the wall of time it existed, but I didn’t even see it, because when you’re growing up, you just assume that whatever you’re doing now on the old illustrations and the Little MidrashSays, you just kind of superimpose whatever you’re doing now to what was going on in every time period, forever. Maybe with different clothes. Instead of wearing a jacket, they were wearing cloaks. But you basically retro project into the past, whatever you experience in the present, and the more that I mature and the more that I actually immerse in regular Chazal and particularly in the works of Rav Tzadok which we’re spending some time on, I appreciate understanding these shifts more. I think that they’re really important and they don’t need to be troubling. Well, as I’m sure we will discuss in a moment, so you went to the record and at some point the record peters out, I assume.

Yonatan Adler:

Yes. So the trail of evidence does end and before we get to the punchline where the trail of evidence ends, it’s important to be very clear about this. Where the trail of evidence ends means that before that time we don’t have evidence. So as everyone knows, absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. So the fact that I don’t have evidence doesn’t mean that it didn’t exist. It means that I don’t know if it existed or not. I just don’t know. I don’t have evidence. So in archeology we have a term called terminus ante quem .

David Bashevkin:

Terminus ante quem.

Yonatan Adler:

Terminus ante quem, so ante is like in Latin, this is in Latin term, ante is like antenna, right? So it’s what the bug has in front of it.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Yonatan Adler:

So it’s the terminus, it’s the terminal point in time before which.

David Bashevkin:

Gotcha.

Yonatan Adler:

So the trail of evidence ending means that this is our terminus ante quem, it’s the point in time before which Judaism must have begun. So where we no longer have evidence that people are keeping the laws of the Torah, Judaism must have begun then or earlier. Okay? That’s what I’m looking for. What I found with practice after practice, prohibition after prohibition with all of these chapters, I have found no evidence that the regular everyday people knew about or were keeping any of these laws before the middle of the second century BCE. So to give perspective, we’re talking about the Hasmonean period, the period after Chanukah, right? The period when Jews were living in an independent Jewish state in Judea, again, the middle of the second century before the common era.

David Bashevkin:

Now again, just the two disclaimers that we’ve been saying this relates to that definition of Judaism as you’ve been discussing, doesn’t mean that there weren’t Jews beforehand. We certainly have-

Yonatan Adler:

Absolutely not that we know that there were Jews. There’s no question about the fact that there were Jews, people that called themselves Jews, other people called them Jews. There’s no question. We have lots of evidence that-

David Bashevkin:

Sure-

Yonatan Adler:

Jews were living in the land of Israel, outside of the land of Israel before this period of time. The question is from which period do we have evidence that these Jews knew about the Torah and were keeping the laws of the Torah.

David Bashevkin:

And what you really said like as a social acceptance being socially synonymous.

Yonatan Adler:

As a social group, but there could have been a small number of intellectuals that knew about the Torah and thought the Torah was something that you should be keeping and maybe were even keeping the laws of the Torah. But I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in the masses. The large numbers of people.

David Bashevkin:

As an archeologist and as somebody who is teaching a class called archeology and halacha, you have training, deep knowledge and training in both areas. I’m wondering what you tell your students or how you help your students frame when they look at their contemporary lives wherever it is, whether they are secular Jews, Orthodox Jews, Mesorati in Israel, or Reform Jews, whatever practice they may be, and they want to make a contemporary decision based on the evidence of your research. They say, you know what, whatever the last chapter in Dr. Yonatan Adler’s book, what do your students call you, Professor Adler? It’s always a little less formal in Israel,

Yonatan Adler:

It’s less formal. They just…

David Bashevkin:

Okay. So they’re looking and they say, “You know what, I’m going to sign up for whatever the final chapter in this book is, and that’s what I’m going to do because I am going to base my contemporary religious life about reconstructing what that early origin period was.” Is that the way you suggest that they approach it? What are you looking for the contemporary applications of your research to be, if any?

Yonatan Adler:

I’ve yet to find a person who has come to me and said, “Professor Adler, I want to base my life on what Jews in the fourth century were doing. I don’t care what they were doing in the third century or the second. I just care about the fourth century BC. That’s all that I care about. So you tell me what Jews were doing and I’m going to do that.” Never met a person who said that.

I don’t see how the question that I’m asking in the book has any relation to what people would take from that in terms of what they would be doing in their life. What the masses of Jews were doing in the second century versus the third century, I’m sorry to say, but who cares? It doesn’t really affect our everyday life. When I teach my course on archeology and halacha, I like to start by quoting the Zohar. There’s a famous line in the Zohar which says in Aramaic, “Kudsha Brich Hu, histakel b’Oraysa u’bra alma” that means HaKadosh Baruch Hu, the holy One blessed beHe, God looked into the Torah and created the world. In other words, God used the Torah as the blueprint for the world. And I tell my students, this is an extremely deep sentence. This is an extremely deep quote from the Zohar. It would take me about 40 years to really hash out what this means. We don’t have 40 years, we have one semester.

David Bashevkin:

We only have one podcast so…

Yonatan Adler:

And we have only one podcast. So we’re not going to get into this quote, which every time I say it sends shivers down my spine, what does that mean? That the Torah is the blueprint of the world. So I can’t get into what the quote means, but I can tell you what it doesn’t, and what it doesn’t mean is that God literally opened up a Torah scroll and read what it said and created the world from that. How do I know that it’s not literal? Well, first of all, the stories in there are stories about things that happened after the world was created. We have stories about the patriarchs, Avraham, Yitzchak, Yaakov, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. We have stories about Moshe, Moses and we have stories surrounding these characters, which obviously didn’t happen before the world was created. So how could it have been written in this putative Torah that God used to create the world?

Perhaps even more troubling is the fact that we all know that a Torah has to be written on animal skin and it needs to be written with black ink. And how could there have been animals skins to write a Torah on before animals were created? Right? That’s just an impossibility. So what does that mean? Does that mean that we should take this deep, incredible quote from the Zohar and throw it out the window and say, no, this is silly. Of course not. This line wasn’t meant to be read literally. It was what I would call meta history. It’s not history, it’s not to be taken literally. This isn’t a historical statement. It wasn’t meant to be a historical statement.

This was meant to be a statement about what the world is, what the nature of the cosmos is. It’s just a very, very deep concept. And it’s true in the deepest sense of what that word true means. It’s not history. History is something completely different. History is what a couple of strange professors do in the university and it has very little effect on what people’s day-to-day lives look like. We’re talking about meta history, we’re talking about the Torah, which is not history. It’s something very, very different.

David Bashevkin:

I grew up and I think the world of archeology was presented as something that was subversive, almost dangerous, dangerous to explore this time period because I think rightfully so, people felt that the way that we look at Judaism and the way that it was practiced during this time period doesn’t necessarily cohere with the Jewish life that we’re familiar with. I grew up in Long Island, certainly a lot of the major touchstones of Jewish life… We don’t have records of really fun bar mitzvah parties or whatever it was in early Judea. But I’m curious that concern, that fear, does archeology in any way or should it in any way vindicate a particular approach to Jewish life? Does it have a value judgment on how Judaism should be observed today?

Yonatan Adler:

I think what you’re describing is a belief system which is standing on very shaky legs. If one’s belief system stands on this or that historical event having gone this way or that way, but this or that figure having been an historical figure or this or that event having happened, you’re standing on very shaky legs. Just like if your belief system is based on certain facts about the world being this way or that way. And if science discovers that it’s not the way your belief system would insist upon, then everything crumbles. I would call that a shaky belief system. Let me put it this way. I look at the world as made up of matter and what matters. These are two separate things. Okay? Science is the field that we use to try to understand matter, things like literature and what we would call religion and the myths and stories that we tell and the religious practices that we have and the rituals that we do, the festivals that we keep, this is what matters.

And these are two completely separate things. They might inform one another, but what matters isn’t based on matter, and the belief system that we have, our hierarchy of values, if it stands on a belief, I’m putting scare quotes here, a belief in something in the world of matter being this way or that way, that belief system is going to crumble really easily if scientists discover that whatever it is that we believe in is different than what science shows. So I would say that archeology in ancient history isn’t dangerous if our belief structure is built on solid ground, it’s only dangerous if our belief structure is built on quicksand.

David Bashevkin:

I really appreciate that. I love that line. The world is comprised of matter and what matters and I am so excited. I didn’t yet get my copy of your book. Hopefully it will be arriving soon. I believe it. It’s going to be published again by Yale University and arrives the end of November, I think November 29th.

Yonatan Adler:

The press tells me that it’ll be ready by the end of October.

David Bashevkin:

October.

Yonatan Adler:

You can already pre-order the book online on Yale University Press or on Amazon.

David Bashevkin:

Well by the time this airs, you could for sure order the book. There’s no question about that. And just your time and your ideas. I cannot thank you enough and they’re absolutely fascinating. I always end my interviews with more rapid fire questions and I was wondering if you could indulge me. You already mentioned the three volume work of Menahem Stern. You mentioned obviously your own work. I’m wondering for somebody who wants to learn more about the world of early Judaism, what we have evidence for, what we don’t have, what there is an absence of evidence for what other books would you recommend within this universe?

Yonatan Adler:

Josephus.

David Bashevkin:

The classics.

Yonatan Adler:

You need to read Josephus. I discovered Josephus when I was in fifth grade.

David Bashevkin:

Fifth grade?

Yonatan Adler:

Fifth grade.

David Bashevkin:

Where were you in school that they introduced Josephus to you in fifth grade?

Yonatan Adler:

They didn’t introduce it, but I went to the Hebrew Academy of Long Beach. HALB-

David Bashevkin:

Get out of town.

Yonatan Adler:

… back in the day when it was in Long Beach.

David Bashevkin:

I grew up right… My sisters all went to HALB.

Yonatan Adler:

So in the library, in the Library of Health, there was Josephus War, The War of the Jews against the Romans. I discovered it and I was hooked, fifth grade

David Bashevkin:

In the HALB library. My heart just fluttered. I’m a South Shore boy. So obviously we’re from different schools, but all my sisters went to HALB, my parents sent all the girls to HALB, and I’m not going to indulge you on the HALB graduation song, but I happened to have attended enough graduations that I could sing Galei HaYam, which is the song that they… I don’t know, did they sang that in your time?

Yonatan Adler:

They did, they did.

David Bashevkin: