Zahava Moskowitz: Singled Out

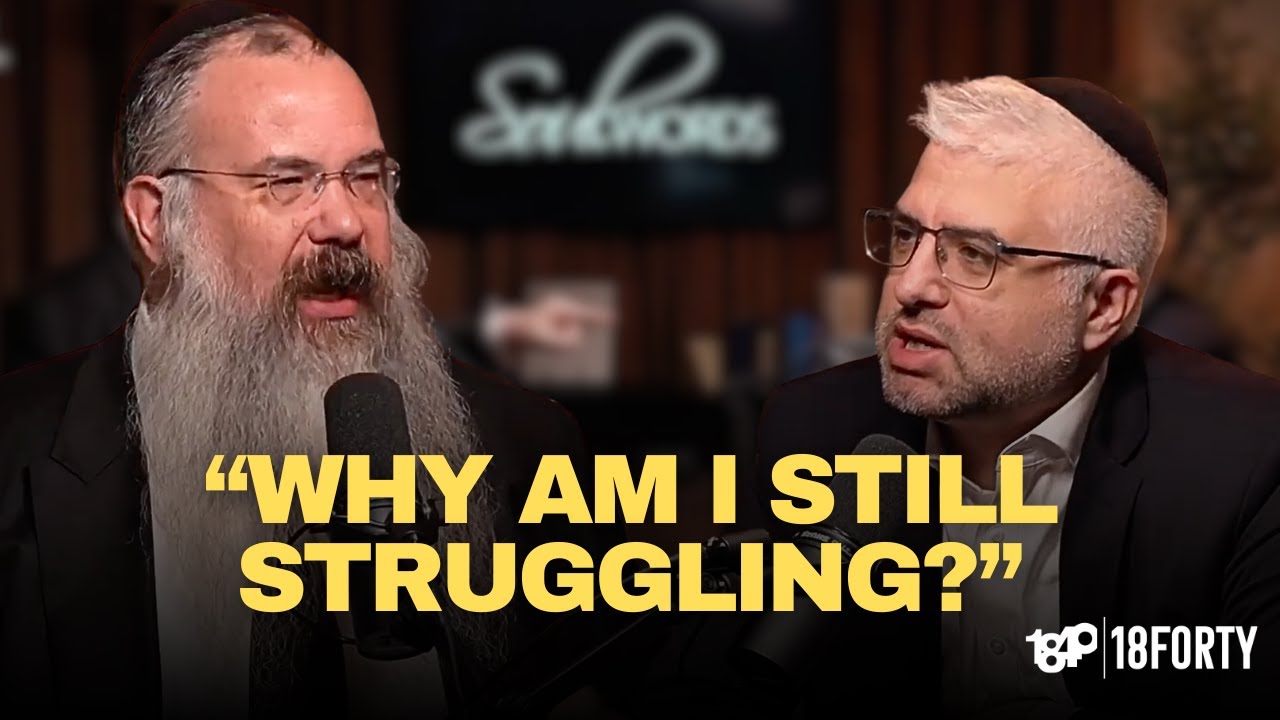

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Zahava Moskwowitz, host of the Singled Out podcast.

Summary

This episode was sponsored by Anonymous who is fond of Shalom Task Force & 18Forty

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Zahava Moskowitz, host of the Singled Out podcast. Zahava shares insight into the challenges of singlehood, debates the pros and cons of pictures on shidduch resumes, and brings us into the world of singlehood in the Orthodox community.

- What does market information asymmetry relate to dating?

- How do men and women experience the struggles of dating differently?

- What are the biggest controversies behind shidduch resumes?

- Do we have more than one soulmate?

Tune in to hear a conversation on the challenges that lie beneath the surface of dating in the Orthodox world.

Interview starts at 20:51

References:

Singled Out Podcast by Zahava Moskowitz

“The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism” by George Akerlof

“Younger Siblings Getting Married First” on the Singled Out Podcast by Zahava Moskowitz

“The Truth about Health” on the Singled Out Podcast by Zahava Moskowitz

“The Truth about Soulmates” on the Singled Out Podcast by Zahava Moskowitz

Sefer Akedat Yitzchak by Rabbi Yitzchak Arama

Marry Him, The Case For Settling For Mr. Good Enough by Lori Gottlieb

Hilchot Teshuva by Maimonides

David Bashevkin:

Hello and welcome to the 18Forty podcast where each month we explore a different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin and this month we’re exploring romance and commitment, the world of dating. But really it’s so much more. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number 1-8 followed by the word F-O-R-T-Y, 18forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.

I began teaching a course at Yeshiva University around, I think it’s more than five years ago, called the Jewish Public Policy. And when I began the course, I was finishing up my PhD. Thank God I finished my PhD in Public Policy and I had no idea what exactly they wanted this course to be about.

They had been teaching it for many, many years. It was on the book, some of the esteemed professors who had taught it previously. Rabbi Dr. Saul Berman, Rabbi Dr. JJ Schacter had taught the course previously or different iterations of the course and they wanted me to step in and really reimagine the curriculum and I wasn’t really sure. I’m like, “What exactly is Jewish public policy? Is this public policy for Jews? Is that how Jews look at public policy?” And I really re-imagined the curriculum from scratch. There is one week that I absolutely love, which is focused on a very specific theory. The way I essentially divide up the course is the first section is about public policy concepts and how they relate or are interpreted within the Jewish community. The second section is how kind of like secular public policy affects the Jewish community. And the third section is about how we develop a public policy of our own.

And in that first section about kind of just general concepts, there is a concept that when I was preparing the course, I realized was absolutely crucial for understanding so much of religious life, so much of communal life. And that is the concept of an information asymmetry. I always tell my students it is the least exciting sounding week, but I actually think it’s the most exciting concept. An information asymmetry. What exactly is an information asymmetry, and why am I so excited about it? Information asymmetries is a very pretty simple, pretty basic concept. A lot of the course and the way I teach it is based on the scholarship of somebody named George Akerlof, who I believe won the Nobel Prize in Economics for this theory. And he developed a concept known as ‘The Market for Lemons’. We’ll explain in a moment why on earth are we talking about this now? But let me lay out this theory and why I think it’s so crucial, not just for dating but I think for really religious life in general.

An information asymmetry is when you have a market where there are two parties in any market, there’s a buyer and a seller, but they don’t have the same amount of information, they don’t know the same amount. It could be … And this is true for any market. I am not an expert. I go to buy a car. I’m not an expert in cars. I don’t know how good this car is. So there this information asymmetry between what the buyer knows about the object and what the seller is able to know. Now, usually information asymmetry is the difference between what the buyer and seller knows is not so vast. It doesn’t vary so much.

If I buy a product in a store, I essentially know exactly … I buy a bottle of soda. I might veer towards like Coke. Obviously, our listeners should know by now that we don’t really tolerate people who prefer Pepsi over Coke. We could talk about this at length and some of the writings that have been and why Pepsi used to win some taste test. Malcolm Gladwell famously wrote about that, but it doesn’t even start with Malcolm Gladwell. I want to state for the record, if you prefer Pepsi over Coke, there’s no place for you in polite society. We’ll talk about that later. But in an information asymmetry, essentially there is a gap in knowledge in between the parties. Somebody knows more than the other party. And what George Akerlof essentially said is that when you are dealing in like a used car market where there is more possibility for like a … what’s known as a clunker, a bad car. When you buy a car that’s never been used, so you know this is a good car, doesn’t have any miles on it, it’s right off the lot, it’s wonderful.

So there is less of an information asymmetry between the buyer and a seller. The problem is he says when there is a vast difference, when there is a possibility that this is not good. Think about buying a used piece of clothes on eBay. Think about shopping online and you’re buying from a secondhand dealer, a secondhand seller. You’re not quite sure exactly what condition this object is in. You’re not quite sure what its history is. You’re not quite sure if it really looks like it does in the picture, doesn’t really capture it and you know it’s been used before. So, what happens? So George Akerlof has this theory which he developed in his work called ‘The Market for Lemons’. And he talks about used cars and he says that when you go to buy a used car because there is this possibility that the dealer is trying to sell you a real clunker, something that does not work, has not been used well, what ends up happening is the entire market gets depressed.

All used cars end up selling for less because you’re not willing to pay the same amount, certainly not the same amount as for a car that’s never been used. And now the possibility that this is a real clunker, that this is not a good car, it doesn’t drive well, it’s been fixed up, it has its engine replaced. So that devalues not just that one actual lemon, but all the cars in the used car market, the entire market becomes depressed. This is an economic theory that really helps you understand how trust is built in markets and how the lack of trust can affect a market. If there is not real trust in a market, then everybody within that market suffers. The buyer doesn’t have the confidence that he’s getting what they want and the seller does not get the price that they really feel that they deserve.

So, how do you deal with information asymmetries? And you’re probably beginning to realize where I’m going with this and I’ll apologize in advance for bringing an economic theory into something that is so deeply personal and human, but I actually find it incredibly instructive. The way that we deal with market asymmetries, with information asymmetries, is through something called signaling. That is one of the ways that we do it. Now, you may be familiar with the term “signaling”. If you get into fights online and you’ve used the term “virtue signaling”, virtue signaling, which comes from the very same theory, which means you don’t really possess virtue or you don’t have a way of showing the virtue that you think you hold. So you virtue signal, you show a outside audience, usually on social media, how virtuous that you in fact are without actually doing the hard work of embodying virtue.

Signaling is a theory that was developed by many. The person who I often quoted, somebody named Kenneth Arrow, later was built upon by somebody named Joseph Stieglitz. And really what signaling is that when you have this information asymmetry, you don’t know exactly what this item is that you are buying so to speak. You don’t really know what it is. So we signal, we show the market ways, we signal ways of having trust. How do we do this? We do this in ways big and small, a classic way of signaling. And you could ask yourself, think about when you go to eBay, what are the signals that you look for? Think about when you go to a second seller, a secondhand seller, what are the signals that you look for? So one classic signal is branding. You go to an aisle in CVS. You have two items in front of you, one is ibuprofen, one is … What is that? Advil. And they’re both in the same exact packaging.

One has the CVS brand logo or a generic logo and the other has Tylenol, Aspirin, Advil, like the real proper logo that you know. You’ve seen commercials for it online. You’ve seen that classic mannequin outline in the commercials. I don’t know if they still have these commercials online, but they used to be really common. And Jerry Seinfeld had a bit about it, and you see it’s like red in a certain place. So which one do you pick up? One is cheaper. But very often, people pick up the one that is more expensive. They are paying for the branding, they are paying for the trust. This definitely plays out when you buy soda. Nobody likes soda without any branding whatsoever. It makes you nervous. Is it going to be flat? You know you can trust Coca-Cola. You know exactly and then you pay the price for that signal.

One of the classic examples of a market asymmetry and signaling is when you apply for a job. The employer doesn’t really know if you are suitable for this job. They don’t really know whether or not you can do it. So what do they do? Some might give an internship and they’re just going to make a commitment for the summer before they really make a full-time commitment of employment. Obviously, they’re going to look at your resume and the resume is full of signaling. When you hand over a resume for a job interview, the applicant provides a resume, details all the educational achievements which may have had no relevance to the post applied for, but they do signal a willingness for hard work and application. You may put stuff in there that kind of shows a signal that you are a gracious person, that you are a kind person. You’ll talk about volunteer work, what boards that you’re on. But a resume is a way of signaling which really gets us to dating itself.

I believe that dating is a market with a classic information asymmetry. Both sides are trying to figure out the other. They don’t necessarily know whether they are suitable for one another. And there are certain dating markets that I think are depressed for all. Depressed, not they’re depressing. Though Lord knows, and we’ve spoken about this, they are, they can be quite depressing. But so to speak the value of them, the value of them. All the participants are suspicious of one another. There is not trust. There is this information asymmetry. So everyone has to jump through more hoops. The classic example of this is the moniker, which I absolutely hate, called ‘older singles’. Older singles, which we’ve kind of moved away from. Now we use the term … I think we moved to the term ‘young professionals’, which I think in many ways is kind of the way we don’t ever call something a used car. We now call them pre-owned. Why? Because there seems to be more trust. You don’t to be as nervous.

But I used to go to older singles events, I went to one. And there is this sense, and I’ll be honest, I mean, maybe I’ll get killed for this. I think there is a truth to this, I think parties are looking at one another … All of the singles are looking at one another. Single people, excuse me, are looking at one another and they’re wondering in the back of their head like, “What’s going on?” “What’s their issue” is oftentimes the way that it is phrased. What’s going on? Do they have commitment issues? Something else going on? Give me the one sentence explanation because I am concerned that I’m going to be stuck with, so to speak, a lemon. So we signal in different ways to show other people that we are suitable spouses, we are suitable romantic partners, someone who you want to go out with.

How do we do that? The way we bridge the gap of information asymmetry, the way that we build trust in this market undoubtedly is through signaling. How do we signal? That may depend what dating circle, what dating market, so to speak, you are in. Now, I really do want to apologize. I mean this sincerely. It can be painful to talk about this like a market, like I’m not a piece of meat, I’m not buying a loaf of bread. And I couldn’t agree with this more because I think ultimately the real knowledge of whether or not there is compatibility, the real knowledge of whether or not this relationship works is ultimately unknowable until you actually make the commitment. I would compare it probably most to hiring somebody for a job. You could look at the resume a thousand times and go through five job interviews, they’ll help, they’ll probably make you more accurate, but you don’t really know if this is a fit until you’re actually there.

That is true a thousand times over when it comes to dating, and I tell this to people all the time. The dating process helps you whittle down or maybe mitigate some forms of risk, but ultimately a relationship, the real relationship, the real connection only exists after you’ve made a real commitment because the relationship doesn’t exist until you’ve made that commitment. Beforehand, all we’re doing, not all, but what we are doing is we are signaling that this can work and we are trying to verify if this in fact makes sense. And different circles have different ways of doing this. A very popular way of doing this in the Orthodox world is something called a shidduch resume, which we talk about in depth in this episode. What do you include in a shidduch resume? You might include references, you might include where your parents are working. You might include what shul you daven in. But what’s really important to know because a lot of people …

I mentioned this and I think I even spoke about this earlier. I mentioned this in my class when we were teaching, I teach in Stern. And one girl in the back who’s absolutely wonderful, I’ll say her first name, she knows she’s wonderful and she knows I’m quoting her, Jillian. She raised her hands in the back and she said, “This has nothing to do with me.” And I said, “Au contraire, my dear friend. Everyone is playing this game.” Everyone is playing this game. Doesn’t matter whether or not you are dating in the yeshiva world, in the chassidic world or the modern Orthodox world or you are on Jswipe or you are meeting somebody organically, everyone is dealing with the stress, the difficulty of having a real information asymmetry. And we try to signal to show, to bridge the gap in our knowledge so we can build the trust to actually begin and find that commitment that relationships are powered on.

How we develop that commitment is obviously through finding that trust. But how do we signal? Let’s say you don’t have a shidduch resume. I think Jswipe, in many ways, a dating profile, is of course signaling what picture you use, how you describe yourself, the way that you write, the emojis you might use. When you meet somebody, quite honestly, you are dealing with a dance of a information asymmetry and signaling. Think about any time you’ve made a new friend, which as you get older is less and less frequently. But you meet somebody, you’re at some networking event and you meet somebody or you’re on a date and you meet somebody. You don’t know anything about them before and you’re meeting somebody. The first thing that people do, and there’s a name for it, is called playing a game of Jewish geography. Why do we play Jewish geography?

What’s the point of it? How do you win Jewish geography? Jewish geography is a way of building trust with information asymmetry. I don’t know you but I know that we know mutual people and your opinion of those mutual people, if you say you know my next door neighbor who I’m really close with and you say, “Ah, we went to school together, we’re actually really close too,” you’ve just signaled to me that I can have trust in you. Jewish geography is like the classic way of building trust in a market with information asymmetries. Now, even when I am speaking right now, I’ll be honest, I can get a little cynical. Feels like is that what all relationships come down to? Is there’s nothing real there. There’s nothing more organic there? Of course there is. But as you get older, we’re not six years old anymore.

When you’re in school, you’re in the same institution, you’re able to build these organic relationships. As you get older, I begin signaling and that asymmetry in the market begins to grow wider and wider. I think it’s part of the reason why it’s so hard to make friends when you are older. And I do believe there are two things to know and that there are two really important takeaways for anyone dating and it’s so much of the topic of this episode and really the next episode where we explore all of the different universes of dating. Takeaway number one is to understand the market, so to speak, that you are in, to understand what is the role of your dating profile, what is the role of your Shidduch resume? What are you trying to do and not trying to do? You are not trying to capture yourself, in my opinion.

You can’t capture yourself because that could only come out in person really connecting to these people. And it really only fully emerges after the commitment is made. That’s part of the mystery. But I do think you are trying to signal and the way that you signal in a smart way is by writing verifiable information or descriptions that you are fairly confident are not going to be misinterpreted. If you write that you are bubbly, that might mean something very different to one person than to another. I would stay away, personally, to adjectives that can be severely misinterpreted. And the main goal is that you want to actually meet this person and see, personality-wise, how are we able to connect to each other? So when people would ask me to describe myself, I wouldn’t do anything. All I would say is, “Look, you could ask friends how they would describe me. Here are people who know me. Mutual contacts, here are plans of what I plan on doing or professional aspirations,” which obviously gave me a tremendous amount of anxiety. But I understood what role dating profiles, shidduch resumes, were playing in the market itself.

The second takeaway I think is even more important and that is never ever confuse signals for the value itself. Never ever. And markets tend to try to convince us of that. They try to convince us that the signal, the way that we’re able to project ourselves, correlate actually to the essential value of our character and our person. And I think it’s really important, especially through the process of dating, that we understand the difference between the two. Our signals are not our value. Our signals can help build trust. Our signals can help a person feel more comfortable with us or be a topic of conversation.

But ultimately, our value can never fully be captured and the relationship and the value of the relationship can never be fully captured just by comparing two resumes regardless of what dating world you are in. And I think it’s easy to confuse the two. It’s easy to confuse the two because we often feel like we are the estimation of what we can get, or how many names you have is a popular saying in the dating world, how many options you have. But I think it’s so important to emphasize that these are market mechanisms for organizing a lot of people in one system who are all trying to find love, but it does not reflect and it will never capture your underlying value. And I know it’s like … It may be cliché or obvious or simple, but it’s not because I’ve lived through in my own life, as I discussed previously, forgetting what my underlying value was.

You get so caught up in a system and you struggle for so long and so deeply to find that love, that it is easy to confuse putting out the right signals to metastasize and begin to look in the mirror and say, “Am I deserving of love?” And to feel undeserving of love is an illness, is a sickness that I have grappled with and I think a lot of people have grappled with. And I think much of that emerges from confusing signals and confusing the market itself for the real underlying value. And I think being able to distinguish between the two and knowing the world that you are stepping into, and that is not a reflection of who you are, in fact, is a reminder that everybody needs. Because ultimately, all of life is contending with these information asymmetries.

Your professional life is contending with information asymmetries. Your romantic life, certainly in their early stages until that commitment is actually made, is contending with information asymmetries. And learning both how to enter and kind of work the game of that market, but also how to reinforce and embrace the underlying value that each of us have. And knowing that’s never captured within whatever world that we are in. Your professional value is not your resume, it’s not your title, it’s not who you are. These are mistakes that we make constantly in our community. It gets back to that question that I hate so much. So, what do you do? So, what do you do?

It feels like you are being stuck, that your entire estimation of yourself is being stuck into that small box of your professional responsibilities. And learning how to separate and disentangle those signals in the great information asymmetry that is life and relationships itself, I think gives us the space and understanding to ensure that our underlying value remains intact.

So it was with that introduction that I want to introduce a conversation with somebody that you heard. She interviewed me and we took clips from that interview in telling my own dating story.

This is really her story of starting the Singled Out Podcast, which I was so impressed with and I thought she had such fantastic guests who really discussed the struggle and contending with, I think a lot of these issues, signals and value. And we talk in depth about should Shidduch resumes, dating profiles, how they should work and how they should not.

It is my absolute pleasure to introduce our conversation with Zahava Moskowitz, the host of the Singled Out Podcast. It is my absolute pleasure to talk to somebody who holds the acclaim that it is probably not how you introduce yourself, but you are from my first class of students ever in Long Island University, probably a incident that we both prefer to forget, but somebody who I’ve kept in touch with here and there. It is my pleasure to introduce the host of the Singled Out Podcast. And now I’m going to butcher your last name because it’s not Zahava Moskowitz anymore, it is Zahava-

Zahava Moskowitz:

Grodman.

David Bashevkin:

… Grodman. Zahava, I hope it’s okay. Because you still go by Zahava Moskowitz in your email. So Gmail-

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah, don’t worry about it.

David Bashevkin:

I’m so excited to speak with you today and you really did something for the community and for so many. When you were single, you began a podcast called Singled Out that I thought was absolutely fascinating. Our listeners probably have heard the episode with me on it because we re-broadcast it. But I wanted to begin, how old are you when you began dating?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Dating?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Zahava Moskowitz:

I began when I was 20,

David Bashevkin:

20 years old. So fairly young. And at what point did you decide to say, “Hey, I’m going to start a podcast while I am single”? That’s the part that I found most fascinating. How far into it were you when you began this?

Zahava Moskowitz:

So definitely towards the end of my dating. I don’t want to say career or experience, but I would say I was 26. So yeah, close to two years before I ended up getting married.

David Bashevkin:

And how old were you when you got married?

Zahava Moskowitz:

27.

David Bashevkin:

27, okay. And when you began this, why did you start this? Meaning my biggest concern would’ve been, and I had this, I remember when I was single, that I wanted to limit the amount of public information about my dating experience and ideas to the public. You want to be as blank a canvas as possible. So when somebody suggests somebody to you, they’re like, “Oh, you have to listen to this episode, this person is not for you.” I even published … I didn’t publish under my own name about dating when I was single. I was too scared to do it. I published some articles again after I got married under my own name, but they were already in the public when I was single. Why did you start this?

Zahava Moskowitz:

So, no, it’s a great question. I definitely resonate also with the feeling of kind of wanting to be anonymous. That was probably the last piece of why I was holding out for as long as I was. I thought of it actually a year before I started doing it and I got scared of what it was going to look like and would people not date me because I published such a podcast? Would it be weird? Would guys be turned off or shy away from it? I started it because I personally throughout dating would always try to seek out resources that I found helpful. So whether that was certain self-help books or TED talks or people I’d follow on YouTube. And something that I felt was really lacking was I just didn’t think there was a Jewish voice for that, like an Orthodox Jewish voice that was helping. Because I think there’s dating in general that people struggle with and there’s a lot of overlap in Jewish and non-Jewish worlds.

But I felt like dating has an Orthodox Jew is a very specific niche and has its own special issues that I felt like was just missing. And I felt like the key of also having that religious component was very much lacking. So I just wanted something that could really cater to understanding where I and people that I knew were in this experience.

David Bashevkin:

It’s so interesting because I have a class in Stern and I posed to the class, “Where do you get your dating advice from?” And I happen to think this is an area that is sorely lacking across the board. And it’s interesting that you said specifically the Orthodox experience because one person in my class who’s not quite in what I would call the centrist Orthodox dating camp, raised her hand and said, “I’m not a part of this world. This is not how I plan on dating.” And I pushed back and I said, “I actually think that you are a part of, everyone is a part of this world.” There are little wrinkles in the Orthodox community, conservative community, Jewish verse, non-Jewish community. But the quest for commitment and learning how to sustain your own sense of self while nurturing that commitment is something that I think everyone is involved in one way or another. But I’m curious for you, did you have a target demographic? You mentioned Orthodox. Who were you trying to give advice for aside from yourself, obviously?

Zahava Moskowitz:

I mean, anyone that would gain anything positive or helpful from my podcast. I am so happy to be part of that process, but I was specifically trying to cover Jewish Orthodox singles.

David Bashevkin:

Do you think you skewed or do you think your episodes were catered to male versus female? Was there a gender component in there? Obviously, you are a woman and that was your experience. How did you balance the fact that this should reflect the different experiences for men and women when searching for commitment?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah, that’s a great question. Ideally, no. Ideally, I really wanted to try and be as impartial to both genders as I could be. The hardship with that and something I actually still struggle with because I am still publishing episodes, is that it’s very hard for me to find male speakers. So I’ve had a few guys that were interested and then back out last minute. That’s happened a bunch and I’ve just kind of learned-

David Bashevkin:

Meaning single men?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah, single men. I actually have one married guy also that said yes and is kind of not sure. So ironically, I actually found just women were a little bit less shy in this area. So if there is a voice, it probably comes across a little more feminine. I tried to make sure that the topics were things that maybe both parties could really resonate with and it has been really nice. I actually have had male listeners reach out to me and point out different episodes that they found chizuk in, but it might come across a little bit more female-geared. But I think just because I’m struggling to find guys to be on the podcast.

David Bashevkin:

Why do you think in so many other areas … I one time had a conversation with Dr. Malka Simkovich and she said that when it comes to academia, women, she has found, are more hesitant to speak outside of their specific field. That guys, if you email me and say, “Hey David, we want you to speak about 15th century Italian Jewry,” there’s this male impulse. It’s like, “Yeah, I could probably contribute something there,” and you just jump right in. I’m fascinated that it was the inverse when it came to dating that you have a harder time finding single men who are willing to jump on and much easier time finding single women.

Do you think that’s because, so to speak, it’s kind of seen as this is a bigger struggle or a very different struggle or more existential struggle for the women you were talking to and guys are like, “Hey, if I don’t talk about it doesn’t have to define me”? Maybe I’m suggesting something too early. But I’m curious how you would characterize with the people you spoke to of why women were more comfortable speaking about this than men.

Zahava Moskowitz:

So it’s interesting because an example that you gave, it sounded like women were uncomfortable speaking outside of area of expertise or that maybe they felt a little bit insecure about or wondering. I think what was surprising to me is that I felt like guys could totally relate to this topic and that actually took a while to realize. I think a lot of women think, “Oh, since guys have it so quote unquote easy because of the of shidduch crisis are just getting way more resumes or-

David Bashevkin:

Alleged shidduch crisis.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Alleged. Right, exactly. It’s interesting how you define it. I grew up with three brothers and I love them to death, but everywhere I went, they were constantly being pursued. People would always come over and ask me, “What’s their deal? Are they dating?” So I always assumed it’s so easy for guys and they don’t have the same struggle. And I think the further along I got as an older single, I started realizing that wasn’t true. And I found that after I was married, guys would be more forthcoming about it with me.

I just think in general, guys are a little bit more hesitant to be vulnerable in a public space, which is fair. Listen, I’ve had women also that told me they weren’t comfortable, but definitely less so. And I just think it’s something that they feel nervous to be seen in that way. That’s been my experience.

David Bashevkin:

Do you think that starting the podcast or the experience of being a figure who’s talking about this, do you think it helped you personally get married? Do you think it hurt you in any way or you think it made no difference whatsoever?

Zahava Moskowitz:

My parents, I definitely have to thank for this. But like all parents, I don’t give them credit because okay, their parents have to tell you, “You should do it, you should do it.” They were supportive of the podcast from the very beginning. One of my very good friends and my brother were actually a very big advocate to say that I should do it. I was really, really hesitant because I felt like similar to what you said with there being so much out there that you could find out or research about a person. I was really hesitant. Is this going to be something which defines me? Is this going to count against me? And it came to a point where I realized it really came after a breakup, if I’m being honest. I pinned it because I was like, “Nah, I don’t know if I want to go ahead with this.” And then-

David Bashevkin:

A more serious breakup, I assume.

Zahava Moskowitz:

A more serious breakup. And I was like, “Right, this is why I wanted something. Because I would love to have something to turn on and go to right now.” Because anyone who’s experienced a breakup knows it’s one of the most gut-wrenching pains that you can experience. So I was just like, “I’m just going to do it.” And I came to this decision that, okay, the right guy is going to appreciate this about me and not be weirded out or turned away by it.

David Bashevkin:

I’m curious if the advice that you got in the course of the podcast, did you find yourself following it? Did you change in your dating practices while you were doing the podcast? It comes to mind, there’s a rav who I knew who wrote a book on prayer and he one time confided something in me that I always think about. He said, “Ever since I wrote a book on prayer, I haven’t been able to daven as well.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Interesting.

David Bashevkin:

It hurt his davening. It became more maybe self-conscious, more mechanical and less organic. I’m curious for you, do you feel like you were more strategic and a smarter dater? How did you find it impacting the way that you went out with people? Meaning you just spoke about how it may have focused the pool of people you were going out with like, “Hey, I don’t want to go out with a podcast person.” I dated somebody who’s a fairly prolific writer and she speaks about this. People didn’t want to date her because she was a prolific writer and that whittled it down in a good way, in a good way. Eventually, she married somebody who initially did not want to date her because she was a prolific writer and wrote about her dating experience. And I’m curious for you, aside from whittling the dating pool and focusing it more, did you find that it was changing the way that you were approaching the process itself?

Zahava Moskowitz:

It’s funny, I resonate with what you said about the rabbi who struggled with tefillah to a degree. I wouldn’t say that in any way inhibited or harmed my ability, but I think I kept approaching the podcast kind of like a post-facto way to help with something that I had worked through, if that makes sense. So if I was going through something in singlehood and I was like, “Oh, I feel like I just kind of chapped this lesson or learned this lesson about this, I want to bring a speaker who’s going to talk about that.” So yeah, I think I approach it more from an angle of how can …

Who’s going to talk about that. So yeah, I think I approached it more from an angle of how can I give chizuk and I definitely gained a tremendous amount, which I’m sure we’ll get to from different episodes. Yeah, I don’t know. There was probably one of the things I could think of that did change, but I honestly think the ability to feel like I was contributing and helping in this area was what really helped in my singlehood. Because, and it’s something I feel very strongly about in general, and in singlehood, but obviously in every era of life, is that I felt purposeful. I felt like I had some type of creative outlet, but I think more of my own struggles and personal experiences is what ended up really helping me grow the most in my dating.

David Bashevkin:

So let’s talk about growth, change, and evolution. I asked you to do what I think is a very strange exercise, but I found it absolutely fascinating. We were in touch when you were single, to set you up. I think I may have even set you up, possibly.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah. I never never went out with anyone, but you definitely suggested a few people.

David Bashevkin:

Suggested a few times, hit and miss. I’m not so great.

Zahava Moskowitz:

No, but I so appreciate it.

David Bashevkin:

I’m not so great in this area. But one thing I asked you to kind of reflect on, as a window to mark your own evolution, was to go back and look at your own what is known as a shidduch resume, which is the worst branded item, I think, in all of Orthodox experience. And what a shidduch resume essentially is, you have a professional resume that basically explains what you are looking for professionally, your professional accomplishments. And there is a parallel shidduch resume, which is a profile. It’s not necessarily uploaded to a website. You would hand it to somebody, and it says a little bit about where you grew up, who the person is. And this is something that’s become fairly common in the Orthodox world. I guess in the non-Orthodox world, the parallel to this would be your JDate profile or your SawYouAtSinai profile, or something like that, a dating profile. But this is, we call it, and it’s awful to say it, but it’s what it’s called, right? A shidduch resume.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

And I asked you to kind of reflect on what information you put on the page, and how that information evolved through your process of dating. And I wanted to start at the very beginning. You’re 20 years old when you start dating, and you are told to make a shidduch resume. My first question is, did you make your own shidduch resume, or did somebody else make it for you?

Zahava Moskowitz:

So it’s funny you say that. I made my own, but I remember the first time the concept was even asked of me, I revolted. I was like, oh my gosh, no. There’s no way I’m going to make a shidduch resume. This is crazy. That’s insane. I remember being so upset by that. And the person who was trying to set me up was much further along in the dating career and were like, this is totally normal, what I’m asking you to do. And a lot of people actually do this and date that way. So I remember being like, no, I’m not going to do it. And if a guy’s going to ask that, I’m not going to go out. Which is funny, just to see how norms also change while you’re dating. And then, yeah, so once I decided to make it, I remember my dad just being very much like, why are you fighting it? Like just kind of play the game. If that’s what’s going to get you what you want, who really cares? Just make a piece of paper and put down information about yourself. So I probably asked a few of my friends just to see theirs to workshop and get a sense of what even goes on it. But I ended up making my own.

David Bashevkin:

There are a few things that I noticed on your shidduch resume, especially in the first one that I am intrigued about. There are two things that obviously jump out at you. The basic shidduch resume, like any dating profile, includes three areas that almost everyone has. Your education. What institutions have you been affiliated with? And you have Queens College, MMY, Central High School. Again, to our listeners, Zahava is already married. So we are not throwing this out there for suggestions. We are reflecting on it. But you have your education, what institutions you’ve been affiliated with. You have your family, who your father, who your mother is. You list, and I’m curious, I want to stop here. You list, and this is standard, you list your parents’ professions. Is this something that you ever discussed or had hesitance about? I have always felt that parents’ profession are an ugly stand-in for wealth that absolutely has a very quiet whispered effect in the dating world.

Zahava Moskowitz:

That’s really interesting. I’m embarrassed to say, I literally never thought about it until now. That was something that I…

David Bashevkin:

Oh my God. I don’t want to make you insecure. I mean, you’re married.

Zahava Moskowitz:

No, no. Listen, I can definitely hear that, because I guess it says something about your family and maybe the lifestyle you grew up with. But I’m so proud of my parents. My dad’s a rebbi, my mom’s a nurse, and it really was just something that I saw people had. So I was like, okay, I didn’t also get why people needed my siblings’ ages, what difference that made, but I just saw that everyone was doing that, so I figured that’s the norm.

David Bashevkin:

So you have your siblings and then there’s the place where you have references. Again, this is very standard, and you have basically the rabbi from your shul and then close family friends and close individual friends. When you put down the names of your individual friends, did you let them know beforehand that they were being put down?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Totally, yeah. They knew.

David Bashevkin:

Did you prep them? Do you have a conversation with that friend to basically get on the same page to be aligned? If you get a call, this is kind of what I’m looking for, this is what to look out for.

Zahava Moskowitz:

I didn’t, because I love my friends and trust them, but I have realized, with time, of making a lot of shidduch calls for friends. And I don’t want to throw guys under the bus. This might be something with guys just maybe not being as comfortable on the phone, but I found that it’s definitely worthwhile to just run through with your friends and make sure that you are on the same page. Because I think the best comment I ever got when I called for a friend, I called a guy that she had been redt one of his references, and he had no idea what to say about his friends. And I was thinking…

David Bashevkin:

I just want to jump in very quickly, and it’s probably not going to be the first or last time I make this disclaimer. The word ‘redt‘ is a Yiddish term that means to suggest a shidduch . It is the one Yiddish word that has become common parlance in the Orthodox community. Even people who don’t speak a lick of Yiddish. And I assume you don’t really speak all that much Yiddish, but redt, which sounds like reading a book or the color redt is actually the Yiddish word. Probably redt, which means to suggest a shidduch .

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah. No, thank you.

David Bashevkin:

No, continue. I’m sorry.

Zahava Moskowitz:

No, no problem. So I had called this guy and he really just had no idea what to say about his friend, which was sad, because I was thinking, he knows he’s a reference, because he wasn’t surprised. I texted him before saying, can I call you? And what he did tell me was he had a good jump shot, which is obviously important for every marriage. But I remember, honestly, being on the phone being like, you’re actually kidding right now. So I definitely think it’s worthwhile to make sure that your friends know. And just if you’re concerned about it, it can’t hurt. But I never have actually did a run through with my friends.

David Bashevkin:

The two most controversial parts of a resume for different reasons are what I would like to discuss briefly now, and especially how they’ve evolved. One is the picture, and number two is the personal description. Not everybody includes a personal description and there are different ways that people include them. Let’s start with the personal description. I’ve seen two things. I’ve seen people describe themselves, and I’ve seen people describe what they are looking for. Instead, you really focused on yourself. And I want you to read yours, the initial one, and maybe discuss how it’s changed. But I am not a fan of the personal description. I wouldn’t call myself anti-personal description, but if such a camp existed, I would be in that camp. Tell us your initial personal description on your first shidduch resume.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Do you want me to read it verbatim?

David Bashevkin:

Verbatim.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Okay. I did actually include looking for it, but it’s a small one-liner. So I am very much a huge fan of the personal description. Mine says, my first one, this is from 2017. I really enjoy meeting new people and hope to share a very open home one day. I love traveling, history, and trying new things. I’m passionate about education and kiruv. I’m looking for someone who’s warm, open-minded, excited about life, and growth-oriented, which I know is a word that you hate, but.

David Bashevkin:

We discussed this. Growth-oriented.

Zahava Moskowitz:

I know, but that’s what I wrote. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

How long did it take you to write that? The reason why I don’t like personal descriptions is I find that there are so many stand-ins for the personality that are best transmitted through experience. And I think the shidduch resume should just be to eliminate red flags or irreconcilable differences. And when it comes to personality meshing, I think you should share as little information as possible, because it’s being transmitted through a second party, the person setting you up, and they might read something. Like I might read this and say a very open home, this doesn’t sound like somebody who is that serious and religious. I may get a certain connotation. I think the most classic connotation is the word, and this is very gendered, when women are described as ambitious. When I was dating, I would listen very closely, I’d lean in. And if you heard the word ambitious, it was a stand in for a certain type of personality.

Now I am not excusing that bias, but my advice is usually to share as little as possible in terms of personality, because you really can’t know if it’s going to click, unless you meet one another. And the only thing it can do is exclude somebody who could have been relevant and now they read something. Nobody’s reading this and saying, yes, I am excited about life. Meaning it doesn’t narrow down the playing field at all. So it doesn’t really serve a purpose. That’s my personal feeling. What did you hope to accomplish? Was there something that you were trying to narrow down through the personal description?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah, totally. And that’s why I’m actually going to push back on your comment, because I specifically use the description to do exactly what you said, was to weed out specific people and to make it very clear what I was looking for. And I definitely think other people’s descriptions were probably the most helpful bit that helped me weed out others. So that obviously being said, there’s a caveat of, I’m sure that there can be so much written about not looking too much into certain words and nitpicking, et cetera. But when someone comes across a certain way in their description, it does send a clear message. You chose to write something specific here, so if it’s off-putting in the description, it’s worth looking into. Whereas I feel like if there’s no description, I have no information now, and I have to basically go on just what the person who’s recommending it is going to tell me.

So I really wanted to accomplish trying to show a balance of, I’m genuinely frum and looking for someone that wants a certain lifestyle that’s going to be motivated, including a life of growth with Yiddishkeit and Judaism. But I still want to have fun, and I’m looking for someone fun. That’s something that I actually think I struggled with a lot. And thank God I really dated wonderful, wonderful guys. But a lot of the guys I was suggested were very quiet and shy. So there was two things happening there. One, I was like, okay, I am probably giving off a certain impression. In which case then I think sometimes I anchor too much onto the description, to read between the lines. I’m not quiet and shy. That’s what I was hoping for to be like, I like life, I like trying new things.

David Bashevkin:

You don’t want to come off over the top.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

You have to thread that needle.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Right. And I think also it was my chance to basically try and figure out why am I getting suggested a certain type of person. So I think for many people the description box feels like the only area they have a little chance to show themself. And I feel like I get why people really, I mean, even go through mine, but tweak it and change it and spend so much energy at the end of the day. Obviously everything is from HaShem and when it’s meant to happen, et cetera. But I do think, for a lot of people, they do learn a lot about someone from the description. In my experience.

David Bashevkin:

No, it’s very interesting. I like a description. I like objective measures. That’s what I like, because it’s more discriminating, and it really gets to the point more rather than adjectives. Warm, open-minded, excited, and of course my personal favorite, growth-oriented. To me, there’s so much subjectivity there that I feel like when you use these kind of adjectives in a shidduch resume to describe yourself or describe what you’re looking for, in this case, they’re so subjective that like who am I really narrowing down. I guess the best term in here. Excited about life? I mean, I guess you’re going to narrow somebody who’s depressive and in bed in fetal position the whole afternoon. That person’s not excited about life. But I’m thinking about myself. Would somebody have described me as excited about life when I was 21? I would’ve looked into that and said, oh, this sounds very peppy to me. Too peppy.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Oh, interesting. Okay.

David Bashevkin:

Everyone’s reading into each one that I would’ve sooner said, I’m outdoorsy, I like hikes, I have certain hobbies that I like. That just gives you a picture. I didn’t have this as part of my shidduch resume, but I probably would’ve put loves to read. That kind of stuff. But even that, I’m pushing back on myself now. I wouldn’t have put that on there, because my issue was not being set up with people who were too quiet. My issue was being set up with people who were too intellectual. So I didn’t want to give the description. I didn’t want to give any fuel to the fire of the subjective interpretation of the people reading this to read into it. Say, oh, he likes reading. We got to set him up with a librarian. That’s the only way, that’s the only person he can marry, right? People are so Amelia Bedelia, so literalists like, oh, excited about life. I one time saw this person frown. We can’t set them up with Zahava. It gets so boxy that I prefer my, but I like your pushback also. I’m curious for you, you edited this and this evolved your personal description. What edits did you make, and why?

Zahava Moskowitz:

So the two edits I made the most, I’m going through it now with you, are the pictures.

David Bashevkin:

We’re going to get to the pictures. That’ll be the separate thing. Yes.

Zahava Moskowitz:

The description.

David Bashevkin:

How did the description change?

Zahava Moskowitz:

So it’s funny. I think what really changed the most is how I just was trying to convey, and this is going to sound cheesy, but I really was looking for someone that just was so excited about being frum and wanted to grow. And I think depending on the types of guys at the time I was being suggested, I would tweak it. So if I was getting suggested very modern guys, who there was definitely a time I was more open to dating that because I was like, okay, let me see. Because I mean, not in a mean way, but I did find that guys that were more quote unquote modern were also more interesting and fun, in a lot of ways. And I had a hard time finding that balance. So I would date guys like that and then I would be like, okay.

David Bashevkin:

When you say modern, it’s such a subjective term.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah, yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Is that a stand-in for somebody who wears jeans? Let’s just call it out. What do you mean by modern? Somebody who has a- it’s not between kollel, and that’s not the distinction. When you say modern in the most stereotypical way, what comes to your mind?

Zahava Moskowitz:

The most stereotypical way, someone who’s more modern is someone who probably, I guess dress is part of it. Although for me it’s just more, usually someone that’s more cultured, is more willing to do fun activities, has an appreciation for TV and music. That’s like bare, bare, bare bones what I would say is more quote unquote modern.

David Bashevkin:

Who could I watch The Office with?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yes, exactly.

David Bashevkin:

Who knows pop culture? Okay. Gotcha.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Hip and into all of that, yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. So your description changed, because you are trying to find somebody who’s fun, but also quite passionate about their Yiddishkeit. Now, what was the word you used to describe that? What was your, on that spectrum, if one side is modern, was the other side term you would use yeshivish?

Zahava Moskowitz:

In terms of who I would date?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Zahava Moskowitz:

So I did go out with some guys who are yeshivish. I would probably say more to the right of modern. Obviously, that’s in the spectrum. But guys that I think were maybe too heavily focused, I don’t want to say too heavily focused, that sounds bad. I think that what was the only thing that was really going on in their life was Yiddishkeit, and there wasn’t a sense of personality or a zest or appreciation also for enjoyment. So sometimes it was a yeshivish guys and other times it just was guys that were genuinely frum, but yeah.

David Bashevkin:

And how did you correct for that on your personal description? How did that evolve?

Zahava Moskowitz:

So if I would say what changed, it would be, like for example, in the beginning when I was getting very, very sweet frumguys that were very, very quiet. So I initially wrote passionate about education and kiruvand a lot of guys would respond back, or people that was trying to set me up would say it was coming across that I was very frum. Because if a more modern guy was reading that, oh she’s passionate about kiruv, she wants to be a rebbetzin, she’s way too frum for me. Then I was like, I’ll tweak that, right? I’ll change that a little bit. Someone who is open-minded and interested in growth. And then when I felt like I was dating guys that were too modern, I would compensate by saying who wants to? Oh, wow. I was really striking this one. I’m looking for someone who shares my excitement to enjoy life and build a home of Torah and mitzvot. And it also mentions who is passionate about their avodas HaShem. Yeah. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

That’s a lot. I’m making a face now. It’s a lot. You hear it, right?

Zahava Moskowitz:

No, and that was definitely after I spent a year. I was in Israel two years ago doing a Tanach fellowship, and I just felt very reinvigorated and reinspired by what I was looking for. So you could definitely see there’s a clear tone of what I’m looking for there.

David Bashevkin:

What I like that you did well, and I only have one kind of note, and issue. I love that you added in an emoji. You wrote in your later one, it says, and a little bit of a history nerd. And next to nerd you did the nerdy emoji, which I think is playful and shows, it’s a certain type of, it’s the cool nerd that you did, which I think is very fun. The other thing that I’m intrigued by is later on, you mentioned in your description, I’m going to your description, you have about five or six iterations, and then we’ll move on to the second thing. You wrote, I really enjoy positive outlets like traveling, almost anything nature related, quality time with family and friends and watching slash listening, then you wrote in parentheses, appropriate movies and music. I am so intrigued that you felt the need in parentheses to write appropriate. Is that because you were worried that admitting that you liked watching movies would be a signal that would remove you from more committed, frummer type of guys?

Zahava Moskowitz:

No.

David Bashevkin:

Or is it actually true, you will only watch appropriate movies?

Zahava Moskowitz:

No, it’s actually true. I mean, I think it’s hard to find a completely appropriate movie with no reference or language, et cetera. And I think everyone has different thresholds on what they view as appropriate. I grew up on movies. Love movies, my brothers and I quote them all the time. But I was specifically writing that because what I was looking for in somebody else. I appreciate being able to go back and forth with someone or someone who would get certain references, which I’ll say about myself, that definitely isn’t the most important thing to be looking for someone. But I do think when you come from a certain world, you just feel connected that you share a background with someone in terms of how you grew up or certain references. And for me, music and movies were such a way that my family grew up and connected, and had so much joy and fun in the home that I wanted to share that with someone.

So that’s why I wanted the caveat of I like that, but in an appropriate measure. I did go out with someone that grew up very similar to me, but he really wanted to divorce from that mentality, and was very against watching anything. So it begins this conversation of like, okay, you’ll do your thing, I’ll respect you, but what’s in the home? And I just saw that it couldn’t work. And the funny thing is that I feel like the more progress and busy please God you get in life, the more I realize, wow, if I had time now to watch certain things, that’d be amazing. And it’s such a big deal in the moment, but I just think it showed a certain type of outlook and mentality that I was really trying to weed out.

David Bashevkin:

It’s so fascinating. And as an exercise, most people don’t have a record of their self-description through time. But if you do have one, in your own life. I think to myself, I’ve mentioned the story 101 times on this podcast when Rav Moshe Weinberger called me up and asked me to go out with a girl and was describing her yiras shamayim and I said, I’m not there anymore. I’m thinking about my own self-description and how it has evolved. I think it’s an exercise that is not exclusive to the dating experience. I think it’s an instructive exercise, like a window to see your own evolution. Which really brings me to the second part of the resume, probably the most controversial part of the resume, which is that you included pictures. So let’s just begin at the very basic. Are you in favor of including pictures on the resume, or are you opposed including pictures on a resume?

Zahava Moskowitz:

I personally am in favor.

David Bashevkin:

What do you think the two sides are in that debate?

Zahava Moskowitz:

I think the two sides in that debate are it’s really hard to capture someone in a picture. To be fair, it’s hard to capture someone in a resume, also. So again, it’s a way to weed out the extremes. But I also think there’s way too much emphasis put on this piece of paper of like, well, he didn’t say this, so- And I think pictures are the same way. I view them as a way to weed out anyone that I knew that’s not for me.

And attraction, I think there’s a spectrum and I think it can grow and everything can change. But I definitely, I think the pro side of that argument is, it’s not fair to waste anyone’s time. And I think that’s valid. I think attraction is a really important component to any romantic relationship. And if from the get-go something is not going to be for you, then I think that’s worthwhile to know in the beginning stages. Especially because I had friends that were the opposite of me, in the sense that they loved dating people and going out and meeting. I was not like, that because I’m more introverted. I also was way more emotional when I dated. So if I dated someone and it was a total bust, I would kind of go back into the emotional realm of, oh, back to square one, this is so hard, this is so annoying, is it going to happen? So for me, I’d rather know that it’s a shayach idea from the get-go and that wasn’t going to work out.

David Bashevkin:

It’s relevant.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Thank you. Yeah, that’s a relevant idea. And I think a picture in some ways can help with that.

David Bashevkin:

It’s interesting. It’s a span over a couple of years. You changed a little bit, but you have no less than probably five different pictures that you included here. How much thought, I assume you’re not just doing that randomly. How much thought goes in, and I’m just so intrigued by your opening. It’s a very classic stereotype, the cropped out wedding picture that in your first resume, not only is it cropped out, but there is a stray hand around your waist, which is very, when you see it’s like, who is that? Who is that? What is going on? Is this from a previous marriage? Because it’s not quite clear whose hand that is, but I’m curious why you changed from that opening picture, and why you were changing, swapping out pictures so often.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Totally. This was just for me, and this is not the case with all women, but I think a picture is something which a lot of people feel very insecure about because you want to feel confident. And the sad reality is, and again, for better or for worse, I think that’s usually the thing that makes or breaks a shidduch the most. There are obviously other factors and components, but I think knowing that there is pressure put on this picture, a lot of thought went in for me. And I’m scrolling through now and just laughing, like how many times I swapped it out of wanting to put a picture.

But something which was a real goal of mine was I was never a fan of the pictures that were super dolled up. I mean, I’m laughing because this one at the wedding is like, I just don’t look like that, so I don’t know what I was doing there. But I think in the beginning I was like, this is what everyone does. Everyone does this super made up picture with their makeup and hair that they don’t look like ever, except for that one evening of the year they’re a bridesmaid. And I put that on, and I think throughout time I was like, that’s not me. I don’t look like that. I want a picture that obviously shows an attractive version of me, but that will do me justice to feel like this is how I am, and this is how I smile. This is what I look like on a day-to-day, and I want that to come through.

David Bashevkin:

I am hesitant to ask you this question. I’m a little bit hesitant, but I’m going to go ahead and either we’re going to leave it in and people will write letters, or you’ll say, I don’t want to answer it, and I’m going to take it out. There is a brief stage in your pictures where your tznius standards varied ever so slightly. And I am curious- very slightly. I’ll be direct, you have a one year where it is clear that you are not covering your elbows, which is a de-marker, especially in the dating world, which is so hyper-focused on these different signals of what community you belong to and affiliate with. I’m curious if you could talk about whether or not that was a choice and what choice you were making.

Zahava Moskowitz:

It’s so funny, what you’re picking up on. I love it. I appreciate the question. Yeah, for sure. And I think if you notice the personal description there, it’s lacking more of the avodat HaShem lingo we were talking about before, because there was definitely an evolution for myself also religiously about how I would change, and things I was more and less with, I definitely pride myself on being a halachic person. And the halacha that I learned and studied both in high school and seminary and with mentors after, I was comfortable with the sources that said a tight sleeve above the elbow is halachic, and everyone can feel for sure differently about that. But that was what I decided, and I think what helped me feel comfortable in myself at the time. So because that’s what I was doing, I think I wanted to be authentic in that as well. And I think this comes up with pictures also where it’s like, well, if I would do that on the date or if I do that in my life, why shouldn’t I put that in the picture? They should know that about me upfront. So whether or not that’s maybe the right thing to do, that’s what I was going for there. I wanted the guy to know. Yeah, I’m halachot, and that’s something that I do and that’s how I dress.

David Bashevkin:

Did you deliberately move away from that? Because it was just one year, and it doesn’t appear again.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah, so it’s funny, I probably did. I definitely wear it less now. I don’t think it’s less halachic. Ironically, I had stopped doing that, and then did it again right before my wedding, just because the sleeve.

David Bashevkin:

One last hurrah?

Zahava Moskowitz:

No, no. I mean, maybe. The wedding dress itself.

David Bashevkin:

We’re going out partying, what are we doing?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Yeah. My wedding dress was on the elbow. But to be fair, that was really because it’s hard to move in a wedding dress. God bless.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. No, no. I just want to be clear, my question was not about one’s personal tznius practice. My question was about how we signal in different ways, and the choices we make to make those signals. Because the way I view all of dating is it’s this information asymmetry. The parties don’t know one another, and we have these subtle ways of signaling to one another what our authentic personality is like, what our authentic religious commitment is like. Something that you never really know completely until after the commitment. That’s, to me, the scariest part of dating. You don’t really know anything completely until after the commitment, until it’s almost too late. Because you’re not invited in. And also it doesn’t exist completely until after the commitment. There’s something that’s only born after the commitment, your religious life in the context of a committed relationship, your personality in the context of a committed relationship. That doesn’t exist until after the commitment. So the only thing we’re left to do is approximate and signal to one another what we hope to create and what we hope to have with one another.

Zahava Moskowitz:

For sure. So then to answer that question, yeah, it very much was intentional, and it was to give off the authentic message that I wear sleeves that are right above the elbow, and I was okay with that.

David Bashevkin:

I want to move and talk a little bit about the advice that you have gleaned through the podcast that sticks with you most. And what I wanted to do is go back to some of the episodes that resonated most with you and maybe listen in on the parts that you found resonated the most, and why they resonated so much with you. So which episodes, or is there a central idea that stands at the heart for you, as a person, that you gleaned from this experience?

Zahava Moskowitz:

I think it’s hard to narrow it down to one central idea, but the episodes that definitely spoke the most to me, I would say there’s three main ones. Again, I really enjoyed recording all of them and I’m so thankful. But I would say.

David Bashevkin:

And I asked you to not consider my episode, just as a disclaimer.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Right. No, I did want it right. I definitely wanted to include that. The three aside from that, I would say, are “When Younger Siblings Get Married First”.

David Bashevkin:

And that was with who?

Zahava Moskowitz:

That was with Miriam Borenstein White.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Zahava Moskowitz:

The second would be the “Truth about Health”, which was with Rachel Tuchman. And the last one would be “The Truth About Soulmates” with Esther Wein.

David Bashevkin:

So take me through each one, and we’re going to listen in on some of them. Set me up. Who is Miriam Borenstein? I happen to know her personally, but who is she? Why did you reach out to her? And let’s listen in together to see what she had to say.

Zahava Moskowitz:

Sure. So Miriam has a really, really special place in my heart. She was my favorite high school teacher, and I developed a really close connection with her during high school. She just was this role model for me throughout high school because she was so beloved in this school, and for a good reason. But she was single, and I think I really looked to her to see someone who embodied just someone really loving their life and growing. And that was a balance for myself that I really wanted to strive for, of constantly growing in my relationship, a connection with HaShem and with Torah and mitzvot, but just also while having fun and enjoying what life has to offer, and creating and developing myself. So following her throughout that experience. And then I’ve really been fortunate to get to actually develop a relationship through different experiences and working together, to being friends as well. So I knew that she would definitely be something that I wanted to have on when I started the podcast.

David Bashevkin:

So let’s listen in to your conversation with Miriam Borenstein.

Zahava Moskowitz:

The first part comes up in the first few minutes of my episode with Miriam. It’s funny, she just mentioned this pretty offhandedly when she was talking about being single and I asked her about her experience, how long she was dating for. And she said something along the lines of, the hardship was when she was ready to be married versus when HaShem decided she was going to be ready to be married. And that one little piece really, really spoke to me, because I do think there’s this humbling reality when you’re single, of you are ready for something to fill in, and obviously this could be applied to any area of life. But then the realization of, but it’s not happening, so clearly it’s not supposed to happen right now. And I think this gumball machine complex almost develops, which is something that I really had to work through in my relationship with prayer. Because I’m doubting for it, I’m praying for it, I’m asking for it, I’m checking all the boxes and doing all the right things. So why is HaShem not filling this in for me? And I think that development for myself personally was very humbling, and took a long time to be okay with understanding that our picture of what we want doesn’t always match up with what HaShem‘s timeline is. And that can be a really hard space to live in the interim, before that thing comes to fruition.

Miriam Borenstein:

I think for me it was wanting to be at the next stage of life. Wanting to find that someone and settle down and start that new stage. The conflict of when I was ready for it and when HaShem told me he was ready for me to be ready for it was a little bit different. So I think that that was probably a very big struggle.

Zahava Moskowitz:

I definitely hear that. That struggle contending with just because I want it now doesn’t mean I get to have it right now. That could be really hard.

Miriam Borenstein:

Right, and not knowing exactly when it was going to happen or if it was going to happen. Trying to keep in mind that you could be hopeful and want something, and also be humble to recognize that there is a greater plan.

Zahava Moskowitz:

The next piece was when Miriam talked about, she had multiple siblings that got married before her, but specifically her younger brother getting married first and how she handled those feelings. So she puts it so poignantly of saying that she had to make space for holding two separate emotions, which I also thought was just so real because she wasn’t denying the fact that hearing about her brother moving in a stage that she wasn’t in and wanted so badly was hard.

She very much explains that it was, but it also was conflicting for her because it came with this understanding of, “But I’m also so happy for him.” And I think singles experience this in so many ways, whether it’s a family member, whether it’s a friend, whether it’s a student. I think there comes this moment where you are torn with feeling both these ways and sometimes there’s a tremendous amount of guilt that is associated with that.

And I love that she just expressed that being human doesn’t mean we experience emotions in a vacuum because we’re nuanced, and part of being human and enjoying the human experience is really recognizing that feeling different and imposing things at the same time is extremely normal. And very much a Jewish concept also, if you think about certain experiences we have in history or just holidays that we celebrate.

And I think that was actually a very helpful piece of advice for me to hear because it allowed me to have space to be kind to myself when I would hear about someone that I deeply cared about, who was moving on to a stage that I wanted while also recognizing I can separate that and it doesn’t mean I’m not happy for them.

Miriam Borenstein:

He was actually very sensitive when things started to get very serious and he knew that he wanted to get engaged and move forward with his relationship. He asked for my permission to do so, which was something that was really sensitive and really thoughtful. I remember we had a conversation about it and of course I said, “For sure and we’re so lucky that you found your wife and that you’re going to bring her into the family.”

But I think that was the first time in my life that I experienced something that I think helped me through what I was going to experience when my sister got married and something that I still hold very much a major lesson in my life even now, which is that, in life you could really feel two things at the same time.

Sometimes that’s a really important thing to recognize that you could feel so happy for someone else and you could feel like this is the right thing and this is a great thing, and at the same time feel horrible about where you are at and so why things aren’t moving forward for you and feel a sense of despair like, “Will this ever actually happen for me?”

And the duality of that feeling was so strong that I still think about it today, not in that context, but that there are a lot of times in my life where I could feel two things at the same time. I could feel very happy about something and also I could feel some very disappointed or I could feel angry and it makes it a real raw emotion that sometimes just needs to be validated.

And I definitely remember feeling that way when my next sibling got married for me. Which was I was so happy and so excited for my sister to also be married and then also really feel like, “Is my third sister going to get married before me, is my youngest sister going to get married before me?” So that was a very important lesson for me to know that you could experience two things at the same time.

David Bashevkin:

To me, this is such an important topic and it’s something that I experienced. I have three sisters and my middle sister got married before my older sister and they were both engaged and their weddings were only a few months apart, but the way that this affects lives is very real. The way it affected my life and the lens that I look at it, I always think about Tisha B’Avand Purim as two friends who were dating together and Purimgot married first.

That’s why on Purim, I always imagine that at this wedding of Purim itself, if Purim was a ki’ilu, so to speak, a person, it pulls in the tropp, the cantillation, the intonation, and the leining of Tisha B’Av into the center of the circle as a reminder of bringing its other friend who was still… Tisha B’Av is a Purim unfolding to hold those two emotions together.

And that’s always something that resonated with me, not because as an idea because I experienced it. I experienced it with my own friends, I experienced it in my own life. So take us to the next clip, which is absolutely fascinating. I think it’s a really important point.

Zahava Moskowitz:

The next clip is basically when Miriam talks about the importance of having interests and pursuing passions in life. She talks about her experience. She actually pursued cinema comedy for a time, which I thought was just incredible and she’ll be embarrassed if I admit you can watch her on YouTube. But she talks about how specifically when it came to being at her siblings weddings and how she handled comments from people like the “Im yirtzeh HaShem by you”s that having pursued, she actually did the program that I did and it was inspiration for me doing it, the Tanach program I mentioned in Israel, that having that as a background really helped her have conversation to speak to people about.

Because very often people dread the Im yirtzeh HaShem, you know, please God soon by you comments and people are so well-meaning. But very often people see a single, I think what people struggle with is they feel defined by a single or people just they mean well, but they want to know the hock, are you dating? Are you seeing anyone? Are

David Bashevkin:

You busy?

Zahava Moskowitz:

Are you busy? Right. And I think it’s so important that she was explaining, having something that she was really loving and growing in was an amazing conversation topic to be telling people about. And I think when your whole world becomes so focused on dating and the goal of getting married, it can very often become that you’re worth in value become based on the outcome or lack thereof. And if it’s not happening, so what does that say about me? Why isn’t that happening for me?

David Bashevkin: