Summary

This series is sponsored by our friends, Daniel and Mira Stokar.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, tech entrepreneur Antonio García Martínez discusses his powerful “Why Judaism?” essay series, chronicling his conversion to Judaism and his views on the deficiencies of secular liberalism. A formerly Orthodox man who was moved to change his life after reading Antonio’s essays chimes in.

- What is the toll of a culture of optionality?

- What is the value of unchosen commitments?

- How does Antonio reconcile his deeply scientific worldview with Judaism?

Interview begins at 10:21

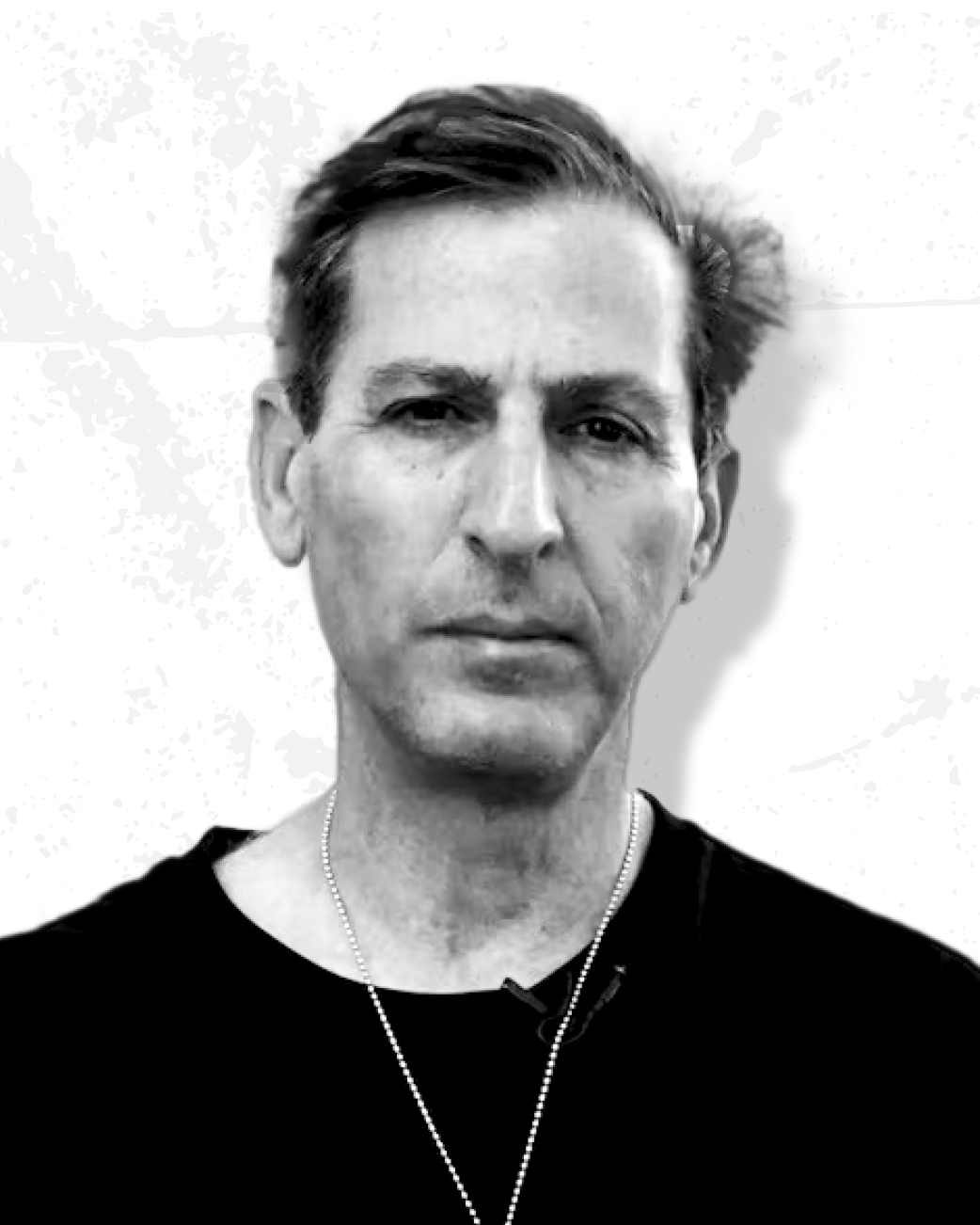

Antonio García Martínez is a New York Times best-selling author and tech entrepreneur. He is a former product manager for Facebook, the CEO-founder of AdGrok, and a former quantitative analyst for Goldman Sachs. His book Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley, an insider look into Silicon Valley, was a New York Times bestseller. Antonio reflected on his choice to engage with Judaism in a deeply thoughtful piece, “Why Judaism? On abandoning secular modernity.”

References:

Why Judaism? On abandoning secular modernity by Antonio García Martínez

Why Judaism?, part שני: On the question of God in modernity by Antonio García Martínez

Nineteen Letters by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch

The Benedict Option by Rod Dreher

Rethinking Sex by Christine Emba

Seven Types of Atheism by John Gray

The Sabbath by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring teshuvah.

Thank you so much to our generous sponsors, Daniel and Mira Stokar, for graciously sponsoring the entire month’s series. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s one eight F-O-R-T-Y.org, where you could also find videos, articles, and recommended readings.

Most conversations about teshuvah begin with doing teshuvah kind of reflecting on specific actions or behaviors that you can be better on, maybe treating people better, maybe taking Shabbos more seriously, finding some area or aspect of your life that needs improvement. I think for a lot of people and particularly a lot of people who may be listeners or part of the larger 18Forty community, sometimes what you grapple with is not any specific piece of your religious life or any specific component of Yiddishkeit, or what it means to be a part of the Jewish community, but it’s religious life itself.

It’s the entire entity, the entire edifice. And very rarely do we get to really listen in on somebody’s recommitment or commitment to Yiddishkeit itself, why they have decided to place religion, so to speak, at the center of their lives. It’s a different question in many ways than taking your religious life more seriously. It’s different than why you shouldn’t talk during davening. It’s different in a whole lot of ways than conversations related to improving your awe of God, yirat shamayim, or love of God, ahavat Hashem, or whatever language is used. It’s a more foundational language, and to me, it is at the heart of the teshuvah process, returning to religion, returning to Yiddishkeit itself. When you say even returning to religion, it almost sounds Christian. It’s not something that we oftentimes talk about. But I do think at the heart of teshuvah is really a question of placement and a question of motivation, of realizing where do you place your religious commitments in your larger life.

And so often we are tugged in so many other directions, our work life, our family life, all of the commitments that we have, and while we might do… In Hebrew, there’s a great word, I think it’s called shiputzim, which is like these little improvements — you put in a new kitchen, you redo your floor, you do another paint job. And that’s oftentimes the imagery that we think about when we think about the time of Elul leading up to the High Holidays, to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we think about doing these improvements. We’ve got to put in new plumbing, maybe resand the floor. I’m so bad with home improvements that my examples are going to be terrible and it will show. But we think very often of kind of these very important, but more micro-issues within our religious life. And for us, I understand why. By and large, for many of our listeners, we’re committed Jews, so why do we have to talk about the commitment itself?

We have a Jewish education, we show up to shul, so why talk about the entire edifice? But I do think there can be an annoying feeling in our religious life that we are missing that underlying reason of why we committed because the truth is, if we’re really honest with ourselves, most of us never committed in the first place, most of us were grown into this, we grew up into this. We didn’t make a decision to become Jewish. We didn’t make a decision to become religious. We were grown up into it, and once you’re grown up into it, as Jeff Bloom said in our conversation, in our series on rationalities, sometimes it becomes harder and harder to justify, or to kind of reflect back on those very commitments. The language we use very often is talking to the already initiated.

And sometimes you need to go outside the entire building in order to lift it up, in order to reawaken the very reasons for our commitment. And this past year, I read an essay that is not explicitly about teshuvah but in many ways is exactly what teshuvah is all about. It was an essay that was written by Antonio Garcia Martinez entitled, “Why Judaism? On abandoning secular modernity.” And today’s episode is really more than anything else about his essay. It is about why he wrote it and what it’s about because I’ve been reading quite a bit about Jewish life and Jewish law, and one of the most powerful essays I have read making the case for Jewish life is this essay by Antonio Garcia Martinez, “Why Judaism? On abandoning secular modernity,” where he essentially explains why he decided to convert to Judaism.

For those who are not familiar with Antonio Garcia Martinez, he’s a pretty major figure. Those may know him in the tech world. He’s a pretty serious person. He’s worked at Facebook and Apple, and he’s starting a company now called the Lincoln Network, which you can of course check out online and he’s doing some really, really amazing and remarkable work. But I want to talk about this essay that he wrote. And before we even get into the conversation, I want to begin by reading from the essay so you can have an understanding of what he is contending with and really understand his own journey to conversion into Judaism. The essay begins with a quote from Deuteronomy chapter 29, verse 13 and 14, otherwise known as Devarim, this is in the beginning of Parshat Nitzavim, which is really the entire parsha where we derive the very idea, the very notion of teshuvah. I’ll read it in Hebrew and then I’ll read his translation. And the Torah says, as follows, “V’lo itchem levadchem anochi koret et habrit hazot v’et ha’ala hazot ki et asher yeshno po imanu omed hayom lifnei Hashem elokenu v’et asher aineno po imanu hayom.”

His essay begins with the quote in English, “I make this covenant with its sanctions, not with you alone, but with those who are standing with us this day, and with those who are not with us here this day.” And this of course is the verse that we learned, that there were many standing at Sinai, so to speak the souls at Sinai, who were standing there and a part in the souls later on to convert, I’m not sure if that’s the reason why he started with that verse, but he begins remarkably with some fairly moving imagery, and this is how the essay begins. “You will watch your parents die and be buried. You will watch your newborn child emerge in a messy circus of having grunts and high-pitch wailing. You will watch your dreams and projects dashed only to wake the next day and greet the fruits of your failure anew and cobble a life out of them all the same.

“You will punctuate the cavalcade of events with moments of transcendent meaning that will linger in memory like fading signposts during the final moment, your death. Navigating that journey without a religious tradition is like trying to cross open country without a path: you can do so, but you’ll do lots of stumbling and very likely lose your way. Trying to get through dense woods — a serious depression, the death of a loved one — without a marked trail requires the most arduous labor for the merest progress. Furthermore, if you tackle these wilds in their raw and uncleared state, you will almost certainly do so alone. Going off trail means a hard, solitary journey, while the marked trail involves communal groups headed in your same direction. What some might describe as a cultural rut, some timeworn lane that limits movement, might just be the only thing that guides you through this daunting wilderness of life whose many paths all end in the same destination. To DIY…”, which means is an acronym for do it yourself.

“…Your own world life of life signifiers, you have to think you can improve on a bar mitzvah as a coming-of-age ritual, on Shabbat as a form of digital detox, and as teshuvah as a way to grapple with your guilt or analogs in other religious traditions. Many do of course, and every trendy San Franciscan has their personal regimen of special diets, meditation schedules, intermittent fasts, escapes to nature, a canon of mimetic culture usually drawn from their online feeds, a smattering of trendy texts that inform their values, and some slew of Netflix shows that serve as cultural touchpoints with others in their cohort.

“This is all in keeping with the current liberal project’s moral goal, which is creating lives devoid of any unchosen obligations and absolutely rife with chosen identities of fanciful and recent coinage. The problem is that it’s the unchosen obligations, or the obligations chosen but whose downstream responsibilities cannot be chosen, that will give us the only real meaning in life. Family, children, our hometowns, our childhoods, our ethnic identity if we have one, or the chosen but undoable commitments: marriage, joining the military, that company we start, religious faith, are the defining obligations where our selves really play out.

“If I were to go back and say one thing to my younger self, as a warning from the future, it’s this: The eventual cost of optionality in life, all of the commitments you don’t make to preserve your ability to instantly change course is usually not worth the upside that optionality eventually produces. And even when that optionality is rich indeed, and I know a thing or two about the exploding value of literal financial options, your commitment to that remunerative course, fully cognizant of your wider obligations will serve you better than the anxious FOMOing of the hyper-optimizer, which is the long way of saying that at some point you have to choose a hill to die on, because if you don’t, you won’t really ever have lived at all. Here I will attempt to lay out why you should also do so, and why I chose the Jewish hill that I did.” That is how he begins his essay on “Why Judaism?” And I began our conversation with Antonio Garcia Martinez asking him why on earth did he choose to write this essay?

So it is my absolute pleasure to introduce Antonio who really went… can I say viral? Like you went viral from this incredible essay about your choice to become Jewish.

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

And it’s a two-part essay. The first part really talks about rejecting… you almost retitled it in one of your footnotes saying, this is really an essay about why I didn’t pick modern liberalism. And then you have a second part, which is why specifically Judaism, fair enough?

Antonio García Martínez:

And yet, and just to clarify a little bit, it’s modern secular liberalism with a small L, it’s not liberal politics as it’s known in the U.S.

David Bashevkin:

Yes. Correct. So I was saying this to you just before. We know each other tangentially through Twitter, you’re always so kind. We don’t really have that much interactions. We don’t run in the same circles. When I read this essay you wrote, and I just reread it, I really mean this from the bottom of my heart, it stands in the Pantheon of defenses of religious life, religious commitment. I would put it in the same category as Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch, who was an articulate writer in the 19th century, wrote “The Nineteen Letters.” I would put in earlier defenses that were trying to make the case, what does religious life offer? And what I was hoping that we could start to talk about is what was your life before this? Why on earth did you decide to become Jewish? What did your life look at before you made this choice?

Antonio García Martínez:

Thank you for the introduction, David. I mean, you’ve so buttered my muffin that I have to go reread my work to see what was so great about it. Because it did… You’re right that it did go viral on what I affectionately called Twitter, I guess, Jewish Twitter.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

And I think one of the more interesting data points that came out of that I was at kinus, which is the Chabad thing last October.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Antonio García Martínez:

And I was there with Mottel on Twitter, Mordechai Lightstone, who’s like their head of social media.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. Mottel.

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah. Mottel. Yeah. Yeah. He’s a great guy. And I was randomly talking to one of the rabbis there and I mentioned my name, and he’s like, wait, are you that guy? And then Chabad rabbi, the full Haredi thing. He whips at his phone. He goes to his Chabad rabbi WhatsApp group, and there’s my piece after reading and I was like, oh my God.

David Bashevkin:

It’s not a joke because there is an issue nowadays where making the case for religious life and religious commitment is so intertwined with the human experience, and the human experience changes. So the case changes along with it and evolves with it. And what’s so interesting is that you make the case by couching it in kind of something so much more stable. But the ability to make the case requires a resilience and a development and evolution of being in touch with contemporary life. But I think a lot of rabbis, myself included really struggle with, why is this meaningful? Why does this even matter? We don’t understand the secular world. I was born into this. So I didn’t have the language to make the case you did. And maybe we could start with what was the life that you were born into and were living before you came to this realization.

Antonio García Martínez:

Sure. As the name implies, not a terribly Jewish name, although I guess there’s probably, there might be some Sefardim who have.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Antonio García Martínez:

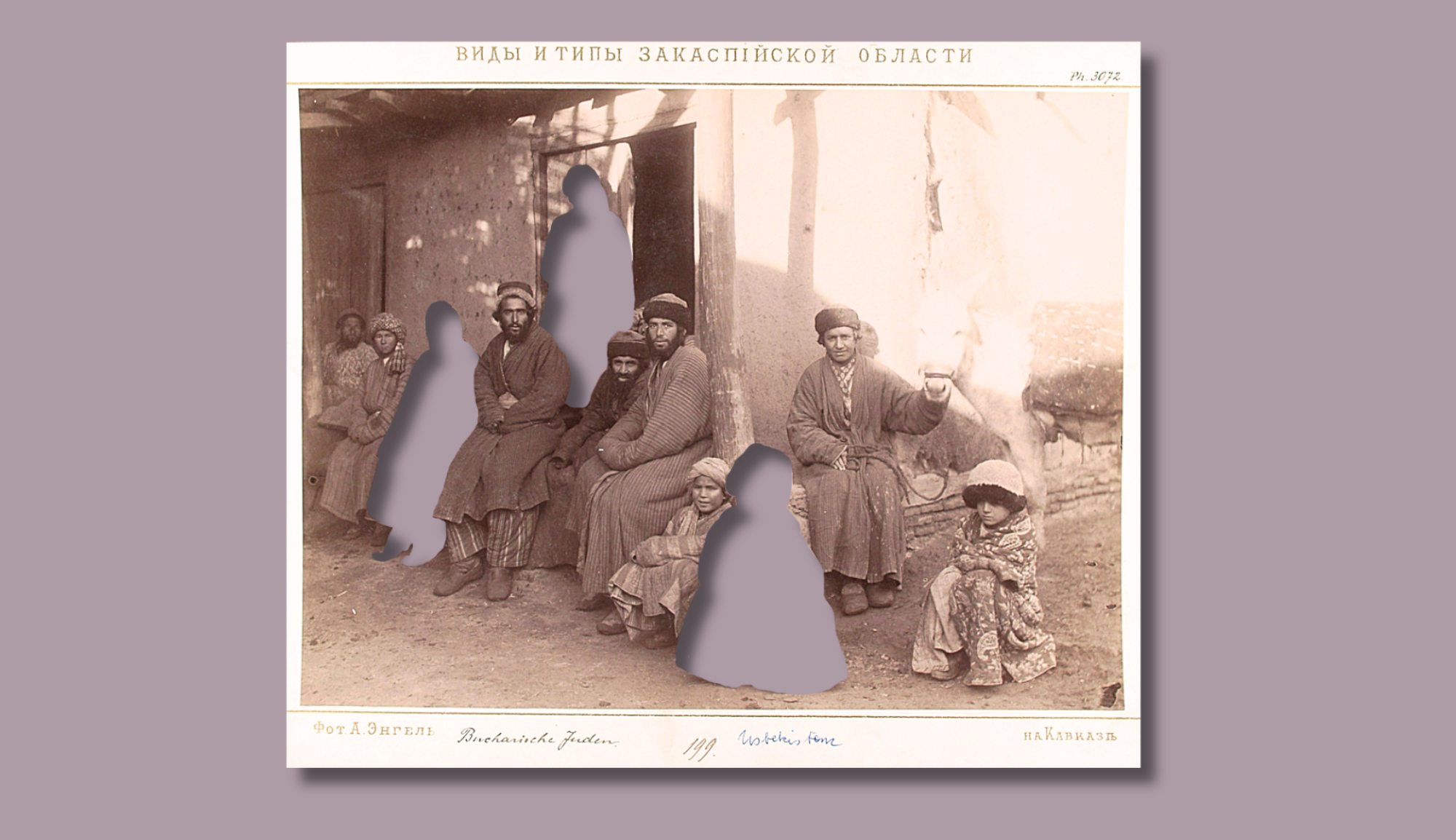

I have met Sefardim who have Martinez actually. Yeah, so people ask you where you’re from. And in my case, it’s always a long parenthetical footnote. So in my case, I’m a Spanish citizen officially also an American citizen, because I was born in the U.S., but my grandparents and great-grandparents were Spanish immigrants to Cuba in the early part of the 20th century, which might sound sort of incongruent now. But at one point in time, Cuba was worth immigrating to, in fact, had a large Jewish population. There’s a number of synagogues left in Havana.

David Bashevkin:

Sure, absolutely.

Antonio García Martínez:

Almost all of them left to Miami and actually founded some of the synagogues that are still in Miami in fact. In any case, they fled after the revolution, I was born in the U.S. and then raised in Miami. And then I’m speaking to you from San Francisco and I’ve been kind of in and out of the tech and media worlds for the past 15 plus years. Raised Catholic, but the Cubans weren’t that Catholic, I went to a Jesuit school, which tends to be a very kind of hyper-intellectual flavor of Catholicism.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Antonio García Martínez:

But there was masses in the liturgical calendar and all that stuff. And my first reading of the Torah was as the Old Testament in a Catholic translation and the Jesuits, of course, insisted on reading the most annotated and academic one with the footnotes that take up half the page type of thing. So that was my introduction to the sort of Jewish story. And so, Hebrew, Jewish presence wasn’t exactly absent in my life. Also Miami nowadays is probably one of the Jewy-ish cities maybe after New York or something.

David Bashevkin:

Oh yeah. Oh yeah. It’s like Yerushalayim, Israel, New York. Miami is definitely…

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah, which sounds unusual. A lot of people associate Florida with beaches and Disneyland, and it’s really, Miami is really a whole different world. And you’ll see people walking around in kippahs and no one even blinks. It’s just…

David Bashevkin:

Oh, I feel like you could fast-track them to conversions and be like, I lived in Miami for 10 years like, oh, you get it.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

You understand what this is

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

So what was going on in your life? There’s something very abrupt, there’s something deeply holy about a conversion process. I’ve written quite a bit about the theology of converting and how so much of Jewish history was built through converts. This really strange interplay between converts and kohanim, which is the more insular, that’s the lineage that traces all the way back. But I’m curious what was going on in your life that you decided to make a change like this?

Antonio García Martínez:

I mean, as I say in my piece, one of my objections to sort of secular liberalism, is that — not everywhere of course and obviously if you’re in San Francisco and New York you’re seeing one part of the American experience — but it seems to be the case that we’ve gotten to a point where the only functioning organization most Americans see is a corporation or a company. Particularly in places like San Francisco, where it’s all tech and this and that and then everything else is kind of in various states of falling apart to some degree or another. And then of course all the various swirling moral and political dramas that are now happening in our secular liberal state. I don’t want to just sit here and turn into a woke thing, but a lot of this, what I would consider to be almost Protestant.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

Post-Christian sort of pseudo-religion has taken over the public space in a way and has become the bulk of the conversation. So I find it personally interesting and fulfilling.

David Bashevkin:

But let me ask you, I’m curious, was it a moment where you decided I want to join the Jewish people or was it a slow, percolated, like the crockpot? Jews loves to cook in the crockpot, especially on Shabbos.

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

How did you come to it? Meaning, okay, it’s interesting. It’s intriguing. But why formalize it?

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah. Well, I guess some rabbis think that the convert potentially was born with the Jewish soul. And so you might want to retrospectively look at, are there points that Judaism intersect in my trajectory before this moment? Possibly. It might be a weird parallel to draw, although it might be less so for Miami people. The Cuban exiles in Miami, for purely parallel reasons, although there are lots of Cuban Jews, Jubans, as they’re known by the way. And ironically, I never heard that term, but it’s actually a thing.

They also toast on events, “Next year in Havana,” almost like you do in–

David Bashevkin:

Wow.

Antonio García Martínez:

And it’s the same feeling of feeling destituted from some often idealized past frankly.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

And then the sort of dissatisfactory reality. Of course, with the state of Israel it’s not quite the case with Jews anymore. They can actually go to Jerusalem.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

Well, in Miami, I mean you can travel to Havana, but you generally don’t want to. But they still have this feeling of loss, and it’s this weird neurotic feeling of insecurity as a minority in this country, but also a mild feeling, I wouldn’t say of superiority, but something needs to be maintained. If you go to Miami, they’ve basically rebooted what was prerevolutionary Cuba in a suburban American environment, like I went to the same high school Fidel Castro went to. The Jesuits got kicked out, they reestablished the exact same institutions in Miami, and what you’re seeing is kind of like a reboot of it. And so they have this nostalgic sense of maintaining something.

David Bashevkin:

I want to come back and read where the essay goes, because I think it’s so important to understanding contemporary religious life. This is how Antonio Martinez Garcia continues, “Every society needs a metaphysics that allows it to have moral and political conversations with itself. Liberalisms preferred metaphysical framework of utilitarianism — in effect, ethics by Excel spreadsheet — is at best a simplistic hack that illuminates some tradeoff, much as microeconomics can inform the pricing of Starbucks’s various coffee sizes. That’s assuming society could even do the hard math of exchanging one type of human wellbeing (or even entire lives) against others in a rational way. It’s more than a little pathetic watching an avowedly atheist materialist society whose epistemology ends at empiricism play at metaphysics. It makes them suck even at empiricism, as a reality must be warped to suit whatever non-empirical argument they’re incapable of expressing any other way.”

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah. The key thing about Judaism to me is that in some sense, you can avoid the question. And again by the way, I was a science guy, I had bailed on a PhD in physics, but I spent-

David Bashevkin:

That’s clear in your piece that you are a science guy.

Antonio García Martínez:

But I’ve spent years, I’m as rationalist and materialist and empirical as anyone could possibly get. But precisely because of that, the reality is that you need a metaphysics of some sort, and metaphysics just means some form of reasoning beyond the purely empirical and material. Because the problem is if a society doesn’t have a metaphysics, it’s going to suck even at empiricism, right? Because at the end of the day, there’s a lot of questions that we ask ourselves. In fact, I would say most of the questions we ask ourselves, that are not answerable in a science lab or a mathematical equation. As good as those things are getting other answers to questions, they’re not going to answer what is good in life? To what should we actually dedicate our resources? What is a fulfilled life? Science is never going to ask any of it.

David Bashevkin:

You’re left with an empty Holy of Holies that needs to be filled.

Antonio García Martínez:

Somehow. And the great thing about Judaism is that it fills it. It doesn’t… Like you can believe or not that God has stopped acting in the world. Maybe the state of Israel was God acting in the world or the miracle of the ’67 war, but it doesn’t matter. In some sense, you have to fill that holy space with something and you can’t not fill it, even the seculars have Gods in there. And I would just say that there’s never no religion. There’s only bad religion and there’s good religion. And if you have to pick one, although I wasn’t quite as utilitarian about it as that, I think Judaism does very well with modernity. Unlike other religions, that modernity represents a threat that must be repressed. I think Judaism, I mean by its very nature over the thousands of years of history and 2000 years of exile, has adapted itself very well to circumstances. While at the same time, maintaining true to a vision that’s lasted longer than many other ones and it’s an interesting duality that you see.

David Bashevkin:

Well, I think at the heart of your article and what resonated most with me, and we have an interview that we’re going to be playing as a part of this episode, which is an Orthodox Jew who reached out to you, who had lapsed his own faith in the community. And I reached out to him personally to say what resonated so much? And at the heart of what he said and at the heart of what I found was the way you speak about optionality. Optionality is that you grow up and you think the number one best thing you can have are options. You want options in your career, in your identity, in your path in front of you. And what you basically make a case for is that maybe optionality is not the end-all be-all of what it’s cracked up to be.

Antonio García Martínez:

I mean, yeah. And I say this as someone who’s been guilty of this too long in my own life, to be clear, I learned this the hard way, which is by making the mistake for too many years.

David Bashevkin:

How did you make this mistake?

Antonio García Martínez:

Well, because… I don’t know, it might get a little bit too therapeutic and me-centric, but…

David Bashevkin:

Let’s get therapeutic and me-centric. Let’s do it. Let’s do it.

Antonio García Martínez:

I mean, at a high level, I think I have a line in there somewhere and I probably borrowed this from Rod Dreher, to be honest, when I come think about it.

David Bashevkin:

From who’d you borrow it from?

Antonio García Martínez:

Rod Dreher.

David Bashevkin:

I don’t know who that is.

Antonio García Martínez:

He’s a conservative Christian, he’s an Orthodox Christian actually.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Antonio García Martínez:

You’ve probably heard of his books. He wrote “The Benedict Option.”

David Bashevkin:

Okay. Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

Which argued for Christians kind of retiring from the public space and he is written a number of other books and he’s a major name in right-wing, religious-tinged American thought.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Antonio García Martínez:

And I’ve interviewed him and we’ve had a number of debates about… We don’t agree about a lot of things to be honest. But I think he said originally liberalism is the project to liberate the individual from any unchosen obligation.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

That is the quest of liberalism. And it’s funny that because all the happiness and meaning you’re going to find in life is in fact not opting out of obligations. It’s in fact, getting stuck with obligations like a religion, or a tradition, or an identity, or children, and saying actually, yeah I can’t back out actually, I’ve got to make do with what this is. And again, I think it’s antithetical to a lot of thinking that often tends to be very independent-minded, frankly a little hedonistic, a little selfish. And so even though in my case, I’m choosing this obligation, and again, there are obligations worth choosing, choosing to get married, choosing to join the military, choosing to dedicate your life to a cause. I mean those are chosen, but once they’re chosen, it’s hard to kind of unchoose them is the thing, right?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

You can’t just walk away from Judaism or the military or a kid. You sort of can’t. And so I think, again, it’s odd that society has said the goal for all of human striving should be the independence from obligations and yet happiness, or at least the feeling of meaning — happiness is too vague a term for me to think about — is often in a very different direction, so that’s what I meant by it.

David Bashevkin:

Antonio ends the first part of his essay by reflecting on Simchat Torah and a Simchat Torah experience that he had. And he writes: “when Jews take the Torah scrolls out of the synagogue’s ark and joyfully parade them outdoors, dancing and singing with their scripture’s heavy burden slung awkwardly on their shoulders. It marks the end of the annual cycle wherein an advancing Torah portion is read aloud every sabbath, one turn of the scroll at a time until the very end. It is the one Jewish festival not divinely ordained nor the product of some historical event; this the Jews put on for themselves in their obsessive love for their collective story. And when all the singing and dancing is over, they immediately rewind the scroll and start reading again, as they have for millennia: ‘In the beginning God created heaven and Earth…’

“As that scroll is returned to the ark after the reading, the gathered crowd recites: ‘It is a tree of life to those who hold fast to it.’ Indeed it has been a tree of life to a people who made it the foundation of their civilization, a people that stubbornly persisted in a world that often wanted nothing less than their total extermination; a world that even now begrudges the Jews the tiny state they perilously safeguard. Stuck in a secular modernity that’s lost the plot, and that no longer knows what it is or where it’s going, I choose to hold fast to that tree of life. I also say, as the loyal convert Ruth once said to Naomi: “Wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there will I be buried.”

Now, Antonio Garcia Martinez’s essay, as we discuss later, is really in two parts. He cleverly or sweetly calls the second part, “Why Judaism? Part Sheni,” the second part, of course, in Hebrew, on the question of God in modernity. And in there, he kind of responds more specifically to why Judaism and the response of so many of his secular colleagues and friends who are like, are you serious? Do you actually believe in God? That sounds insane. And his consideration of God, while not traditional, is actually quite powerful. Let’s return back to the essay and hear about how this PhD dropout thinks about God.

“My intuitive take on all of this,” he writes, “is that if there is a God operating in the physical universe we see, it must be such a transcendent force so beyond our limited human experience, we’d never be able to ‘prove’ anything about it … at least not for a very, very long time of mental, technical and cultural evolution. All of our ancestors were banging rocks together on open plains as hunter-gatherer bands not more than a few thousand years ago. To quote Vonnegut: ‘Just because some of us can read and write and do a little math, that doesn’t mean we deserve to conquer the Universe.’”

I’m skipping a little bit, but he writes as follows: “I find it more than a little cheeky when a species of hairless apes that figured out antibiotics and genes and the full implications of relativity only a few decades ago suddenly declares ‘Yup, we know everything about the origins of this immense universe, despite barely having stepped foot off our rock.’ And by the way, in addition to claiming to have figured out the intricate clockwork of the universe with our big brains, our brilliant species still flips out like chimpanzees over optical illusions such as the ones my five-year-old loves. I think we’re a little high on our own supply here; a certain amount of epistemic humility and understanding of just how little we understand should push us toward less dispositive conclusions about the true nature of the universe.

“The truly materialist anti-anthropocentric view here would be skeptical of the reasoning abilities of a species whose major issue right now seems to be its addiction to the blinking lights of a thing called Facebook. To discard any notion of God in the universe, you have to enthrone humans and their grand intelligence in that role instead, and I think the throne is a bit too big for us at the moment.

“Sure, the ‘man in the sky’ vision of God is silly, and no doubt some credulous believers have that conception in their heads, but it’s a lame atheist counter-argument when you attack only the weakest versions of your opponent’s arguments. It’s a rather different matter to take on (say) physicist Paul Davies and his various ruminations on how the universe is arranged such that we can even sit around and ask these questions (just to cite one example of science-inspired metaphysical speculation). ‘The man in the sky’ is easy to debunk; why the fine-structure constant is 1/137, just the right value to make physics and biology work, is a harder nut to crack.

“Ultimately, at our level of technology, God is no more true or false than ‘democracy’ or FICO scores or oil futures, and look how many humans run around like agitated ants because of those concepts. Intangible things become real when enough humans act like they’re real. In our species’ feverish drive to imbue symbols of our own devising with as much reality as a pouncing tiger (and often generating as much emotion), asking if those abstractions really ‘exist’ amounts to little more than philosophical repartee.

“I’ll (once again) draw on a hopefully illuminating example from the Jewish world: Judaism has had two temples, the first a somewhat legendary one involving David and Solomon, and a more recent one of very historical reality which the Romans destroyed in 70 AD (you can see the violent shenanigans in the Arch of Titus in Rome to this day).

“At the center of the Second Temple was the so-called Holy of Holies, the holiest site of Judaism even now (though where it sits on the Temple Mount is still debated). That space, toward which every Jew then and now prays … was empty. The Ark of the Covenant of Indiana Jones fame (which stood in the First Temple) had long ago been lost during the Babylonian exile. The sanctuary had a bare dais, a sort of negative-space symbol for the ark, and not much else.

“Secular modernity stands like the Second Temple, with an empty room at its center. The relics of God’s direct involvement on Earth in the form of the Mosaic tablets, if they ever existed, are long gone. The last prophets who served as mouthpieces of God, whether they were even real prophets or not, were centuries ago and exist now only in ancient cautionary texts. It is up to us to symbolically fill that space with something worth our devotion and praise.

“Nihilism, true existential nihilism, is something most of us can’t really live with for any length of time. Do it long enough, and you’ll end up like me strung out on SSRIs and benzos for months until you find some way out of it, assuming you ever do. In reality, we all populate that sanctuary with something; none of us has an empty Holy of Holies.”

And I found that imagery so incredibly moving and I asked him about it.

Why did you write this essay, meaning, it sounded like you were trying to justify yourself almost to either an unspoken voice or to yourself or to communal reactions. You do write a lot, you are a writer, who was the audience who you were writing to?

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah, what did spur this? I remember I wrote it in kind of the heat of a moment type thing. It didn’t take very long, although it’s not very short, and it usually takes me a while to turn around a piece. I’m not like a cultural warrior online, I don’t take sides in it, but this whole wokeness thing and constant crusades over new and new things that we must pursue, it kind of woke me up that there is some sort of, I think I say in the piece, there’s a God-shaped hole at the heart of much of liberalism.

David Bashevkin:

That imagery, I’ll just say, it’s amazing imagery, which is true. Josephus writes about this in his book, that when Titus came to the Holy of Holies and conquered the temple, he was actually shocked because he went into the Holy of Holies and expected to see something magnificent, maybe the Ark of the Covenant, what we’re used to seeing in Indiana Jones, and it was an empty space. And I knew that because of my Talmudic knowledge. But I remember when I first read that in Josephus and how shocking it was to read Titus’s shock, that imagery was deeply moving and you use that imagery to describe what?

Antonio García Martínez:

Right. That in some sense, the core of the secular liberal temple is kind of empty. And even if you do or don’t believe in God, and I get into this more in the second essay, I guess, because-

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Antonio García Martínez:

That was originally this part, because I’ve had this debate with several people who are very much in the secular rationalist mold.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

And even though they have lots of beliefs that I would characterize as kind of religious or definitely metaphysical, whenever I mention the Jewish things, “why are you doing this? Do you believe in God?” And again, it’s weird to debate, particularly Judaism. There’s a lot of things common in the Judeo-Christian tradition speaking broadly, but there are a lot of things that are actually very different, and it’s the differences that are interesting. And so obviously on the Christian side, your personal relationship, your faith-based belief in Jesus who comes and saves you. And different Christian sects have different levels of this. Catholicism, I would say, has a little bit less than that, but it’s still an important part of it. You can’t be a Christian and not believe in God, and that Christ was a son of God, and that they’re there to redeem your sins and all, you can’t be a Christian and not believe that.

David Bashevkin:

That imagery from the Second Temple and that we all have an empty Holy of Holies, and the question is what are we going to fill it with is something that I found so incredibly moving and so incredibly true. And it’s there that I asked him, what exactly is he doing teshuvah for, so to speak. And what always struck me so strange is that a scientist, he’s a dropout as he mentions from a PhD in physics, what draws him to the ritual life of Jewish life which is so heavy on ritual? How is that something that even speaks to him? And it was to these questions that I was so incredibly moved, and this is our discussion.

I’m curious in your own self-conception, if I were to ask you, what did you do teshuvah for, what would you say?

Antonio García Martínez:

Well, I think that the secular… By the way, I’m a fan of liberalism by and large, just to be clear. All these post-liberals, like these new right people that I’ve written a little bit about, I tend to reject and I think that they’re all kind of LARPing, so just to be clear, I’m not rejecting what we would call secular liberal life.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Tell our listeners what LARPing is just for our-

Antonio García Martínez:

Sorry.

David Bashevkin:

I usually ask our interviewees to translate their Hebrew and Yiddish terminology, but this is different kind. Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah, Twitter terminology is even more esoteric and weird than Yiddish.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

So LARPing refers to, strictly speaking, live action role play. And that’s like the Renaissance fair people or the Civil War reenactor people who, again, nothing against it. It seems like a fun activity, you dress up as a thing and you behave like a thing. But in the extreme version of that, the negative connotation to it is like, well, it’s great that you’re play acting and being in the Renaissance, but if you were actually in the horribly violent and hard life of the Renaissance, you would be one of the first people to go because you actually can’t. So when someone’s accused of being a LARPer, what it means is, yeah you’re kind of play acting at that thing in the same way that many people look towards some theocratic or post-liberal reality, but it’s like actually if we rewound and took you to 16th century Europe, you’d be the first to be like, “Get me the hell out of here,” and so that’s what it means by LARPing. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. So you were saying your act of teshuvah was moving away because you’re saying you have no issue with liberalism, but this kind of secular… Finish that thought. Finish that thought for me.

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah. It feels kind of very empty, and again, nothing against it necessarily. I don’t mean for it to be a negative thing, but people who follow all this keto stuff, and it’s like there’s a level of complexity and weird sort of religiosity around it that is comparable to anything in kashrut and nothing against going to Burning Man, but it’s almost like a hajj, right?

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

It’s like a hajj for hipsters that they go off into the desert, which I think is a good thing to do by the way. I’ve actually gone to Black Rock desert, not during Burning Man, but when there’s no one there, and it’s an amazing thing to go out in the desert and kind of experience the nothingness of it. But it just seems odd to me that again, nobody can actually live life staring into the abyss, say for people who have been horribly clinically depressed — which I have in the past, by the way — or people who are addicted to drugs, which I’ve not been in the past, I don’t think so.

So people who actually sit staring at the abyss, I think it’s impossible. A lot of these new atheists, they’re now known almost nobody talks about them anymore, because I think the project was kind of a failure. But you’re left with very little at the end of the day. guess the modern embodiment of new atheists are the effective altruists, which is another online community.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

For those who aren’t familiar, what it means, it’s kind of tied to the rationalist community, although it’s somewhat different. It’s not a terrible idea, conceptually, the thought is to apply the same utilitarianism, and that just means the sort of Bentham-esque… like it’s ethics by Excel spreadsheet.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Antonio García Martínez:

Here are the positives of this plan, here are the negatives.

David Bashevkin:

Cost, benefits…

Antonio García Martínez:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

Spread it out.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right. You tabulate the hedons, or whatever Bentham called them, and whatever plan wins that’s the ultimate good. And usually in the world of ethics, this is contrasted to what’s known as deontology, which is basically a rules-based system, which is Judaism by the way, which is like, here’s literally the tablet of the 10 things you got to do and we’re not trading off anything, this is just what it is, and we consider this to be the good and we’ll craft a society around these principles. But the problem with utilitarianism and liberalism in general is like, well, I mean that does work at the micro scale, but if you’re trading off, I don’t know, housing policy in some market, it probably makes sense to do it that way rather than some theology of something.

And you get this in a philosophy 101 course that you take on utilitarianism. It’s like, well, what if we kill a newborn and harvest their organs and save seven people? Well, the math kind of works out, which sounds insane, but the math works out. Or the classic argument against is also like, but in the utilitarian mind, you would actually prefer a world of a hundred billion people, barely above the poverty line rather than a world of seven billion people in which many live above the poverty line, because at the end of the day you get more. And these seem like an absurd reduction, but you can see where the problem lies, which is, you need the infinities on the spreadsheet. Because at the end of the day, the real moral issues that we struggle around and just to pick something non-controversial, is abortion moral? You can’t do math and get the answer to that. At the end of the day, someone’s going to invoke some moral infinity, and that is the conversation that’s worth having. Where do you get those moral infinities from?

David Bashevkin:

So I’m curious about your highly scientific that comes out in your second essay even more, your first essay is almost more political thought.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

But your second essay is highly scientific. I am curious about what role the ritual is able to play in your life. You have ritual and it focuses on these little itty bitty details. Not all of our listeners, many of our listeners are Orthodox.

Antonio García Martínez:

Got it.

David Bashevkin:

So, I insisted and wanted to have you because you have such a fresh perspective on what so many others take for granted. I’m curious what the transition into a world of ritual has meant for you, if at all, or did you transition and became this folk hero within the Jewish community and now you’ve converted and you’re like, oh dear God, we’re doing this every week?

Antonio García Martínez:

I think the ritual is interesting. Again, I would claim that’s the big divide between Christianity and Judaism, and there’s a lot of places where I think the traditions overlap. But making the mundane sacred, in some sense, or what can often seem the everyday sacred is one of the unique things about Judaism. And I think you do need to have feelings of transcendence. You need to have these luminous moments of beauty and clarity. You can call it God, and if you’re a secular, you wouldn’t call it God, you’d call it something else, but at the end of the day, you’d be grasping at the same topic. And I think God’s just a better word for it because it’s just like, it’s just shorter, I guess.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, sure. One syllable.

Antonio García Martínez:

Although if I was Orthodox, I wouldn’t even be saying it. But yeah, it’s one syllable you can say at this transcendent something that you feel is the good in the world. And again, I often quote William James that at its core religious feeling is the thought that there’s some sort of moral order to which human life should aspire.

David Bashevkin:

Yes, there’s a unity underlying the world.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right. And so then how do you repeat the magic? So a secular could go to Yosemite and hike Yosemite and look at Half Dome and feel it, but that’s hard to do every Friday in the city. And so you need to have some sort of repetitive association, you do the thing to produce an emotion, and then when you feel the emotion you do the thing. And I think that’s part of the very obvious association that you do through the Jewish liturgy, whether it be lighting the Shabbat candles or going for the High Holidays or whatever. That’s the thing that religion is basically transcendent as a service, to use a very core software analogy. You often have software as a service, or delivery as a service, it’s a feeling of transcendence and Godness as a service. And then again, I think it’s hard to access that in any real way as a secular person. I mean, you can see it in your kids, people clearly are having a religion experience with their children.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

But again, it’s hard to produce that, and also it’s hard to produce that in a communal setting cause people live very atomized lives now. I often ask myself if Americans had to sing one song that they could just inarguably sing together and feel a feeling of closeness, not even the national anthem would qualify these days probably, while obviously on the Jewish side much of the Jewish liturgy is sung, and that happens all the time.

David Bashevkin:

To me, whenever I think… and we did a series on halacha I used almost the exact same analogy. I didn’t use the word produce, I used the word preserve and I would almost use a similar software analogy and to scale, meaning what’s so difficult… to produce this you don’t need religion, to feel it once like you said to go to Yosemite. To preserve a divine idea, integrated as part of the routine, almost the mindlessness of the transcendent, that it just becomes a routine in your everyday life, and then to scale it out among multiple families, multiple people that you’re part of a community is really where the magic of Jewish law, halacha, comes out. I’m curious for you, have you developed a favorite aspect of Jewish life?

Antonio García Martínez:

Right now, so I just started a company and I’m like in startup life. So the fact that I’m observing Shabbat and not checking Twitter and email on Shabbat is pretty incredible, I have to say. It’s great to have a divinely ordained reason to not look at Twitter or not check email. And it also imposes a regular weekly cadence, all the good things that all Jews know about Shabbat.

David Bashevkin:

My final question that I asked him about was really just understanding what is the background? What is the world that you were looking at that drew you to this religious world that you so eloquently described in your essays? And his answer was kind of that fish in water that we don’t appreciate the world that ultimately surrounds us. Here’s the continuation of our conversation.

Is there something at the heart that’s animating people’s thought that will allow them to better appreciate this decision that you made, aside from your essay which does it so eloquently, but your essay is more like frontal, it’s really saying what the decision was. I’m curious if there’s a step before, a book before, an idea before, that can lead you to that understanding of what secular liberalism optionality, what it does and does not get you.

Antonio García Martínez:

I think it’s just living in our current moment. The West, broadly speaking, seems so lost to me. And a lot of this might be childhood nostalgia, but I was a child of the eighties. The Cold War was going on. My parents had fled Communism. It just felt like there was a level of national unity and sense of purpose to the West. There’s a great enemy, which among Cubans, the fact that your country could lose and end up on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain were a very real thing in their heads, it wasn’t a theoretical possibility. There would seem to be an animating sense of purpose, and it seems like the West has somehow lost that. And I just see a lot of people around me that kind of lost in secularism. So it’s no particular book that made me say, oh, Judaism. It’s hard to navigate a society or have meaningful relationships or a meaningful life without either core foundational moral principles, and a shared tradition of some sort.

The ability to sing a song together in a group of people may sound very trivial and almost frivolous, but actually it’s not. If you can’t engage in that level of collective fellowship, something is going to be wrong with you and your life, and you need to find a way out of that. And again, I think Judaism is very good at that. It’s funny that people often contrast Judaism, oh, look at these weird Orthodox people with their funny clothes or look at the kippah or whatever, it’s like you realize Judaism has reconciled itself to modernity, I think much more healthily than, not to pick teams here, but a lot of other religions that cling to religion as an alternative to the reality. And one thing I should note is that Jews, at least seems to me, don’t recoil from the realities of life. They accommodate it. Literally just yesterday I bought a monitor from B&H Photo in New York, which for those who aren’t familiar with it, it’s like the biggest camera electronics you’ve ever seen in your entire life, and it’s owned by the Orthodox…

David Bashevkin:

Not just the Orthodox, it’s run by Hasidic Jews.

Antonio García Martínez:

Hasidic Jews, right. And if you go to their website, when it’s Shabbat, New York time, I think the website doesn’t even load.

David Bashevkin:

Yep. It says like, I’m sorry…

Antonio García Martínez:

It sounds… Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

It just says come back after Shabbos.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right. Well, and then it offers you to send you an email when they open again so you can actually order it because they don’t want to mess up the sale they just can’t take it during Shabbat. And these people sell the best electronic equipment, the best camera lenses, it’s like one of the best shops online, and yet they maintain this very traditional mindset. So yeah, I think that conflict in my opinion, is less pronounced inside Judaism than it is inside other religions. Also just to be clear, I’m like a total book nerd. My mother was a librarian, I was raised in a library. The thought that, in some sense, not quite worship the word exactly, but you find transcendence and meaning through the written word in the text. I have a passage in there about Simchat Torah… Oh, because Simchat Torah was I think happened right when I was writing that essay.

David Bashevkin:

Simchat Torah. Yes. Sure. It’s beautiful.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right. At the shul we did the whole thing, at least the Conservative version of it of lifting the Torah and re-rolling it and parading with it, and the whole thing. The fact that you would take such joy in literally just the written word is to my book-loving mind, you can see… my books behind me-

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Antonio García Martínez:

Is something I can get behind, I guess to put it that way.

David Bashevkin:

Before we get to the concluding questions from Antonio, there’s a remarkable postscript to this story. In mid-July, Antonio shared, anonymously, didn’t share the name, but he shared an email that he received from a formerly Orthodox Jew who had read his essays. And the email said as follows, “Hi Antonio. I want to thank you for your wonderful writings on your substack, in particular, your ‘Why Judaism’ post. I originally heard about you from your appearance on the “Eureka” podcast, which had been sent to me by a friend who I thought would be relevant to me. Both that episode and your post on ‘Why Judaism’ have influenced me significantly recently, and have changed the way I’m planning on living the rest of my life. Like you I’m Jewish, I’m a recent college graduate and attempting to assemble long-term plans that have been very difficult for me. I was raised as an Orthodox Jew, although I became an atheist during high school and stopped practicing in college.

“Now that I finished college, my religious family has been pressuring me into getting married, settling down and having kids, which is obviously very different than the typical path of secular college graduates these days. Looking at those around me, I had noticed that I much preferred the end result of the Orthodox Jewish families caring for and respecting their elders, having large families that actually like each other, unlike the stereotype of hating your family, et cetera, to the end result of secular families. But I’ve had trouble justifying how I can practice Orthodoxy, marry someone Orthodox, and most importantly, raise Orthodox kids, since I don’t believe in its objective truth myself. Your essay on ‘Why Judaism’ has truly opened my eyes and helped me quantify why some form of an Orthodox lifestyle is right for me and will lead me to a much happier outcome.

“I want to thank you for opening my eyes as to why it’s the right path for me. And I’m sure my family is also very grateful to you for the guidance you provided to me, even if they don’t know it yet. I have a family trip to Israel planned in a few weeks and I’m hoping that my time in our holy land will help cultivate my planned religious endeavors. My past few trips have been mostly devoid of religious significance, but I’m hoping that this one will be different. As I’m sure you’re aware, the day of mourning known as Tisha B’Av coming up, and it will be one of the first days of my trip. Being at the site of the destroyed temple on this day, obviously holds significance and I’m actually looking forward to the atmosphere of mourning that it will bring for once, in the hope of being able to join in. I apologize for this wall of text, I’ve tried to break it down a little bit to make it more readable. Thank you again for your writings, and thank you for taking the time to read this.”

I was so moved by this email and Antonio was kind enough to connect me with the person who wrote this email to tell us a little bit about his story and what brought him to email Antonio. And this is my conversation with the anonymous email respondent to Antonio’s essay.

I guess you could start, what was your upbringing like religiously? What kind of education did you have?

Ari:

My family is Chabad, so Orthodox. And the schools I went to were I’d say, well, elementary, middle school is modern Orthodox. My high school was pretty Orthodox, technically it’s a mesivta, not really a high school, but…

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Ari:

Potato potato. My upbringing was definitely Orthodox, and then I started becoming a little bit less religious in high school, not outwardly, of course, because mesivta. And then after high school or after mesivta, I went off to college, which was not typical. Most people would go to yeshiva for, I mean a year, multiple years, how ever long. And then, yeah, I went to college kind of messed around there a little bit. Didn’t really take it so seriously. I don’t think I had very good study habits from my years in mesivta. Yeah, eventually finished college and that’s where I am now, I suppose.

David Bashevkin:

And at what point did you say that you were, like in the email you had written that you basically identified as an atheist. At what age did you say that you kind of moved away from the upbringing that you had?

Ari:

I would say in 10th grade. Yeah. 15, 16 was when I started going what they call “off the derech,” I mean becoming less religious.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Ari:

But that was again, not publicly, kind of just privately. And then when I went off to college then publicly also.

David Bashevkin:

How would you characterize why you went off?

Ari:

It was for intellectual reasons. I didn’t agree with, and honestly, I still don’t agree with most of the teachings of it. I don’t agree in its objective truth basically.

David Bashevkin:

So tell me a little bit, how did you come across this essay and what did it do for you?

Ari:

Right, so I originally heard about this essay from a podcast called “Eureka.” Antonio was a guest on there and they discussed his essay and some other topics. That was sent to me by a friend who thought that I’d find it interesting, which I definitely did. So then after listening to the podcast, I looked up the essay and I read it and it kind of sat in the back of my mind for a while. I’d come back once in a while and read it, and then eventually I think it started to influence me a little bit and kind of made me decide to change my life path. And then I was kind of thinking about it one night, laying in bed, not able to sleep. And I decided to send Antonio an email just to let him know how much it impacted me. I figured he might want to know.

David Bashevkin:

It was a very moving email. I’m curious if you could share a little bit more about what exactly resonated with you. You yourself said that it’s not like a neat story where you read an essay and you’re like, oh, I see the truth, let me come all the way back, let me slap on a black hat and go back to my mesivta years, which is really what attracted me to the email, it was clear to me there. What were the ideas in the essay that resonated with you?

Ari:

So it’s worth keeping in mind I wrote this email kind of spur of the moment, middle of the night laying in bed.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Ari:

It might be a little bit messy, but yeah, there were a couple different things about his essay that really impacted me. I think he talks a bit about optionality, or basically keeping your options open, not really committing to a position because then it kind of closes other doors, it prevents you from switching that option in the future. People like to keep their options open, which he goes kind of in depth on to why he thinks it’s not a very good thing and how it’s a big part of, I guess, modern day liberalism to keep your options open. And I think hearing about his experience and how he kind of regrets the mistakes, some of what he thinks are mistakes he made back in the day, by not committing to a position and instead trying to keep all his doors open, how that negatively impacted his life.

He talks about a bit on the podcast I believe, he has a friend he mentions who lived a similar life in the sense that they had similar jobs and lived in similar places. But his friend, instead of Antonio, he got married very young, had a bunch of kids and he was talking about how he compares their two lives, and it kind of resonated with me a bit. A couple other things that resonated with me, he talks a bit about what he calls Chesterton’s fence.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Ari:

Haven’t really researched it too much, but he has a great quote, it goes something like “Tradition is the solution to problems whose nature we’ve forgotten.” I believe that’s the quote, something along those lines. And that one definitely made me think a lot, because it is very true that these days people try and sort of tear down fences just because the logic is, if there’s a fence, well that’s restricting you and you don’t want to be restricted at all, right? You want to be able to do whatever you want, so you don’t want a fence in the way you want to be able to just have the freedom to do whatever you want. But it’s true that a lot of those fences are there for reasons. And the most obvious way to see how those fences oftentimes have very positive effects is to look at comparisons between what I would call the Orthodox Jewish world and the generic secular world. So take modern life in America and a lot of the problems it has and compare it to the Orthodox world and some of the problems it has, and one example I see in my personal life is looking at people who have raised their kids Orthodox, raised their kids a certain way, versus people who have raised maybe a slightly less Orthodox way, maybe they do Conservative, Reform, maybe not religious at all.

And you kind of look at down the line. So once an example close to me is my grandmother versus her sister. So my grandmother chose to raise her kids religious. Her sister chose not to raise her kids religious for various reasons I’m not going to get into, but you kind of look at it now and my grandmother has a big Orthodox family. Of course they have a bunch of kids, so she only had two kids, but down the line, the Orthodox families tend to have big families that are generally, they get along pretty well. Whereas my grandmother’s sister, she had just one kid and that kid had another two kids. And it’s just a small family. They’re kind of not a big, what I’d call a big happy family, which I think comes with a whole bunch of benefits of its own, having a big happy family.

But that’s just one example. I think if you examine a lot of areas of Orthodox life, it kind of gives you a good mold to kind of shape your life into a path that is very beneficial. Antonio talks about this a bit too actually, he talks about how you have stuff like let’s say the death of a loved one, so there’s Orthodox way of handling that. So you’d sit shiva and you say Kaddish, et cetera, et cetera. Whereas in the non-Jewish world if someone dies there’s really no set structure. I mean, there’s a funeral, but beyond that, it’s kind of… There’s no mold to fit into, it’s kind of just do whatever you want.

David Bashevkin:

It resonates so much with me because it’s so similar to my own family. My father, he has one brother who we’re extraordinarily close with, but… my father raised a religious family, kind of was almost a black sheep who went off, and my uncle did not. And the way the family unfolds and looks now is quite different. As much as I love my uncle, and he knows I love him, and he listens to this, it really does look quite different. I’m curious if you could tell me a little bit because I identify with it a lot, but I’m curious what it means to you. Why is optionality not the ideal, meaning what’s the pain of optionality? Modernity, if it offers anything, it is the ability to choose whatever you want. Why does that create problems and not just solve them in your mind?

Ari:

I think for one, you really need to, a lot of things in life, you have to really commit to them for them to work. You can’t kind of, excuse my language, you can’t half-ass them, because then it doesn’t really… You’re not getting the full experience. You’re not really… If you don’t commit to it, you’re doing it wrong. And of course you’re going to get bad results if you don’t do it correctly. I mean, an example kind of similar to what we were just talking about that comes to mind for me is dating in Jewish world, or I guess in the Orthodox world versus non-religious or secular world. In the Orthodox world, you date with very serious intention. It’s not just dating to kind of date.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Ari:

In the secular world, there’s a lot of optionality in dating, which I think is part of the reason there’s so many problems with modern-day dating in the secular world is because of all the optionality.

People go on an app and they see a million different people and wow, so many choices, how can I just pick one? Obviously back in the day, a couple hundred years ago, you were kind of stuck with whatever was around you, you couldn’t really hop on and out.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Ari:

And the Orthodox mold kind of maintains that in a sense, because it forces you to pick one person and now you’re committed to one person and that’s your person. It’s not… You don’t have that optionality. And I mean, look at all the unhappiness that happens with secular dating these days, it’s very obvious that it’s a terrible system. I mean, it does maintain, in a literal sense, maintains your freedom to do whatever you want, but at what cost? I mean the cost is now you’re unhappy, or you don’t have someone to be with long term, or whatever, the many issues. And it’s not like the Orthodox system is perfect, I mean, it has issues on its own.

David Bashevkin:

No. Yes.

Ari:

I mean, comparing something like the shidduch crisis to the disaster that secular dating is, it’s just not even comparable on scale.

David Bashevkin:

I’m curious for you, if you’ll allow me to ask, because I really do… We don’t know each other. I only got connected to you through an email. We’ll call you Ari for the sake of this conversation and leave it at that. But one thing that I’m curious about is you said you basically were an atheist since 10th grade, and I assume your observance level slowly tapered off, maybe it wasn’t all in one fell swoop, but it tapered off since 10th grade. What have you learned since moving away from the Orthodox community? Were you kind of disillusioned? Were you surprised by your own interior experience? Did you think that you would be happier, would provide you more of a path? Meaning, were you surprised by the experience of secular life or this is kind of what you had signed up for?

Ari:

I’d say in the short term, it was what I signed up for, in the long term it was not. I think looking out from inside the kind of Orthodox community and Orthodox lifestyle, it all looks, I guess the grass is always greener on the other side, but it all looks very fun and there’s so many things you can do. And so many things you can try that you can’t really do within the Orthodox system so much. I think long term, some of the problems with the secular system start to show through.

David Bashevkin:

I can’t thank you enough for your willingness to speak. It’s not every day that you get an email from some random podcast host asking to respond to a private email. And it really was very gracious of you. I’m curious if you could go back and almost speak to that younger self, I just want to be clear I’m not even assuming that you are now Orthodox, I think you made it clear that’s not the case. That you’ve like done this miraculous, the 180 and reinvested your whole life. I think that reorientation of thought is powerful in of itself. If you were to go back and speak to that younger self, aside from this essay, what do you think you could do to help them feel more at peace in their religious life, in their religious community?

Ari:

Well, I think for myself, what would’ve impacted me more is less so an argument for why the religion is true and the things that it says are true and more so the benefits of actually having the religion. I think the problem I had back then was I didn’t really have a good understanding of the secular world. It looked so glamorous with all the different things I could do that I couldn’t do back then, and all the optionality, I guess you’d say, but I would try and I mean, hopefully explain to my past self that those things you can do and the optionality you have are nice in the short term, but in the long term they don’t really pan out. There isn’t really any substance behind them. And in the Orthodox world, there’s a big support network. It’s a big community. You’re not taking on life alone. You have a mold to live life in, and it’s just a much better life overall.

David Bashevkin:

I find that very moving and your reorientation, very moving. My final question, if you’re comfortable sharing, is aside from this essay, which obviously moved you, has there been any other writing essays, articles, or books that have helped you reorient, and they don’t have to be overtly religious, but have helped you reorient your relationship to religious thought, religious community itself?

Ari:

There was one by this writer, Christine Emba, her book is called “Rethinking Sex,” and she talks about modern-day dating and attitudes towards sex and why she thinks they’re detrimental to us, and sort of what a better way of treating it would be. And it does align sort of similarly to the Orthodox position where she talks about optionality, and she talks about how sort of attitudes have changed, and why the older traditional system has a lot of benefits that the new secular system does not have. And I found it changed my views on sex a bit also, and my views on dating and marriage.

David Bashevkin:

Again, that’s Christine Emba and the book is called?

Ari:

“Rethinking Sex.”

David Bashevkin:

“Rethinking Sex.” And as strange as it may seem, maybe to some of our listeners, I happen to think that the lens about thinking about commitment in relationships and how we think about fostering intimacy has always been one of the primary lenses, I think, about my own religious life. I struggled with optionality myself and the ability to nurture commitment and focus in my life. There were times when I found commitment quite suffocating and optionality quite liberating, but I’ve learned to really appreciate everything that you’ve been saying, which is the joy and real intimacy of relationships that come with commitment and with long-term focus, rather than just the endless exploration of the options you have. Ari, I can’t thank you enough. Is there anything else you would want to add about your story to our listeners? Again, I want to make it clear cause I don’t want to misrepresent you or feel like I’m trotting you out like some ba’al teshuvah show pony, so I want to make that really clear that’s not what we’re doing at all. I was just really generally moved from that email, and let me know, is there anything else you would want to add to your story, to your journey?

Ari:

I think we summed up pretty well. It’s true, I’m not really, I wouldn’t consider myself even really a ba’al teshuvah because I feel like a ba’al teshuvah, I mean, some name you have to have teshuvah and I don’t really think I have teshuvah, in a literal sense. I think I see value in the lifestyle more so than that I regret the things I’ve done. I don’t really regret any of the things I’ve done, especially because they’ve built me into the person I am. But if I could go back and change some things I would, but yeah, I think you represented me very fairly and it’s about it.

David Bashevkin:

This notion of optionality and what the outside world, so to speak, opens and what we could gain by leaving our religious life often obscures the real question, which is what do we lose? What do we lose from having those unchosen obligations that ultimately, as discussed in this essay, really shape and develop our sense of self and bring that long-term joy though it may be amortized over the very course of our lives. And it’s a remarkable essay that I’ve read large snippets from it but I would encourage all of our listeners to take the time out. His website is called thepullrequest.com, and the essays, once again, it’s two parts. One is called “Why Judaism: On abandoning secular modernity.” And the second part is called “Why Judaism Part Sheni: On the question of God in modernity.” Not everything that he says, Antonio is not a rabbi, not everything he says you’re going to agree with. But as an essay that couches contemporary commitment into the language of what it means to be modern in today’s day and age, I can’t think of that many people who have done it better. And that’s why it was so exciting to speak to Antonio and of course, ask him the questions that we ask all of our guests.

I always end my conversations with more rapid-fire questions, I’m wondering if you could indulge me.

Antonio García Martínez:

Sure.

David Bashevkin:

The first one should be fairly easy. I’m wondering for book recommendations, what books would you recommend for somebody who wants to think about the way they are thinking, kind of the topic that we are talking about today? I think at the heart of what you’re talking about is about this optionality and wedding yourself to tradition, wedding yourself to commitment. What are the books that pave the road to getting where you are? They don’t need to be Jewish books.

Antonio García Martínez:

One of the books, I mean, if you’re academically or philosophically inclined, there’s a British philosopher by the name of John Gray, who wrote a book called “The Seven Types of Atheism.” He’s pretty well known in the UK, he writes for UnHerd. For some reason, he hasn’t quite made the hop to the U.S., but his book, “The Seven Types of Atheism” classifies various flavors of anti-religion of various forms. And even though he’s an atheist himself, to be clear, he’s not from any particular religious domination, he just from a very dry academic point of view, he just takes apart their reasoning, including the new atheists.

David Bashevkin:

Dawkins, Hitchens, Sam Harris.

Antonio García Martínez:

Right. So it’s good to see a very smart erudite… man kind of tear atheism and it’s many flaws apart. Although it’s funny at the end of the book, he comes to his own conclusion, which just like, and I asked this question to Neil Ferguson, who I also interviewed and he was raised, I think, Scottish Presbyterian. And he’s like, I agree with you Antonio, we need religions, but I just can’t bring myself to actually believe in Jesus.

David Bashevkin:

It’s a bridge too far.

Antonio García Martínez:

It’s a bridge too far. So, yeah. Maybe yeah, John Gray’s book would be a good one.

David Bashevkin:

“The Seven Types of Atheism,” I love that. It’s a great recommendation, what I was looking for. My next question, I always ask if somebody gave you an unlimited, a great deal of money and allowed you to take a sabbatical for as long as you need to go back to school and actually get that PhD, what do you think the subject’s title of that PhD would be?

Antonio García Martínez:

Interesting. Yeah, I wouldn’t go back to the sciences at this point.

David Bashevkin:

What were you in the middle of writing? What was that first PhD going to be on?

Antonio García Martínez:

Experimental physics. It was low temperature condensed matters. It’s not a sexy as it sounds. It was wiring together and building complicated devices that never worked and hoping to get a measurement.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. But that that’s exactly where I was going. That is the sexiest sounding PhD title I’ve ever heard. But what would you go back now to study?

Antonio García Martínez:

It’s going to sound ridiculous and almost like I’m shilling, but I probably go to Israel and learn Hebrew and be steeped in Israel, spending a year in Israel, everywhere from the West Bank to Israel proper and learning Hebrew, that’s what I would do.

David Bashevkin:

Is there an area of Jewish Torah study that resonates most with you, that you are able to certain writers, Jewish writers, you mentioned Herman Wouk?

Antonio García Martínez:

This reveals maybe my conservative bias, Rabbi Heschel and the Sabbath.

David Bashevkin:

Heschel’s on my shelf too, my friend.

Antonio García Martínez:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

He transcends any… He’s bigger than any and he kind of rejected kind of the denominationalism that he was pigeonholed into. And I also reject those who pigeonholed him into a particular denomination. I think he was much bigger than that, and we’ve interviewed his daughter on 18Forty when we did a series on Shabbos, he’s really special. My last question is I’m always interested in people’s sleep schedules, because mine is so terrible.

Antonio García Martínez:

Oh God.

David Bashevkin:

What time do you go to sleep at night, and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Antonio García Martínez:

Man, mine is terrible, that’s why I feel like I’m blubbering in this interview. And once you get to a certain age, I literally just posted a joke meme that I used to work a crazy amount of time, go out drinking.