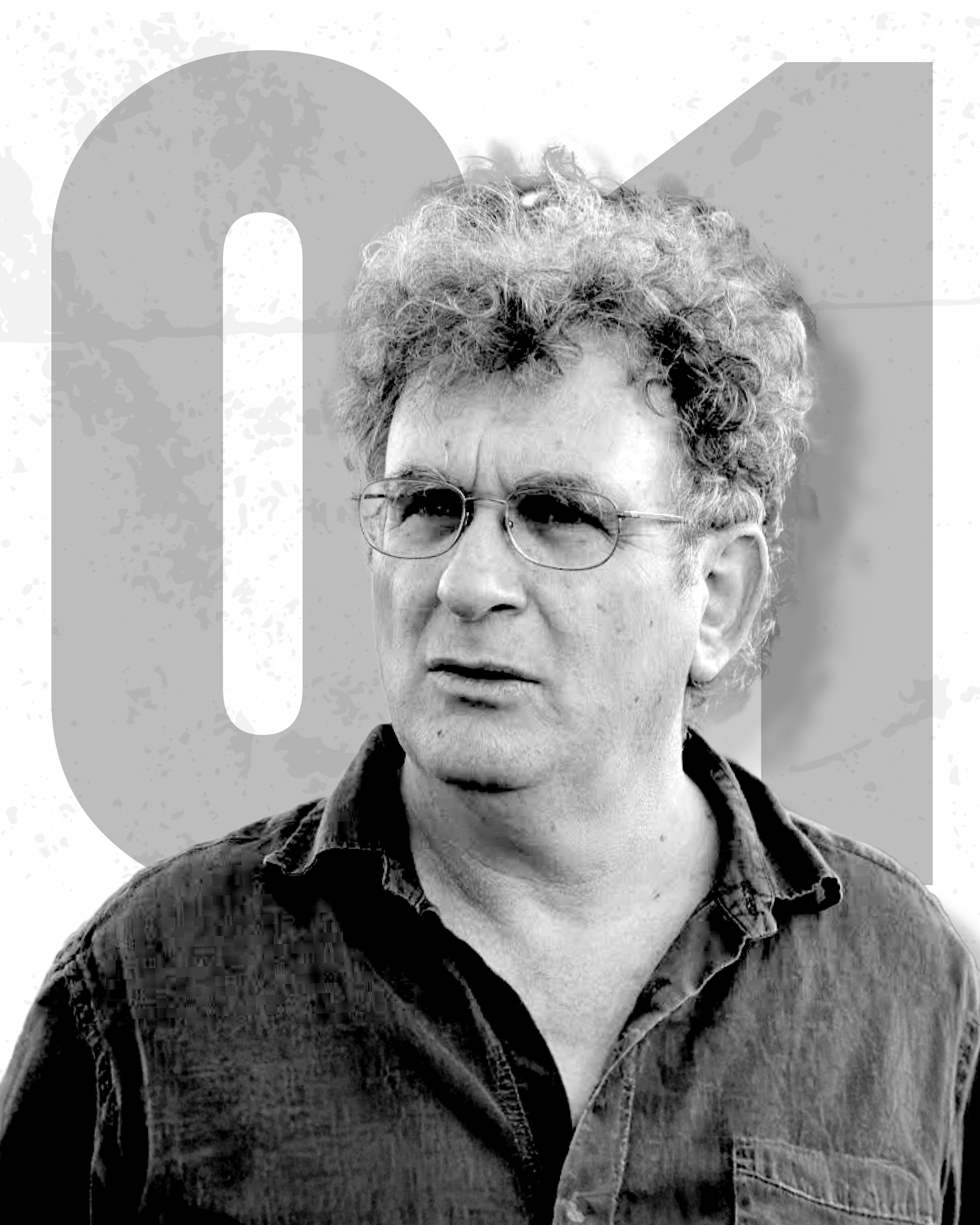

Michael Oren: ‘We are living in biblical times’

Israel is a heroic country, Michael Oren believes—but he concedes that it is a flawed heroic country.

Summary

Israel is a heroic country, Michael Oren believes—but he concedes that it is a flawed heroic country.

Michael Oren—our 40th Israeli thinker—served as Israeli ambassador to the U.S. from 2009-2013 under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, while former U.S. President Barack Obama was in office. A diplomat, writer, historian, veteran, and political thinker, Michael worked extensively in all fields of defending the Jewish state.

He is the bestselling and award-winning author of several fiction and non-fiction books, including Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide and Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Michael is working on a book on October 7.

Now, this unapologetic Israel advocate joins us to answer 18 questions on the war in Gaza, the IDF’s morality, and satanic accusations against Jews.

This interview was recorded on July 10.

Transcripts are lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

Michael Oren: Yes, there have been mistakes in this war, there have been mistakes in every war. We’re a heroic country, but a flawed heroic country. We’re a country of human beings. And there actually is no country on earth like this country.

On the flip side of that, and I used this with very hostile interviews, this was with the Irish radio the other day, was to say, they’re saying, “Well, you are committing genocide, you are starving Palestinians.\” And besides taking apart the genocide argument and the starvation argument, you say, “Why are you accusing Israel of this? You’re accusing Israel of this because you must believe at some level that the Jewish people are inherently evil, that we wake up in the morning and want nothing better than to kill Palestinian children, nothing better than to starve Palestinian civilians.” And when you say things like this, to me, I hear the echoes of the 11th, 12th, and 13th century, and that nothing has changed. In Ireland, nothing’s changed in Europe. And by the way, that’s not a propaganda line, that’s absolutely true. Hello, I’m Michael Oren, formerly Israel’s ambassador to the United States, former member of Knesset and deputy minister for diplomacy.

And this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers from 18Forty.

Sruli Fruchter: From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter. 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas war, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else.

So if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today. This is the final interview for 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers. If you have been keeping track, today we are interviewing and hearing from the 40th Israeli thinker. Thank you all so much for such an amazing season.

When Dovid Bashevkin and I first were discussing about what our goals were for this podcast, it was really created in an effort to think about how 18Forty could meet the moment for what was happening in America, in Israel, to the Jewish people, and think how we could bring an 18Forty touch to the seismic changes in the Middle East, North America, and beyond. The idea behind 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers was that we are not a political organization, we are not a breaking news organization, nor do we ever want to be. But one of the big things that lies at the core of everything 18Forty does is expanding our horizons, approaching new ideas, difficult questions, and fresh perspectives with that authentic, traditional brand of Jewish curiosity. And so we thought, while we aren’t going to be speaking about or trying to explore on our own the political and sociological landscape in Israel, what if we could expand our horizons by platforming the conversations and the voices in Israel today.

And so when we thought of 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, our goal was to try and bring the most legitimate, influential, and substantive perspectives from all types of Israelis, whether they are right-wing, left-wing, centrist, political thinkers, religious thinkers, journalists, activists, not even Jewish. And I think that for myself, like anyone, I have my own opinions and I have my own perspectives. But coming into this series, trying to be objective in the questioning and really trying to allow all of our guests to explain themselves, explain their ideas, how far their ideas goes, has been such a privilege. And from the feedback that we get from our listening community, those who love some episodes and hate others, those who learn something new and those who think that someone gets something wrong, I really do think that we accomplished that.

And so on that note, today’s guest is an extraordinary voice in Israeli society. He is someone who we knew needed to top off the series. He is a historian, a writer, a political thinker, someone who grew up in America and moved to Israel when he was young, served in the IDF, and made his way into the Israeli government and the Knesset. The Forward named him as one of the five most influential Jews in America, and The Jerusalem Post named him as one of the ten most influential Jews worldwide.

Today’s interview, our final for this series, 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, is Michael Oren. Michael Oren was the ambassador of Israel to the United States from 2009 through 2013 under Netanyahu and during the tenure of the American president, Barack Obama. Michael was elected to the Knesset as part of the Kulanu party in 2015, serving on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, and the following year he was appointed as deputy minister.

Michael Oren: Minister for Public Diplomacy in the Prime Minister’s office.

Today, aside from being a prolific author and advocate, he has written a handful of award-winning non-fiction and even fiction books and is currently writing a new book on October 7th. Michael heads the Israel Advocacy Group, which, quote, relentlessly advocates for Israel and the Jewish people around the world by spearheading and leading behind the scenes diplomatic efforts to strengthen Israel’s relations with the United States and the world. I have so much appreciation for Michael’s perspectives and nuance and was really surprised in some areas of the things he was willing to say, of the critiques he was willing to level, and of the candid nature with which he approached and spoke to me during this interview. So I hope that you enjoy this interview and before we get into it, I want to still hear from you.

Please, tell me what has been your favorite episode, your least favorite episode, what have been the highlights, what have been the things that surprised you. We always view our podcast channels as so much more than just a space for people to listen to new ideas, but as really an extension of the community that we build across all of our platforms, events, and programs. If you have ideas for what you would like to see from this podcast or from 18Forty next, again, we want to hear from you. And on a last and final note, 18Forty has just launched a completely revamped, redesigned, and redone website where you can now see in a beautiful, aesthetic format, all of our articles, essays, podcasts, videos, book recommendations and can just get lost in the site.

Really, it is not something to be missed. So enough for me, and without further ado, here is 18 questions with Michael Oren.So, we’ll begin where we always do. As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

Sruli Fruchter: Best to quote an imminent source, my cab driver. My cab driver says we’re not living during historic times, we’re living during biblical times.

And I think that’s very, very accurate. We’re dealing with a period in Jewish history that will be remembered by the Jewish people for hundreds and perhaps thousands of years.

Michael Oren: How does that feel?

Sruli Fruchter: It feels, I feel very privileged. But I also feel the weight.

I feel the weight of that moment. A moment, say a Maccabean moment, a moment of coming into the land of Israel. I don’t want to go to call it a Sinai moment, but it’s certainly a momentous moment for a momentous period for Jews.

Michael Oren: How does it compare to other moments in Israeli history in which have also felt momentous? Like of course, this is not your first rodeo, so to speak.

Sruli Fruchter: Yes, okay. In the Israeli textbook. So, certainly the declaration of Israel’s independence on May 14th, 1948, the Six Day War, the visit of Anwar Sadat to Israel in November 1977. I was present at the signing of the Jordan Israel Peace Treaty in 1994, and the forging of the Abraham Accords in 2020.

These are all momentous events. There’s also tragic events. Of course, the opening day of the Yom Kippur War, October 6th, 1973, the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995, the years of the second intifada, and the various wars we’ve had, certainly and the terrorist attacks, and above all, October 7th, 2023.

Michael Oren: Does anything feel different to you about this?

Sruli Fruchter: I feel that I have a deep sense of hope here.

It doesn’t, it’s not Pollyanish. I have deep and abiding concerns. Most of them relate to internal issues in Israel, not our external relations. But there too, I see the tremendous reduction in support for Israel around the world, particularly in the Western world, particularly among Americans, particularly among American Jews, particularly among young American Jews.

But I see that this country is by far the strongest society on the planet. I, I draw great strength from the fact that we have a loyal elite, which is not to be taken for granted. Much of the West and the United States does not have that type of loyal elite that’s willing to go out and fight for the country, certainly not to die for the country. And we have a generation of young people who have now spent hundreds of days in combat.

And they have fought side by side with left-wingers and right-wingers and religious and secular and Ashkenazim and and Mizrachim. And they’re deeply patriotic and committing to make this place a much better and more secure country. And they will be leading this country in the year to come. And I think that’s a source of great, great optimism for me.

They’re the greatest generation we’ve had since 1948.

Michael Oren: What do you think has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in the war against Hamas?

Sruli Fruchter: Well, I think my background is as a military historian, and I’ve taught military history, and I will tell you that without parallel, this is the greatest single military victory in modern history. I think it, it actually exceeds the Six-Day War. It even exceeds the 1973 war, which, beside the fact that it was, it began with a horrendous surprise attack, was one of the great military.

Michael Oren: military triumphs of of of the of the modern age because it it ended with Israeli artillery within range of Damascus and Cairo. But this war is actually more impressive. It’s actually it’s beyond the realm of impressive. Just take the Gaza front.

You know, when the United States Army fought in Iraq, the two most grueling battles there were Fallujah and Mosul. And in Fallujah and Mosul, the US Army, no small military force, encountered a rebel force of about 5,000 men in cities that were largely abandoned with no tunnels. In Gaza alone, the IDF encountered a Hamas force of 30,000 terrorists in an area that was densely built up of about two million people with very little area to evacuate and something in the order of 500 kilometers of tunnels, which no army in every in history’s ever encountered. And it did this and it won to the degree it can win militarily against the enemy because it was holding hostages and hiding behind a civilian population.

So again, if you’re if you’re just studying military history at West Point, you want to look at this battle because nothing’s ever been like it. Now that’s just Gaza. It’s not Lebanon.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Michael Oren: where, according to all the estimates, including of US intelligence, Israel was incapable of beating Hezbollah. Hezbollah was one of the one of the most powerful military groups, not just in the Middle East, but anywhere in the world. And Israel beat Hezbollah. And then Iran.

And then most recently, Iran. And that was, again, that’s going to be studied for 50 to 100 years from now in any military group around. So that militarily, there’s no question. The big question is there there is a question is whether Israel can then translate those military victories into strategic triumphs.

Sruli Fruchter: Strategic meaning long-lasting political resolution?

Michael Oren: Well, for example, with all of the success of these military operations, there’s still a Hamas force in Gaza. There’s still Hezbollah in Lebanon and there’s certainly an Iran which is still under the regime of the Ayatollahs, is still quite quite formidably armed.

Sruli Fruchter: And that you would say is Israel’s greatest mistake in the war?

Michael Oren: So right, no, it’s not not yet.

Sruli Fruchter: Uh-huh.

Michael Oren: I haven’t come across the success. I’m saying I’m still on the successes. But there’s still the questions.

Sruli Fruchter: Okay, great, perfect.

Michael Oren: And so, Hamas no longer threatens us strategically. Hezbollah no longer threatens us strategically. So those are military successes that have been transformed into strategic successes. It’s yet to be seen whether we can make that same type of translation in Iran.

Because the Ayatollahs are going to come back and they’re starting already, even as we’re talking. They’re sending terrorist groups across our borders. And the question is will Israel continue to deter Iran and will the United States both give us the permission, give us the green light to do that? And will the United States perhaps join us again in deterring Iran? And that is the only way to translate that military victory into a strategic success.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

And so what would you say has been Israel’s greatest mistake in this war?

Michael Oren: Well, there are in any war, there are great mistakes. I mean, you can say that in Gaza, Israel, the IDF should have invaded Rafah first instead of last.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Michael Oren: I was a huge proponent back in early October that Israel should strike Hezbollah first.

I was of that school. And by the way, I’m still of that school. And though the Prime Minister disagreed. And there were there were compelling reasons why Israel should have attacked Hezbollah first.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm.

Michael Oren: But, you know, you make decisions in warfare, and some of them are good and some of them are less good. You don’t know actually what the outcome is going to be. I think that one of the failings of the war is that Israel almost entirely abandoned the public diplomacy diplomatic front, which is what I’m involved in.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah.

Michael Oren: And found ourselves, I found myself and an NGO that I created, the Israel Advocacy group, founded on October 8th around the kitchen table downstairs with a bunch of volunteers, basically to fill a vacuum because the state was not doing nearly enough to defend itself, and we’re still doing it. Now, it doesn’t mean that that’s a winnable battle because we’re up against a social media that’s, you know, social media, certainly a mainstream media which is very, very hostile to us with unlimited resources, but we still have to fight it. And I view my job, every time I go on, you know, CNN or BBC, my job is to create time and space for the IDF to do what it has to do to defend us.

But not nearly enough was done, and that was a huge failing, and we we will we’re still be paying the price for that.

Sruli Fruchter: I see you’re wearing the yellow hostage pin and I think today it’s 630 or 640 something days since the hostages have still been in Gaza, those who are remaining, those who are alive and dead. Has that been handled properly?

Michael Oren: Well, I’m of the school that says that there’s actually no way of reconciling the two. From the very first day we started…

Sruli Fruchter: Reconciling the two goals of the war.

Michael Oren: The first day of the war, there was two goals. One was to destroy Hamas and the other was to rescue all the hostages. And I believe from day one that these were mutually incompatible. And so you you did your best to try to put pressure on Hamas to release hostages, but we found out to our great, great distress.

that the more pressure you put on Hamas, Hamas doesn’t necessarily release hostages, it executes hostages. So it creates a dilemma which no country, certainly no army, has ever faced in modern history. And having worked with Prime Ministers and having worked with this Prime Minister, and that doesn’t mean by any stretch I agree with everything he’s done, I know that he sees things that many people don’t. So the majority of Israelis right now think that we should accept pretty much any deal that Hamas wants, let Hamas win, have the IDF withdraw, have a declare the end of hostilities, as long as we can get all the hostages back.

And that’s assuming the Hamas actually will give us all the hostages back. I sincerely doubt that. Hamas will always keep a few. And but the Prime Minister is going to look at this and say, okay, you get the hostages back, which is very important for maintaining our our national coherence and resilience and preparing for the next war.

But on the other hand, who’s going to move back to the south? Hamas just fired seven rockets at the at the southern part of the country this this week. What happens with Judea and Samaria? Does it go up in flames? What happens with our international standing and can we make peace with Arab countries who are depending on Israel to stand up to jihadist terror? That’s why they make peace with us. And so the ramifications of accepting that deal is not just dealing with a ceasefire in Gaza. They’re regional and indeed international.

So I don’t propose to say that this has been handled wrong or rightly. And I don’t agree with everyone who thinks that everything that Netanyahu does is is impelled by politics. Yes, there’s politics. He’s a politician.

But I also know that the decision whether to give into Hamas’s demands is not so simple. And it’s not even simple to whether even even Hamas is going to accept it.

Sruli Fruchter: I want to shift to talk a little bit more broadly about Israeli society. What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for? I’m not asking who you vote for, but I’m curious what considerations you make when you’re casting your vote.

Michael Oren: Okay, two. Two. I would belong to a party that doesn’t exist anymore. And that party would be Yigal Allon’s party of Ahdut HaAvoda.

And it’s interesting that when I ran for Knesset and was in Knesset, I ran with a party that that whose platform was the closest to Ahdut HaAvoda, and that was Kulanu. And what is Ahdut HaAvoda? Ahdut HaAvoda was right of center on strategic and defense issues and left of center on social issues. Right of center on strategic and defense issues, because that’s the only way we can survive in this neighborhood. Left on social issues because I believe that the Jewish state has to provide extensive safety nets for the weaker parts of the society.

We cannot be like, say a full, free market capitalist society where we step over homeless people in the streets. We can’t do that. It’s not a Jewish state. And to this day, and it’s not widely known that Israel has the widest social gap of any country in the world after the United States, Chile and Mexico.

We have a million children beneath the the poverty line, the poverty line in this country. And yes, we have a per capita GDP which is neck and neck with Germany. We’ve passed Japan and Italy, Austria. But that that wealth, that national wealth is really confined to the high-tech sector.

It’s about 13, 14% of the population. The rest of the population is pretty poor. And so I I feel very much a responsibility for that part of the population. So it’s it’s Ahdut HaAvoda.

I also want a party that cares about our foreign relations. And this country can be very insular, can be very parochial at times and not be very much aware of what’s going on in the world.

Sruli Fruchter: Which is more important for Israel? Judaism or democracy?

Michael Oren: See, I don’t think a contradiction between the two. I think a Jewish state has to be democratic.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you see why people see a tension between them? Like take for example judicial reform.

Michael Oren: Right.

Sruli Fruchter: Which many saw as those two sides of Israeli’s identity coming coming head to head essentially, where there was that tension between which part of Israel’s character would dominate.

Michael Oren: And I and I was long of the opinion that there needed to be correction.

So I was in Knesset, I worked on judicial reform. I I wrote a book called Israel 2048, which has a whole section written well before, actually written before the controversy of judicial reform where I advocated for judicial reform. And it clearly needed to be corrected and that the the balance between Jewish state and democratic state had had sort of gone awry and had to be redressed.

Sruli Fruchter: How did you see it going awry?

Michael Oren: Well, for example, well, some of it was just very technical, but beginning in the early 90s, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Aharon Barak had passed a piece of legislation that clearly gave preference to the democratic nature of the Jewish state.

And and there were other issues there too, the activism of the court, the court that arrogated responsibility over virtually every aspect of Israeli life. Everything was was adjudicable. That’s was the line. that had to be changed.

And also the way Supreme Court justices had to be changed, the way they were elected had to be changed, because basically the Israeli electorate had almost no say in who became a Supreme Court judge. And that was very much at variance with the American system and almost all systems in the world with the exception of India and Thailand. I mean really. We were in a very small category.

So it had to be redressed. Did it have to be redressed in the way the government did it? No. What the government did was to take away judicial review. It basically neutered the Supreme Court.

And I saw that judicial review, that is the, the idea that the Supreme Court has the last word as a pillar of democracy. And it took it away. So I think it just went too far. And and the opponents of it also went too far by saying there could be no judicial reform whatsoever.

But I was also aware of the social, economic, ethnic, and religious components of this debate, which were widely, widely overlooked. So where were these protesters breaking out? They were breaking out in the in the affluent areas of Tel Aviv, Herzliya. There weren’t a lot of protests against judicial reform in in, you know, Kiryat Malachi and Kiryat Gat and in Kiryat Shmona, right? That even the units that were saying they weren’t going to go report for reserve duty. What were those units? They were pilots and commando units.

Not weren’t a lot of, weren’t a lot of Golani troops saying they weren’t going to report for reserve duty. And in my neighborhood, especially, this in Jaffa, and the and the community I belong to, which is largely Mizrachi, Eastern, religious, and working class, they saw the struggle over social, social reform, of judicial reform, not as a, you know, a battle over democracy, but just the opposite. It was a battle against democracy because they thought that the people protesting against the government were people who didn’t would not reconcile with their loss at the polls. And they were rallying around the last bastion of affluent Ashkenazi secular elite, which was the Supreme Court.

So they, they viewed it a completely different way. I mean, I had written an article for for the Times of Israel where I talked about a tale of two Tel Avivs. So this is one Tel Aviv, but then I also am a rower. I mean, I belong to a rowing club on the Yarkon River.

The members of that rowing club are all affluent, secular, left-wing Israelis. And so a difference, a difference of a couple of kilometers and you had completely different views of what this debate was about. So, clearly, there’s always going to be a certain tension between the Jewish state and the democratic state, but that tension does not have to be overwhelming, and it can be bridged. You know, there are 194 states in the world.

The vast majority of them are nation states. And many of them have national religions. Denmark has a national religion. Great Britain has a national religion.

Sruli Fruchter: But not all countries have to deal with that the same way. Meaning, the way that Judaism takes form in Israel’s national conversation in terms of the laws, in terms of certain preferences or treatments that Jews get over non-Jews. Isn’t isn’t that something that’s different between nation states?

Michael Oren: They’re all going to be different. Look, so there’s going to be that tension right now going in Europe, between the nation state and, and the population, for example.

What’s going on with the immigration issue in Europe? And you’re seeing a huge backlash. So, there too, there’s tension. There’s always going to be tension. Even in the United States, which is a multinational state put together, there’s tension about what it means to be an American right now.

Look what President Trump trying to do with all the, you know, supposedly with the immigration issue and deporting all these people, saying they’re not American. I think Israel is unique. Israel is unique for many, many ways. But being tension-free is not one of them.

Israel doesn’t fit into any, actually, actually total category. The closest parallel to Israel is Japan. Why? Because Japan is an island, we’re kind of an island. We are a nation state.

We have a national religion, we have a national history, we have a national language. Japan. There’s one huge difference between Japan and Israel, which makes Israel completely, completely unique, unique among all nation states. If you’re a, you know, a Catholic kid running and growing up in Long Island and you wake up one morning, you decide to be Jewish, you go through a certain process, and you acquire not just Jewish identity, but you acquire 4,000 years of Jewish history, and you are part of the Jewish nation.

Whereas if you’re a Catholic kid growing up in Long Island, you can’t wake up in the morning and decide to be Japanese. That’s a huge difference. And I don’t know any other country in the world like it. Which by the way, makes it very difficult to to defend Israel sometimes because because we are so unique.

Sruli Fruchter: Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

Michael Oren: It should treat them the same on a legal basis, but not on a national basis. The Arabs in this country or the non-Jews in this country, not all of them are Arabs, have full civic and political rights, but they don’t have national rights. This is not their nation-state. And I believe that they don’t have the right of return.

Now, many nation-states, you’d be surprised how many nation-states have a right to return. We’re not by far not the only ones.

Sruli Fruchter: Now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

Michael Oren: Zionism today has a greater purpose maybe today than at any time in history because we are the only country in the world, you know, whose national, whose right to existence is daily being questioned. And and with increasing frequency being questioned.

And Zionism for me has always been synonymous with basically one word which is responsibility. It means taking responsibility for ourselves as Jews in this country, which is the only place where we can really take responsibility for ourselves as Jews. Okay, you can be a Jew living in New Jersey, you can take responsibility for all sorts of things, but you don’t take it as as a Jew. So here as Jews, we’re responsible for our, you know, our our electricity, our sewer system, our defense, our foreign policy.

And that’s a very weighty, weighty responsibility. And it means dealing with, you know, mistakes, sometimes very painful mistakes. But that’s our responsibility. That’s what Zionism means for me today.

Sruli Fruchter: So, is opposing Zionism inherently anti-Semitic?

Michael Oren: It has become.

Sruli Fruchter: How so?

Michael Oren: How so? Well, 194 nation-states in the in the world, right? Only one of them doesn’t have a right to exist, just just happens to be the Jewish state. There are tens of thousands of peoples in the world but only one people does not have the right to self-determination. That’s the Jewish people.

And under the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism, singling Israel out, singling is by definition anti-Semitic. It is. Now, the other day was a a decision made by the British government to sanction two Israeli ministers. And, and I went on the BBC and I said, listen, I don’t agree with what these ministers do.

I don’t defend them. A lot of what they do is repugnant to me. But that this decision is anti-democratic, you know, because God knows these people were democratically elected whether you like it or not. You start sanctioning everybody who’s democratically elected, and and you don’t agree with them, you’re not going to have much democracy in the world anymore.

I said it was anti-British because we’re fighting the same enemies. They’re trying to take you down, you know. But I also said the decision was anti-Semitic, which really got them. Why was the British government’s decision to sanction Mr. Ben-Gvir and Smotrich, why was it anti-Semitic? Because the British government is not sanctioning China that puts a million Muslims in concentration camps.

It’s not sanctioning Qatar, Turkey, which support terror. It’s not sanctioning anybody else. It’s only sanctioning the one Jewish state. That by definition is anti-Semitism.

Sruli Fruchter: You said that it that it’s become so, that was there ever a point for you when you didn’t think that opposing Zionism was anti-Semitic?

Michael Oren: I grew up in a different generation where they were Jewish organizations, including Jewish organizations that are very Zionist today, that weren’t. That weren’t. And you could have, I knew many people who, you know, growing up and also people I studied with who were not in favor of a Jewish state, but they weren’t anti-Semitic. My advisor, in college, was fabulously anti-Zionist.

But I didn’t detect the slightest whiff of anti-Semitism about him. But things have changed.

Sruli Fruchter: Is the IDF the world’s most moral army?

Michael Oren: I think if I define it’s a low bar. True, but it’s a low bar.

Why? Because how many armies have actually fought in recent years? The United States fighting in Iraq and, and Afghanistan, the Russian army fighting in Ukraine, and really, that’s the low bar. When our detractors throw out a number that’s taken from Hamas. Hamas, the the the so-called Gaza Health Authorities, which are a series of oxymorons, but actually nobody knows who they are. Nobody can actually name them.

But they’ll say that 56 or 57,000 Palestinians have been killed in this war. And the IDF has killed probably more than 22,000 terrorists. There have been several hundred if not several thousand Palestinians killed by Palestinian rockets that fall short. 12% of their rockets fall short.

And out of a population of over 2 million over the course of 20 months, about 8,000 people die of natural causes. So if you deduct all that from the 56, 57,000, you’re going to get roughly a one-to-one civilian to combatant fatality rate. When the United States fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, at the very least, it was nine civilians to every combatant. And sometimes it went up to 26 civilians to one combatant.

Does that make the Israeli army more moral? It does. It does. That if any other country had sustained the type of attack that Israel attacked was sustained on October 7th, which, you know, there were 1200 Israelis and our guests killed, the equivalent of 44,000 Americans. If 44,000 Americans were killed over the course of four hours and killed in the way these people were killed, I don’t think there’d be a brick on a brick in Gaza, or anywhere else.

They’d carpet bomb them, immediately, immediately. So, the answer’s yes. I think I don’t have to make that case. I don’t feel like I have to feel like to make that that Israel’s the most moral army in the world, because I said before, it is that type of low bar.

It’s important that we act in a moral way. We don’t have to go broadcasting it to the whole world.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you ever question the IDF’s conduct in this war?

Michael Oren: Sure.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more about that?

Michael Oren: No, sometimes I have to, you know, I I’ll I’ll have to defend something that happened in this war.

And the IDF has made some terrible mistakes, in bombing and bombing certain civilian areas and bombing health personnel, ambulances. The IDF has not always given convincing answers, and some of the answers have proven to be inaccurate. So, the answer’s yes. And those are the type of mistakes and we have to defend those mistakes and it’s not easy.

Now, I understand, I’ve been in war. I have a big advantage, having been in not just one war, but several wars. And I know that war is total confusion. And I know war, especially with soldiers who are exhausted, you shoot first and you ask questions later.

You do, you want to live. But having said that, and and as I said earlier, the the war in Gaza is of a complexity that is really unmatched in certainly in modern military history. I don’t know anything like it. Having said that, we still make mistakes.

And Israel is a heroic country, but it’s it’s a flawed hero country. We are we are very much like our our forefathers and mothers in the Bible, they who are who are flawed heroes.

Sruli Fruchter: What what do you think most people who aren’t familiar or don’t have the same experience as you with history, with military history specifically, serving in the military, misunderstand about this war?

Michael Oren: Well I had to deal with many people like that and say, the Biden administration, which almost without exception, I can’t think of anybody that had ever served in the army or had ever served in a war.

Sruli Fruchter: In the Biden administration?

Michael Oren: In the Biden administration, nobody.

And that was hard. I mean, there was a spokesman for the Pentagon, that’s about it. John Kirby. And the fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to be in war, and what a soldier’s experience is, actually had a profound diplomatic, even strategic ramifications.

Sruli Fruchter: How so?

Michael Oren: They just don’t know. So, for example, they, you know, say, why are you bombing this civilian area? Why, you know, why take down these buildings? Because in every single building, we’re finding that that Hamas is using them as sniper posts or for or arsenals. And our, you know, our duty yes is to protect civilians to the best degree we have, but our first our first duty is to protect our own soldiers. And and that was a very hard case to make.

Here’s the hardest case of all, was about humanitarian aid. So I took a a contrarian view. I took a few contrarian views that even at the beginning of this war, I thought that Israel should flood, flood Gaza with humanitarian aid, that we should set up humanitarian aid distribution centers in the Gaza strip, that we should set up hospitals in the Gaza strip. And this was a very unpopular position in the State of Israel.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, I’m sure.

Michael Oren: Very unpopular. I’d say it on TV and people would jump on me. I’m used to that.

And the reason, I understood perfectly why. And try to make that case, try to explain this, by the way, to Americans, particularly people in the previous administration, by saying, hello, wait a minute, in World War II, did the United States feel it had to like feed the Germans or feed the Japanese? And would they would they be feeding the Germans and the Japanese in occupied areas where the Germans and the Japanese, where the Nazis and the Imperial Japanese army were taking 60% of the aid and and feeding their troops and using that that the excess money to buy arms to kill your soldiers? Would you do that? And have the Palestinians in any way given us access, the slightest access, for the Red Cross even, to our hostages? And the distinction between Palestinian civilians and Hamas is one which many Israelis simply don’t believe. I mean, in the world, the assumption is that Hamas dropped out of Mars or somewhere into into Gaza and has no connection whatsoever to Palestinian society. And that all those tens of thousands of people, you know, cheering the the humiliation of our hostages or or keeping the hostages are are somehow, you know, an aberration.

And so this is this is a hostile population. We are at war with a people. We’re at war with a with a state, it’s a Hamas state, but we’re at war with the people. And therefore our moral responsibility is not to feed them.

I on the contrary said, no, we have to do this, and we have to do this for one major reason: to give the IDF time and space to fight. Because without offering that humanitarian aid, we will we will not have the international legitimacy we need to continue. And look what’s happened. Every time we’ve tried to stop the aid, the international community comes down on us so, so hard that the Israeli government, even though it’s adamantly opposed to giving that aid, buckles.

It just buckled again, by the way. It just buckled again.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah.

Michael Oren: Because it’s that.

So we we could have preempted, I think, some of that dilemma by doing this. And we would have controlled the aid in which in ways that it wouldn’t have gotten to the hands of Hamas. But that’s, you know, what they call in good Hebrew, Monday morning quarterback. quarterbacking.

And you can’t do that. But it’s one of these issues you’re going to debate. But what I hear over and over again from our critics, particularly among young people in the United States, is the TikTok images of starving Palestinian children.

Sruli Fruchter: If you are making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

Michael Oren: I make it all the time and I begin with this: We’re not fighting our war.

We’re fighting your war. We’re fighting a war for for our civilization against a civilization that rejects everything which we cherish and stand for. That over the course of this war, upwards of 400,000 Israelis have left their homes, left their families, picked up guns, gone off to fight, knowing full well that they may come home irreparably altered or not come home at all for hundreds of days. That 400,000 Israelis is the equivalent in the United States of about 23 million Americans.

That’s about 7 million Americans more than fought in all of World War II. You don’t find a country in the world like this, because no one in Belgium is willing to go out and pick up a gun to fight for Belgium today. We’re the one country in the world that’s willing to stand up and fight for Western civilization. And that, yes, there have been mistakes in this war, there are mistakes in every war.

We are a country, you know, a we’re a heroic country, but a flawed heroic country. We’re we’re a country of human beings. And there’s no there actually is no country on earth like this country. Now, the flip side of that, and I use this with very hostile interviews.

This is with the Irish radio the other day. was to say, they’re saying, well, you are committing genocide, you are starving Palestinians. And and beside taking apart the genocide argument and the starvation argument, you say, why are you accusing Israel of this? You’re accusing Israel is because you must believe at some level that the Jewish people are inherently evil. That we wake up in the morning and want nothing better than to kill Palestinian children, nothing better than to starve Palestinian civilians.

And when you say things like this, to me, I hear the echoes of the 11th, 12th and 13th century, and that nothing has changed in Ireland, nothing has changed in Europe. And by the way, that’s that’s not a propaganda line, that’s absolutely true. I would say 95% of the of the anti-Israel press treatment we receive has anti-semitic resonances that go back centuries. It’s we enjoy killing children.

You never hear the Pales, every time you hear the 56 or 57,000, just heard it this morning again, quote from Hamas that is picked up by the Western press, they always say the majority of them are children. Majority of them are women and children. Jews kill children. You know, that’s not that there’s nothing new.

We kill healthcare, we hear health workers, medical workers. We kill journalists. We kill journalists because obviously if we kill journalists, then then then bad, we’re not going to get any more bad press. That’s why we kill journalists, right? But that’s ob that’s a stupid answer because we keep on getting more, the more journalists we kill by accident, the worse press we get.

So the only reason we must be killing journalists is because we’re inherently evil. And the belief that Jews are inherently satanic is hardwired into Western civilization. On the anniversary of October 7th, the first anniversary, I was interviewed by NBC, by a young woman, wasn’t Jewish. And she started off the questioning the following, she says, isn’t it true that when the Israeli army went into Gaza, it went into Gaza to to take revenge, to exact revenge on the Palestinians.

I said, no, I think the Israeli army went into Gaza to release the hostages, to defend their homes. But isn’t it really about revenge? she went on, like again and again. Isn’t this all about vengeance, vengeance? And I’m having this interview and suddenly I realize I’m dealing with an anti-Semite. She didn’t think of herself as an anti-Semite.

But why was the line of questioning inherently anti-Semitic? Because according to classic Christian thinking, Jesus is the God of love, and the God of Israel is the God of vengeance. So when Jews go to defend themselves, they can’t be legitimately defending their homes or even trying to release hostages. They have to be doing it to take vengeance. You know, exhibit A, the Merchant of, the Merchant of Venice, which is all about Jewish vengeance.

That’s what it’s about. It’s hardwired.

Sruli Fruchter: Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army, even in the context of this war, can that be considered a valid form of love and patriotism?

Michael Oren: Sure. I do it every day.

I love this country, I say in Hebrew, ad ke’ev. Until it hurts.

Sruli Fruchter: So, so on that note, I’m curious.

Michael Oren: Yes.

You’ve heard my criticism today. I’ve given you my criticism, sure.

Sruli Fruchter: So I’m curious, what do you think is the most legitimate criticism that’s leveled against Israel today?

Michael Oren: Hmm, let me think about it, because there are all different types. Um.

Sruli Fruchter: Pull out a list.

Michael Oren: The most legitimate criticism is that the government doesn’t make its case. Neither to the world, nor to the nor to the people of Israel. So I I I began this talk by saying, by expressing my opinion about the way the prime minister may see the situation.

In the ways that other people may not see the situation, because he has that 360 degree view. But when was the last time you heard the prime minister actually come out and make that case?

Sruli Fruchter: Why do you think he’s not?

Michael Oren: I just don’t know. He’s he’s a very good communicator. But it’s not just him, the entire government doesn’t do it.

When was the last time you heard? When was the last time you heard, you know, the prime minister, I think, I think admirably visited Kfar Aza for the first time or Nir Oz for the first time like last week. Why did that take nearly two years?

Sruli Fruchter: So as someone who’s served in the Knesset and served as in Ron Dermer’s position before him.

Michael Oren: No one’s ever served in Ron Dermer’s position. Ron Dermer’s position is very unique.

It’s not as ambassador, yes.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, when he was ambassador, ambassador, correct. I mean I’m I’m curious, what would be your best guess about why there isn’t that communication?

Michael Oren: There are several reasons. One is it’s very difficult for the government of Israel to adopt a unified position.

So when I’d be in Washington, the foreign minister would come and say, we will never redivide Jerusalem. And then another minister would come and say, oh, we’re ready to redivide Jerusalem. And people in Washington say, well what’s your policy? And my, I’d have to give a lame answer and say my policy is the position of the government of Israel. The ministers can say all sorts of things.

So it’s difficult to get a unified position. That’s one. Two, there is a a tremendous amount of contempt, hardwired into Zionist thinking, for world opinion. And this goes back to an old Ben-Gurionism that it’s not important what the the non-Jews think, it’s what the what the Jews do.

And you’d be surprised how how deep-seated that thinking is here. The, finally, there’s just despair, especially among young Israelis. No matter what we say, what we do, people are going to hate us anyway. So you have that.

So there are many reasons.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Michael Oren: No. Why? First of all, it depends how you define peace.

Sruli Fruchter: How do you define peace?

Michael Oren: I, a peace between the United States and Canada.

Sometimes that’s a little rocky right now, too. Or Germany and France. That’s a very, that’s a very different type of peace. Or even the peace we have with the United Arab Emirates or the other signatories to the Abraham Accords.

I think we can manage our relationships much, much better. I think that we can have peaceful relationships with different modes of Palestinian organization. For example, right now, I just wrote an article for the Wall Street Journal in support of Mordechai Kedar’s plan for for emirates, which I think is something that goes way back. I’ve been supporting an idea like that, believe it or not, since the early 80s.

And so is that with the Palestinian people? No, but it’s with a certain group of Palestinians. For example, in Mordechai Kedar’s thinking, it would be a sort of an emirates of of Hebron and emirates of of Nablus and etc, etc. We could have much, much better relationships.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think is holding that back now? Meaning, you’ve been in the Israeli political sphere for decades. Right.

You’re still involved in this work now, in a different capacity, but in the same spirit. What do you think is holding that back from materializing?

Michael Oren: So, having been involved in the peace process for many years, I participated in the last round of talks with the Palestinians and been in touch with, you know, Palestinian interlocutors for many years. And over these course these peace talks, we were talking about borders, and you’re talking about territory, and you’re talking about settlements, and you’re talking about Jerusalem and security arrangements. And there was one line that a a chief Palestinian negotiator said to me back in, oh boy, it’s got to be like 2011, 2010, that that has made me realize that I understood nothing about this conflict.

That you can be in a university for 20 years, you can be a professor, you can read, you know, hundreds of books about the conflict, and all of a sudden you realize you understand nothing. And what he said was the following. He said, you, Israelis, want us to recognize you as the Jewish state. But don’t you understand that by doing that, you’re asking us to negate our own identity? Now, you should know that the demand for recognition of Israel as the Jewish state is one that has been a multi-partisan.

Ehud Barak demanded it, Tzipi Livni demanded it, Netanyahu certainly, but also Barack Obama and Biden, because it’s the it’s actually the key to the whole thing. Because we recognize the existence of a Palestinian people. We actually recognize the existence of a Palestinian people with the right to self-determination. That’s in the Oslo Accords.

But you will not find any Palestinian leader ever, ever, ever who will recognize that there actually is a Jewish people, a Jewish people with an indigenous history here. Everything we dig up out of the ground is all artificial, it’s fake, okay? It’s fabricated, they call it fabricated history. And the Jews, the Jewish people have the right of self-determination. So even if you had a two-state solution, one state, the Palestinian state would be legitimate, and the second state, the Israeli state, the Jewish state would be would be transitory.

And you have immediately irredentist. So it was a key, it was the key to the peace process. Obama actually understood this after a time. It took a while.

And so here is, this was Saeb Erekat saying, you know, you want us to recognize you as the Jewish state, don’t you understand that means you’re asking us to negate our identity? And all of a sudden, you know, as they say in Hebrew, the asimon fell, the the lightbulb went off. And I realized that I understood nothing. Why? Because we are Jews and Israelis. We wake up in the morning, we’re Jews and Israelis because we have this thousands and thousands of years of history, because we have the Tanach, because we have many, many sources of Jewish identity.

They wake up in the morning and they’re Palestinians because they’re not us. And that by accepting us, they cease to be them.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: Now, think about that.

Now, how do you solve a problem like that? And when I listen to smart Palestinians, and there are some smart Palestinians thinking out there, they understand this, that that Palestinian, instead of that the main goal of Palestinian leadership in the future should be to wean the Palestinian people of victimhood and addiction, addiction to victimhood, and to free their identity of victimhood. It’s one of the great achievements of Zionism. I’ve often been an opponent of the tradition of bringing foreign leaders to this country and bringing them immediately to Yad Vashem. That shouldn’t be our message.

Bring them to the Knesset.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: Bring them to a kindergarten in Jerusalem, but don’t bring them to Yad Vashem because that’s not what we’re about. We’re not about victimhood, but the Palestinians are.

They are. And it’s one of the great conundrums we face in Gaza. Because our definition of victory would be to vanquish Hamas, destroy, say, Gaza. But their definition of victory would be to actually acquire more identity as victims.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: So the more we win, the more they win. And we’re in this sort of this pathological relationship that we have to break. And the way to break it is to wean them of victimhood.

Sruli Fruchter: So, what do you think should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the war?

Michael Oren: I don’t know. I know just basic, I won’t go into detail. The Gaza Strip has to be demilitarized. It cannot threaten the state of Israel again.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: It has to be rid of Hamas.

Sruli Fruchter: And I actually not to interrupt you, but I remember in 2014 you had actually insisted that Israel continue fighting Hamas and not end the war when they did. And I’m curious what that’s like within this question, what it’s like today.

Michael Oren: There were no hostages. That’s the big difference. I’m a big advocate of giving war a chance. We get peace by beating the enemies, not by retreating.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm. I know I sidetracked you. You were saying about the …

Michael Oren: The big difference is the hostages.

That’s the huge difference. And that’s an immensely complicated issue that goes to the core of Israeli identity and our resilience.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: But let’s take that later.

But right now, has to be demilitarized, de-Hamasified, however you want to say it. I also gave an interview to the Wall Street Journal a year ago, last December, that’s about a month or two after October 7th, where I said that we should do to for Hamas what we did to the with the PLO in Beirut in 1982. We should load them on boats and send them away.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: And I still think that. And they’re still talking about that. But if anybody thinks that just by building hotels that Hamas, that Gaza will be pacified, they’re making the same mistake of those people who think that Hamas fell into Gaza out of Mars.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: Hamas is a product of Israeli of Palestinian society. Hamas is a product of a society that begins educating their children before they can walk that the most sacred thing they can do is take off a Jew’s head. I went through, I deal with the Hamas education system. By the way, it’s not that all much different than the PA system, but okay.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: And nothing’s going to change in Gaza until that until the education system changes. And that’s a process of 20, 30 years. That doesn’t that’s not going to happen overnight.

And so if we’re going to be seriously thinking about living in peace in some way, side side with Gaza, you’ve got to start a process that is going to take a long time.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm. Do you think Israel’s properly handling the Iranian threat?

Michael Oren: I think the question is whether Israel can properly handle the Iranian threat.

Sruli Fruchter: Uh-huh.

Say more about that.

Michael Oren: And yes, here. Well, first of all, we need a green light from the United States. And the Prime Minister has just been in Washington.

And I would view that that would be his primary goal, even more than Gaza, was to get that green light, because it wasn’t certain that we had the green light. The last day of the the first day of the ceasefire, it was President Trump who recalled our warplanes, okay, and said that Prime Minister Netanyahu was out of his mind with an expletive before the word mind. And so it’s not clear whether the United States would give us that green light. Maybe it’s clearer now.

And then we also learned that we learned the limits of Israeli society, because I don’t know how many more nights we could have gone on sustaining the type of missile damage that we were sustained.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: And these are very difficult questions that we have to ask ourselves. And so the question is whether Israel handled it right or ended it too soon is not is not really the question.

The real question is could Israel have done it.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: And …

Sruli Fruchter: What would that have looked like then to do it properly?

Michael Oren: Oh, we just would have kept on bombing them.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: And and the United States too. You know, the president of of the United States called for unconditional surrender.

Sruli Fruchter: Mm-hmm.

Michael Oren: No president has ever made a call like that since Roosevelt at the Casablanca conference in 1943. There, I’m a military historian. But Roosevelt and Churchill and later Stalin followed up that that pledge for unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany and Japan, by making sure that they surrendered unconditionally. Okay? And here the Iranians haven’t surrendered and they certainly haven’t surrendered unconditionally.

And to do that, you had to keep on applying very harsh military pressure. And very much in contrast to the United States and the allies in World War II, the pilots that were carrying out that bombing faced almost virtually no dangers. There may be technical failures, but our pilots conducted hundreds and hundreds of sorties over distances of 2,000 kilometers plus and didn’t lose a single airplane. Didn’t lose a single soldier in this war.

It’s pretty amazing. Talk about what you’re going to study at West Point. So you could bomb with impunity, you could keep on bombing. But the constraints were one on our side, how much damage was civilian damage was Israeli society willing to sustain.

And I was feeling toward the end of the war that we were reaching our limit, because these these ballistic missiles, not only was our our anti-missile defense proving less efficacious every night, but these missiles took down not just a building, they took down a neighborhood. And you know, the impact on the economy, on the psychology, on kids not going to school, no one’s going to work, all had a tremendous price. But in the United States, the constraints were such that close to 90% of the American people were against a continuous American military involvement in the Middle East. And even President Trump could not ignore that entirely.

Sruli Fruchter: Is Trump good for Israel?

Michael Oren: Uh, certainly empirically, is the the most pro-Israel president we’ve had. And you know, I don’t go through the whole list of his great achievements. Your listeners probably know them. Um, right now he is the first president in American history to join with the state of Israel in an in offensive operations.

There have been many cases of the United States joining with Israel in defensive operations, but never in offensive operations. And he’s given us so far a green light in in Gaza, certainly in Lebanon. That was not the case in the previous administration. Uh and would not have been the the case if that administration had won re-election.

Um, let’s be honest, be very different.

Sruli Fruchter: If the Harris Biden administration, or I guess the Harris administration had won the elections, were you concerned for what that would mean for Israel?

Michael Oren: Certainly. What were you concerned about? No, I just think that that that the the type of constraints we’re under in the first Biden administration would would only grow in the second. And that is uh you know, putting pressure on us to say for not, remember this is an administration that didn’t want us to go into Rafah, didn’t want us to go into Lebanon.

Certainly didn’t want us to to you know, to fight Lebanon to Iran. Uh, and was willing to take steps such as withholding um crucial forms of of ammunition. Um, so there was that precedent. Just I’ll I’ll add parenthetically that in 2016, I was the only member of the Israeli government to oppose Obama’s aid package.

Here I am Mr. America and I oppose American aid. It’s a long story. There’s an article I wrote in Tablet back in uh 2021 that sets out the argument. There are many reasons why I oppose aid.

But one of the biggest reasons was that during the 2014 war with Gaza, President Obama withheld forms of ammunition with the claim that we were killing too many Palestinians. And I said, uh oh, if we’re ever in a bigger war, this is going to become a huge problem. And we have to be ammunition independent, certainly with tank and artillery ammunition. Turns out, what can I say? I was right.

And I think now the majority of Israelis agree with me that we have to have that independence. Um I’m not sure the American continued aiding us in various ways. I I wanted a relationship of of partnership uh in areas that were mutually beneficial to our security, cyber, laser, intelligence. And it doesn’t mean the United States can’t aid us in critical ways during during times of crisis as President Biden did very generously with billions of dollars.

But um, how did we get on this subject? I can’t even remember. But it was it started off being parenthetically and then …

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, we’re speaking about the Harris administration.

Michael Oren: Yeah.

So that uh, so here again, it turns out that they were willing to withhold ammunition because quote unquote we’re killing too many Palestinians. Or as you know, Tony Blinken would say over and over again, entirely too many Palestinians have been killed, which is a a very strange locution because it assumes that there’s some number that would have been okay. Uh seven was too much, but three would have been okay. There’s no end to that.

There’s no way of getting out of that that moral bind of killing too many Palestinians. Um we’re always going to lose that argument.

Sruli Fruchter: I I want to shift away from now talking more about the war and the diplomatic setting. What do you think the world misunderstands about Israelis?

Michael Oren: You’re going to find this very funny.

Sruli Fruchter: I’m ready to laugh.

Michael Oren: All right. Misunderstands, the world misunderstands how sweet Israelis are. Israelis are unbearably sweet and hospitable and passionate.

I was thinking, you may be too young to know this term, but if you were a sailor serving in war, you’d get shore leave and you’d go a little crazy on shore leave. I this is a society on shore leave. Like in between bouts of rocket fire, like horrendous rocket fire, we go out and five minutes later after the ceasefire, we’re out on the beach. And they’re we’re celebrating and eating well and and being with family.

We’re we’re a society on on on shore leave. And people don’t understand that spirit either. They don’t understand the the truly indomitable spirit of the people of Israel. They don’t understand the the generosity and philanthropy of the people of Israel.

In this war, I’m going to go back to the war, 80% of the Israeli population went out and volunteered in some way. I’m writing a book about the war. On the on the first day of the war, October 7th, 2023, a call went out from, you know, Magen David Adom, that we need blood. Within eight hours, they had more blood than they had room to to to to store.

That type of of. It is, I think I’ve made the case we are a country of of indescribable courage, courage, individual courage. I see it again and again. This is a …

We’re also an impossible place. We argue, we yell, and in Knesset, if the if our seats weren’t screwed into the floor, we’d throw it at one another. And we can be pushy and we can honk and, you know, and the worst thing you can call an Israeli is a frayer, right? And God forbid you call anybody a frayer. But people don’t understand this about Israelis, that this is a, it’s truly a remarkable society.

Sruli Fruchter: Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum? And do you have any friends on the quote unquote other side?

Michael Oren: Yeah, in Knesset, almost all my friends were on the other side. And remained so.

Sruli Fruchter: So well, let’s start, where do you identify?

Michael Oren: My best friend is is anyways, our best friends were on the other side.

Sruli Fruchter: But where do you identify politically and religiously?

Michael Oren: Well, I think before I said I was a right, right of center on certainly on security issues, left of center on social issues.

And I’m Jewish before I’m Israeli. That’s the first question. I would always ask my staff, whether in Washington or in the Knesset, what are you first, Jewish or Israeli? And the responses were very interesting. Usually the secular people are more Israeli first than Jewish.

I asked the same question of diaspora Jews. I was in a while ago, I was in France dealing with French Jewish youth. And I asked, okay, who’s French first and Jewish second? Who’s Jewish first and French second? And it was interesting how it broke down. It broke down very, very clearly.

The people from North African background were Jewish first. The people from sort of quote unquote French background, European background were were French first.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. And now for our last question.

Michael Oren: That’s that’s it? I’m having a good time.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, we’re just going to, I mean, now we’ll roll another 18.

Michael Oren: Yeah.

Sruli Fruchter: Our last question.

Do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish people?

Michael Oren: I think we’re living through again, let’s go back earlier. I said we’re now living through through historical times, we’re living through biblical times. And we have an interesting national epic. Because most national epics are stories of great heroism and and triumph.

And yes, we have a lot of heroism in our Bible, but ultimately our national epic is an epic of defeat and exile, which is unusual for a national for a national book. Our book tells us how we screwed up, right? And, ultimately. And so, yes, I have those fears. I look around, I see what’s happening in the Jewish world.

I see the rising anti-semitism. I deal a lot with what’s called track two diplomacy. It’s sort of an unofficial foreign ministry I run. And I visit Jewish communities around the world and I I see Jewish communities that a few years ago were immensely secure and now believe they have no future.

Good example would be Australia. I see rising anti-semitism in the United States and and don’t know about the future even of American Jewry. And in this country, I see the greatest threats we face are not external, they’re internal. Whether we can bridge these gaps between religious, secular, right wing, left wing, ethnic divisions which remain, and maintain our democracy.

And all of this. And yet, I have three perspectives that give me, I think, unassailable hope. Okay. One perspective is as an historian, just an historian, okay.

I look at what this country was like on May 4th, 1948. It had nothing. It was 600,000 Jews in this country, about the about the size of Boston. Nothing.

I worked for years with Shimon Peres. He told me he found a note in Ben-Gurion’s drawer on a desk on May 14th, 1948. It was from the Haganah saying that they had enough bullets to fight for one week. Okay.

That kind of thing. And no allies, no natural resources, and we turned around and created this. We created a country which by any international standard is one of the world’s most successful nation states, right? I can go on and on just for an hour telling you why. you know, the water that comes out of your tap is better than anything you get in a bottle.

How many countries in the world have that? A national health service, the army, anything, okay? One of the few countries by the way to never have known a second of non-democratic governance. It’s a very short list. Really very short list. Uh, and we’re the only country on that list that’s never known a second of peace, which is even more impressive.

And we did this. So that’s one perspective. It’s a historical perspective. And there’s a personal perspective.

I’m living here a long time. The country I came to was a poor agrarian backwater. Our our major export item was orange juice. We were isolated in the world.

We had no relations with China, no relations with India, you know. You can go to the army and get on a backpack to India, but you weren’t coming back. And no relations with what was known as the the Soviet bloc, was 12 12 countries, Soviet Union, 3 million Jews trapped behind the Iron curtain, no peace with Jordan, no peace with Egypt, no peace really with the Abraham Accord countries, no peace with Africa. We didn’t have relations with Africa.

A little bit here and there with South Africa, but we had a nice relationship with the United States sometimes, but not a strategic alliance with the United States. So in my lifetime, the time I’ve been here, that perspective is, um, look, look what’s look what look what look where we’ve come. All of that, the transformation here, literally unbelievable. If you had told me back when I moved here that someday we’d have peace with Egypt and Jordan, with Bahrain and UAE, that someday we’d be a high-tech powerhouse, that we would have with the United States one of, if not the deepest bilateral strategic alliances which the United States has ever had with any country.

I’d say you’re crazy. I think you’re completely, utterly nuts. Nuts. So there’s that perspective.

And then the third perspective, which is probably the most important perspective, is that, um, I believe, I’m a believer in Netzach Yisrael. And I believe we’re not alone in this enterprise. And that’s the most powerful source of my, my optimism. That our history is not accidental, our presence here is not accidental.

In fact, it’s just the opposite of accidental. It is it is rife with meaning, pregnant with meaning. And that, uh, and I take that with me. You know, last night, I’m, um, the president of a of another NGO that supports the the border police and particularly bereaved families of the border police.

Last night I went to a a shiva for a 20-year-old soldier who was also a volunteer with our organization. And you sit there and you you daven Aravit and you sit with all these people who are just from Israel, just, you know, from a a moshav in central Israel. Most of them from, you know, working class, mostly Mizrachi background. And the the the pain is unbearable.

It’s literally unbearable. And if you don’t have that type of belief, and the belief that brought all these people together to daven in that way, then you you would have a very hard time getting over it. That belief, even among secular Israelis, very secular Israelis, that gets them to pick up that gun and go out and fight. And you you got to see this to believe it.

And it’s it’s that belief which is absent in so many of these Western countries that aren’t, don’t feel that their countries are worth fighting for. You see it in the family sizes here. Because we are the only industrialized country that has a positive growth rate at this point. And it’s not just positive, it’s very positive.

You go to Park Hayarkon on Shabbos and the kids are falling out of trees, okay? And who has kids today? You have kids today because you believe, because you believe in a future, because you believe at some very visceral, almost subliminal level that all of this has meaning. And you want to impart that to future generations, even though you know when your kid’s born that there’s a good chance someday that kid’s going to be wearing a helmet.

Sruli Fruchter: Wow. Well, Rabbi Oren, thank you so much for your time and thank you for answering my 18 questions.

How was this for you?

Michael Oren: Great, great, great.

Sruli Fruchter: Thank you so much for tuning into the final interview for 18 questions for 40 Israeli thinkers. We still have more coming out from this podcast over the next couple of weeks, so stay tuned for that. And as always, thank you to our friends Gilad Brownstein and Josh Weinberg, who oversaw and edited the audio and video of this podcast respectively, and to everyone on our team who has helped make this possible.

And again, we want to hear from you. If you have questions, ideas, or comments, reach out to us at info@18Forty.org. And so until next time, I’m your host Sruli Fruchter, and keep questioning and keep thinking.

This transcript was produced by Sofer.AI.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

Recommended Articles

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

Ki Tisa: The Limits of Seeing God’s Face

We spend our lives searching for clarity. Parshat Ki Tisa suggests that the most meaningful encounters may happen precisely where clarity ends.

Essays

The American Yeshiva World: A Reading Guide